As online video platforms seek a business model beyond advertising, and short videos start to look more and more like commercials, it turns out that commerce may be video’s killer app. And not only could video apps become ecommerce apps, but all ecommerce apps may also have to become video apps.

Various platforms from China show us how this can be done. Take TikTok, the AI-first short video app (now with 1.1B+ total installs) that’s known for its funny videos, memes, and challenges. It currently monetizes through advertising and livestream tipping. But the Chinese version of Tiktok — called Douyin (both owned by Bytedance) — is also a growing ecommerce platform that integrates with popular shopping sites in China. Yet this isn’t a only-in-China phenomenon: YouTube is rolling out tools to help channels sell merchandise, and Instagram has released shopping capabilities to become a “personalized digital mall” as well.

What all of these moves show is the evolution of commerce, especially as viewing habits have shifted from TV to PC to mobile. The first made-for-television commercial aired over 80 years ago; now, with short videos themselves seeming like commercials, the lines between format and content there are blurring. The virality of campaigns like Chiptole’s lid flip challenge (250M+ views) show the power of “user-generated commercials” that people actually want to watch.

Not only do these trends provide a business model for online video beyond advertising, but they show how the next wave of ecommerce will help users discover products, make shopping way more entertaining, and promote interactivity between buyers and sellers (which is something that has been much talked about but not quite realized). Below are some examples of how this is playing out in China, much of which can be adapted to other apps and products anywhere.

#1 Narratives to help consumers fall in love with brands/products

Small- and medium-sized businesses are using short videos as next-generation advertisements. One strategy merchants in China use is to tell the story of a product’s origin — showcasing the factory where consumer electronics are produced, or the farm where cherries are picked. Another strategy is to provide a glimpse into “a day in the life” of the maker — what it’s like to be a fisherman wrestling 20 pound lobsters? — while those lobsters are conveniently available for purchase on the platform.

On TikTok competitor Kwai, 10% of livestreamers have already started to sell goods on-platform, and one popular vertical that’s emerged is fruit ecommerce. Livestreams and short videos are commonly used to advertise the juiciness of fruit, showcase rare varieties, or give viewers orchard tours.

The above product post for newly-ripe blue mangoes is by “Fruit King” Shen Junshan, who in 2018 reportedly made over $150,000. When asked about his income, he winked and replied, “I used to ride a bicycle and now I am driving a BMW. It is as simple as that.”

#2 Video-centric checkout flow

There’s a simple ecommerce checkout flow on Douyin where products can be purchased in as little as three taps. After the short video plays once, the video repeats itself — and this time, a pop-up allows the viewer to tap in and complete a purchase.

Notably, in the suggested products section, clicking “related products” loads viral short videos rather than static product information pages. In addition, on product pages, there is a section for additional short video reviews for the same product, which allows users to see multiple customer perspectives. This is an improvement on the more limited review framework of just star ratings or text, which optimizes for a certain type of reviewer.

