watch time: 55 minutes

World-class companies aren’t built on technology alone; even the very best products don’t sell themselves. That’s why a smart go-to-market and sales function is critical to capturing market share and growing the company to scale and profitability, even for products whose early growth is driven by a viral bottom-up motion from a loyal base of grassroots users in the enterprise.

But how do you actually build your go-to-market model and sales strategy? How does—and should—the process, the people, and the organizational structure evolve with it? What would such an operation look like at scale? Seasoned sales leader Mark Cranney gives a step-by-step crash course on how to set up and manage a field sales team to sell to complex enterprises such as Fortune 500 companies and government agencies.

Transcript

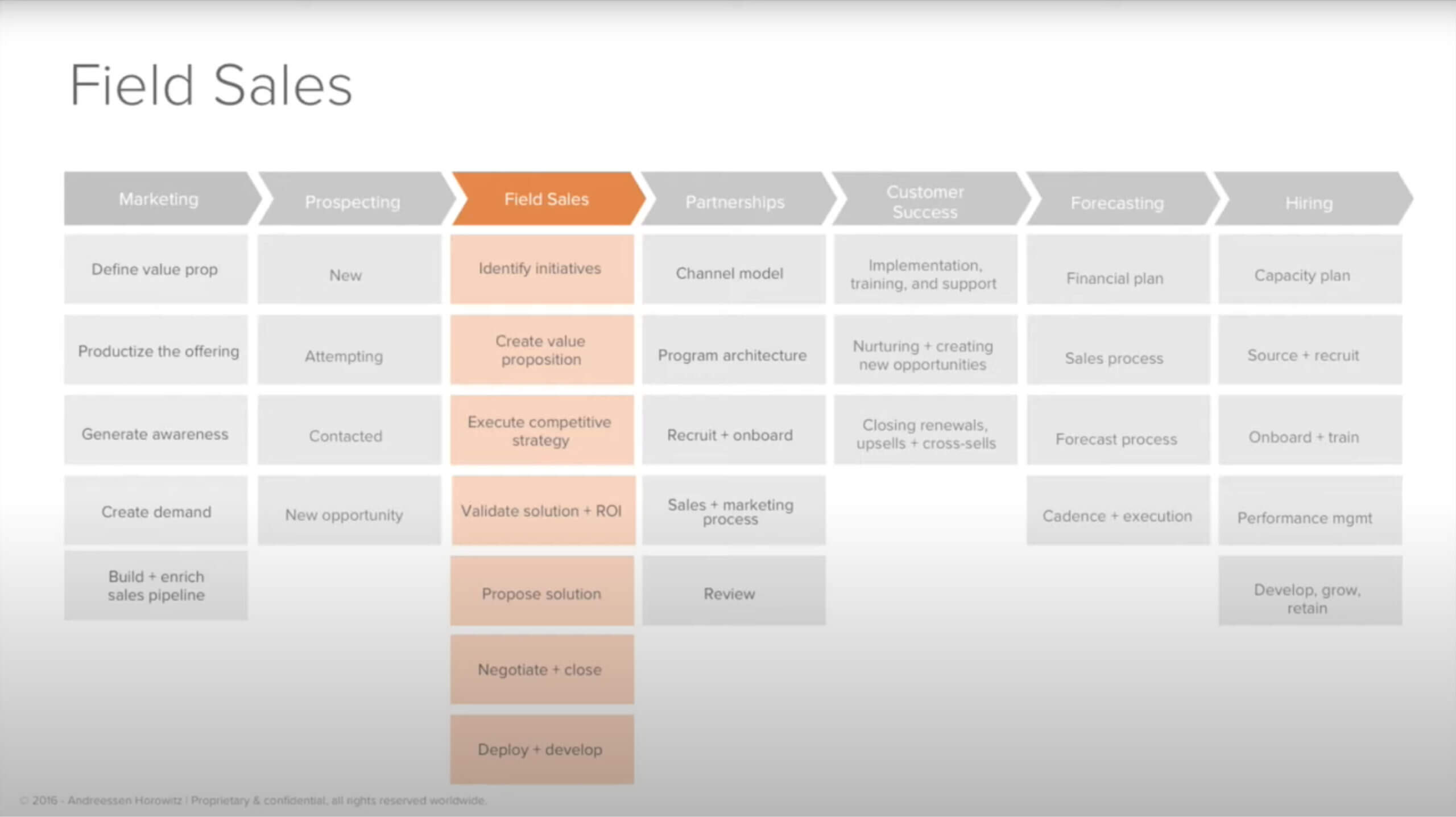

We’re running a sales and marketing motion for our portfolio companies to help them connect to the largest, most complex buyers across the Global 2000, the Fortune 500, and the largest government agencies. We teach a go-to-market boot camp that allows our portfolio companies to see what their go-to-market organization could look like at scale and to help them accelerate their time-to-market as they build out processes, people, and structures. The components of the boot camp really span the go-to-market gamut, but today we’re going to drill down into field sales.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Top down, bottom up, and hybrid sales approaches

