TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The public market situation for healthtech can seem pretty depressing. Recently IPOed healthtech stocks are underperforming the broader market, with some falling 95%+ from their IPO—meanwhile, more traditional companies like UnitedHealth and Eli Lilly are near all-time highs.

Unsurprisingly, some in the healthcare community have begun to extrapolate these disappointing results to the broader landscape of venture-backed healthtech companies and the thesis behind it: can real, high-growth, high-margin, highly defensible businesses be built in healthtech?

Our answer: yes, absolutely.

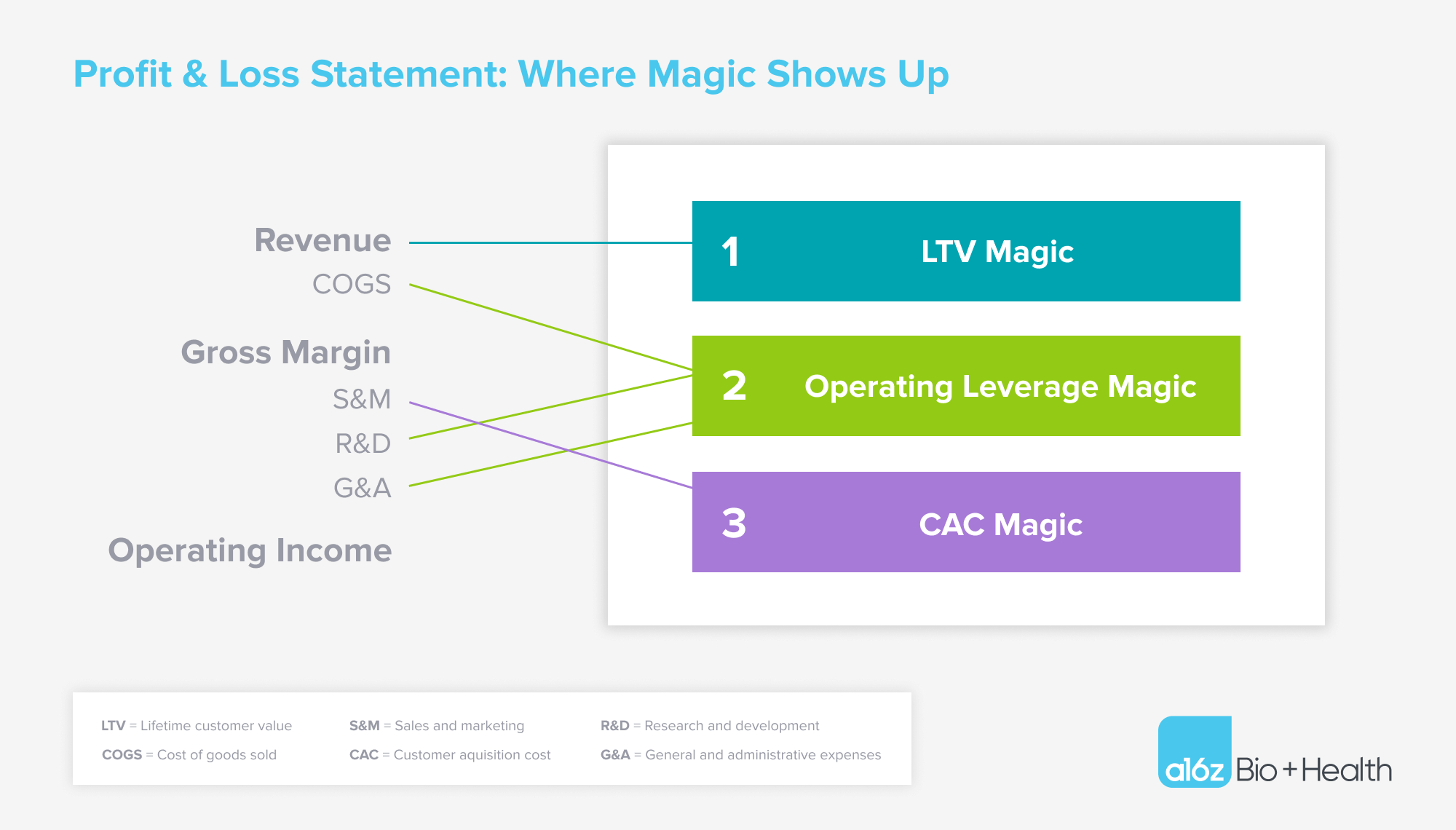

The most important companies in healthtech—and those that make the most enduring impact on the greatest number of patients—will take advantage of the opportunities in healthcare (namely: enormous spend, disproportionate labor-to-capital ratios, and high switching costs) by deploying the strategic advantages of many of the largest tech companies today: increasing customer lifetime value (LTV), expanding operating leverage, and declining customer acquisition cost (CAC).

The companies that do this will exhibit strong business model quality, or as we like to call it, “magic.”

