This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe here to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

IN THIS EDITION

- The hype around FICO’s new credit scoring system

- What Credit Karma’s acquisition will mean for its products

- NYC bans cashless businesses

- The trend behind #debtfreeisthenewsexy

- LendingClub buys a rare gem of a bank

- Varo gets approved for a bank charter

- Better tech for tenants

The hype around FICO’s new credit scoring system

FICO announced it will be rolling out FICO 10 and FICO 10T this summer. It’s part of a natural evolution; every few years, FICO tweaks its algorithms and incorporates new data into the formula it uses to assess one’s credit score. This time around, the change has prompted some alarming headlines, stoking fears of plummeting credit scores. But scaremonger headlines are overblown, for a few reasons.

In the short term, the impact of FICO 10 and 10T is likely to be minimal. It takes years for lenders to adopt a new FICO model. Case in point: Currently, the most used FICO score is FICO 8, which was adopted in 2009! Most mortgage lenders still use FICO 4, which was introduced in 2004.

So what’s changing with FICO 10? FICO is now looking at “trending data”—that is, the fluctuation of one’s credit usage and account balances over the previous two years. This could benefit consumers who may have an occasional bad month, but who, in general, keep their credit utilization low. On the other hand, trending data has the potential to penalize consumers who have a longer upward trajectory—for example, those that increase their credit utilization over time. FICO 10 will also weigh personal loans more heavily, penalizing borrowers who rack up additional debt after refinancing credit card debt.

Once adopted, the impact of scoring system updates depends on the type of lender. For larger, more sophisticated institutions, FICO is often just one of several factors considered in advanced underwriting models. Those models build on the data in your credit report and other factors, not solely your FICO score. For smaller, less sophisticated lenders, the effect of new FICO scoring systems may be more pronounced, since those lenders tend to incorporate fewer attributes and often use FICO as a hard cut in a decision tree (i.e., they don’t evaluate anyone below X score).

The question, then: should we care about FICO 10? Not in and of itself. But such news provides a periodic reminder to try to maintain healthy credit habits overall by keeping your credit utilization low and paying debt on time.

Listen to more debate around FICO 10 on a16z’s 16 Minutes on the News podcast.

—Angela Strange, a16z fintech general partner

How Credit Karma’s acquisition will impact its products

Earlier this week, Intuit announced that it’s buying Credit Karma for $7.1 billion. This is a notable deal on many levels: it’s one of the largest acquisitions of a consumer internet company, to date (7x Instagram!), and by far the largest deal in fintech. What did Credit Karma figure out that others may have missed? The company’s approach to product design was key to its success—Credit Karma married the best practices of general consumer product design with a number of specialized insights that were specific to fintech. I learned and contributed to a number of these product design principles as the former GM of consumer product at Credit Karma, a few of which I’ve outlined below.

The questions every fintech product manager should be asking themselves.

—Anish Acharya, a16z fintech general partner

NYC bans cashless businesses

Last month, New York lawmakers passed a bill prohibiting stores, restaurants, and retail establishments from refusing cash payments.

There are many reasons private businesses are trying to eradicate cash, distaste for credit card fees aside. It’s faster and more convenient, because nobody’s counting change. If you’re processing credit cards, you don’t have to worry about employees stealing money. You don’t have to worry about loss in case of a fire. You don’t have to deal with collecting and remitting the cash. So everything just goes on the back-end.

But while there are good reasons to go cashless, the argument is that this ends up being a regressive tax on the poor: that is, while this is not a government tax, it’s a tax that disproportionately punishes a lower socioeconomic class.

So if you’re wealthy, it’s much more convenient to put stuff on your credit card and not carry around cash. However, if you’re poor and can’t get a bank account, you basically have to pay for the privilege of having access to a card. For those unable to get a bank account, there is a world of prepaid cards that you might see in grocery and convenience stores. Normally, you’ll pay a small surcharge, say $2 to $5, on top of the balance you add to the card. So if you buy a $100 card, it might cost $102. Then, unless you stay above some minimum balance, you have to pay monthly fees that might be a sizable chunk of your stored balance; the market leader, Greendot, charges $7.95/month for balances under $1,000, so with a $100 balance, that would deplete to almost zero in a year. Then, if you want to withdraw cash, you have to pay an ATM fee to the prepaid card provider, on top of whatever the ATM is charging you. Here’s an example of what these fees look like to a low income consumer.

