Cybersecurity is a race where every move by attackers forces a counter. It has always been a cat-and-mouse game: attackers probe for weaknesses, defenders scramble to respond, and the cycle repeats. Over time, this arms race has produced an explosion of categories, frameworks, and labels: so many that the boundaries between them have grown blurry. The result is a landscape that often feels fragmented and overwhelming. Yet one question should always be clear: how does a given security tool actually disrupt the attacker? A way to cut through the noise is to look at defenses in relation to attacker behavior. The cyber kill chain is one such lens, mapping the stages of an intrusion and highlighting where a defense can break the sequence.

Seen through this lens, today’s landscape is especially difficult to navigate. New startups are launching every month and enterprises are deploying more tools than ever before. A typical SOC now manages thousands of daily alerts and more than 30% more tools than just three years ago, yet teams remain chronically understaffed. This combination of tool sprawl, overwhelming data, and scarce talent makes it harder to separate true innovation from incremental features.

In this environment, it is tempting to rely on vendor-defined categories such as SIEM, SOAR, EDR, or XDR, but these labels often obscure more than they reveal because they describe markets, not attack stages. This confusion can also show up in how companies see themselves. Many founders assume they are competing with one another because they share a category label, but when viewed through the kill chain lens, they are often addressing entirely different types of attacks.

The history of security shows that product categories rarely stay fixed. What looks permanent usually turns out to be a temporary response to a new wave of attacks, because defenders bolt on new tools, attackers adapt, and the cycle repeats. Over time, a breakthrough capability makes entire classes of attacks irrelevant and collapses many products into one platform.

In the 2000s, enterprises ran firewalls, IDS, IPS, VPN gateways, and web filters as separate tools until custom silicon made it possible to inspect packets at wire speed and combine them into the next-generation firewall. Endpoint security followed the same path as antivirus, anti-malware, and host intrusion prevention blurred into EDR and later XDR. The current explosion of acronyms across operations, identity, cloud, and data security – from SIEM and SOAR to CNAPP and DSPM – is just another version of the same cycle. At the time, many vendors looked like direct competitors, but in reality most were covering different gaps in the chain until new capabilities collapsed them into a platform. The same dynamic applies today: what may look competitive on the surface often reflects complementary roles along the kill chain.

Each label represents a temporary attempt to keep pace with attackers, not a lasting framework. A better way to understand the landscape is to ask: which stage of the kill chain does this tool disrupt, and how much faster does it help defenders break the attack?