Quantifying magic

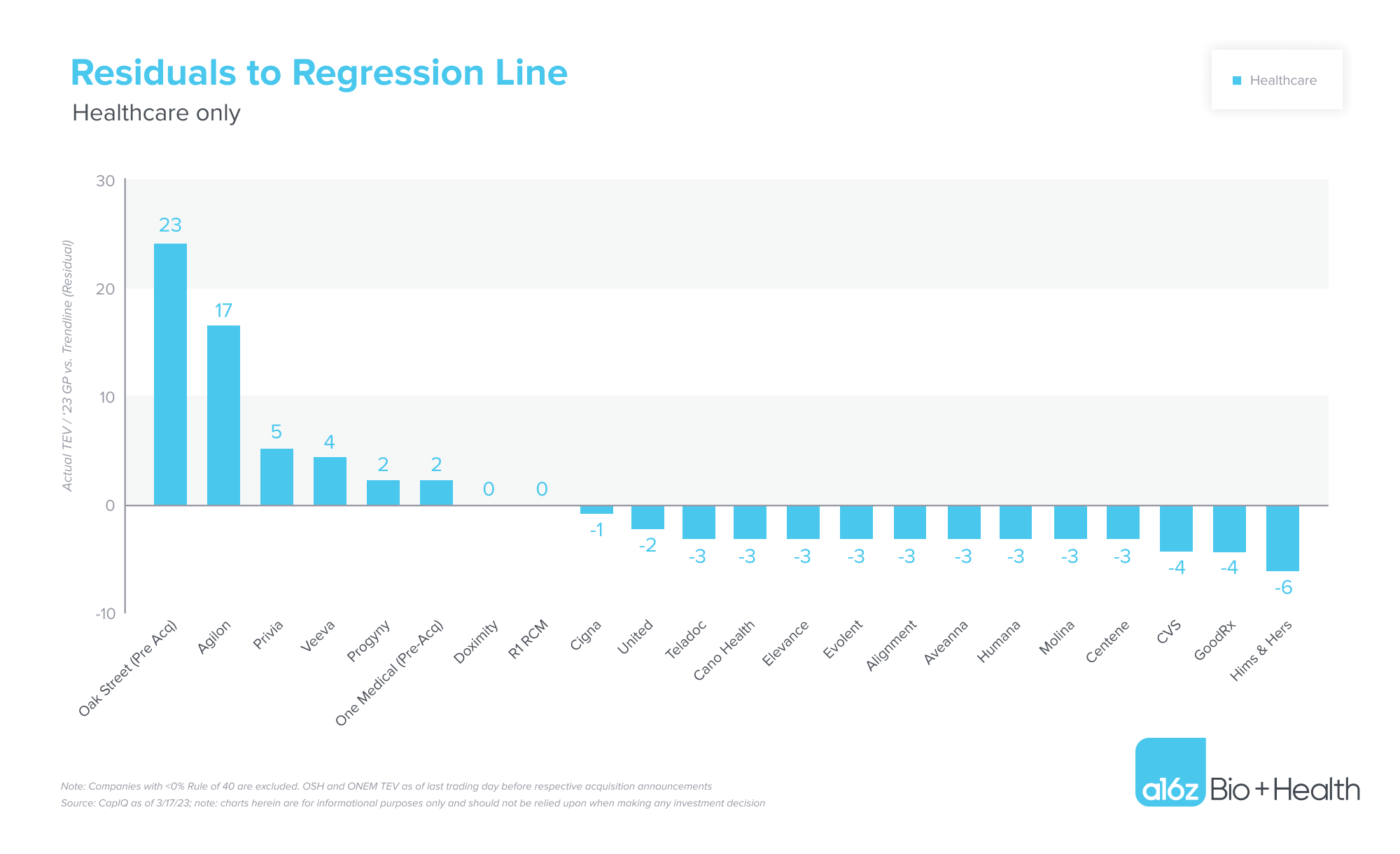

If modern healthtech companies were fundamentally doomed in the public markets, we’d expect to see them poorly valued even when accounting for the observable quality of the business. As we’ll show, that’s not the case.