Until cheaper alternatives emerge—which is not simply the fault of “greedy” prepaid companies, but rather a whole host of infrastructure and distributions costs that they themselves have to bear—you have to be somewhat wealthy to not be burdened with banking fees. From a consumer’s perspective, you don’t have to pay for the privilege of having cash, but you do for cards.

That said, there’s no question that the world will go cashless eventually. Accepting money electronically is better and much more efficient for the economy at large. But, at present, the fees are too high for both merchants and consumers. The NYC cashless ban is not as Luddite a policy as you might think. It’s intended to be a progressive policy for people who might otherwise be closed out of establishments because of the high cost of accessing a card.

—Alex Rampell, a16z fintech general partner

Financial transparency and the rise of the #debtfreecommunity

Historically, debt was considered private and spending was public. Social media has long been a showcase for the things money can buy—travel! fancy nights out! property!—but over the past few years, the conversation around debt has come to the forefront.

Though the roots of the trend can be traced back to the rise of personal finance personalities like Dave Ramsey and Suze Orman, social platforms now provide an unmediated forum for frank financial discussions. Hashtags relating to personal finance have proliferated on Instagram, for example, from #debtfreecommunity to #debtfreejourney to, my personal favorite, #debtfreeisthenewsexy.

Why does this matter? It’s further proof of shifting societal norms around money. Where revealing one’s financial struggles was once considered taboo, it’s now being recast as an act of solidarity or empowerment. Such financial confessionals can provide a sense of community (“You have about as much debt as 1.5 million other Americans”) and ease feelings of despair or helplessness. From a fintech standpoint, this trend toward transparency presents an opportunity for increased product utility and engagement. The hashtag #debtfreecommunity is a movement; it’s also a model for viral growth.

An entrepreneur’s intent and ethos is evident in the product design. As we become more directly attuned to the scope of society’s challenges with debt—as well as the stories of those who have successfully extricated themselves—the next generation of fintech products is likely to look much different than the financial tools of the past.

—Anish Acharya, a16z fintech general partner

LendingClub buys Radius Bank

Last week, LendingClub announced it would buy Radius Bank. It’s the first time a major US fintech company has acquired a bank since GreenDot bought Bonneville Bank back in in 2011. But Radius is a rare gem: since it’s a digital-only bank, there’s no branch overhead to integrate. And as one of a number of FDIC-regulated banks that have enabled fintech companies to piggyback off their banking licenses, it’s already accustomed to such a partnership. LendingClub, which has struggled over the last five years, is poised to benefit from the acquisition in a number of ways:

- It will no longer rely on an outside funding source (in this case, WebBank) to offer loans. It’s estimated that the deal will save LendingClub $40 million a year in bank fees and funding costs.

- It enables the company to offer new products that it previously needed a partner bank for, like checking accounts.

- It offers more stability than institutional investors, which could pull back funding in a downturn.

- It provides the infrastructure—namely, a core banking system—and regulatory expertise of a bank.

Of course, becoming a bank is not without cost. LendingClub will now face additional capital requirements, compliance requirements, and regulatory scrutiny. In addition, the acquisition process is likely to be slow—between 12 and 15 months—and will require regulatory approval.

Despite those drawbacks, the reality is that marketplace lenders have struggled to compete against banks with what is essentially a commodity product. Given the fierce, margin-sapping competition, lenders are looking for ways to recapture some of the economics.

As community and regional banks struggle to grow and online lenders pursue profitability, it’s likely we’ll see more fintech companies considering acquiring banks—or becoming one themselves.

—Seema Amble, a16z fintech deal partner

Varo approved for bank charter

Earlier this month, after a more than three-year process, the neobank Varo announced that it had been approved by the FDIC to receive a “de novo national bank charter,” meaning it’s on its way to becoming a bank. It would be the first consumer neobank to do so.

