Editor’s Note: This testimony was delivered by a16z managing partner (and former chairman of the board of the National Venture Capital Association) Scott Kupor to the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, & Urban Affairs as part of their hearings in January 2018 on CFIUS reform — i.e., the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) of 2017. You can see some of his other writing on this topic here. Kupor is also the author of the new book, just out, Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It.

Chairman Crapo, Ranking Member Brown, thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Senate Banking Committee regarding reforms to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2017 (FIRRMA, S. 2098). My name is Scott Kupor and I serve as Managing Partner of Andreessen Horowitz, a… venture capital firm that has invested in many early-stage technology companies… I am testifying in my capacity as Chair of the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA).

As detailed below, the basic business model of venture firms is to raise capital from a diverse set of investors to invest in startups. Some of these investors (which we refer to as limited partners, or LPs) are from abroad, as foreign investors seek returns from venture investing in the same way that U.S. investors have for years. While U.S.-based universities and endowments have been — and continue to be — important limited partners in venture capital funds, increasingly non-U.S. investors are seeking to deploy capital in U.S. venture funds as a means of generating above-market returns. I believe that policymakers should encourage, and not be fearful of, foreign investment into U.S. venture funds.

The U.S. has a very strong entrepreneurial mindset, world-class research universities that help engender forward-thinking research and development, and an incredibly strong talent pool of individuals seeking to build new technology-based businesses. Developing these businesses — the benefits of which will accrue to the U.S. in terms of employment, economic growth, and increases in the overall standard of living — requires risk capital; thus, it is imperative that we retain a robust venture capital financing ecosystem in the U.S. and continue to attract non-U.S. dollars. If we create obstacles to the investment of these dollars in the U.S., they will simply go to other countries. The other countries that receive these dollars may make gains in defense-related technologies, along with other attendant benefits that come along with new company formation.

In fact, to illustrate this, the U.S. venture capital industry represented about 90% of global venture capital dollars in 1990; today, that global market share has been reduced to 54% [source: Pitchbook/NVCA data]. To ensure that we as a country maintain our global technology lead, we should make sure that the U.S. venture capital markets remain open and attractive to non-U.S. players. Other countries are eager to take advantage of any obstacles we place to the free flow of risk capital in the U.S. to further their own attractiveness to global investors.

The U.S. venture capital industry stands ready to work with the Senate Banking Committee and the authors of FIRRMA to ensure the legislation does not produce unintended consequences that may be harmful to new company creation in the United States.

Venture capital and its importance to the U.S. economy

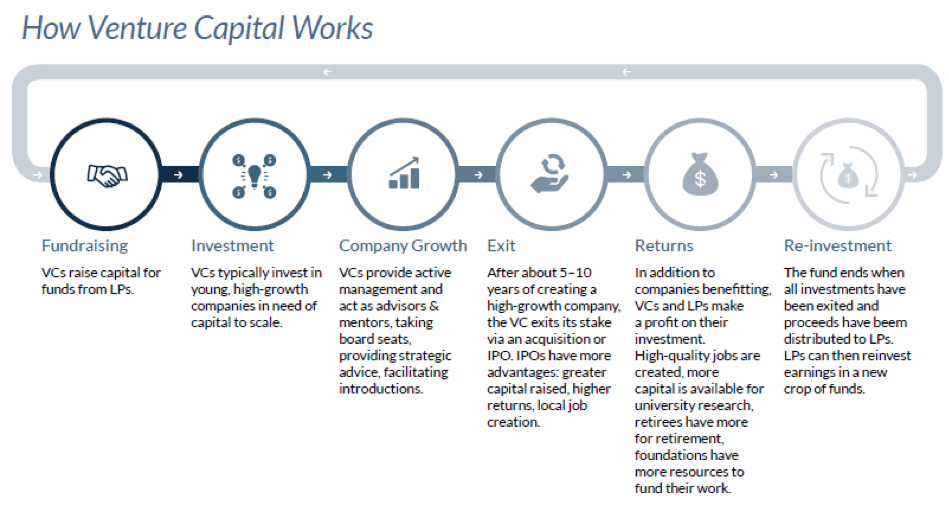

The story of venture capital (VC) is really a subset of the story of entrepreneurship. As venture capitalists, we raise investment funds from a broad range of LPs, such as endowments, foundations, pension plans, family offices, and fund-of-funds. The capital raised from LPs is then invested in great entrepreneurs with breakthrough ideas. Venture capitalists invest anywhere from the very early stage, where the startup has little more than an idea and a couple of people, to growth-stage startups, where there is some revenue coming in and the focus is on effectively scaling the business. Generally, a company leaves the venture ecosystem via an initial public offering (IPO), a merger or acquisition, or bankruptcy.