Controlling for quality

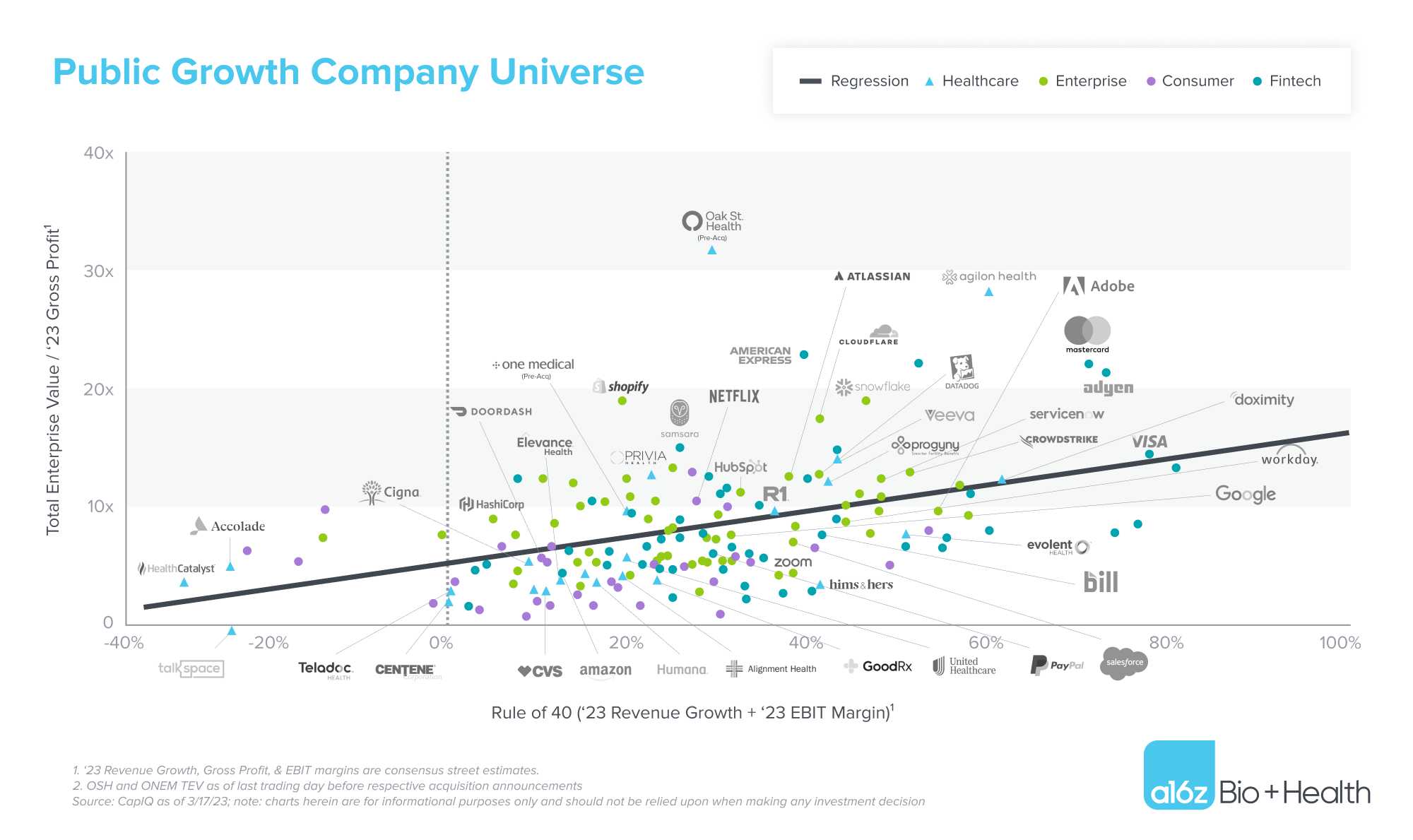

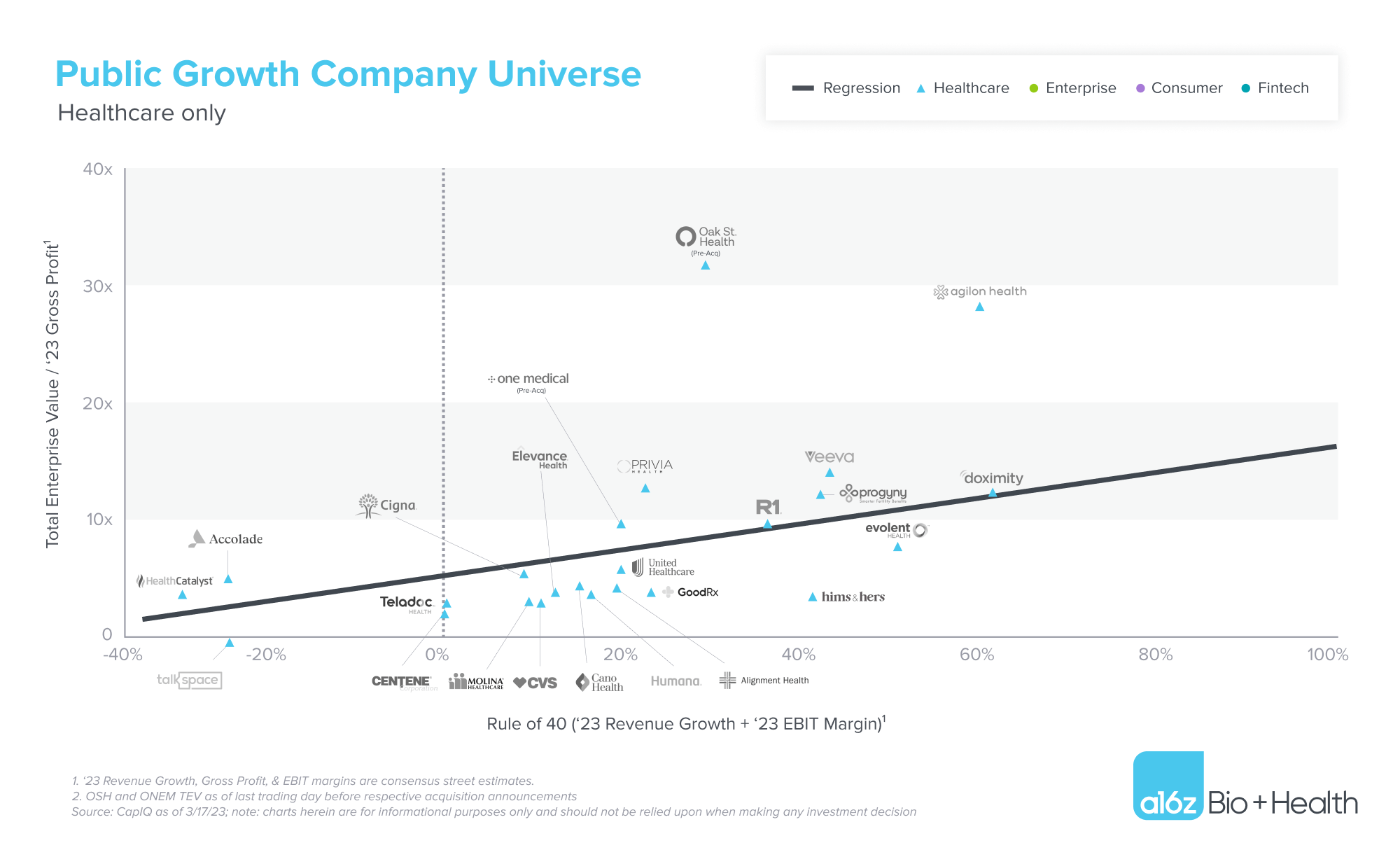

For this analysis, we used a metric called Rule of 40—a composite measure of revenue growth rate and profit margin. When we plot the universe of growing public healthcare (excluding biotech), enterprise, consumer, and fintech companies by efficiency score vs. valuation multiple (Total Enterprise Value over Gross Profit), we see a reasonable correlation.

This makes sense! The businesses with higher rule of 40 scores are able to grow quickly without burning much. We think of this graphical exercise as trying to “control” for the observable quality of a business—after all, if we wrote a piece that concluded growing quickly while burning little (e.g. high rule of 40) automatically translated to a better valuation multiple, you might accuse us of tautology.

Is healthtech doomed in the public markets?

Meanwhile, if healthcare businesses were structurally underappreciated, we would expect to see a cluster of light blue triangles below the regression line—that is to say, they would trade at structurally lower multiples than peers in the enterprise, consumer, or fintech world that had the same measure of observable quality (rule of 40).