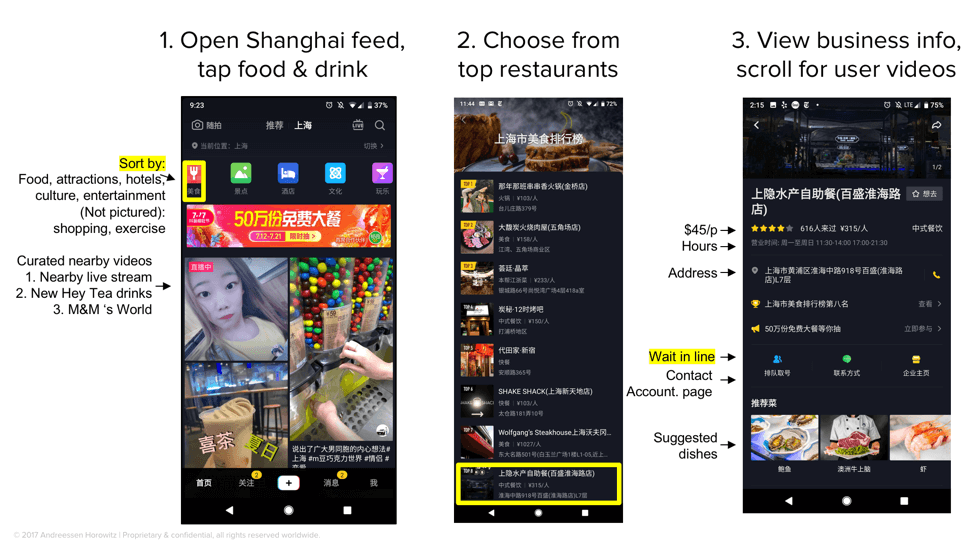

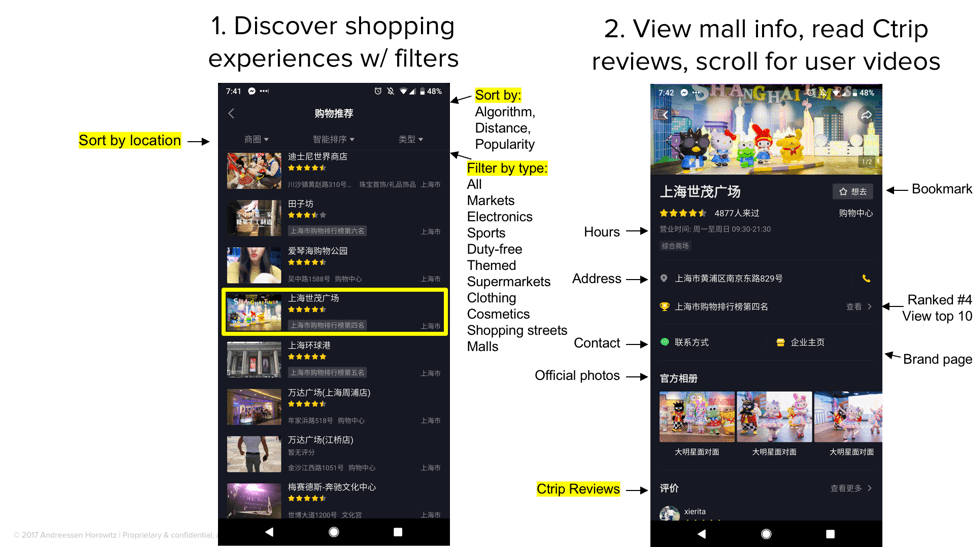

#3 Crowdsourced video city guides

Since many Douyin videos are geo-tagged and automatically categorized into buckets — restaurants, tourist attractions, hotels, culture, entertainment, shopping, exercise — users can browse them to find interesting places to visit and things to do. Businesses are also able to attract new customers by supplementing Douyin with basic information, waitlist support, and coupons.

Meanwhile, shopping reviews are powered by a partnership with travel services site Ctrip. The below video, which was taken at a Nike Factory Store that offers tie-dye shoes made to order, is a form of organic advertising (with over 460K likes to date) that drives customers to visit the mall that houses the store.