There is often a misconception that venture capitalists are like other investment fund managers in that they find promising investments and write checks. But writing the check is simply the beginning of our engagement; the hard work begins when we work with startups to help entrepreneurs turn their ideas into successful companies. For example, we often work with our companies to help them identify talented employees and executives to bring into the company or to identify existing companies who can serve as live customer test sites for their products.

The reality is that those who are successful in our field do not just pick winners. We work actively with our investments to help them throughout the company-building lifecycle over a long period of time. We often support our portfolio companies with multiple investment rounds generally spanning five to ten years, or longer. We serve on the boards of many of our portfolio companies, provide strategic advice, open our contact lists, and generally do whatever we can to help our companies succeed. While we hope that all of our companies succeed against huge risks and grow into successful companies, the reality is that the majority fail. As this committee appreciates, entrepreneurship is inherently a risky endeavor but it is absolutely essential to the American economy.

Successful venture-backed companies have had an outsized positive impact on the U.S. economy. According to a 2015 study by Ilya Strebulaev of Stanford University and Will Gornall of the University of British Columbia, 42 percent of all U.S. company IPOs since 1974 were venture-backed. Collectively, those venture-backed companies have invested $115 billion in research and development (R&D), accounting for 85 percent of all R&D spending, and created $4.3 trillion dollars in market capitalization, 63 percent of the total market capitalization of public companies formed since 1974. Specific to the impact on the American workforce, a 2010 study from the Kauffman Foundation found that young startups, most venture-backed, were responsible for almost all the 25 million net jobs created since 1977.

It is quite clear that the American economy is dependent on the economic activity that comes from young firms scaling into successful companies. The rapid hiring, innovative product development, increasing sales and distribution needs, and the downstream effects all serve to push the U.S. economy forward. The American economy needs more of this activity to help deal with many of the challenges we see today. Historically, the United States has done an excellent job encouraging risk-taking and entrepreneurship, but it is imperative that policymakers, entrepreneurs, and VCs work together to encourage entrepreneurship in our country.

Challenges to American leadership

The story of modern venture capital began in the U.S. and, as a country, we have been the predominant funder of most startup ventures. But other countries see the benefits that entrepreneurship has brought to the American economy and are increasingly competing with the U.S.

Increased interest in startups by other countries has caused the share of global venture capital invested in the U.S. to fall from 90 percent to 54 percent in only 20 years [see previous link]. Foreign investment in the U.S. economy is the focus of this hearing, but it is important to note the degree to which startups in other countries are now attracting capital, and how innovation and entrepreneurship has become a global competition. There are undoubtedly justifiable concerns about China trying to procure sensitive technology through U.S. investment, but the reality today is they are building first-rate technology themselves. China attracted $35 billion in venture investment in 2016 and is now the second largest destination in the world for venture capital. In 2016, six out of the ten largest venture deals in the world occurred in China [see previous link]. It is therefore critical that policymakers spend time solidifying our leadership position in entrepreneurship through regulatory changes, more effective startup tax policy, immigration reform, and increased investment in basic research.

Foreign investment in U.S. startups and venture funds is challenging to quantify

Because VC is a form of private capital, tracking exact sources of capital is nearly impossible. LPs, VCs, and startups all keep records of the investments they have made and/or received but are typically not required to publicly report these details. Except for public pension funds or other LPs mandated to do so, LPs generally do not publicly release information on their fund investments. Some VC funds publicly share the total fund size, date, and focus of a recent fundraise via a press release, their websites, or media interviews but rarely publicly disclose who are their LPs. Similarly, a startup may choose to publicly disclose a recent funding round, the amount of capital raised, and/or the participating investors, but the amount each investor contributed is generally not shared. For these reasons, attempts to quantify the dollar amount of 1) foreign investment into U.S. VC funds, or 2) foreign entities direct investment into U.S. VC-backed startups are limited and unreliable.