TABLE OF CONTENTS

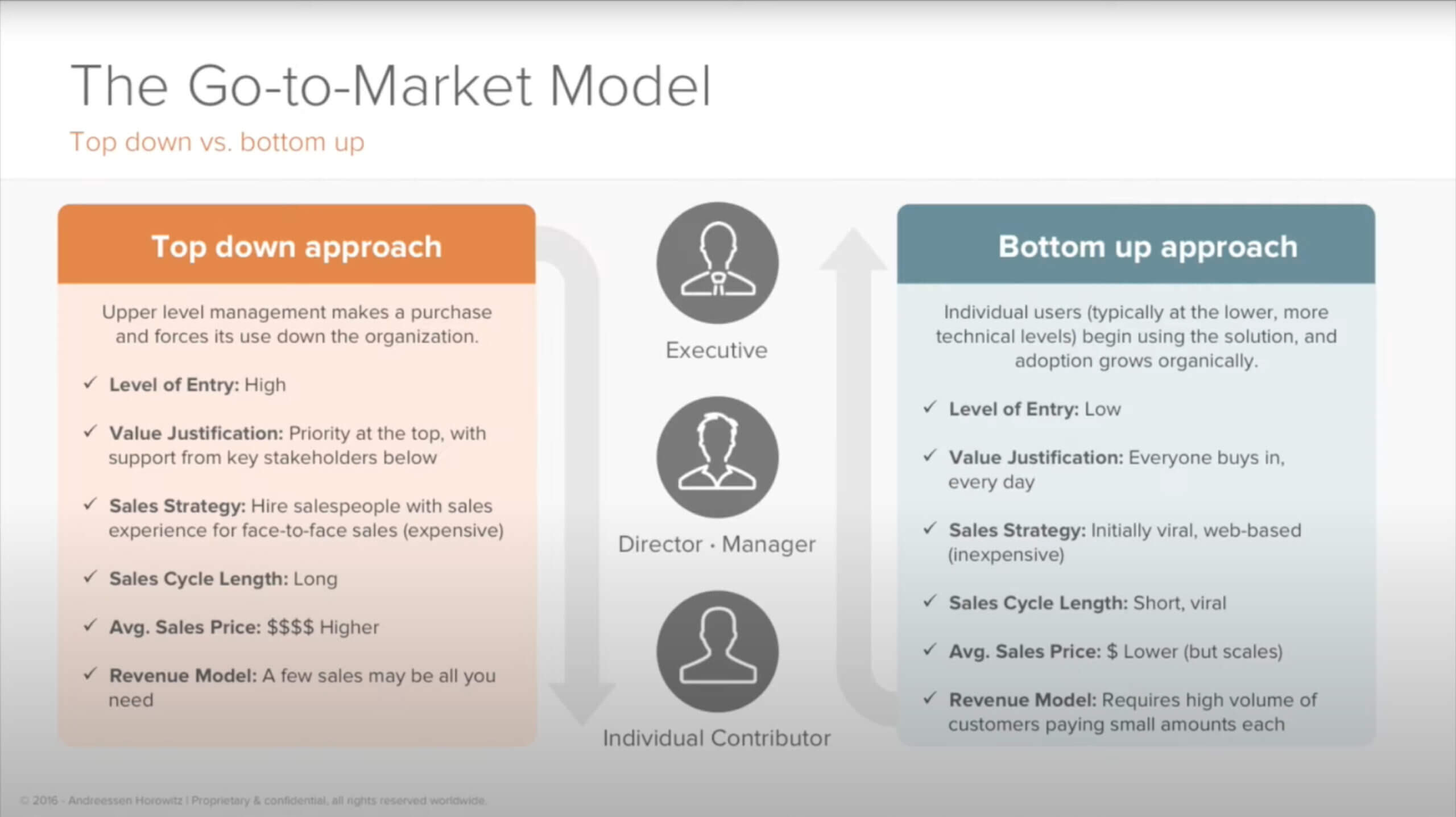

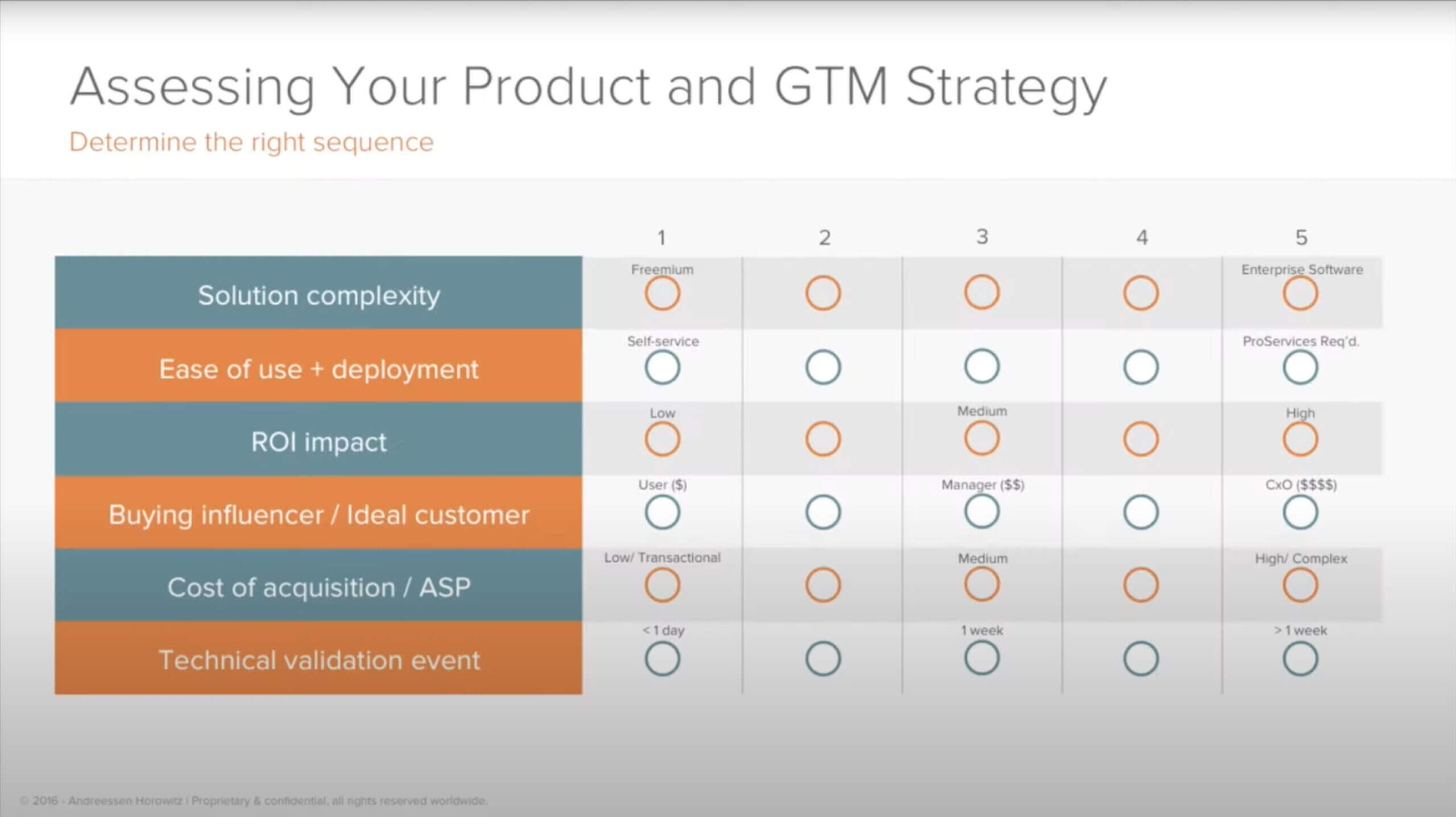

If we think about a top-down sales approach, we may start with an outside direct sales force versus a bottom-up approach. This depends on your product readiness. Is it a freemium to premium model? Or is this an open source product where we will definitely start with a bottom up motion and layer in top down later? Who are the initial personas you’re targeting? Are they executives? Are they VPs, directors, and managers? Or are they the product users?

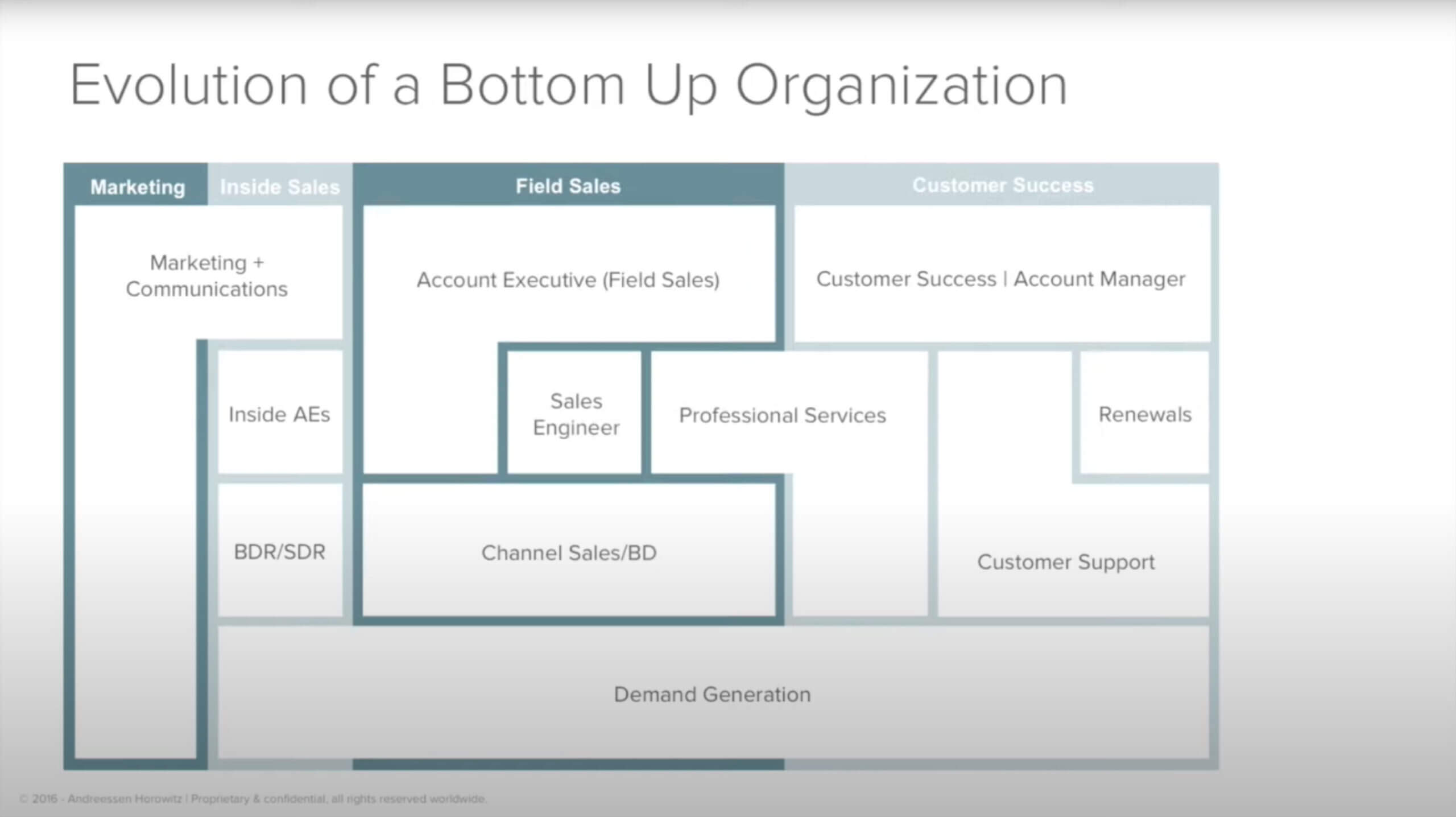

If you’re going to start with a user-focused bottoms up approach—land and expand or freemium to premium—the progression of building out the layers of your sales and marketing organization may look something like this: Start with demand gen, SDRs, and inside sellers, then beef up marketing, customer success, and support as things mature.

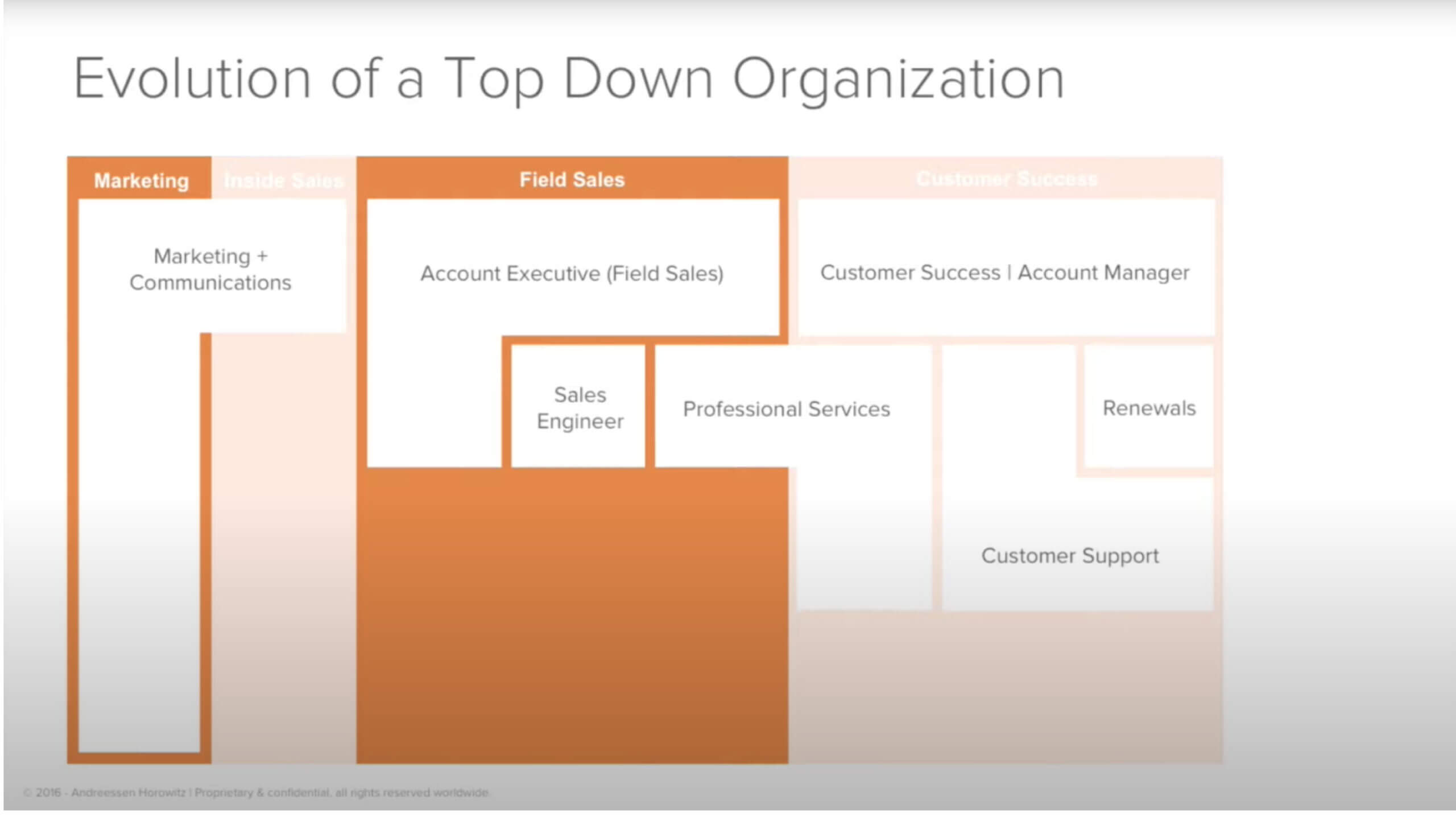

After we’ve expanded and gotten toeholds in the organization, layer in outside-in territory field account teams. In some cases, we may start with outside direct salespeople who can walk the halls of these big Fortune 500/Global 2000 companies, and government agencies. The sales process is going to be a lot more complex and we’ll be selling things like architecture—so we need to involve senior salespeople.

