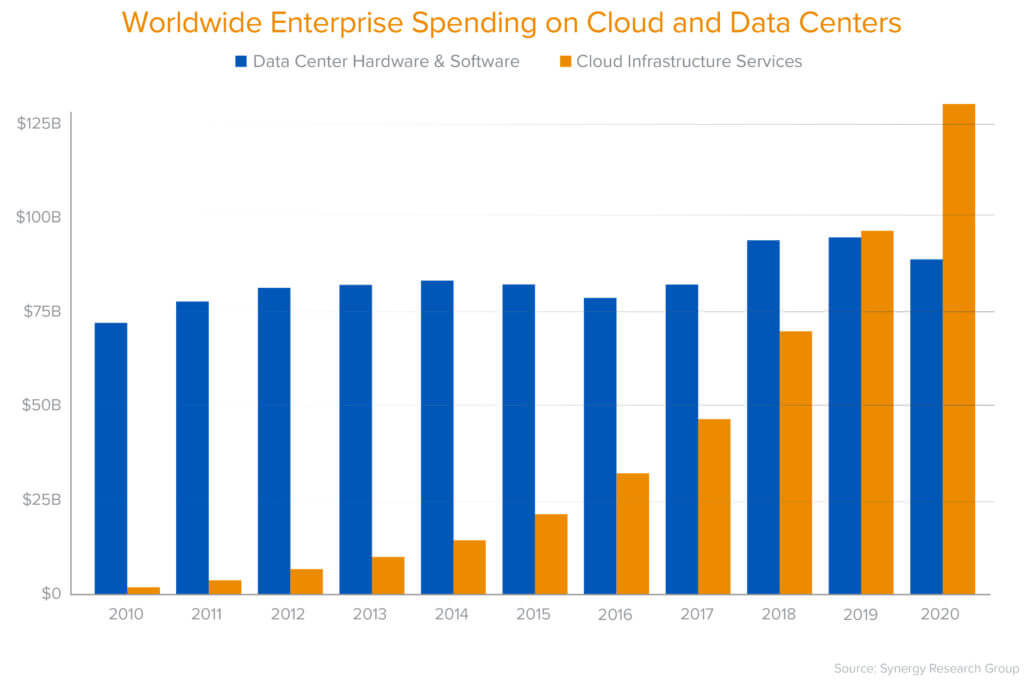

There is no doubt that the cloud is one of the most significant platform shifts in the history of computing. Not only has cloud already impacted hundreds of billions of dollars of IT spend, it’s still in early innings and growing rapidly on a base of over $100B of annual public cloud spend. This shift is driven by an incredibly powerful value proposition—infrastructure available immediately, at exactly the scale needed by the business—driving efficiencies both in operations and economics. The cloud also helps cultivate innovation as company resources are freed up to focus on new products and growth.

source: Synergy Research Group

However, as industry experience with the cloud matures—and we see a more complete picture of cloud lifecycle on a company’s economics—it’s becoming evident that while cloud clearly delivers on its promise early on in a company’s journey, the pressure it puts on margins can start to outweigh the benefits, as a company scales and growth slows. Because this shift happens later in a company’s life, it is difficult to reverse as it’s a result of years of development focused on new features, and not infrastructure optimization. Hence a rewrite or the significant restructuring needed to dramatically improve efficiency can take years, and is often considered a non-starter.