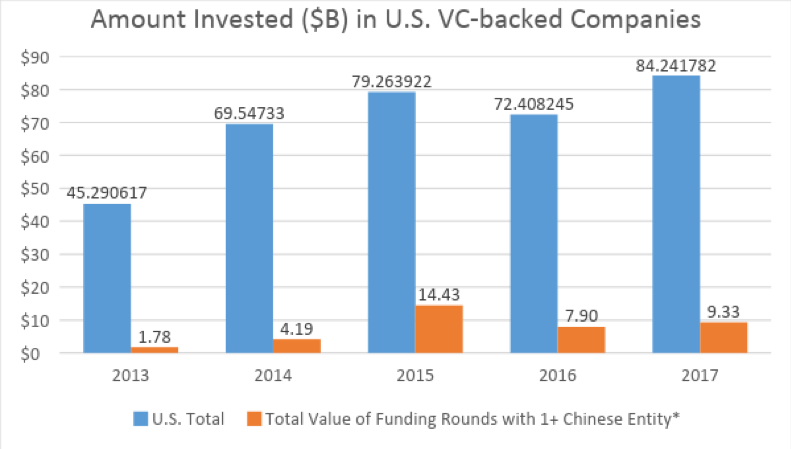

Thus, while we do know that globally LPs committed approximately $142 billion to U.S. VC funds from 2014 to 2017, we do not have precise figures indicating how much of these LP dollars are from Chinese and other foreign LPs. As a practitioner in the venture capital industry and the managing partner of a set of funds that have a diverse set of U.S. and non-U.S. LPs, I do believe that the amount of Chinese LP investment in U.S. venture capital firms is very small. I would estimate that fewer than 5% of total U.S. LP commitments are from Chinese LPs, and, anecdotally, I believe that most of that money is from private family offices or the large Chinese consumer internet players and not from Chinese government-related entities. There is a more robust non-U.S. ecosystem of venture capital LPs in other geographies, e.g., Singapore, Western Europe, and the Middle East.

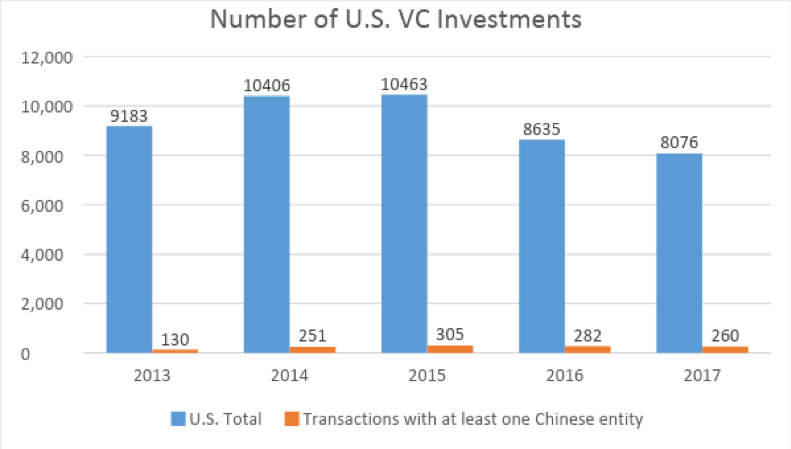

In addition to LP commitments, commercial data providers also track direct investment into U.S. VC-backed startups. These providers capture the funding round amount, the date the round closed, and the names of some, if not all, of the participating investors. Using this information, databases can cross-check the location of the investor to determine its headquarters, therefore relatively accurately capturing the number of investments where at least one Chinese investor participated (see below). Because these sources report only the total amount of funding (vs. the amounts specifically contributed by Chinese investors), they materially over state the amount of foreign investment. For example, if a startup closes a $50 million fundraising round and a Chinese entity contributed $10 million of the capital, this might be reported as $50 million transaction that a Chinese entity was part of since it is not known that the Chinese entity contributed only 20 percent of the capital for that round. Given these limitations, I would encourage policymakers to exercise caution in using these estimates as a key rationale for supporting legislation or regulatory changes.

Using this methodology, we know that in 2017, U.S. venture-backed startups raised $84 billion across 8,076 transactions, of which 260, or 3.2 percent of all deals, included at least one Chinese entity [see previous link]. These 260 transactions had an aggregate deal value of $9.3 billion, which includes capital from all investors (again, not only Chinese entities).

source: PitchBook [total value of funding round includes capital invested by Chinese entities and non-Chinese entities]

In addition, as is the case with the Chinese limited partners, the vast majority of direct Chinese investors are either private family offices or private consumer internet companies (e.g., Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent) — not Chinese sovereign money. Thus, the Chinese government is not likely a material investor in venture-backed U.S. companies.

Structure of VC funds mitigates concerns over Chinese investment

The venture capital industry shares the goal of this committee and FIRRMA to protect U.S. innovation and ensure that U.S. critical technology is not used to harm our competitiveness or security. It is important to understand, however, that the structure of VC funds effectively protects sensitive information of startups from disclosure to investors into the fund.