We’ll have to put sales engineers and professional services in place pretty quickly and ramp up marketing lead gen efforts for the field sales force. Once we nail down those first customers, we’ll build out customer success teams and renewals, then backfill with an inside team to augment and supplement the field sales organization.

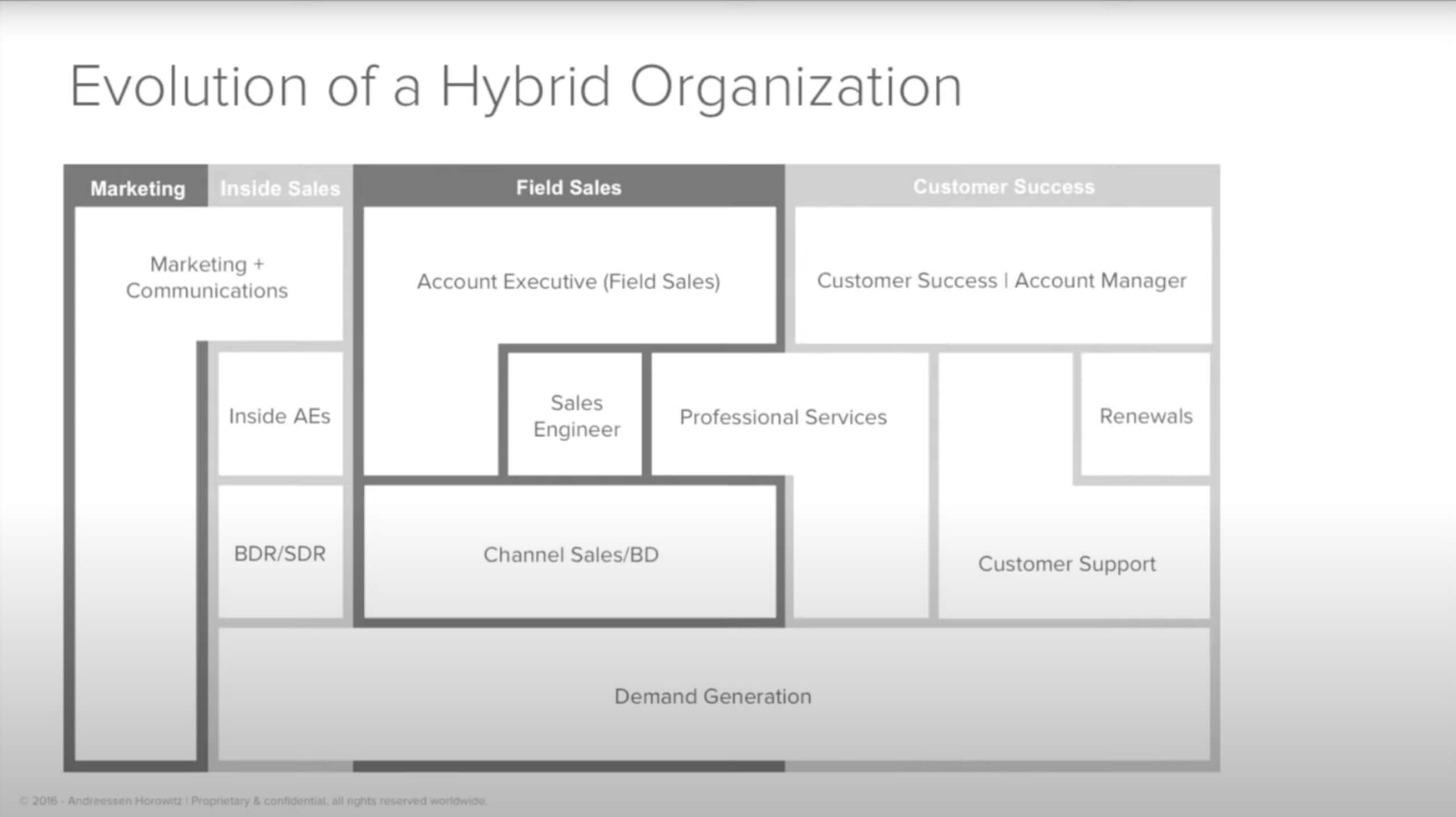

In some cases, the product may fit across the board, so the process can be more concurrent than sequential.

The point I want to make here is this: When we go down one of these three paths and we don’t know our next steps, we might wait too long to implement because we don’t recognize what’s needed.

To recap, if you’re a senior executive or founder in a high-growth company or startup, ask yourself these questions:

- How complex is my solution?

- How easy is it to use and deploy, particularly initially?

- How big of a business case or ROI impact will it have?

- Who are my buying personas?

- Should I start bottom-up?

- Will our sales process start with senior level execs?

- Am I in a cross-functional situation?

- What is my expected deal size, both initially and moving forward?

- What kind of technical validation events will I have to go through?

The purpose of these questions is to set the tone upfront.

Anatomy of field sales

On that note, today we’re going to do a deep dive into the outside direct-in-territory field sales organization. A lot of what we’ll talk about applies to inside sellers, such as an outbound team closing smaller transactions via phone. To really understand how to sell to large and complex organizations, you have to have field sales teams in the territory who are familiar with and have experience selling to these big companies.