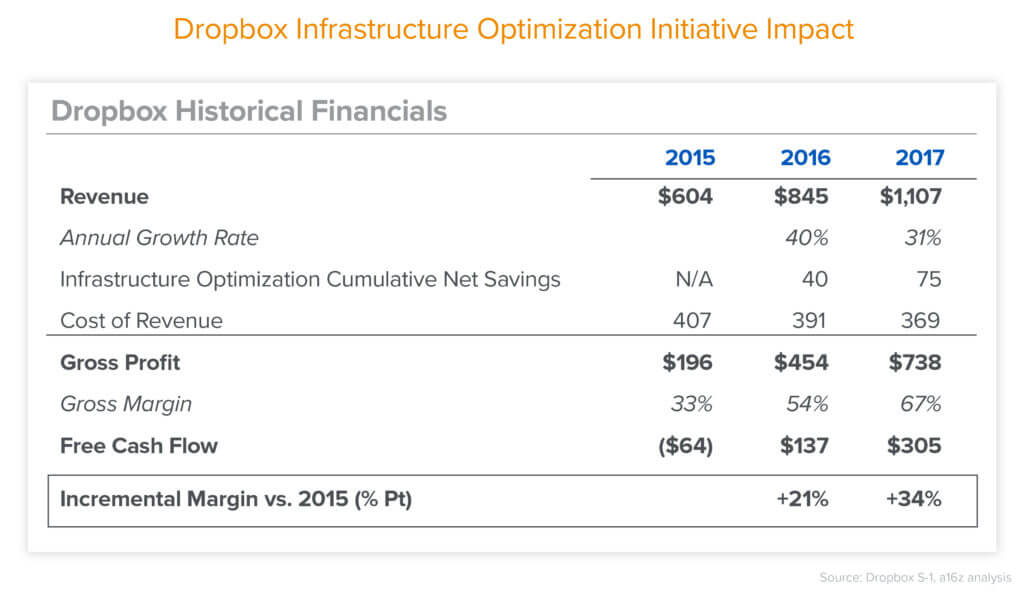

Now, there is a growing awareness of the long-term cost implications of cloud. As the cost of cloud starts to contribute significantly to the total cost of revenue (COR) or cost of goods sold (COGS), some companies have taken the dramatic step of “repatriating” the majority of workloads (as in the example of Dropbox) or in other cases adopting a hybrid approach (as with CrowdStrike and Zscaler). Those who have done this have reported significant cost savings: In 2017, Dropbox detailed in its S-1 a whopping $75M in cumulative savings over the two years prior to IPO due to their infrastructure optimization overhaul, the majority of which entailed repatriating workloads from public cloud.

Yet most companies find it hard to justify moving workloads off the cloud given the sheer magnitude of such efforts, and quite frankly the dominant, somewhat singular, industry narrative that “cloud is great”. (It is, but we need to consider the broader impact, too.) Because when evaluated relative to the scale of potentially lost market capitalization—which we present in this post—the calculus changes. As growth (often) slows with scale, near term efficiency becomes an increasingly key determinant of value in public markets. The excess cost of cloud weighs heavily on market cap by driving lower profit margins.

The point of this post isn’t to argue for repatriation, though; that’s an incredibly complex decision with broad implications that vary company by company. Rather, we take an initial step in understanding just how much market cap is being suppressed by the cloud, so we can help inform the decision-making framework on managing infrastructure as companies scale.

To frame the discussion: We estimate the recaptured savings in the extreme case of full repatriation, and use public data to pencil out the impact on share price. We show (using relatively conservative assumptions!) that across 50 of the top public software companies currently utilizing cloud infrastructure, an estimated $100B of market value is being lost among them due to cloud impact on margins— relative to running the infrastructure themselves. And while we focus on software companies in our analysis, the impact of the cloud is by no means limited to software. Extending this analysis to the broader universe of scale public companies that stands to benefit from related savings, we estimate that the total impact is potentially greater than $500B.

Our analysis highlights how much value can be gained through cloud optimization—whether through system design and implementation, re-architecture, third-party cloud efficiency solutions, or moving workloads to special purpose hardware. This is a very counterintuitive assumption in the industry given prevailing narratives around cloud vs. on-prem. However, it’s clear that when you factor in the impact to market cap in addition to near term savings, scaling companies can justify nearly any level of work that will help keep cloud costs low.