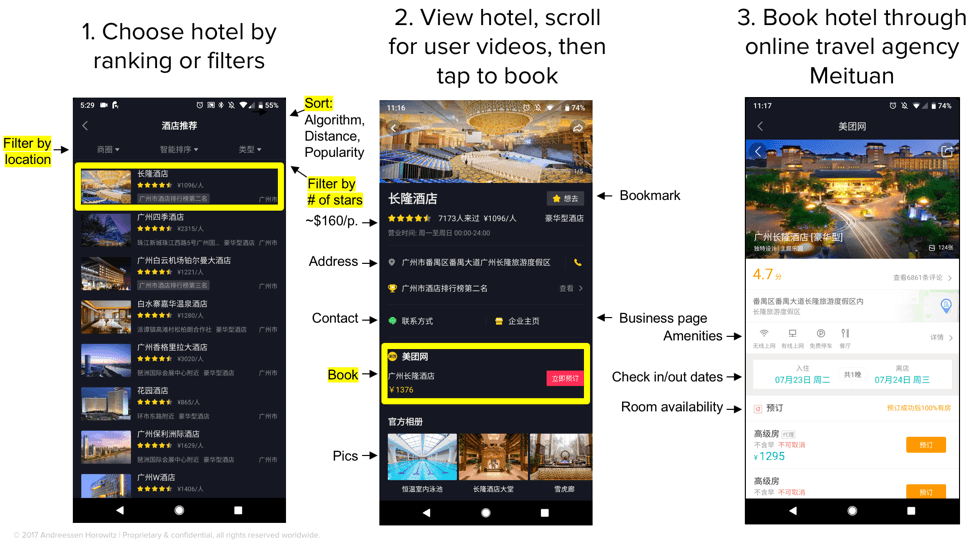

#4 Super app-level convenience

It’s still early days, but Douyin is already showing signs of allowing users to book all sorts of services without ever leaving the app — making it a super app. Since users were already vlogging hotel stays, Douyin decided to leverage that behavior earlier this year by partnering with ten branded homestays for booking stays all from within their app. In the campaign’s first three days, it received 150 million video views and ~$150,000 in bookings. Today, select hotels can still be booked in-app through a partnership with group buying/ coupon site Meituan.

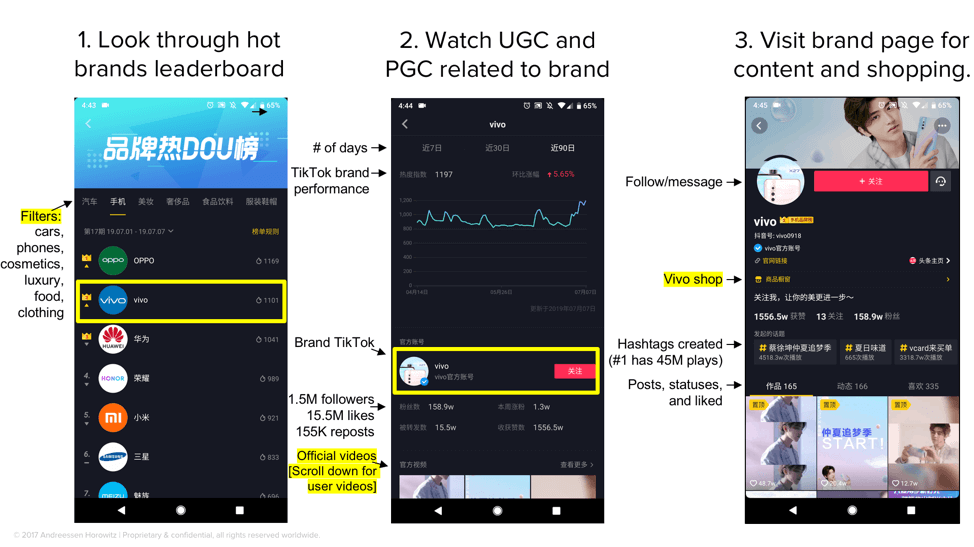

#5 Public analytics for brands

In the brand leaderboards section of the Douyin app, users (and the brands themselves of course) can see how brands are ranking over the last week, last month, or last three months. Rankings are based on several factors: new followers, likes, reposts, user content, etc. Any user interested in a brand can explore the brand page to see official content and user-generated content (UGC) videos, side-by-side. While this means less control for brands, it means more opportunity for them to showcase real user experience videos alongside their own content.

#6 QVC for the smartphone era: demos and live Q&A

If a picture is worth a thousand words, than a video is worth a million, making a far more compelling case than a static-image advertisement. Videos allow people to see a product in action, and for gadgets (like the following phone charger example), that’s especially important:

And unlike email support, text chat, or even a phone call, livestreams allow for users to see answers in real time, whether the questions are their own or from other users.