A Brief History: The Cyber Kill Chain

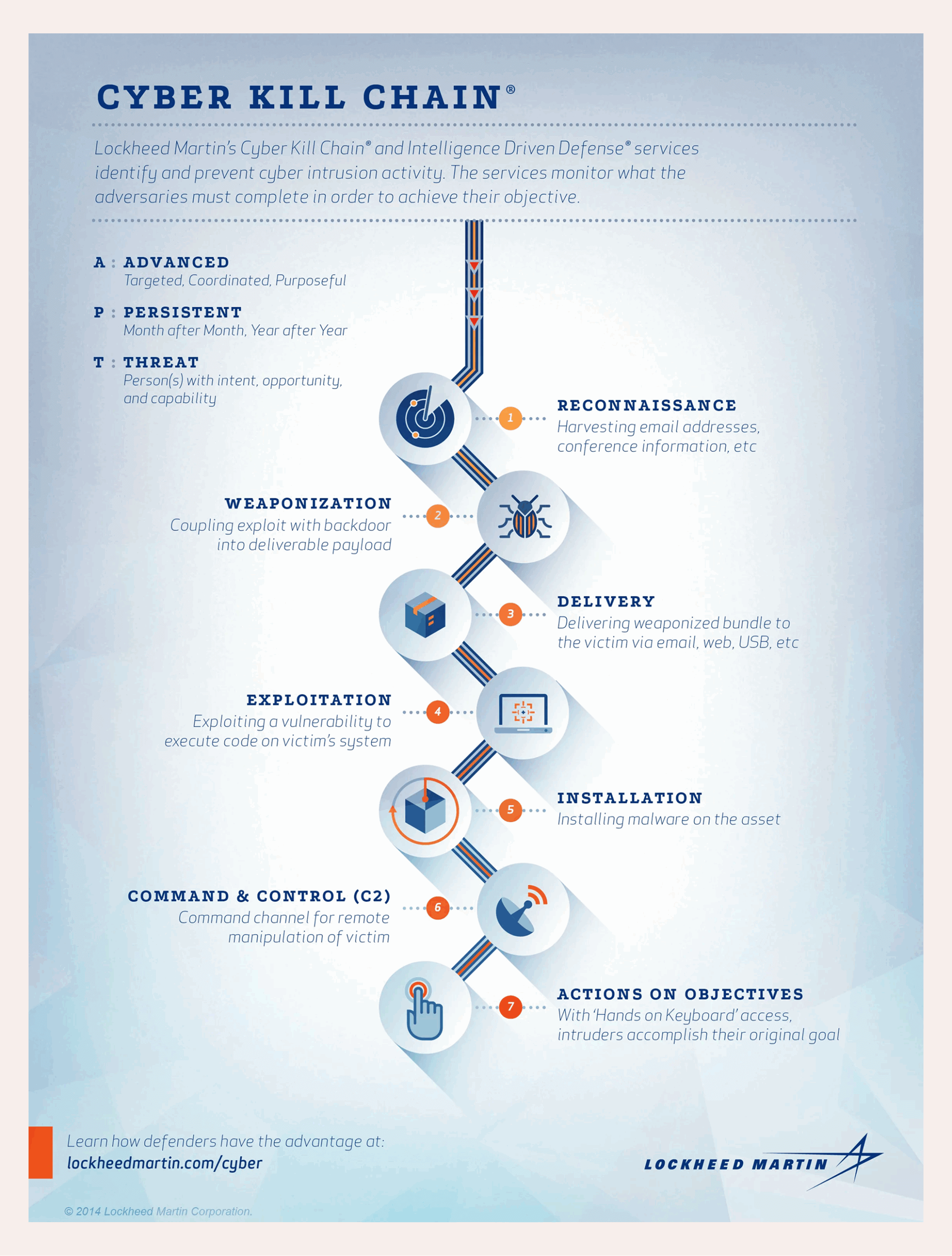

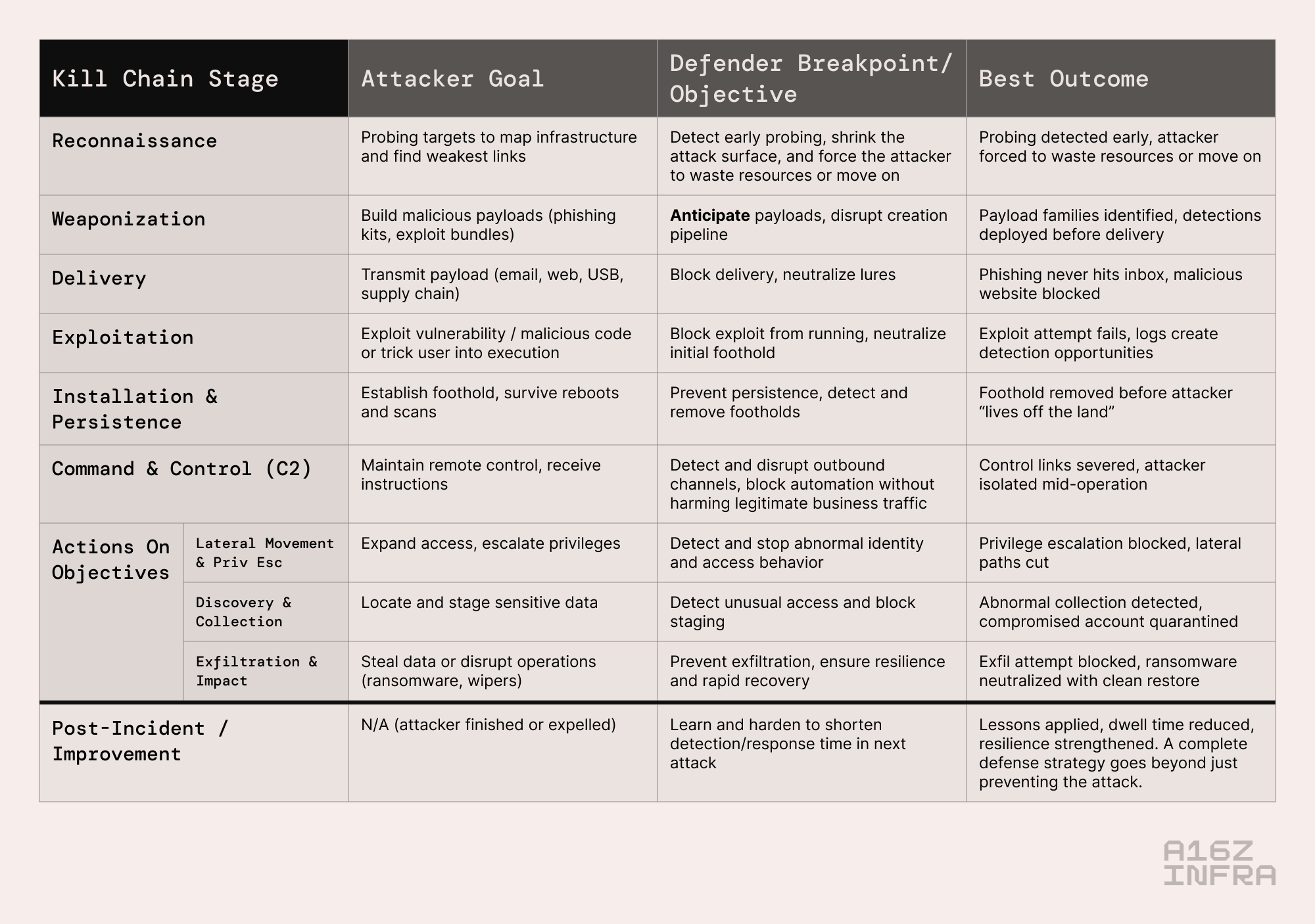

The cyber kill chain, first introduced by Lockheed Martin in 2011, adapts a military concept to describe the stages of a cyberattack. The idea is simple: every intrusion follows a sequence, from early reconnaissance to final objectives, and defenders can disrupt the attack at any stage. The earlier the disruption, the less damage is done.

Practitioners often describe the moment of initial compromise as “boom”. Everything “left of” boom is prevention, and everything “right of” boom is containment and recovery. If the attacker has already reached boom, the defender’s job is to contain the blast radius by detecting lateral movement, cutting off command-and-control, and removing persistence before the objectives are completed. Metrics like dwell time or mean time to detect are just ways of measuring how quickly defenders break the chain once an attacker is inside.

To make this framework actionable, defenders often pair it with MITRE ATT&CK, which catalogs the specific tactics, techniques, and procedures adversaries use within each stage. Where the kill chain shows when an attack can be broken, ATT&CK explains how those attacks play out in practice. Together, they provide both the strategic map and the tactical playbook, helping teams see not only where to intervene but also which behaviors to watch for.

This framing matters because it gives a common language and a practical map. If a tool reliably stops phishing delivery, detects lateral movement, or shuts down command-and-control traffic, it solves a universal weak point and becomes a platform that other tools depend on. By contrast, products that do not clearly tie to a stage of the kill chain often struggle to prove their value.