Unit economics of cloud repatriation: The case of Dropbox, and beyond

To dimensionalize the cost of cloud, and understand the magnitude of potential savings from optimization, let’s start with a more extreme case of large scale cloud repatriation: Dropbox. When the company embarked on its infrastructure optimization initiative in 2016, they saved nearly $75M over two years by shifting the majority of their workloads from public cloud to “lower cost, custom-built infrastructure in co-location facilities” directly leased and operated by Dropbox. Dropbox gross margins increased from 33% to 67% from 2015 to 2017, which they noted was “primarily due to our Infrastructure Optimization and an… increase in our revenue during the period.”

source: Dropbox S-1 filed February 2018

But that’s just Dropbox. So to help generalize the potential savings from cloud repatriation to a broader set of companies, Thomas Dullien, former Google engineer and co-founder of cloud computing optimization company Optimyze, estimates that repatriating $100M of annual public cloud spend can translate to roughly less than half that amount in all-in annual total cost of ownership (TCO)—from server racks, real estate, and cooling to network and engineering costs.

The exact savings obviously varies company, but several experts we spoke to converged on this “formula”: Repatriation results in one-third to one-half the cost of running equivalent workloads in the cloud. Furthermore, a director of engineering at a large consumer internet company found that public cloud list prices can be 10 to 12x the cost of running one’s own data centers. Discounts driven by use-commitments and volume are common in the industry, and can bring this multiple down to single digits, since cloud compute typically drops by ~30-50% with committed use. But AWS still operates at a roughly 30% blended operating margin net of these discounts and an aggressive R&D budget—implying that potential company savings due to repatriation are larger. The performance lift from managing one’s own hardware may drive even further gains.

Across all our conversations with diverse practitioners, the pattern has been remarkably consistent: If you’re operating at scale, the cost of cloud can at least double your infrastructure bill.

The true cost of cloud

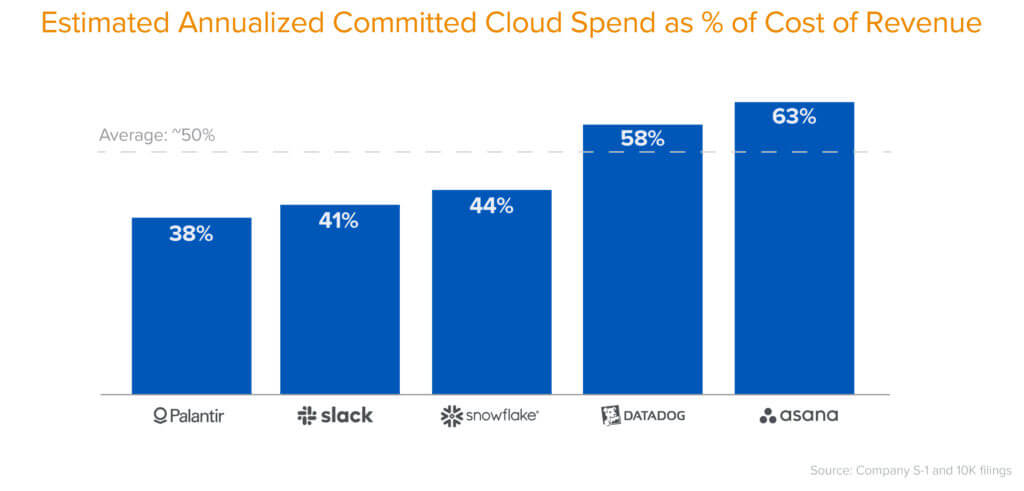

When you consider the sheer magnitude of cloud spend as a percentage of the total cost of revenue (COR), 50% savings from cloud repatriation is particularly meaningful. Based on benchmarking public software companies (those that disclose their committed cloud infrastructure spend), we found that contractually committed spend averaged 50% of COR.

Actual spend as a percentage of COR is typically even higher than committed spend: A billion dollar private software company told us that their public cloud spend amounted to 81% of COR, and that “cloud spend ranging from 75 to 80% of cost of revenue was common among software companies”. Dullien observed (from his time at both industry leader Google and now Optimyze) that companies are often conservative when sizing cloud commit size, due to fears of being overcommitted on spend, so they commit to only their baseline loads. So, as a rule of thumb, committed spend is often typically ~20% lower than actual spend… elasticity cuts both ways. Some companies we spoke with reported that they exceeded their committed cloud spend forecast by at least 2X.