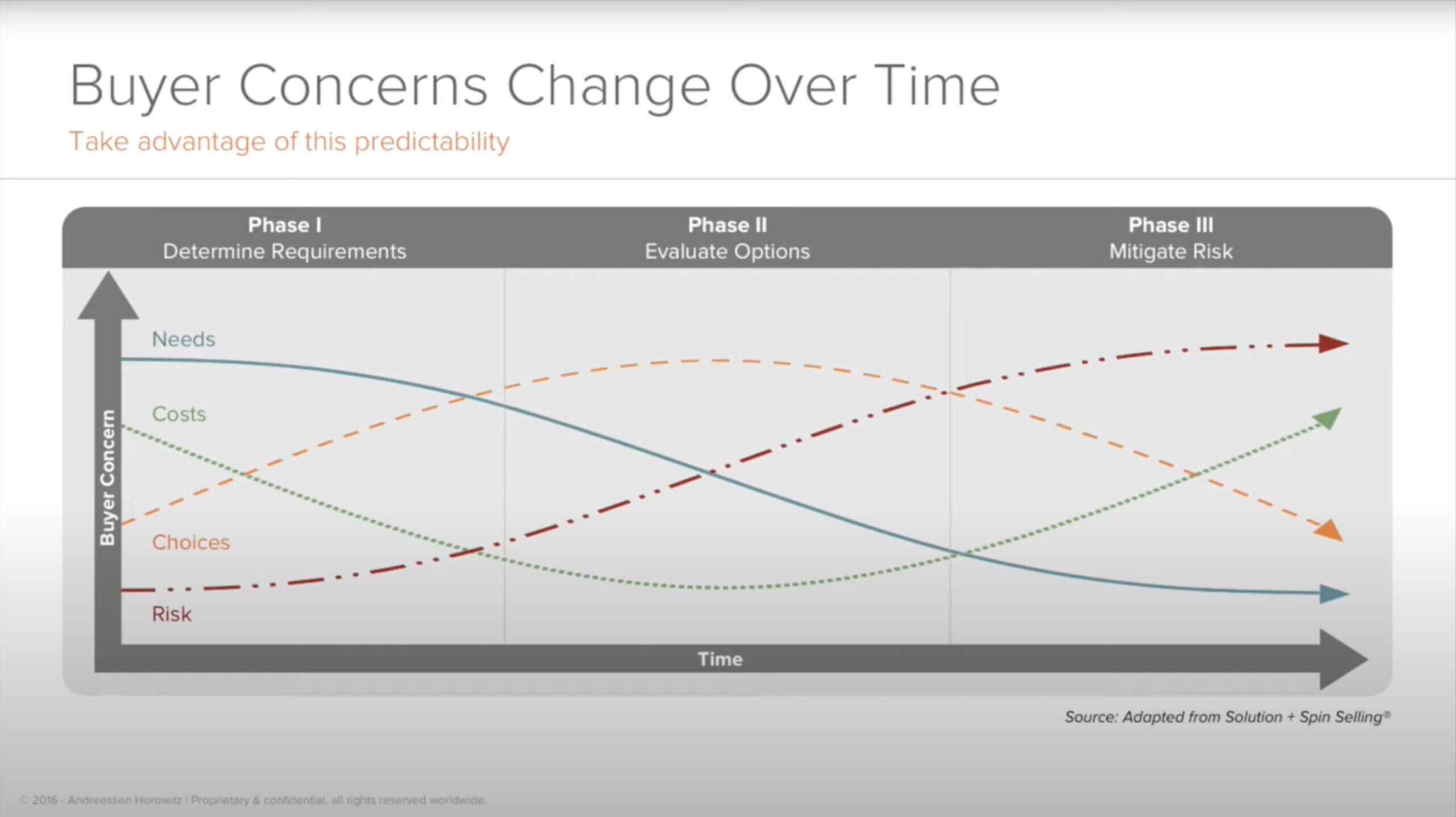

The buyer’s journey

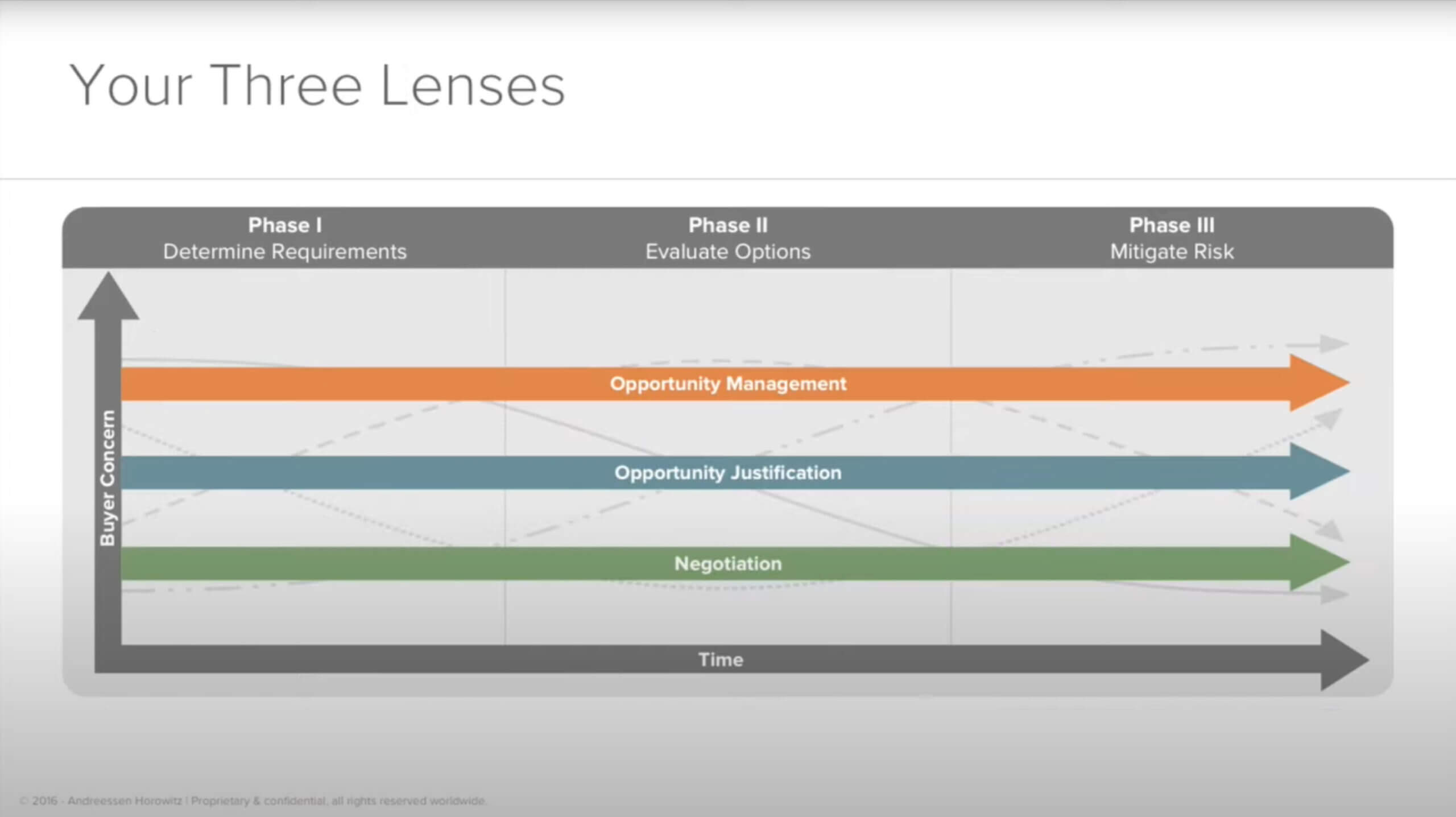

Let’s put ourselves in the buyer’s shoes and ask ourselves three questions: Why should I do anything different from what I’m doing now? Why should I choose you versus the competition? Why now? Then, let’s take it down to the next level to understand how the buyers’ concerns are going to change over time.

Moving from left to right, when we are determining requirements the buyer’s initial concerns will primarily be around needs and cost, while they are less concerned with the number and depth of choices and risk. There’s really no risk in the early stages for senior executives or even users at these big companies because they still haven’t answered question one, which is, “why should I do anything?” However, it’s important to understand the whole process from a buyer’s perspective.

Once we answer the first question, we move into the evaluation stage where we’re answering the buyer’s next question, which is, “Why should I choose you over the competition, which includes doing nothing?” During the evaluation stage, needs and costs go down while choices rise to the top. During phase 3 we’re answering the question, “Why now?” Choices go down, cost goes back up, and risk increases as the buyer gets closer to pulling the trigger.