The kill chain cuts through today’s confusion of acronyms and categories. Instead of asking whether a product is a CNAPP, CWPP, CIEM, CDR, or CASB, the better question is: where in the attack lifecycle does it make a difference, and how much faster does it help defenders detect and respond? Organizing the market by kill chain stage – prevention vs. detection, left-of-boom vs. right-of-boom – provides a simpler and more durable way to understand the landscape than chasing vendor labels.

The AI Wave: The Platform Shift of Today

Attackers are already using AI as a force multiplier. They can generate phishing messages with natural fluency, create malware that mutates faster than signature defenses can track, and scan vast attack surfaces at machine speed. Beyond this, AI can accelerate the discovery of complex zero-days, compounding the asymmetry and pushing the limits of what defenders can anticipate or contain. This shifts the economics of conflict: attackers operate at near-zero marginal cost, while defenders still absorb higher costs with every added control.

This is why bolting AI features onto legacy tools is not enough. Just as next-generation firewalls were not simply ‘firewalls++,’ AI-native security requires rebuilding prevention, detection, and response so that intelligence and automation are the foundation rather than a plug-in.

AI-native products are about embedding intelligence, adaptability, and automation directly into the fabric of detection and response. The cyber kill chain is the clearest way to see why this matters:

- Reconnaissance & Delivery (“left of” boom): AI-native detection platforms don’t just scan for known bad domains or signatures. They learn behavioral baselines across users, assets, and communications, catching subtle probes or phishing lures that would slip past traditional filters.

- Command & Control & Lateral Movement (“right of” boom): AI correlation engines stitch together weak signals (e.g. a login anomaly, an odd DNS request, a privilege escalation) into a coherent narrative that reveals attacker intent. This ability to capture context is what sets LLMs apart from prior detection systems.

AI changes both scale and economics. It can allow defenders to work at attacker speed, to see signals in context rather than isolation, and to adapt continuously as tactics evolve. This transforms defense from a reactive position into one that is proactive and automated. The point is not that AI changes everything in the abstract, but that it makes the kill chain framework more urgent than ever. The critical question for every product is whether it measurably helps break the chain earlier and faster.

AI is the beginning of a new foundation for cybersecurity: one in which intelligence is woven into every layer of protection. AI-native security is the platform shift of today.

Final Thoughts

The history of cybersecurity operations is a cycle of adaptation in which defenders innovate, attackers respond, and new categories emerge to cover the latest gaps. Over time, scattered point solutions are absorbed into broader platforms when a breakthrough makes entire classes of attacks irrelevant. The lesson is that tools alone do not win; what matters is whether they shorten the time to detection and response by breaking the kill chain faster.

For security teams, this pressure is not theoretical. Missing a critical alert or misconfiguring a control can have career-defining consequences. The most valuable solutions are those that measurably reduce that burden – by cutting investigation time from hours to minutes or seconds, by automating containment, or by operating with reliability around the clock.

The north star of security is straightforward: reduce risk by disrupting the kill chain early and decisively. Every product should be judged on where it acts in the chain and how much speed and accuracy it adds for defenders. Frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK remain useful for mapping the tactical details, but the ultimate benchmark is whether a tool helps defenders break attacks sooner and with less effort.

For investors and founders, the kill chain can also help separate true competition. Startups that appear to overlap when defined by acronyms are often tackling different weak points in the chain. This clarity matters not only for buyers deciding what to deploy, but also for investors deciding where to place capital.

The next generation of tools will not be defined by acronyms but by their ability to eliminate attack paths altogether. While attackers will continue to adapt, AI-powered operations give defenders new leverage. The leaders of tomorrow will be the ones who turn the kill chain from a liability into a framework for lasting advantage.

-

Malika Aubakirova is a partner on the AI Infrastructure team at Andreessen Horowitz.

-

Joel de la Garza is a partner focused on information security related investments and other chaos adjacent businesses.

- Follow

-

Zane Lackey is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he focuses on DevOps, cybersecurity, and enterprise infrastructure.