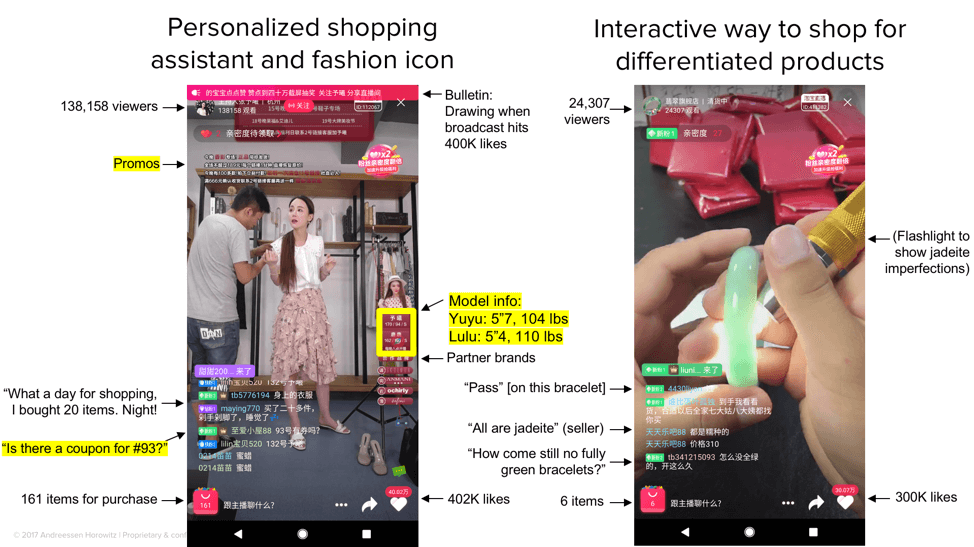

In fashion livestreams, viewers can use chat to ask influencers questions about sizing, request close-ups of fabrics, or discuss what accessories would look good with each outfit. Platforms can further enhances this experience by adding features such as bulletins announcing product lotteries when the stream reaches a certain number of likes, or an overlay showing the model’s height and weight (screens below from Taobao Live).

Left: a fashion influencer models some of the 161 items up for sale, changing outfits every 2-3 minutes. A screen overlay shows her height and weight through the duration of the stream to give users a better sense of what the outfits might look like at home. Right: a jade expert selling bracelets. Because every piece of jade is different, the host uses calipers to show the dimensions of the bracelet and shines a flashlight to show its imperfections. Users purchase the exact jade bracelet shown during the livestream.

Note, livestream ecommerce in China is different than things like Amazon Live, where brands are running the content; in China, most ecommerce livestreams are by individual influencers who sell their own inventory; partner with brands (for a 20-30% commission); and interact with their audiences, going live for almost 8 hours a day.

Finally, on livestreams in Douyin, as well as on almost all of the livestream platforms in China, users are also able to monetize their fame and following by selling third-party products, or their own merchandise, which itself changes the shape of commerce — as well as that of influencers.

– – –

As of August 2018, on China’s largest ecommerce platform Taobao, 42% of the product pages had short videos, up from 15% the year before. The company also generated more than $15 billion in sales through livestreams, up nearly 400% from the year before. The CEO of Taobao observed that livestreaming “is not just bells and whistles” but that “in the future, it will be the mainstream ecommerce model”. This intersection between video, commerce, and content is an important trend to watch.

Furthermore, people have been talking about trends such as interactive, shoppable TV for years, yet it hasn’t come. Now, that could be realized on another platform than television — mobile — where short-form videos become commercials we actually want to watch, and as platforms create features to enable purchases in-app. It’s just the beginning, and could open up opportunities for retailers, makers, content creators, business owners, and especially consumers everywhere.