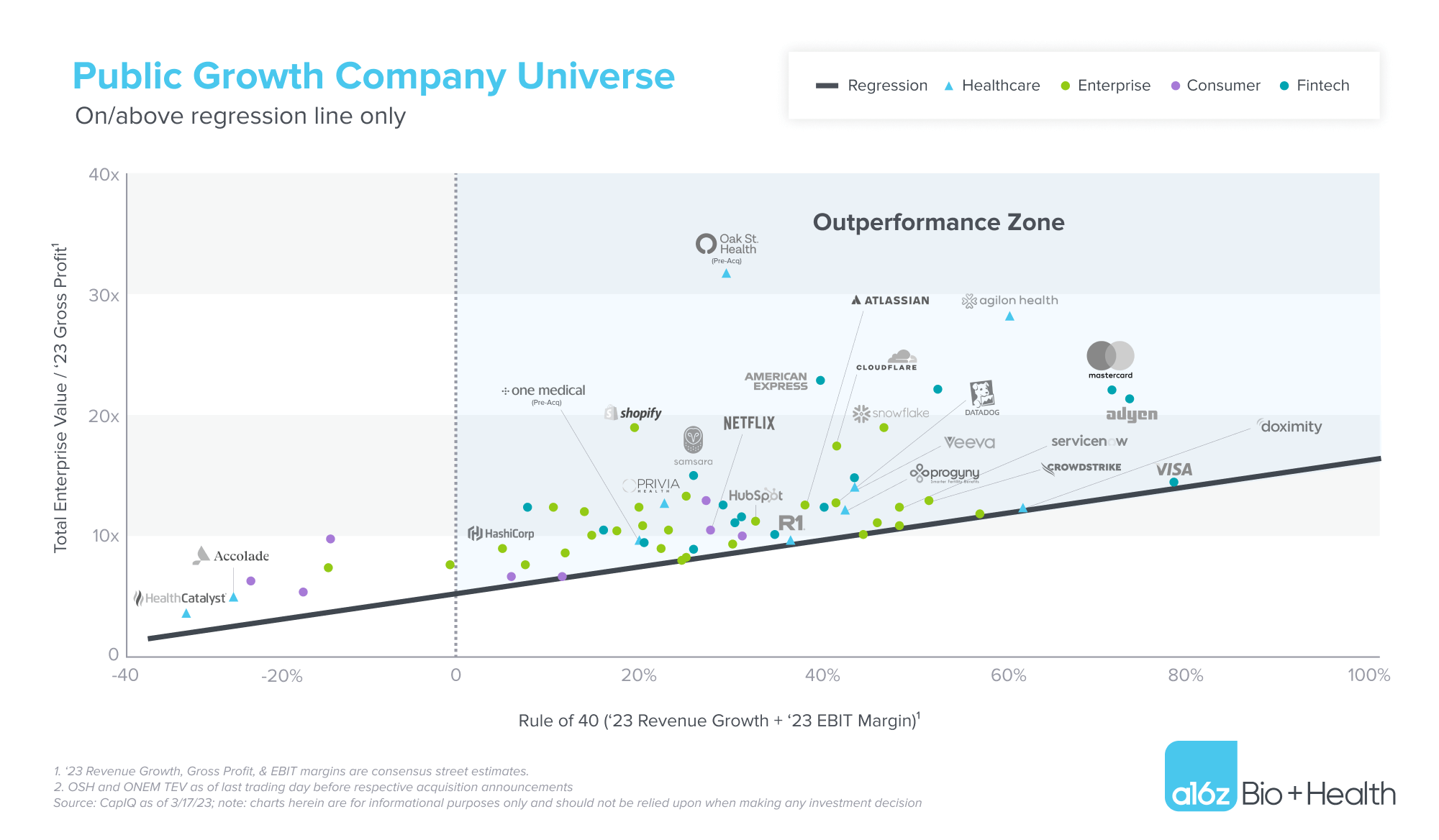

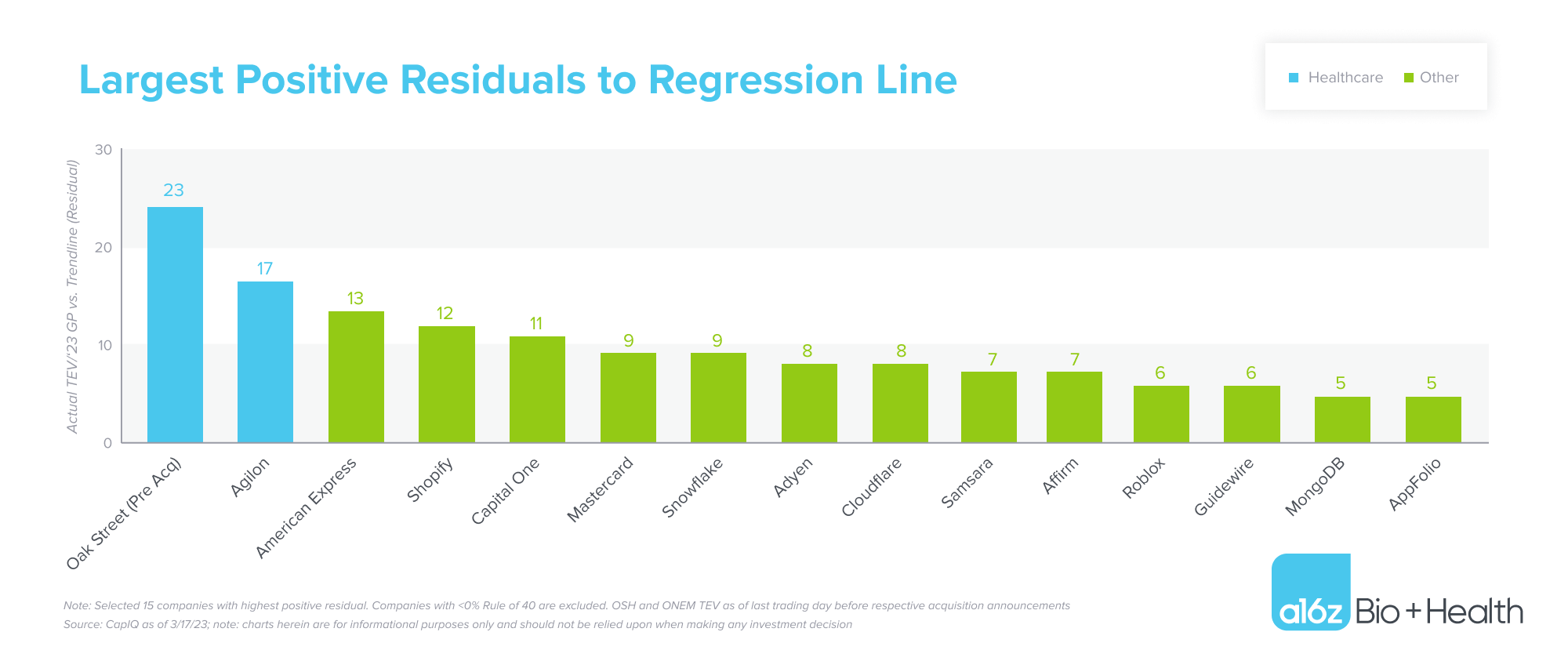

But this is not what we see. In fact, some of the dots with the largest positive vertical distance to the line (positive residuals) are healthcare companies—Oak Street (pre-acquisition announcement), Agilon, Veeva—while others like Doximity, R1, Progyny, and One Medical (pre-acquisition) are right on the line, alongside peers like Visa, Datadog, Intuit, and Airbnb.

Our conclusion: healthcare companies are not structurally under-valued in the public markets. And digging into the drivers of the positive residuals in healthcare reveals some key insights for early-stage founders studying what the public market is telling us for how to build valuable businesses.

To that end, what do these positive residual outperformers all have in common?

At least one thing: magic in their business model, such that public market investors seem to believe these businesses will be able to predictably, efficiently, and defensibly generate cash flow for a long time in the future.

Where magic shows up

We see several forms of magic that can drive business model quality, and which can be used as a model for current and future founders as they think about the long-term direction of their companies.

LTV magic: increasing revenue streams from current customers

LTV magic: Stickiness –> revenue retention

