This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

IN THIS EDITION

- Fiscal policy to aid small businesses

- For fintech, a heightened sense of purpose

- Credit cycles in an economic crisis: lessons from 2008

- Mortgage rates are so low, they’re high

- Goldman Sachs waives March Apple Card payments

- Square to become a bank

Want more a16z?

Sign up to get our best articles, latest podcasts, and news on our investments emailed to you.

Thanks for signing up.

Fiscal policy and fintech to help small business

Alex RampellIn order to get out of this unprecedented economic crisis, we need immediate fiscal help targeted at those with fragile balance sheets, particularly small businesses and low income Americans. Forcing businesses to shut (despite consumer demand) is akin to eminent domain of income and solvency in the name of public health—a good cause. The closure of businesses obviously impacts employment, with unemployment claims shooting up in record numbers. When people lose their livelihood, they cease spending, entering a vicious deflationary cycle that monetary policy cannot help.

Fixing this is not as simple as giving money to those who lose their jobs because we need to make sure they have jobs to go back to! We need to address the businesses we have temporarily eminent domained in the name of public health. How do we *quickly* identify, adjudicate, and disburse funds to these 30 million small businesses across the US?

Given that “the government can remain bureaucratic longer than you can remain solvent,” how do we determine which businesses deserve bailouts and which don’t? For how much? How does the federal government even know who or what is a business? How do we prevent fraud? What about previously failing businesses? Businesses and business owners need the most help with fixed costs—think rent, utilities, equipment financing, etc. Providing a “holiday” for fixed payments simply pushes the pain to a whole other set of businesses who count on those payments as their revenue.

Here’s where fintech comes in. In a world where most businesses have a normalized set of financials (thanks to QuickBooks, NetSuite, Xero, Freshbooks, etc.), the government can extend credit or grants for certain fixed cost line items. Denmark and the United Kingdom are trying this with payroll, but that’s a problematic oversimplification, given the myriad cost structures of small businesses (many have fixed costs well in excess of payroll)—not to mention the prevalence of sole-proprietors that the federal government likely has no record of.

Many, many people will need to be let go or furloughed if businesses are to survive—having centrally planned zombie companies helps nobody. But we can combine upsized unemployment insurance with an upsized Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to put enough money into people’s pockets to hopefully provide a spark of demand. Or give people prepaid credit cards with a set amount of money on them that must be used by end-of-year, once the quarantine is lifted.

Other ideas:

- Eliminate payroll taxes for three months to allow small businesses to “cut pay,” yet pay their employees the same. After-tax pay becomes the “salary,” therefore encouraging businesses to keep jobs.

- Provide incentives for weathering the storm: If you keep your payroll constant you get a COVID-19 Patriotism Bonus at the end-of-year for a large percent of your payroll. Having some skin in the game helps with risk sharing.

Now, how do we do these things quickly? We need private enterprise to help distribute these products and benefits. Quickbooks, Xero, Square, Stripe, Netsuite, Kabbage, BlueVine, Fundbox, and others could spin up “apply for aid” buttons and SMB lenders could add “government aid” as an option. These companies already have direct connectivity with tens of millions of small businesses and can identify (since they have the customers!), adjudicate (since they have the financials!), and disburse (since they access the bank accounts!) immediately.

Obviously, the health and safety of people comes first. But we have to fight an economic virus that could wipe out most jobs and livelihoods, too.

For more on how monetary and fiscal policy can aid small businesses, listen to a16z’s 16 Minutes on the News podcast.

- The Greenfield Strategy: AI-native startup Bingo James da Costa and Alex Rampell

- Fruits of the Walled Garden Marc Andrusko and Alex Rampell

- AI x Commerce Justine Moore and Alex Rampell

- Investing in Rillet Seema Amble, Marc Andrusko, and Alex Rampell

- How Big Bank Fees Could Kill Fintech Competition (July 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa, Alex Rampell, Angela Strange, and David Haber

For fintech, a heightened sense of purpose

Angela StrangeMany fintech companies are also small businesses, so are suffering from the same fiscal uncertainty as the rest of the economy. But some of these companies are poised to help especially hard-hit lower income Americans and, as such, may become increasingly important in the months ahead. These include fintech companies that provide free banking services (who can afford fees now?), enable early wage access (many can’t afford to wait two weeks), and offer more flexible options for credit scoring or loan repayment.