If we extrapolate these benchmarks across the broader universe of software companies that utilize some public cloud for infrastructure, our back-of-the-envelope estimate is that the cloud bill reaches $8B in aggregate for 50 of the top publicly traded software companies (that reveal some degree of cloud spend in their annual filings). While some of these companies take a hybrid approach—public cloud and on-premise (which means cloud spend may be a lower percentage of COR relative to our benchmarks)—our analysis balances this, by assuming that committed spend equals actual spend across the board. Drawing from our conversations with experts, we assume that cloud repatriation drives a 50% reduction in cloud spend, resulting in total savings of $4B in recovered profit. For the broader universe of scale public software and consumer internet companies utilizing cloud infrastructure, this number is likely much higher.

While $4B of estimated net savings is staggering on its own, this number becomes even more eye-opening when translated to unlocked market capitalization. Since all companies are conceptually valued as the present value of their future cash flows, realizing these aggregate annual net savings results in market capitalization creation well over that $4B.

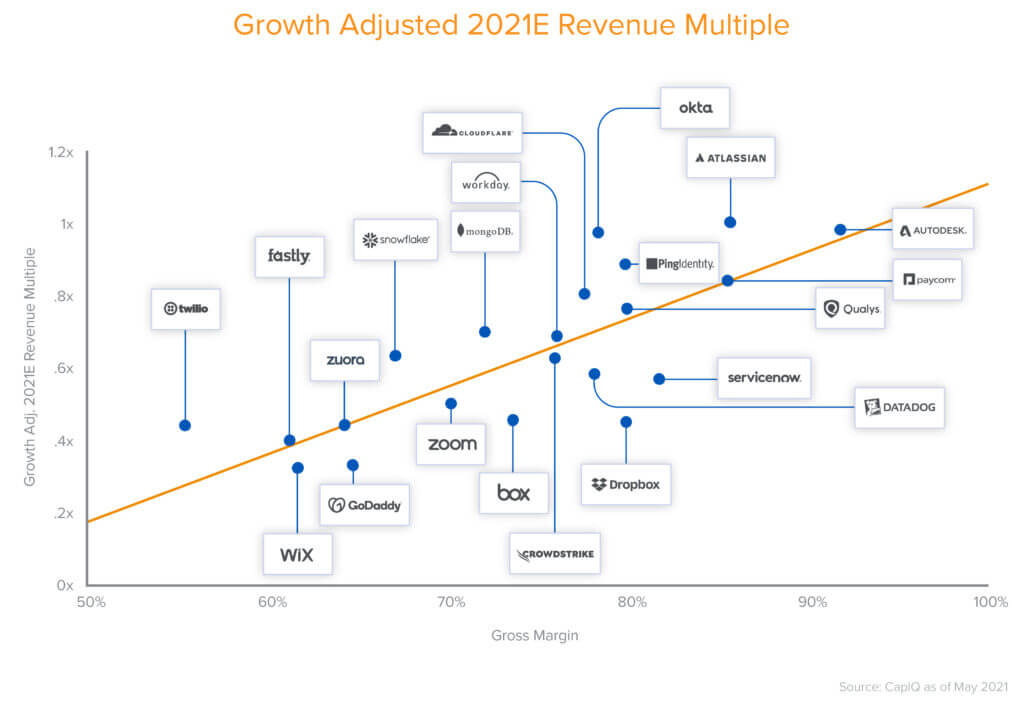

How much more? One rough proxy is to look at how the public markets value additional gross profit dollars: High-growth software companies that are still burning cash are often valued on gross profit multiples, which reflects assumptions about the company’s long term growth and profitable margin structure. (Commonly referenced revenue multiples also reflect a company’s long term profit margin, which is why they tend to increase for higher gross margin businesses even on a growth rate-adjusted basis). Both capitalization multiples, however, serve as a heuristic for estimating the market discounting of a company’s future cash flows.

Among the set of 50 public software companies we analyzed, the average total enterprise value to 2021E gross profit multiple (based on CapIQ at time of publishing) is 24-25X. In other words: For every dollar of gross profit saved, market caps rise on average 24-25X the net cost savings from cloud repatriation. (Assumes savings are expressed net of depreciation costs incurred from incremental CapEx if relevant).