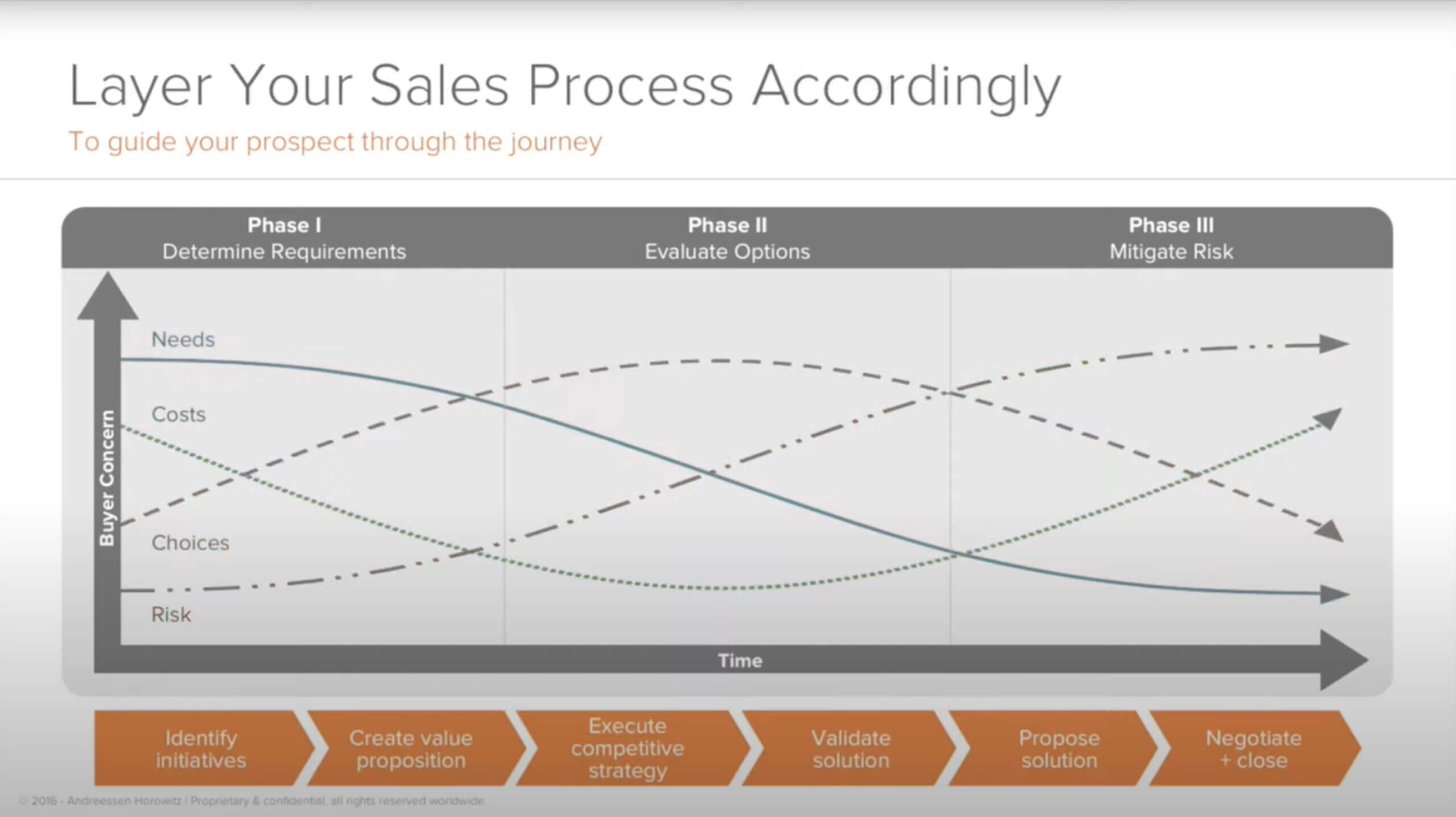

Mapping your sales process to the buyer’s journey

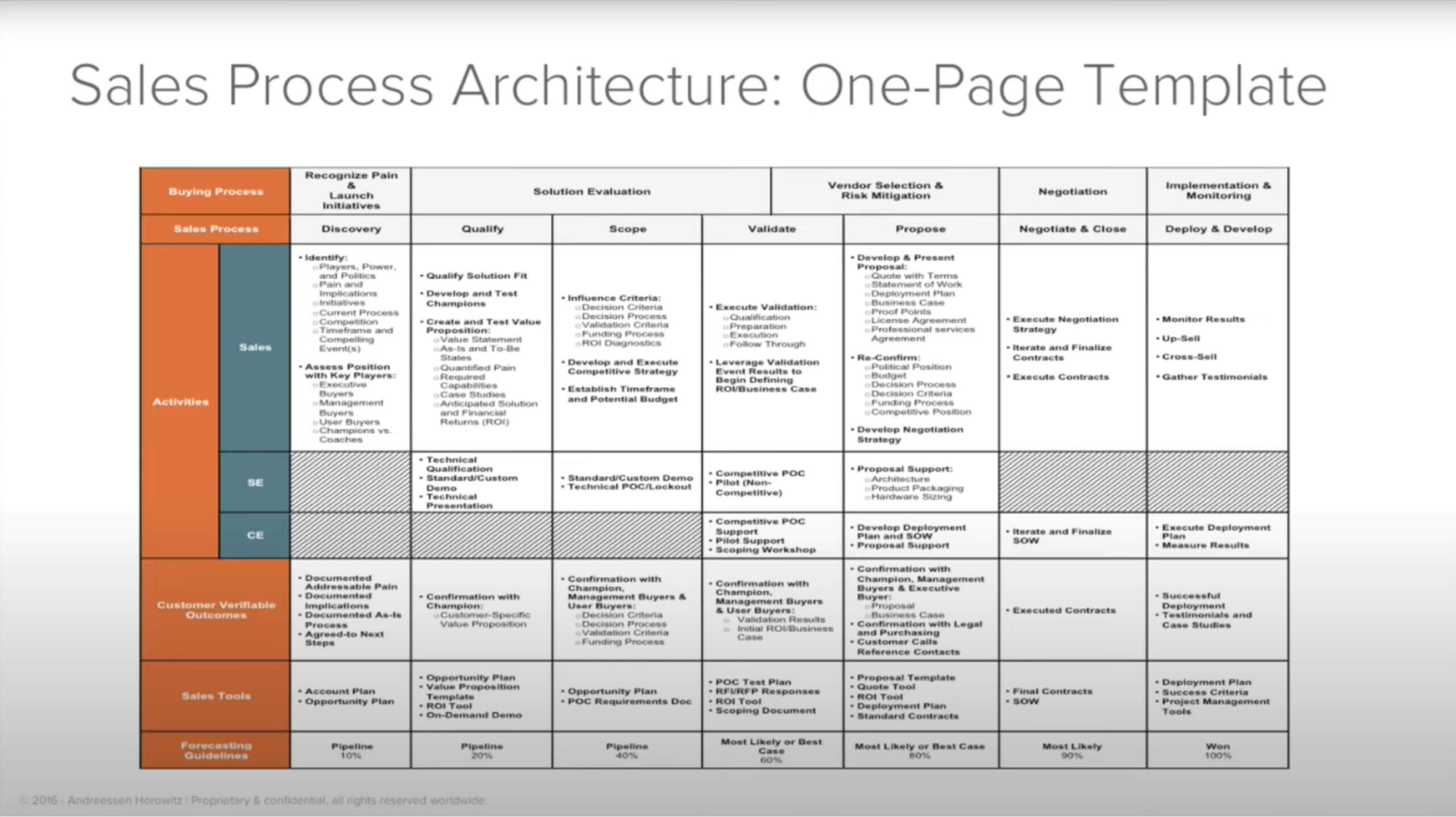

Next we want to overlay our sales process onto the buying process. Everyone’s sales process is going to be different, but it should start by answering the three high-level questions we discussed above. Our go-to-market engine is there to help that prospect or buyer through those three questions.

When we’re building out this sales process we also have to think about how we’re going to manage the opportunity. How am I going to justify the opportunity? How am I going to negotiate? And not just at the end, but negotiate through all the stages and gates that we step through on this buying journey.

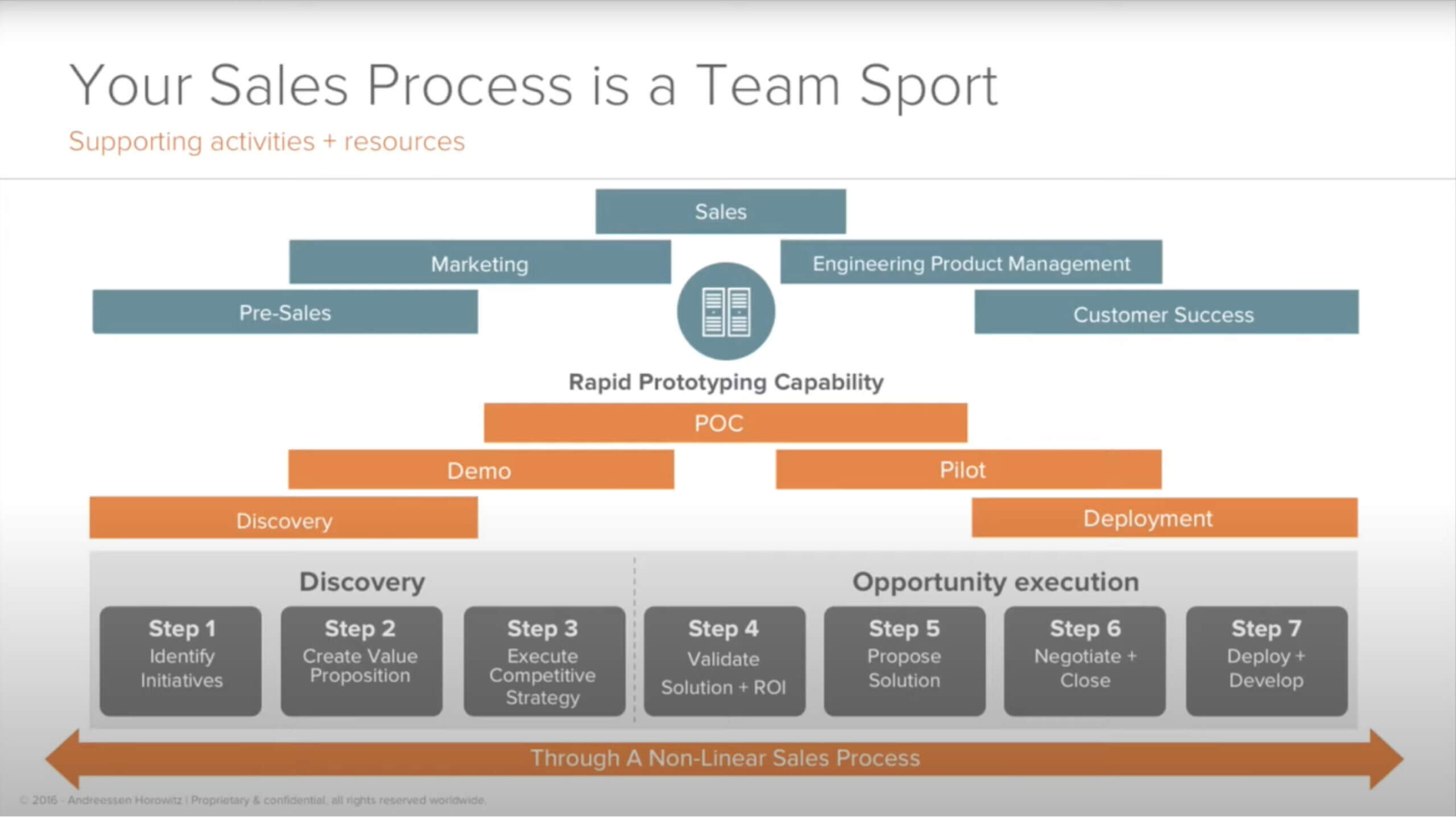

From qualification to execution

Beyond asking our three questions, we should look at the process as three big buckets. The first bucket is discovery and qualification. Once we get a little bit deeper—early on or midway through the “why you over the competition?” question—we move into opportunity execution. A lot of this sales process is non-linear. We also need to think about the technical skills and pre-sales engineering support we need, resources for a potential training and deployment, as well as the kinds of events we will need to prove our solution. Again, this process might start out using open source and then move up the solutions stack to security and scalability, all the way to freemium to premium-type models.

We also need to think about the other groups in our go-to-market organization that will impact this process, including marketing to engineering, product management, as well as customer success. It’s not just about sales. In fact, the individual sales contributor and sales management is in a lot of cases the quarterback, and we want to make sure we’re getting the right people in the right place at the right time to advance that process and help that prospect through that buying journey.