By offering an online- and mobile-only banking experience, neobanks have presented themselves as an alternative to opaque, fee-driven traditional banks. But because neobanks are not actually banks, they’ve then partnered with FDIC-regulated community banks. This partnership has afforded neobanks the ability to launch new products quickly, iterate on the experience, and focus full-time on consumers. But as neobanks continue to grow—and reassess their profitability, margins, and cross-sell potential—some are exploring the onerous process of becoming banks themselves.

By becoming a bank, Varo anticipates better unit economics, stronger margins, and the ability to seamlessly launch other core banking products (ie. issue loans with the deposits). Pending final approvals, the neobank plans to transfer its accounts over from its current bank partner, Bancorp, in Q2 this year.

—Matthieu Hafemeister, a16z fintech deal analyst

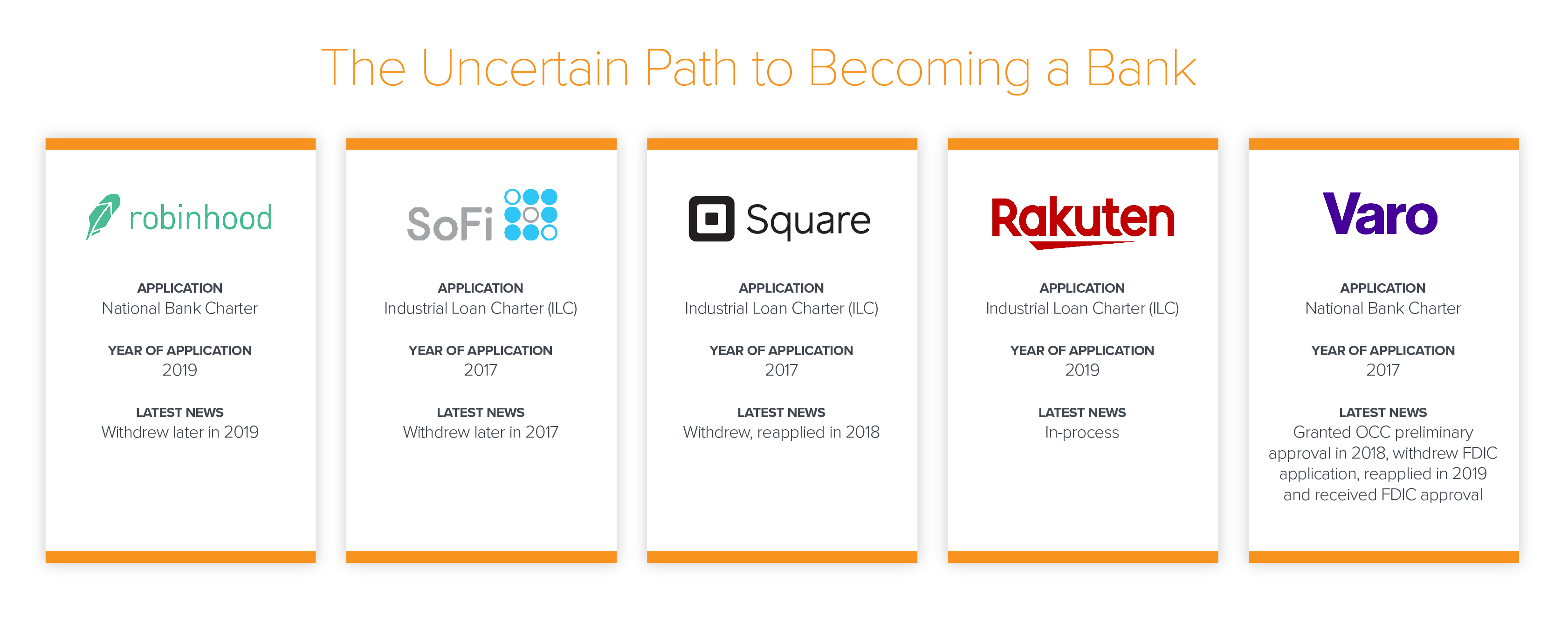

Neobanks’ quest to become banks

Though Varo is inching closer to becoming a bank, its FDIC approval to this point has been far from assured. Multiple fintech companies have made similar attempts, only to withdraw their applications. Some have applied for a national bank charter through the Office of the Comptroller. (Varo was approved via this route.) Others seek an Industrial Loan Charter through Utah, where they can receive FDIC insurance without being subject to bank holding regulation. Amid a complicated regulatory process, several fintech companies have been stymied in their efforts.