This means an additional $4B of gross profit can be estimated to yield an additional $100B of market capitalization among these 50 companies alone. Moreover, since using a gross profit multiple (vs. a free cash flow multiple) assumes that incremental gross profit dollars are also associated with certain incremental operating expenditures, this approach may underestimate the impact to market capitalization from the $4B of annual net savings.

For a given company, the impact may be even higher depending on its specific valuation. To illustrate this phenomenon [please note this is not investment advice, see full disclosures below and at https://a16z.com/disclosures/], take the example of infrastructure monitoring as a service company Datadog. The company traded at close to 40X 2021 estimated gross profit at time of publishing, and disclosed an aggregate $225M 3-year commitment to AWS in their S-1. If we annualize committed spend to $75M of annual AWS costs—and assume 50% or $37.5M of this may be recovered via cloud repatriation—this translates to roughly $1.5B of market capitalization for the company on committed spend reductions alone!

While back-of-the-envelope analyses like these are never perfect, the directional findings are clear: market capitalizations of scale public software companies are weighed down by cloud costs, and by hundreds of billions of dollars. If we expand to the broader universe of enterprise software and consumer internet companies, this number is likely over $500B—assuming 50% of overall cloud spend is consumed by scale technology companies that stand to benefit from cloud repatriation.

For business leaders, industry analysts, and builders, it’s simply too expensive to ignore the impact on market cap when making both long-term and even near-term infrastructure decisions.

source: CapIQ as of May 2021; note: charts herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision

The paradox of cloud

Where do we go from here? On one hand, it is a major decision to start moving workloads off of the cloud. For those who have not planned in advance, the necessary rewriting seems SO impractical as to be impossible; any such undertaking requires a strong infrastructure team that may not be in place. And all of this requires building expertise beyond one’s core, which is not only distracting, but can itself detract from growth. Even at scale, the cloud retains many of its benefits—such as on-demand capacity, and hordes of existing services to support new projects and new geographies.

But on the other hand, we have the phenomenon we’ve outlined in this post, where the cost of cloud “takes over” at some point, locking up hundreds of billions of market cap that are now stuck in this paradox: You’re crazy if you don’t start in the cloud; you’re crazy if you stay on it.

So what can companies do to free themselves from this paradox? As mentioned, we’re not making a case for repatriation one way or the other; rather, we’re pointing out that infrastructure spend should be a first-class metric. What do we mean by this? That companies need to optimize early, often, and, sometimes, also outside the cloud. When you’re building a company at scale, there’s little room for religious dogma.

While there’s much more to say on the mindset shifts and best practices here—especially as the full picture has only more recently emerged—here are a few considerations that may help companies grapple with the ballooning cost of cloud.

Cloud spend as a KPI. Part of making infrastructure a first-class metric is making sure it is a key performance indicator for the business. Take for example Spotify’s Cost Insights, a homegrown tool that tracks cloud spend. By tracking cloud spend, the company enables engineers, and not just finance teams, to take ownership of cloud spend. Ben Schaechter, formerly at Digital Ocean, now co-founder and CEO of Vantage, observed that not only have they been seeing companies across the industry look at cloud cost metrics alongside core performance and reliability metrics earlier in the lifecycle of their business, but also that “Developers who have been burned by surprise cloud bills are becoming more savvy and expect more rigor with their team’s approach to cloud spend.”

Incentivize the right behaviors. Empowering engineers with data from first-class KPIs for infrastructure takes care of awareness, but doesn’t take care of incentives to change the way things are done. A prominent industry CTO told us that at one of his companies, they put in short-term incentives like those used in sales (SPIFFs), so that any engineer who saved a certain amount of cloud spend by optimizing or shutting down workloads received a spot bonus (which still had a high company ROI since the savings were recurring). He added that this approach—basically, “tie the pain directly to the folks who can fix the problem”—actually cost them less, because it paid off 10% of the entire organization, and brought down overall spend by $3M in just six months. Notably, the company CFO was key to endorsing this non-traditional model.