More than 40 million Americans are on SNAP (formerly known as food stamps); a large majority of them work in adversely impacted industries, such as food service and travel. An app like Propel, which helps users maximize their SNAP benefits through budgeting tools and grocery coupons, is needed now more than ever.

2/ Over 2M SNAP recipients use Propel’s app, @FreshEBT, to manage their benefits. We discovered today that, for Fresh EBT users who work, 88% have lost income due to COVID-19. The average person has lost $500. Our users disproportionately work in retail, food service, etc

— Jimmy Chen (@jimmychen) March 20, 2020

Similarly, Earnin is an app that lets users access their earned wages in real time. Many hourly job workers have been forced to cut their shifts significantly (or entirely). Those that are working need access to their now-diminished pay faster. Workers who lose their jobs and are lucky enough find new employment often can’t afford to wait another two weeks to get paid.

1.We’re seeing an unprecedented drop off in people going to work. Comparing Friday the 13th to the Friday before, people went in to work 20% less in DC, 14% less in NY and 13% less in MA, CO & TX. WY had the smallest drop. #COVID19

— ram palaniappan (@ram180) March 19, 2020

Many incumbent lenders are constrained by rigid credit models. Miss a payment? You’re now a significantly worse credit risk, as Anish notes below. In contrast, many newer fintech lenders use additive models, such as cash flow underwriting or additional signals, to develop a deeper understanding and longer-term view of each consumer’s unique financial situation. By providing more flexibility (even temporarily), these fintech lenders may enable their customers to come out better on the other side.

Many fintech companies are planning carefully to make it through this crisis. They’re also experiencing increased consumer demand for solutions. Those financial services companies who better serve their customer base in a time of need are most likely to see continued loyalty in the aftermath.

- Investing in FurtherAI Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- Oil Wells vs. Pipelines: Two Strategies for Building AI Companies Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- How Big Bank Fees Could Kill Fintech Competition (July 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa, Alex Rampell, Angela Strange, and David Haber

- How Will My Agent Pay for Things? (May 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa, Angela Strange, Seema Amble, and Gabriel Vasquez

- What’s Working in AI, Rebuilding Core Banking (March 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa and Angela Strange

Credit cycles in an economic crisis

Anish AcharyaCredit cycles typically follow economic cycles. After one of the longest periods of benign credit risk, it now appears we’re entering a new phase of both. What can we glean from the last financial crisis, and what lessons can startups take as they navigate an uncertain future?

Amid the turmoil of 2008, that crisis exposed the fragility of credit reports, as well as the inadequacy of the historical underwriting algorithms they’re built on. No underwriting algorithm can factor in inherently unpredictable “black swan” events. Therefore, most underwriters simply ignore these rarities, instead basing creditworthiness on factors like payment history. But what happens, then, when a global economic shock causes much of the world to miss a credit card payment? The underwriting algorithms assume that many people are suddenly and significantly less creditworthy, contributing to a lending pullback. This pullback creates large-scale inefficiency in the system, as otherwise creditworthy individuals are deemed liabilities by traditional lenders.

In 2008, smart startups converted that inefficiency into an opportunity. Companies like Lending Club, Prosper, and Money Lion filled the gap by lending to these miscategorized customers. Though individual companies typically thrive on stability, some startups are antifragile: they prosper in the presence of change. The human impact of this pandemic cannot be overstated. But when we emerge from the crisis, I suspect founders will build some of the generation-defining companies of our time.

