CEO of an enterprise company: it takes forever to close deals and I have to design for the corporate check-signer and not for end-users! I wish I could iterate and get customers more quickly!

CEO of a consumer company: Google and Facebook ads are so expensive, and my organic traffic got squashed by that new <insert platform here> algorithm change! And then they cloned my product! I wish I had more predictability via contracts and ability to forecast my revenue!

Most companies either sell to enterprises (B2B) or consumers (B2C), although many consumer product companies have a B2B advertising revenue model (“if you’re not the customer, you’re the product”).

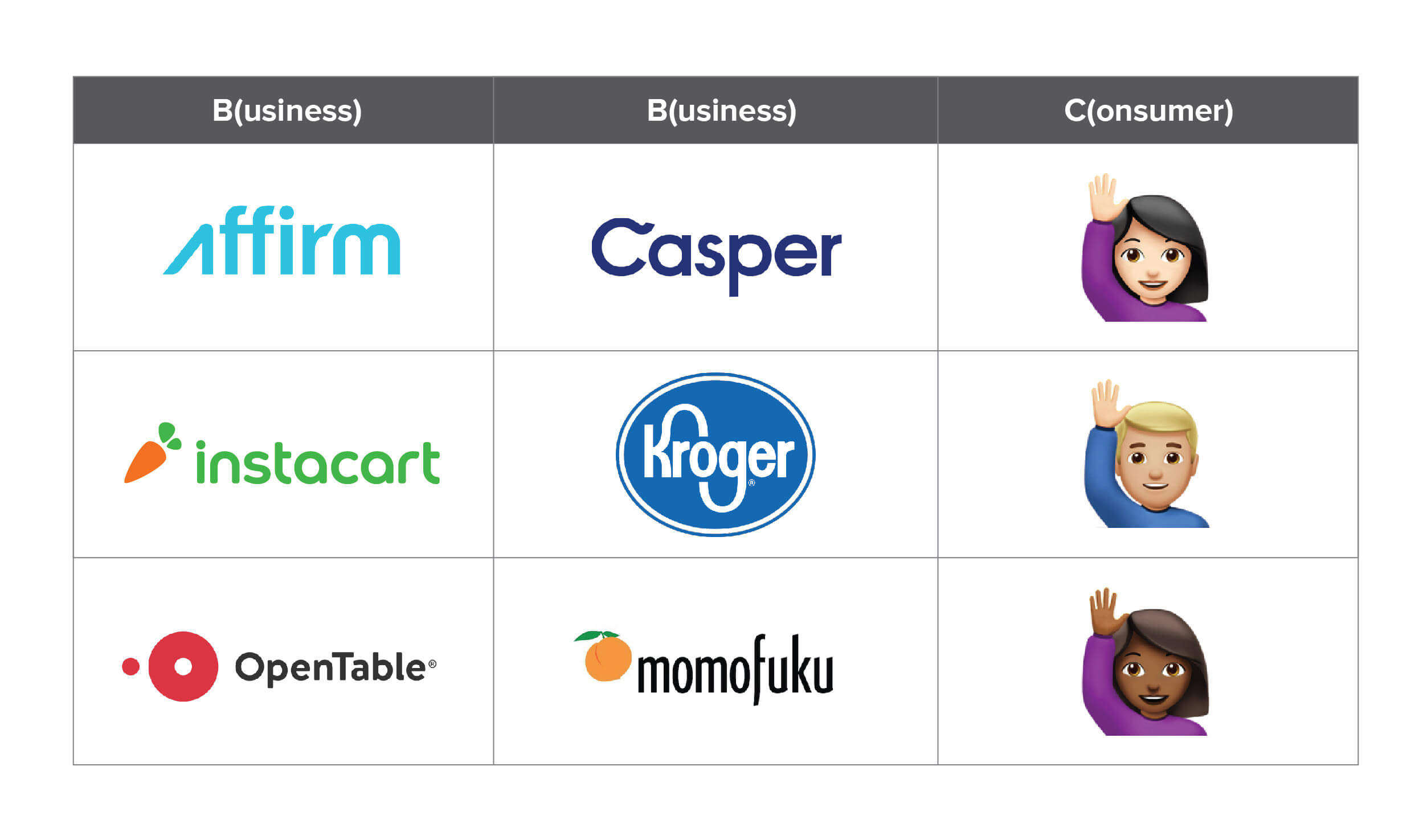

There’s a third model, though, which is commonly called B2B2C. It’s where your company sells a product/service to a business, gaining customers and/or data from that business that you get to keep and use. And where, most importantly, that group of customers becomes untethered from the middle B—at some point, they recognize that YOU (the first B!) are the product they use. Think Affirm in consumer lending, Instacart for grocery delivery, OpenTable for restaurant bookings, or even how Google started off—co-branded search for Yahoo and AOL. In each case, a well-structured set of business deals led to lots of downstream consumers with no per-customer acquisition cost. “Channel partnerships” and reselling—where a business with an existing channel (route to customers) agrees to sell another company’s products—underpin all of business but are typically not B2B2C. When you go to the supermarket, you buy things from Whole Foods not manufactured by Whole Foods, but from manufacturers for whom Whole Foods is a distribution channel. When you book a Hilton hotel on Kayak or Expedia or via American Express, those all serve as distribution channels for Hilton, and Hilton owns the customer.