The stickier a product, the greater retention a company can expect, creating LTV magic. Some enterprise software businesses achieve this by becoming so embedded in their customers’ business operations and payment flows that they become practically indispensable. One of the most common forms of this motion is building a system of record and engagement; being the digital backbone of other organizations provides pricing power and widening revenue streams.

One way to interpret the high residual that Veeva receives, for example, is that investors expect Veeva’s customers to not only stay with them for a long period of time, but to spend more during the course of the relationship, compounding revenue growth over time. Even at a $2.1B revenue scale, Veeva exhibits exceptional gross and net revenue retention with a ~24% EBIT margin.

Healthtech companies that embed their software platform into their customers’ core workflows—becoming an anchor to their care delivery and/or life sciences technology stacks—can build in strong defensibility for years to come.

LTV magic: “Platform-ability”

Multi-sided network businesses enjoy the compounding advantage of network expansion, leading to the ability to layer additional services. In other words, as a company’s platform expands, the company can more easily add additional, diversified components to that platform with little incremental cost.

For example, Doximity’s network effects have the follow-on benefit of allowing the company to quickly build a pharma-facing business on top of the existing network. Similarly, at Flatiron Health, a strong provider network enabled the company the opportunity to build a pharma-facing, real-world evidence generation business on top.

This platform potential is why we care about moats before gross margins. A defensible and retentive customer base enables a company to increase LTV without a proportionate increase in costs, eventually driving outsized margins.

Operating leverage magic: Declining marginal cost to serve customers

Operating leverage magic: COGS level

Companies that develop meaningfully differentiated technology to solve their customers’ business problems can capture a disproportionate share of the value they generate.

As we often argue, software’s near-zero marginal cost dynamics allow for exponential revenue growth with high gross margins. In other words, software can allow a business to maintain a declining marginal cost while serving additional customers.

This declining marginal cost, in turn, provides startups with more room for error on operating expenses. This is true for both software-as-a-service (SaaS) and tech-enabled services companies—although services companies tend to have higher labor costs that scale proportionally to revenue, reducing the room for error.

We continue to be especially optimistic about healthtech startups that leverage the latest large language models to deliver their product with minimal COGS impact. If software bringing the marginal cost of distribution to near zero was impactful, just imagine what’s possible as generative AI brings the cost of creation down to zero.