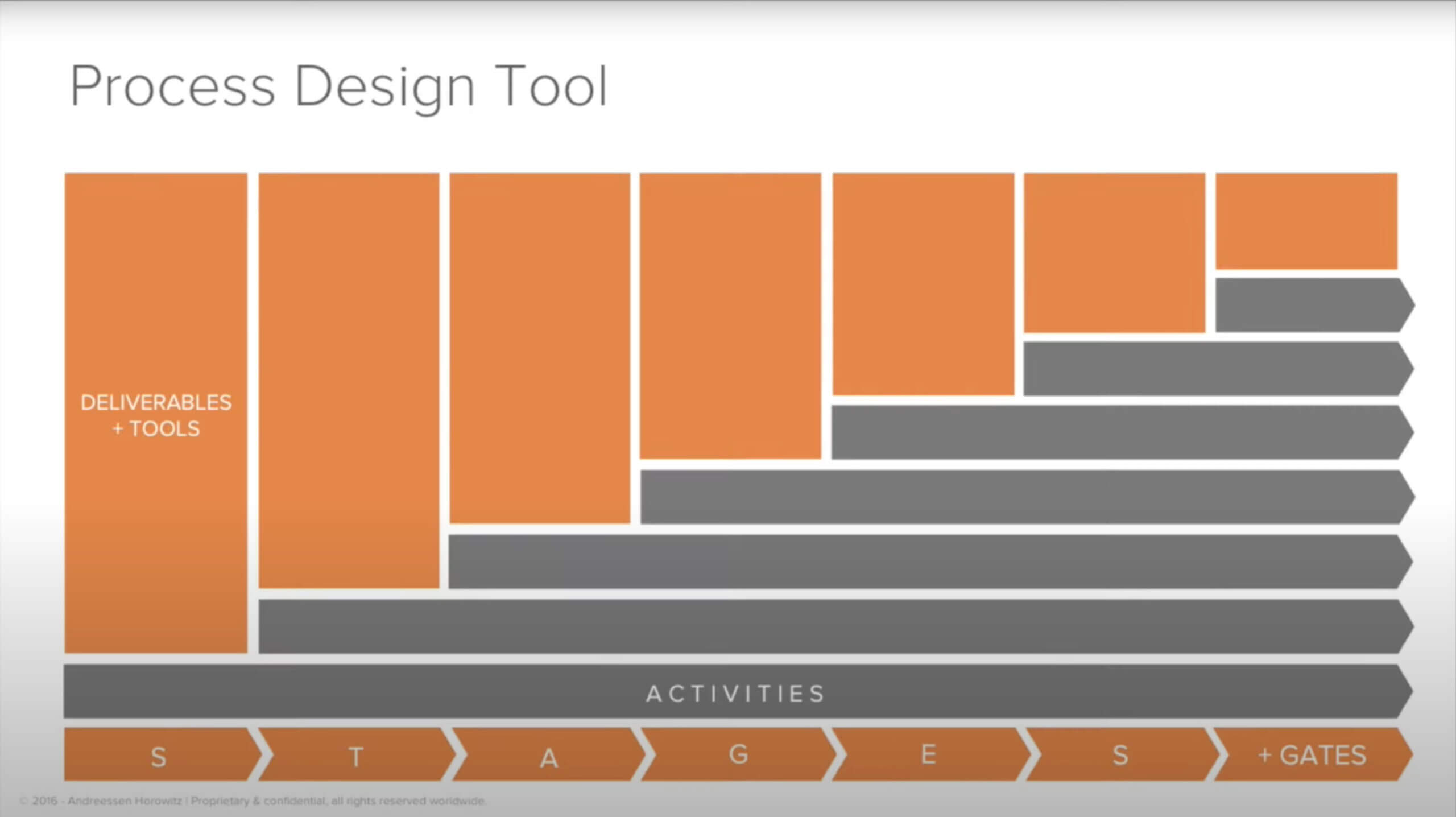

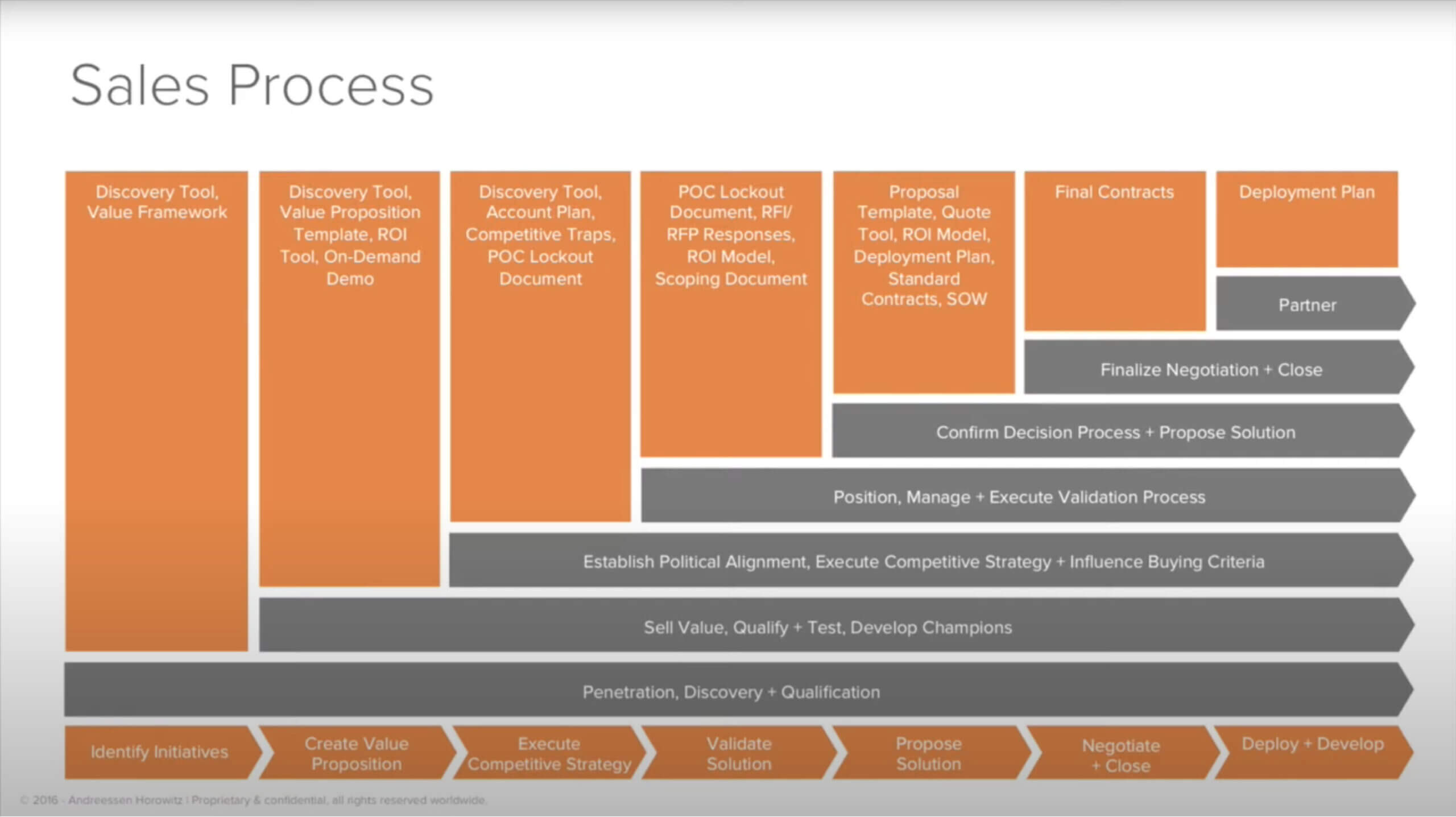

The slide below is designed to help make an abstract process a little more concrete. At the bottom, there are stages and gates, and above those in gray is a potential template where you can layer in your activities throughout the entire buying journey for our customers. North and south are deliverables that we can use as a sales and marketing organization to determine if we’ve got customer buy-in—because we need customer buy-in at every step before we can move on to the next stage. This tool allows us to recognize where we’re at with the prospect in a mutually agreed upon process and make sure we are spending the right amount of resources and time on the customer.

Let’s dive a little deeper and fill all these buckets in, including the stages and gates, the activities going left to right in gray, the deliverables going north and south, and then overlay the entire journey with our three questions. This is the journey that will help move us to trusted advisor status with our prospect and turn that prospect into a customer.

Communicating value versus creating value

Let’s step back and address the misconception that the purpose of a sales force is to communicate value. When we’re in a startup or high growth situation and we’re selling something that’s completely new and differentiated that might not be easily recognized early on, the more we dig in and understand what’s going on in the prospective customer’s world, the easier it’s going to be for us to articulate our value proposition and help them through this process.

We want to start by really understanding the customer’s business and their higher level initiatives. This avoids running right to the solution before we have that context because, at the end of the day, we’re not really communicating or recognizing value until we’ve got that distinct understanding of what’s going on in our prospect or customer’s world. The true value of a sales force is to create new value for customers, and this kind of selling requires a different mindset. That’s only going to happen if we’ve got a deep understanding of what a prospect’s initiatives are and how we can overlay those often unrecognized needs with our selling process.

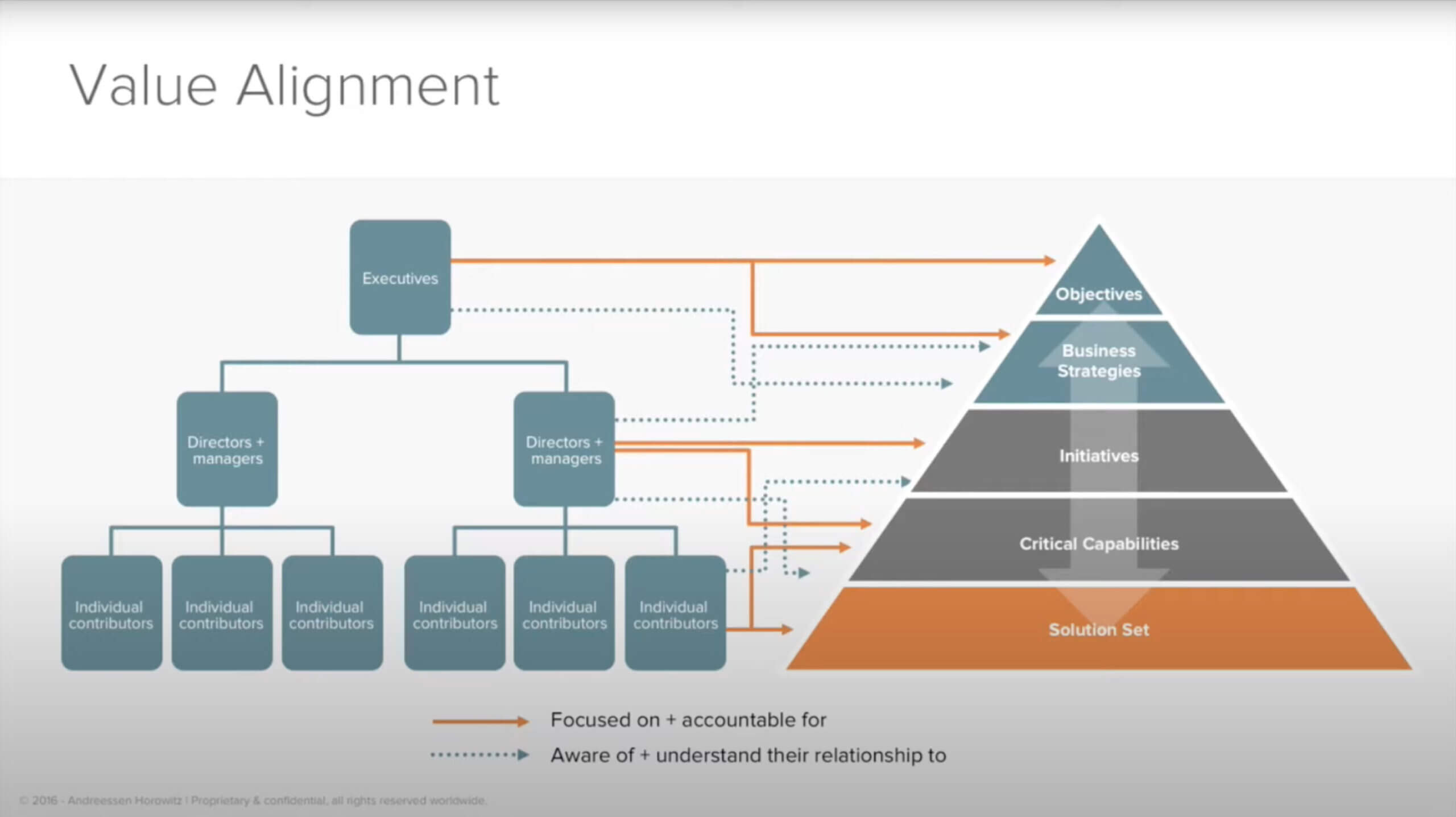

At a high level, let’s start off thinking about what’s on executives’ minds and what’s going on across these big organizations with VPs, directors, managers, individuals, and teams of individuals. They all are focused on and accountable for different things. If I think about an executive, they’re focused on corporate objectives and strategies. They’re aware of and understand the relationship initiatives and, in some cases, all the way down to critical capabilities.