Optimization, optimization, optimization. When evaluating the value of any business, one of the most important factors is the cost of goods sold or COGS—and for every dollar that a business makes, how many dollars does it cost to deliver? Customer data platform company Segment recently shared how they reduced infrastructure costs by 30% (while simultaneously increasing traffic volume by 25% over the same period) through incremental optimization of their infrastructure decisions. There are a number of third-party optimization tools that can provide quick gains to existing systems, ranging anywhere from 10-40% in our experience observing this space.

Think about repatriation up front. Just because the cloud paradox exists—where cloud is cheaper and better early on and more costly later in a company’s evolution—exists, doesn’t mean a company has to passively accept it without planning for it. Make sure your system architects are aware of the potential for repatriation early on, because by the time cloud costs start to catch up to or even outpace revenue growth, it’s too late. Even modest or more modular architectural investment early on—including architecting to be able to move workloads to the optimal location and not get locked in—reduces the work needed to repatriate workloads in the future. The popularity of Kubernetes and the containerization of software, which makes workloads more portable, was in part a reaction to companies not wanting to be locked into a specific cloud.

Incrementally repatriate. There’s also no reason that repatriation (if that’s indeed the right move for your business), can’t be done incrementally, and in a hybrid fashion. We need more nuance here beyond either/or discussions: for example, repatriation likely only makes sense for a subset of the most resource-intensive workloads. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing! In fact, of the many companies we spoke with, even the most aggressive take-back-their-workloads ones still retained 10 to 30% or more in the cloud.

While these recommendations are focused on SaaS companies, there are also other things one can do; for instance, if you’re an infrastructure vendor, you may want to consider options for passing through costs—like using the customer’s cloud credits—so that the cost stays off your books. The entire ecosystem needs to be thinking about the cost of cloud.

* * *

How the industry got here is easy to understand: The cloud is the perfect platform to optimize for innovation, agility, and growth. And in an industry fueled by private capital, margins are often a secondary concern. That’s why new projects tend to start in the cloud, as companies prioritize velocity of feature development over efficiency.

But now, we know. The long term implications have been less well understood—which is ironic given that over 60% of companies cite cost savings as the very reason to move to the cloud in the first place! For a new startup or a new project, the cloud is the obvious choice. And it is certainly worth paying even a moderate “flexibility tax” for the nimbleness the cloud provides.

The problem is, for large companies—including startups as they reach scale—that tax equates to hundreds of billions of dollars of equity value in many cases… and is levied well after the companies have already, deeply committed themselves to the cloud (and are often too entrenched to extricate themselves). Interestingly, one of the most commonly cited reasons to move the cloud early on—a large up-front capital outlay (CapEx)—is no longer required for repatriation. Over the last few years, alternatives to public cloud infrastructures have evolved significantly and can be built, deployed, and managed entirely via operating expenses (OpEx) instead of capital expenditures.

Note too that as large as some of the numbers we shared here seem, we were actually conservative in our assumptions. Actual spend is often higher than committed, and we didn’t account for overages-based elastic pricing. The actual drag on industry-wide market caps is likely far higher than penciled.

Will the 30% margins currently enjoyed by cloud providers eventually winnow through competition and change the magnitude of the problem? Unlikely, given that the majority of cloud spend is currently directed toward an oligopoly of three companies. And here’s a bit of dramatic irony: Part of the reason Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—representing a combined ~5 trillion dollar market cap—are all buffeted from the competition, is that they have high profit margins driven in part by running their own infrastructure, enabling ever greater reinvestment into product and talent while buoying their own share prices.

And so, with hundreds of billions of dollars in the balance, this paradox will likely resolve one way or the other: either the public clouds will start to give up margin, or, they’ll start to give up workloads. Whatever the scenario, perhaps the largest opportunity in infrastructure right now is sitting somewhere between cloud hardware and the unoptimized code running on it.

Acknowledgements: We’d like to thank everyone who spoke with us for this article (including those named above), sharing their insights from the frontlines.