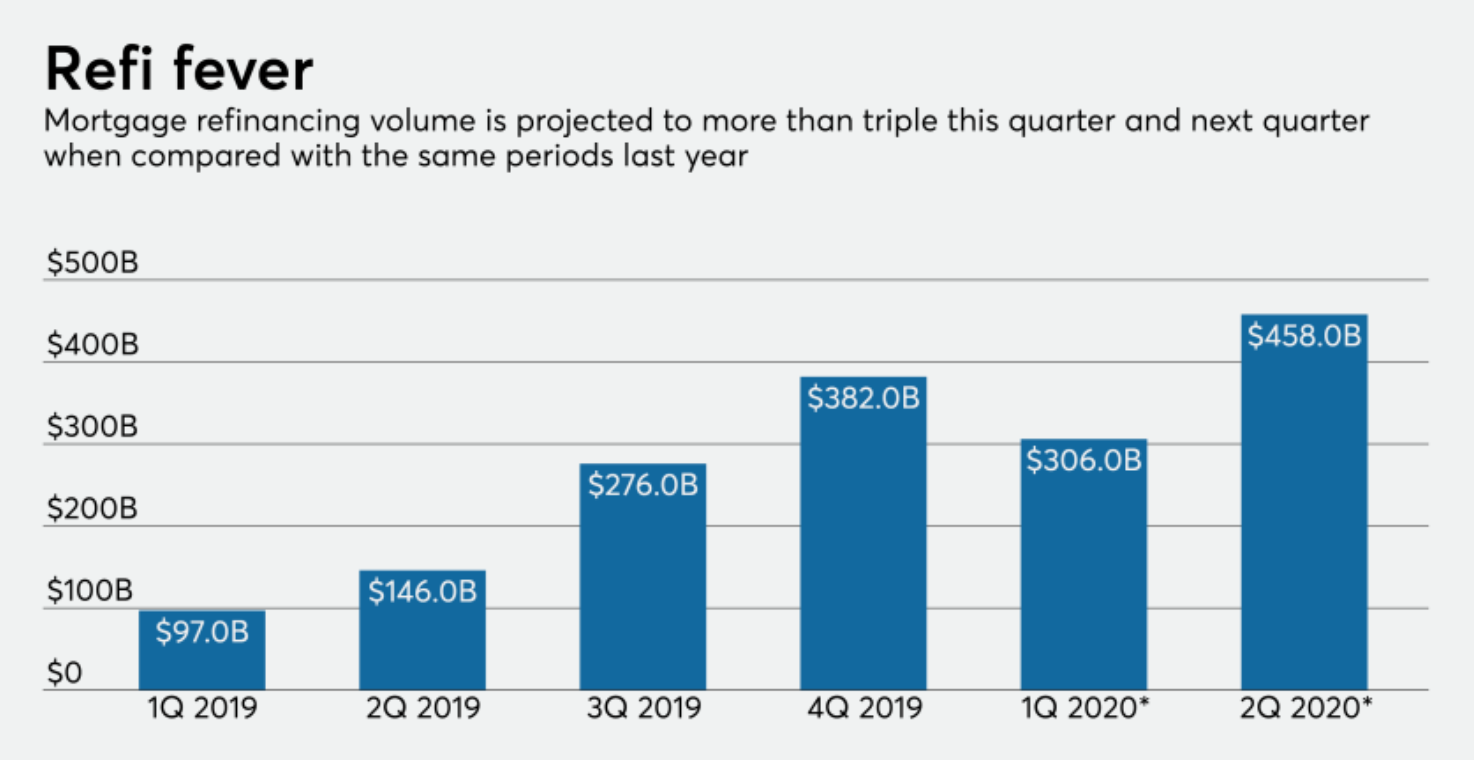

Mortgage rates are so low, they’re high

As the Fed slashes interest rates to near-zero over the economic fallout from the coronavirus, mortgage rates have dropped to their lowest point in 50 years. As a result, banks have been overwhelmed by demand for refinancing. That surge has been so pronounced, in fact, that some lenders have actually raised rates, as demand exceeds their ability to process applications.

Consulting Freddie Mac’s website, it looks like there has never been a better time to refinance. Head to a mortgage rate comparison website, though, and you’ll find another story. Advertised mortgage rates are actually quite a bit higher.

Anyone who has refinanced a mortgage knows it’s a painful and time consuming process. Though it’s essentially a data gathering exercise, refinancing a mortgage requires a tremendous amount of labor. There are approximately 300,000 loan officers in the US who process around 8 million loans per year—a little over two loans per month. Over the past several decades, technology has done little to expedite the system. As a result, most banks cannot scale staff quickly enough to support spikes in demand, particularly those of the scale that we’ve witnessed this month.

But the mortgage refinancing process was a problem long before conditions took a drastic turn. The average refinance takes more than 40 days to close. The inefficiencies are so profound that many choose not to pursue refinancing even when it might make sense. A 2016 report found that Americans pay $20 billion more on interest than they might if they refinanced to a lower rate. That equates to $3,000 of excess interest per homeowner.

One of our core beliefs as investors is that fintech will reduce friction in financial services and unlock tremendous value for consumers in the process. The mortgage industry presents an opportunity for positive change, and the recent surge in refinancing volumes provides a tailwind for anyone working to increase the efficiency of the home closing process. Tech-centric mortgage brokerages Better.com and Loansnap deliver efficiency and speed through automation, giving them an edge over traditional brokers. Startups like Modus, Qualia, and Snapdocs are streamlining and digitizing the title and escrow process. Regorra and House Canary are both working to revamp appraisals and home valuation. And companies like TrueWork and Verix provide instant income and employment verification tools to speed initial underwriting.