“Channel partnerships” and reselling—where a business with an existing channel (route to customers) agrees to sell another company’s products—underpin all of business but are typically not B2B2C. When you go to the supermarket, you buy things from Whole Foods not manufactured by Whole Foods, but from manufacturers for whom Whole Foods is a distribution channel. When you book a Hilton hotel on Kayak or Expedia or via American Express, those all serve as distribution channels for Hilton, and Hilton owns the customer.

It can be complex to differentiate between a “channel partnership” and a B2B2C arrangement, but I’ll try to define it this way:

Business A needs to solve a problem (not stock an additional “product”) for its consumers—often a “horizontal” service across its myriad products.

Business B offers a solution to Business A’s problem.

By virtue of solving this problem, Business B ends up clearly (co)owning the customer of Business A, albeit with a shifting power dynamic.

[for clarity, mapping these to B2B2C as a sales strategy, Business B is you, selling a solution to Business A, yielding customers—B2B2C]

For example, take ratings and reviews. When Amazon started rolling out reviews, many online retailers wanted to offer the same functionality to their customers, turning to PowerReviews or BazaarVoice.

A “white label” solution of PowerReviews or BazaarVoice not showing its brand—instead just doing the backend software and hosting customer reviews and customer accounts—is just normal B2B software.

But a solution where each consumer reviewer on Sears.com knows he or she is creating an account with BazaarVoice for a review that shows up on Sears and can use that account to leave reviews on other retailers as well, and browse reviews across all retailers on BazaarVoice.com… this would be B2B2C, assuming that this isn’t an accident, but that BazaarVoice seeks to profit by building a large consumer network.

It’s a tricky proposition, because most Business As would prefer a white label piece of software, and are justifiably paranoid about Business B doing “other” things with A’s most valuable asset: their customers. But most smart entrepreneurs recognize the pricing power, product improvements, and defensive moats that come with a multi-tenant solution where the customers of every Business A can be blended together into a unified network.

With that in mind, here are some thoughts, both in terms of timing your network (subsuming your independent wishes to the wishes of the early “Business A” adopters) and when a B2B2C solution truly makes sense.

B2B2C is easiest to sell when Business A does NOT want to be in the business you are offering, largely for the customer support/operations complication. This could be for “plausible deniability” (“sorry, that’s our partner”) or just to simplify operations—comparative advantage. Examples might include lending (don’t want to bother customers with collections); delivery (economies of scale); or regulatory (don’t want to train or deal with compliance). In other words, Business A wants a different brand involved.

Don’t tickle the bear—optimize for early clients first, as keeping track of “what can I do with differently-acquired groups of customers” is unwieldy. Telling an early partner “I’m planning on getting your customers from you, then sending those customers to your competitor” or “I’m planning on getting data from you and using it to make models and sell them to your competitors” is a surefire way of losing a prospective A. Even if this is your long-term plan, (1) hopefully there is a set of complementary, non-competitive Business As you sign up, and (2) it might never come to fruition. Don’t over-optimize your legal contracts for a situation that might not happen for 5 years—or ever. It does, however, make sense to explain to your clients why you might need consolidated customer data/ownership/contact rights (for customer support, for preventing abuse/fraud, etc).

Give > Get: a logical time to “flex” end-customer ownership is when you are able to contribute more to Business A than you receive from Business A. It can also make sense to “pivot” a white label B2B product into a B2B2C product once you can show each incremental business that you are giving them vastly more than you are taking.

The “exhaust” of a B2B2C business is either customers or their data. It’s essential that end customers identify as customers of your Business B if you have a plan to count them as yours (and the same applies to data). Records in a Salesforce.com business’s database clearly don’t identify as having a relationship with Salesforce. And just having something in your Terms of Service giving you rights doesn’t mean that it will make sense to customers or Business A.

A signed contract is just the beginning of the sale. One of the reasons for failure in the early stages of B2B2C is that Business A doesn’t sufficiently promote your product. A classic example of this is employee benefits. Signing a large employer (who provides a path to its many employees) is step 1, but is arguably the least important step. What happens next? Your Business B is reliant on Business A promoting this to all employees. Does it get promoted once? Every week? Every day? In the HRIS? Do you have the right to contact employee leads who haven’t yet bought? Will that make sense to employees or to Business A? This is arguably the most crucial reason why B2B2C partnerships often do not work—there are two layers of customer success, one for the Business A “client” and one for the end customers you hope to attract.

Done right, B2B2C can be one of the most effective ways of acquiring customers and constructing a powerful moat. Anyone can acquire customers on Google or Facebook, but B2B2C channels are generally proprietary, and often yield network effects (network improvements based on acquired consumers/data) that prevent your economics from deteriorating. B2B2C models aren’t right for every business idea, but if they work for the idea/service you are building, it’s crucial to spend time on repeatability of implementation, post-signing success, and navigating the complex path of customer ownership—and then this model can really shine.