If we think bottom-up from the solution set, the people who are actually using and deploying new technology and new techniques will be focused on and accountable for more of the technical feature functions of what we’re selling and an in-depth understanding of critical capabilities. They do not have as sharp of a focus on the business strategies or initiatives, but they’ll definitely be focused on and accountable for them.

The big value of a really high-end go-to-market motion and sales force, particularly in the field, is that in-depth knowledge of how their prospects and customers actually work, then stepping across that sales process as the quarterback to actually help their customers get things done internally. That deep knowledge of how these companies work can be a very valuable tool.

Developing the value framework

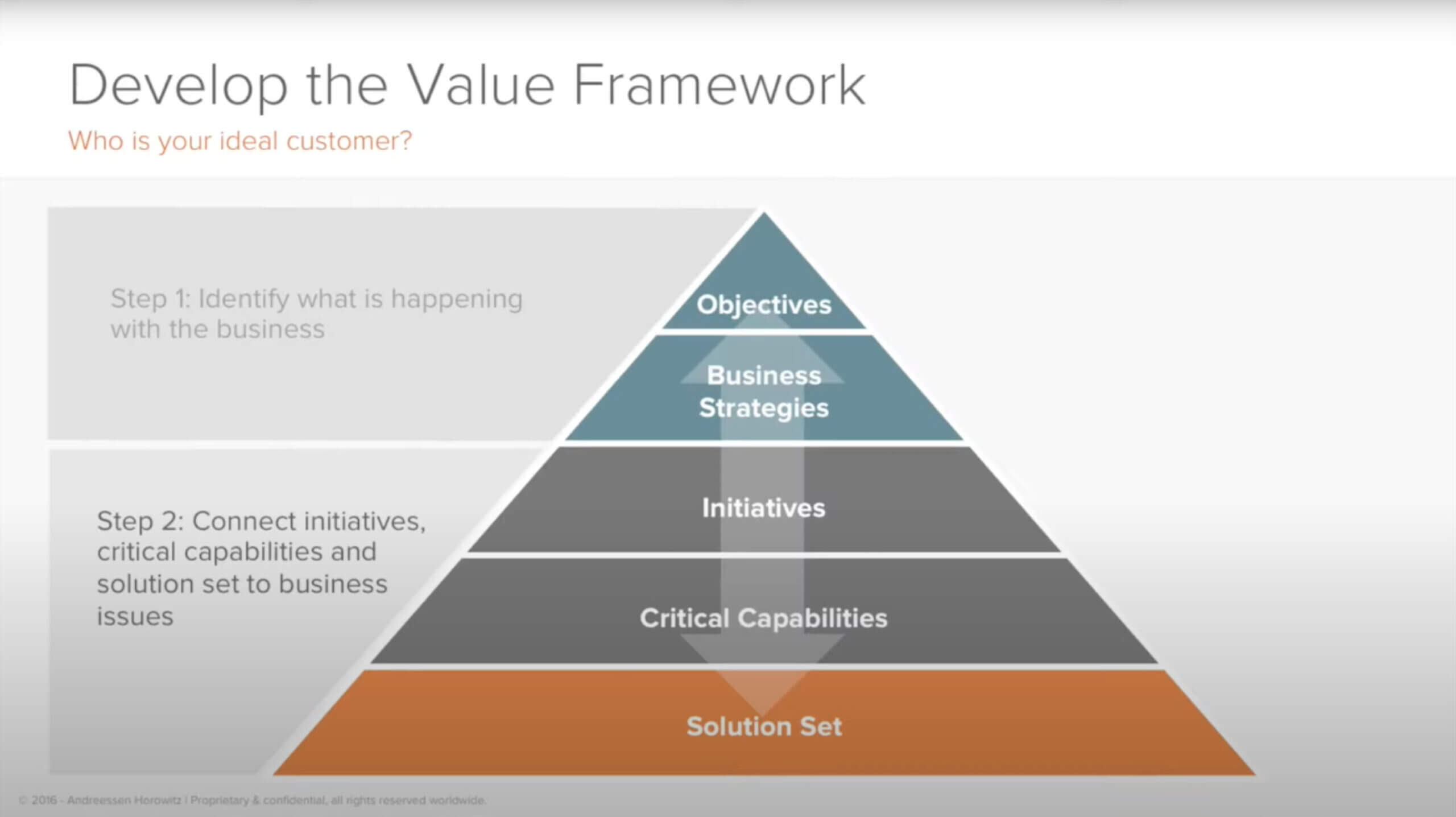

Let’s back things up a little bit and talk about what is a business objective and initiative, what executives are focused on, what our ideal customers are focused on, and the problems we can help solve. We need these answers pretty early on.

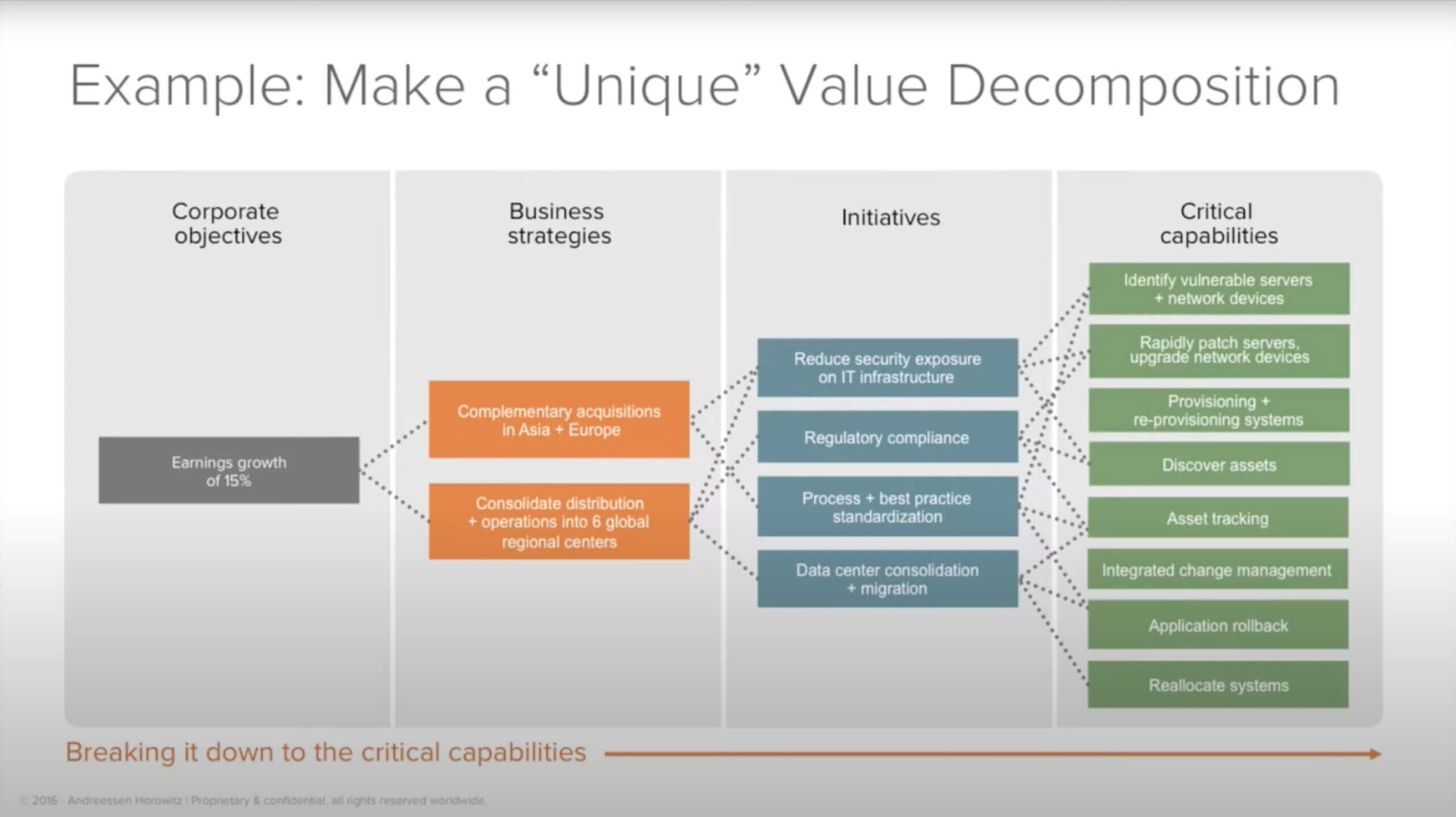

Corporate objectives are almost always for profit and revenue and to increase the company’s owner and shareholder value. Every company has different business strategies that drive different objectives. Some companies may be more product-focused and are known more for their product innovation versus operational excellence or customer intimacy. It’s important to understand that early on in a selling or marketing situation.

When we’re building out a value framework we need to connect how business strategies turn into business and technology initiatives. That is the secret sauce of a high-end, precise go-to-market. An initiative is really the actionable plan that supports the strategy, so we need to document and articulate that for whatever we’re going to market with down to customer verticals and their industries. Initiatives really map up to and drive corporate objectives. Critical capabilities are the must-haves that support the initiatives. They’re going to look like what you would normally think of as features and functions in your solution. Down below is the solution set, which are features and functions. A lot of early-stage and even later-stage companies and their sales organizations start down at the solution set and work their way up.

One of the most effective ways of up-leveling a sales organization is to get them to step back and provide them with the tools and deliverables to show how everything fits together. One way of gaining that understanding is to put this all together yourself.

If I start from the top down and look at my typical customer, I really begin to understand this company’s business and how an investment in my technology would map up to higher level initiatives. One of the most common things that happens in enterprise selling, particularly in a startup or high growth situation, is I’m selling something that’s completely new because of a platform shift. It’s a new way of doing things and there’s no recognition that there’s a new way.