In concert, the efforts of all these players are spurring improvements across the mortgage process. By doing so, they enable homeowners to take advantage of changes in the market, rather than leave money on the table.

Goldman Sachs waives March Apple Card payments

Seema AmbleThis week, Apple announced that it would be waiving March payments for Apple Card customers who sign-up for its Customer Assistance Program. In anticipation of hard times ahead, Apple is making a consumer-friendly move to retain its customers. And while other card issuers—mostly banks—have offered assistance measures such as waiving late fees or deferring payments, Apple’s offer is among the most generous.

So why the noble move by Apple and, by extension, Goldman Sachs? It’s a bid to build goodwill and brand loyalty. A 2018 Fed report found that 39 percent of Americans don’t have the cash to cover a $400 emergency expense; in those cases, many Americans turn to credit card debt. By offering a reprieve during hard times, Apple hopes that its card is the first one you repay when you’re able.

So how do Apple and Goldman Sachs justify the cost of this policy? On a simplified basis, if we assume consumers have an outstanding balance of $1,000 and an APY of 20% (the range varies from 12.99% to 23.99%, based on credit profile), then Apple is forgoing about $16 per customer. Not bad compared to Apple’s customer acquisition cost, which is likely much higher. And as consumers continue to use the Apple Card—something that’s likely to increase, as physical stores are shuttered by quarantine—Apple continues to receive interchange fees.

As unemployment increases and more Americans struggle to make ends meet, lenders could see higher default rates for credit cards, as they did in the last recession. Finding capital as a lending base will become difficult. Most fintech lenders rely on funding from banks and investors or securitization; the cost of both options is likely to increase significantly as default rates rise. The fintech companies best positioned to weather the storm are those with a diversified business, beyond lending—or those backed by banks like Goldman.

- Investing in Lio Seema Amble, James da Costa, Eric Zhou, and Brian Roberts

- Need for Speed in AI Sales: AI Doesn’t Just Change What You Sell. It Also Changes How You Sell It. Seema Amble and James da Costa

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- The AI Application Spending Report: Where Startup Dollars Really Go Olivia Moore, Marc Andrusko, and Seema Amble

- The Rise of Computer Use and Agentic Coworkers Eric Zhou, Yoko Li, Seema Amble, and Jennifer Li

Square to become a bank

Last month, Varo became the first consumer neobank to be approved for a de novo bank charter by the FDIC. Earlier this month, Square received conditional approval for a de novo “industrial bank” charter, meaning it can serve businesses, not consumers. Pending final approvals, Square plans to launch its bank in 2021.

Square is best known for its point-of-sale product, which enabled small merchants to accept card payments. Over the past decade, the company has expanded its offerings for small and medium-sized merchants to include SMB loans, payroll solutions, analytics, and invoicing features. The launch of a Square bank will allow the company to become more entrenched with these businesses.

From an economic perspective, the addition of deposits allows Square to diversify revenues while lowering the cost of capital to issue loans. It also provides a valuable new data set—a full picture of the sources and uses of merchants’ cash—that Square can leverage to better underwrite its customers.

Following in the footsteps of Varo and Lending Club, Square is steadily advancing toward becoming a bank—and challenging incumbent financial institutions head-on in the process. As uncertainty looms over the US economy, receipt of a bank charter will allow Square to further engage its customers.

More fintech analysis from the a16z Podcast

The ‘Holy Grail’ of Social Plus Fintech

While revealing one’s financial information was once considered taboo, now consumers are more apt than ever to openly discuss money and debt on online platforms. This conversation covers which products and companies are taking advantage of it (some in rather novel ways), how it’s being driven by various subcultures online, and why this shift is happening.

By Anish Acharya, D’Arcy Coolican, and Lauren Murrow

16 Minutes on the News #27: The Economic Virus – Monetary Policy, Fiscal Policy, and Small Business

How do we stop the economic virus, as well as the coronavirus? What’s the difference between monetary and fiscal policy here, how does adjudication and disbursement work, and where could technology benefit?

By Alex Rampell and Sonal Chokshi

16 Minutes on the News #24: Fintech Acquisitions

Intuit acquired Credit Karma. Morgan Stanley acquired E-Trade. Visa acquired Plaid. What’s going on? Why now?

By Anish Acharya and Sonal Chokshi

Sign up here to receive this monthly update from the a16z fintech team.