—Seema Amble, a16z fintech deal partner

—Seema Amble, a16z fintech deal partner

Tech for tenants

In most of the country, landlords pay real estate brokers one month’s rent for finding a tenant. In New York City, it works the other way around: The tenant pays the broker 10 to 15 percent of his or her annual rent in exchange for being shown the apartment. It’s an understandably annoying experience for the tenant. (“Why am I paying this broker $3,000 for opening a door? I didn’t hire them!”) Earlier this month, a new law banned brokers’ fees, making it illegal to charge the tenant. Pending review by the courts—the ruling has been temporarily blocked, much to renters’ chagrin—the law’s proponents hope it will go into effect later this year.

But this short-lived win for tenants is one small piece of a system that is outdated at best. Renters’ support for the new law is emblematic of a broader frustration with the status quo. The real estate market is strikingly inefficient, whether for home sales (where US agents rake in nearly three times the commission of their British counterparts), mortgage financing (the average mortgage costs more than $8,000 to originate), or, in this case, rentals.

Tenants today are confronted with a variety of broken and archaic processes. Prospective renters are expected to fill out multiple, paper-based applications for each property they visit. Most rent is still paid via paper check. And for those living with roommates, finding and managing cohabitants is often an informal and difficult to navigate process. All of this means there are opportunities to improve the tenant experience.

Companies like Zillow are streamlining the application process by allowing tenants to complete an online application that can be shared with multiple landlords for up to 30 days. This saves tenants time and multiple application fees. Tenants can opt to prove eligibility to landlords by sharing credit history, income, and background check data even before touring a new apartment, ensuring they don’t waste time on properties for which they would fail to qualify. Zillow, Cozy, and Domuso also facilitate online rental payments, replacing cumbersome paper checks. Belong is a full-stack property management company that leverages technology to coordinate payments, repairs, and re-leasing. And several startups are introducing more accessible co-living arrangements. Padsplit, for example, offers low-cost weekly leases for fully furnished single rooms—no down payment required.

Legislative changes like New York’s new broker fee law may or may not deliver meaningful savings to consumers in the long term. But technology has the potential to vastly improve the tenant experience—whether by protecting tenants’ time, saving them money, or sparing them unnecessary hassle.

—Rex Salisbury, a16z fintech deal partner

More from the a16z fintech team

Three Questions for Fintech Product Managers

A framework for honing the product’s design, shaping the user experience, and vastly improving the quality of your output.

By Anish Acharya

When Distribution Trumps Product

How did Bill.com, a decidedly unsexy, 13-year-old product become the dark horse success story of 2019?

By Seema Amble

16 Minutes on the News: FICO changes

By Anish Acharya, Angela Strange, Julie Yoo, and Sonal Chokshi

To receive this monthly update from the a16z fintech team, sign up here.

-

a16z editorial

-

Anish Acharya Anish Acharya is an entrepreneur and general partner at Andreessen Horowitz. At a16z, he focuses on consumer investing, including AI-native products and companies that will help usher in a new era of abundance.

-

Angela Strange is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on financial services, insurance, and B2B software (with AI).

-

Alex Rampell is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he leads the firm’s $1 billion Apps practice.

- Follow

- X

-

Seema Amble is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on investments in B2B software and fintech.

-

Rex Salisbury Rex is a partner on the fintech team at Andreessen Horowitz. He also runs Cambrian, a 3,000+ member community for founders and product leaders in fintech with chapters in SF and NYC. He previously worked in product and engineering at Checkr & Sindeo, automating background checks and mortgages, r...

-

Matthieu Hafemeister Matthieu Hafemeister is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz focused on early stage fintech investments. Matthieu joined the firm in 2017. He first spent time on the a16z Corporate Development team, working on late stage investments across verticals and helping portfolio companies raise downstream capit...