By way of background, the relationship between the investors in venture capital funds, LPs, and the individuals charged with managing the fund and making investments (general partners, or GPs) is governed by a limited partnership agreement (LPA). The LPA defines not only the economic relationship between the parties, but also the nature of involvement of the LPs in the investment entity. By design, the LPs have in fact very limited rights in the ongoing fund entity — they are expressly entitled to defined economics resulting from the investments and to regular financial reporting from the fund — but have no say in investment decisions and no ability to garner portfolio company information other than at the discretion of the GPs. In addition, the LPA contains a confidentiality provision that binds the LP to maintain in confidence all such information as provided by the GP. Thus, as a matter of course, information disclosure to LPs is minimal and largely related to valuation and accounting-related information to ensure that the LP understands its current economic position in the fund.

In most cases, venture capitalists will sit on the board of directors of the companies in which they invest and, as a result, will also owe duties of confidentiality directly to the shareholders of those companies. Thus, to the extent a venture capitalist were aware of proprietary technology in use or being developed by the company, she would not be in a position to share that with LPs. In fact, most LPAs have an express provision in them in which LPs acknowledge that GPs may have independent fiduciary duties to their companies such that they may be restricted in their ability to share any information with LPs.

Thus, as a matter of common practice in the industry, most GPs provide LPs with quarterly financial reports of the fund’s performance and, in some cases, investment letters that highlight interesting trends/new investments on which the GP may be focused. In my experience, in no case will those updates include details on intellectual property or other proprietary information — as noted above, not only might that violate the GP’s duties to the company, but it would be against the financial self-interest of the GP to risk disclosing information that might leak to the marketplace and risk impairing the financial value of the asset.

GPs also typically host an annual in-person meeting for their LPs. These meetings generally are comprised of financial updates on the various investment funds and presentations from the GPs on areas of investment focus for the firm. Some annual meetings will also include a few entrepreneurs from the portfolio, who will provide an overview of the company they are building. These are naturally high-level presentations focused on the market opportunity and do not include any meaningful disclosures on sensitive technology or intellectual property. For example, a company might disclose that it is seeking to create a drug to slow down the aging process by using machine learning techniques, but it would not describe any of the details of the technology. Again, the reason for this is quite simple — the companies go to extreme measures to maintain the confidentiality of their intellectual property, so any general disclosures can create risk.

FIRRMA should be improved by changes that will avoid unintended consequences

FIRRMA is well meaning legislation intended to deal with a real challenge. However, as drafted FIRRMA produces many questions about the filing obligations of U.S. venture capitalists when a fund has any amount of foreign LPs. FIRRMA also raises significant questions when a U.S. startup accepts foreign investment, even if that investment is for a small stake in a startup or when co-investing with U.S. investors. We appreciate the opportunity to work with this committee and FIRRMA’s sponsors to modify the bill in key ways that keeps in place its intended effects while avoiding serious issues for startups and venture capitalists.

Ambiguity in FIRRMA’s impact on VC funds should be clarified

As drafted, FIRRMA is ambiguous in its application to a venture capital fund with foreign LPs. FIRRMA appears to be written with foreign direct investment in mind, i.e. a scenario where a foreign person invests capital directly into a company. [Sec. 3(a)(5)(B(iii) of FIRRMA specifies that a “covered transaction” is inter alia an “investment (other than a passive investment) by a foreign person in any United States critical technology company or United States critical infrastructure company, subject to regulations prescribed under subparagraph (c).”] The legislation does not specifically speak to the common practice of a foreign person that invests in a U.S. venture fund, which in turn invests in a critical technology company. We are concerned that this ambiguity — especially when combined with a broad grant of rule-making authority to CFIUS — will cause unnecessary confusion, cost, and burden for the venture capital industry, as venture firms will be left without a clear understanding of whether they must file with CFIUS and under what circumstances.

We recommend FIRRMA be amended to clearly specify that U.S. venture funds with foreign LPs are not implicated by the covered transaction definition, nor does the fund take on foreign personhood for purposes of FIRRMA merely because it has foreign LPs. This crucial clarification is in line with the spirit of the bill, which importantly removes ‘passive investment’ from the definition of a covered transaction. [FIRRMA Sec. 3(a)(5)(B(iii) and Sec. 3(a)(5)(D)] As detailed above, LPs in VC funds are by definition passive investors and therefore more should be done to provide clarity in this regard.