Operating leverage magic: Operating expenses (OpEx) level

Similarly, there is a category of businesses that create magic at the operating expense level. This operating leverage is the result of a model that grows revenue without a proportionate increase in centralized spend. This is similar to COGS level magic in that it’s often accomplished with software, but it is different in that it’s tied to overall operating expenses (specifically R&D and G&A costs), rather than marginal cost per product or service (i.e COGS).

One way to interpret the high residual that Oak Street and Agilon receive is that investors value their unique dynamic of having costs largely borne at the local market level. This strategy allows these two companies to maintain modest operating expenditure growth at the central business level as they scale within and to new markets. In other words, the market appears to give Agilon and Oak Street credit for impacting the cost of care without having to hire many central clinical staff (a huge operating expense for traditional healthcare services businesses).

This can drive even more pronounced advantages for healthtech companies as they enter into commercial risk agreements and capture the upside of the value they deliver.

CAC magic: Declining marginal cost to acquire customers

CAC magic: B2B2C

Relatedly, one of the most efficient ways to acquire new customers is by accessing groups of high-need patients through partnerships or acquisitions with entities that already maintain those relationships.

Agilon and Oak Street have successfully implemented this type of magic by signing up provider groups or Medicare Advantage plans that are financially responsible for large populations of patients. As a result of this acquisition strategy, as well as the related OpEx level magic we discussed above, these companies have moved toward profitability quickly, with the expectation that they will convert gross profit to free cash flow at an unusually high rate over time.

We can’t help but imagine future healthtech businesses that are capable of impacting the cost of care for large, high-need patient populations with increasing sales and marketing efficiency, through a variety of creative go-to-market motions (e.g. bottom-up sales).

CAC magic: Network effects

It’s no secret that we at a16z love network effects. Network effects happen when a product or service becomes more valuable to its users as more people use it, creating a flywheel effect of increasingly capital efficient growth.

For Doximity, strong network effects lead to declining incremental CAC; the value of Doximity to the 10,000th user is much stronger than it was to the 1,000th user. Over time, the Doximity platform becomes easier to sell.

We interpret Doximity’s favor in the public markets as investors valuing Doximity’s network effects, with the company’s high user engagement and retention expected to be durable long into the future.

Healthtech companies that tap into network effects can maintain or even improve efficiency at scale, providing a powerful competitive advantage over time.

Building a magic (cash flow) machine

Ultimately, no entrepreneur wants to spend over a decade building something that is undervalued at scale. Not to mention the fact that higher public valuations can increase a company’s ability to pursue its mission.

All of this analysis really comes down to one thing: cash flow. Specifically, investors are ultimately underwriting a business’s ability to predictably generate a lot of cash over the long term.

The way to control your own destiny is to focus on finding and showing the magic that will enable you to be a cash flow machine.

The 6 forms of magic highlighted above are by no means exhaustive, but hopefully give a sense for the ways in which some healthtech companies are being given high positive residual valuations in the public markets. Note that this is orthogonal to whether the business is a tech-enabled service or a SaaS play; both can be magic cash flow machines!

Conclusion

Healthtech isn’t dead—it’s just grossly misunderstood. We’re excited to see how the next generation of healthtech founders incorporate the various forms of magic we’ve outlined, or another type we haven’t even thought of, to build real, high-growth, high-margin, highly defensible businesses.

As the firm that popularized the phrase “software is eating the world,” we’re believers that tech will enable massive, enduring companies in healthcare. We’re particularly hopeful about the possibilities of AI, as well as the opportunities for companies that leverage their magic to take on risk and meaningfully improve patient care.

We remain healthtech optimists.

-

Jay Rughani Jay Rughani is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he invests in AI across healthcare and life sciences.

-

Mehul Mehta is a partner on the Growth investing team, focused on late-stage companies building in the bio and healthcare industries.

-

Julie Yoo is a general partner on the Bio + Health team at Andreessen Horowitz, focused on transforming how we access, pay for, and experience healthcare.

-

Scott Kupor is an investing partner focused on growth-stage companies building in the bio and healthcare industries.