The ambiguity of FIRRMA causes concern that venture funds would need to file with CFIUS as a precautionary measure merely because it has a partially foreign LP base and might invest in a U.S. critical technology company in the future. This would be an unfortunate distraction from supporting the development of new startups. It would also be a bizarre outcome because when a VC fund is raised, it is impossible to know whether the fund will ultimately invest in a ‘critical technology’ company. After all, a VC fund lasts approximately a decade and invests in new enterprises that in the vast majority of cases do not exist at the time the fund is raised. This can be contrasted with a foreign person that invests directly in a U.S. critical technology company, as the foreign person will likely know whether that company is ‘critical technology’ under FIRRMA at the time of the investment. It would also be distracting, inefficient, and nonsensical if a venture fund were required to file with CFIUS each time it made an investment in a startup out of its fund with foreign LPs. Startups move quickly and are in need of capital to scale their business. It would be impractical if a VC fund needed pre-clearance from the government before it provided that capital. I understand from CFIUS practitioners that CFIUS clearances can take four months or more from the time the parties begin working on the filing — that is not a time frame compatible with venture investing.

FIRRMA should not stifle foreign strategic investors that have become a key aspect of startup financing

A growing and important component of startup financing is participation by so-called foreign strategic investors, like investment arms of multinational corporations. These investors are increasingly providing capital to U.S. startups alongside U.S. venture funds as co-investors, especially in later-stage deals where the amount of capital raised by the company is significantly larger than what would be raised by an early-stage company. These foreign strategic investors are important to the entrepreneurial ecosystem because frequently when a startup is raising capital, there will be multiple entities that will participate in the round as co-investors to ensure the startup is able to raise the capital it needs to grow.

It would be an unfortunate outcome if the foreign co-investor of a U.S. VC fund needed approval from CFIUS to participate in an investment round, as that would complicate and slow the round even in situations where the foreign investor is taking a minority stake in a round for a minority stake of the company. For example, imagine a U.S. critical technology startup that is raising capital from four entities, three of which are U.S. VC funds and the fourth of which is a foreign strategic investor. In that round, the company sells 20% of the company for $50 million and the foreign investor takes 25% of the round, resulting in a 5% ownership interest in the company. With a 5% ownership stake, the foreign strategic investor will not have access to sensitive information that is the concern of FIRRMA, but it may need to file preemptively with CFIUS out of caution to determine whether the investment is acceptable. Ideally, the foreign strategic investor would clearly meet FIRRMA’s passive investment test and be assured the investment was acceptable, but unfortunately that test is quite narrow and it will be a judgment call for the investor as to whether they qualify. This could result in a U.S. startup missing out on key investment capital as the company seeks to grow. As a practical matter, investment rounds are generally very competitive and decisions often are made in a matter of weeks if not days. Thus, filing requirements (or uncertainty) that would jeopardize this timeline are likely to mean that the investors will be prohibited outright from participating in the investment opportunity.

To avoid this situation, FIRRMA should specify that a CFIUS filing is not needed if the foreign strategic investor takes a de minimis stake in the startup (such as in the hypothetical above), as in that scenario the foreign strategic investor is a de facto passive investor but might fear it does not meet the tightly drafted passive investment text. Another helpful change would be to broaden the passive investment test to provide assurance to foreign strategic investors that they are not implicated by FIRRMA [FIRRMA Sec. 3(a)(5)(D)]. For example, the requirement that a foreign person not receive more “nontechnical information” than other shareholders should be modified, as this information is immaterial to the aim of FIRRMA. Our industry would be pleased to work with FIRRMA’s authors and the Banking Committee to provide further detail on how this section can be improved.

FIRRMA should give CFIUS additional authority to exempt additional countries

FIRRMA grants CFIUS the authority to exempt countries from the definition of a “covered transaction” if the country meets certain requirements. One factor CFIUS is directed to consider is “whether the United States has in effect with that country a mutual defense treaty” [FIRRMA Section 3 (a)(5)(C)(ii)]. This factor should be broadened to capture a wider universe of U.S. strategic partners that ought to be exempted from the covered transaction definition, as many of these countries are important sources of capital for high-growth U.S. companies.

Conclusion

Our industry appreciates the interest the Banking Committee and FIRRMA’s authors have paid to this important matter for national security. We encourage policymakers to proceed deliberately and with caution as it tackles this issue. As my testimony demonstrates, the modern startup investing ecosystem is complex and care should be taken to ensure it is not disrupted in a way that harms the ability of startups to grow. Our industry stands ready to work with policymakers as reforms to CFIUS are concerned.