During my career, the sales team would often come back and say, “Look, there’s no budget for what we’re selling.” Well, of course, there’s no budget for what I’m selling. They’ve never bought anything like it before. What I need you to do is look for the high-level strategies and initiatives and gain situational awareness via a discovery process to understand the best place to go. We have limited resources, so we need to find the point of the spear from a company or vertical standpoint. We have to segment and target and do a great job of understanding our perfect situation and then recognize that we can help them with that initiative. Then the budget will be there, even if they haven’t budgeted specifically for what we’re selling.

Creating a value proposition

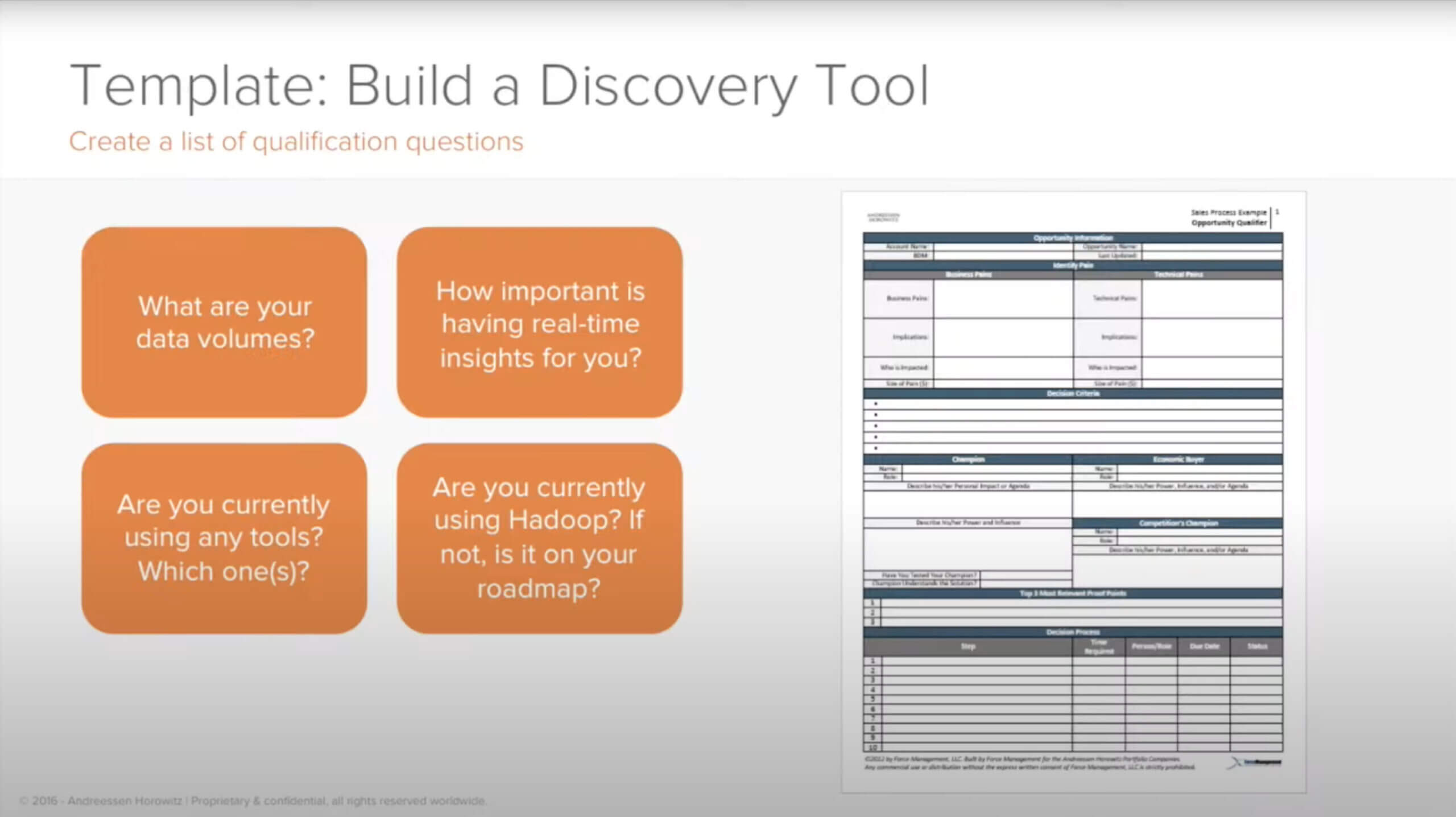

We know we can help them because we’ve asked all the right questions and done the discovery—and we haven’t even talked about our solution. We understand the initiative and the critical capabilities, which are the people, process, and technology that’s required to fulfill that initiative. And that’s before we’ve even talked about what we’re selling.

So, how do we do that? First, put it in writing. Build a discovery tool—the qualification questions across those three big buckets—down to the granular level of the critical capabilities and how that maps up to your solution set. Understand where there’s pain, what you need to do early on, who are the potential competitors, including doing nothing, and gain a 360-degree understanding of our competitive situation. Then we can anticipate if we can tie our technical fit with a financial fit down the line and how that maps our priorities.

Now that we have a good understanding of the customer’s business, is there a fit? We’ve got some depth, which gives us the qualification methodology to get to the next step to say yes, we should pursue this potential opportunity. This tees us up for creating and delivering our value proposition, but even more so, our unique value proposition. Our potential customer is now highly qualified before we’ve ever done what most people think of as selling. We’ve pre-qualified and now we’re testing and developing potential champions and making our value proposition very unique to their strategies, initiatives, and critical capabilities.

Tailor your message to your audience

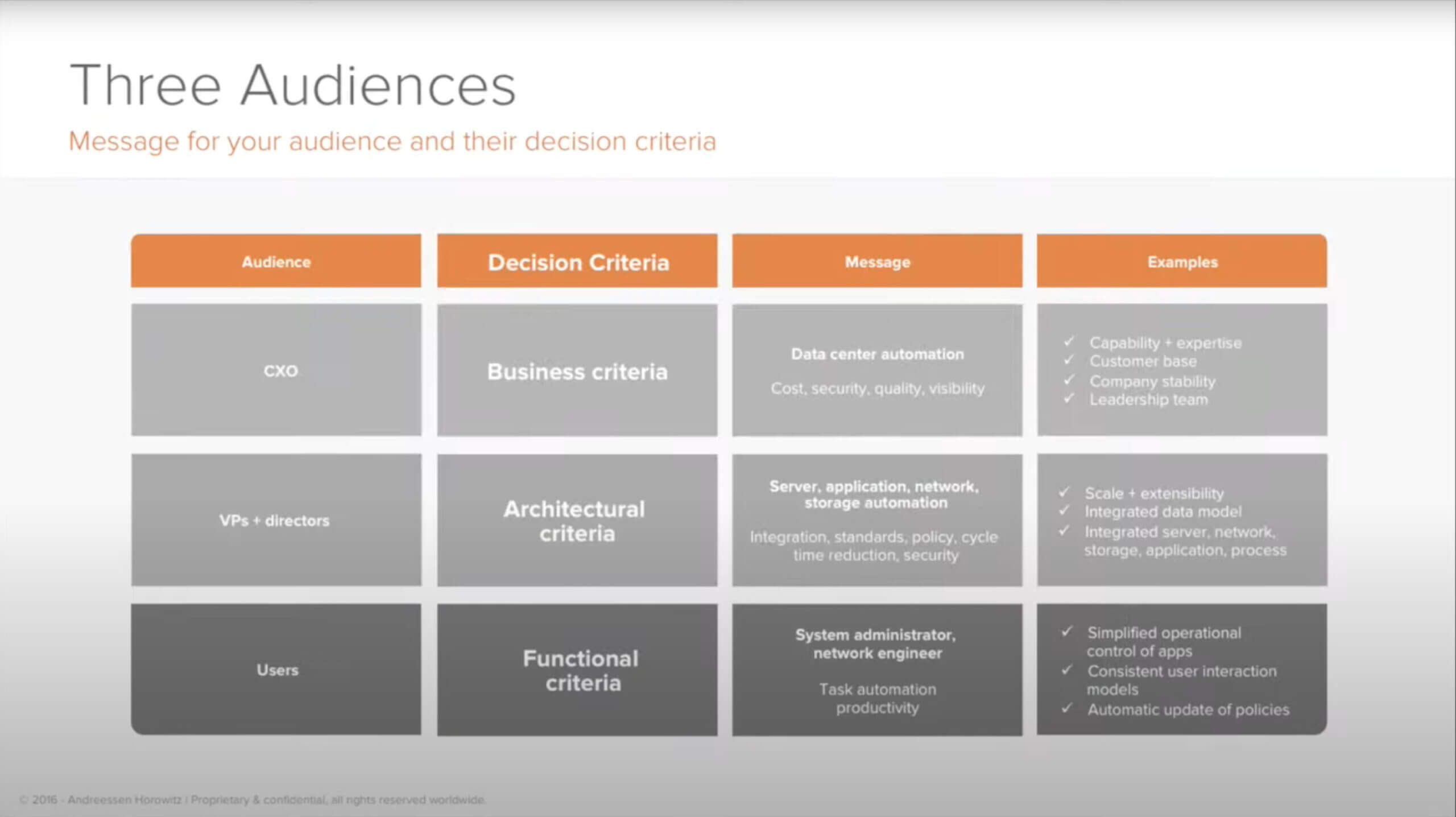

As we step and look at our three personas, one of the things we want to focus on is decision criteria and understand that in all of these situations, if you break a large organization down into threes, CEOs, CXOs, and senior management, all care about high-level strategies and initiatives—it’s really more about business criteria. That’s going to be a little bit different than mid-level management, who are thinking about architecture or scalability and how things are going to work across an organization. At the user management level, they’re looking at feature function criteria.

As we build out our go-to-market and our sales tools and train and develop our people, we need to really define these three lenses and, if we’re doing a bottom-up go-to-market approach and sales process or a top-down approach where we’re layering more in, recognizing that this is going to help us create that unique value proposition.

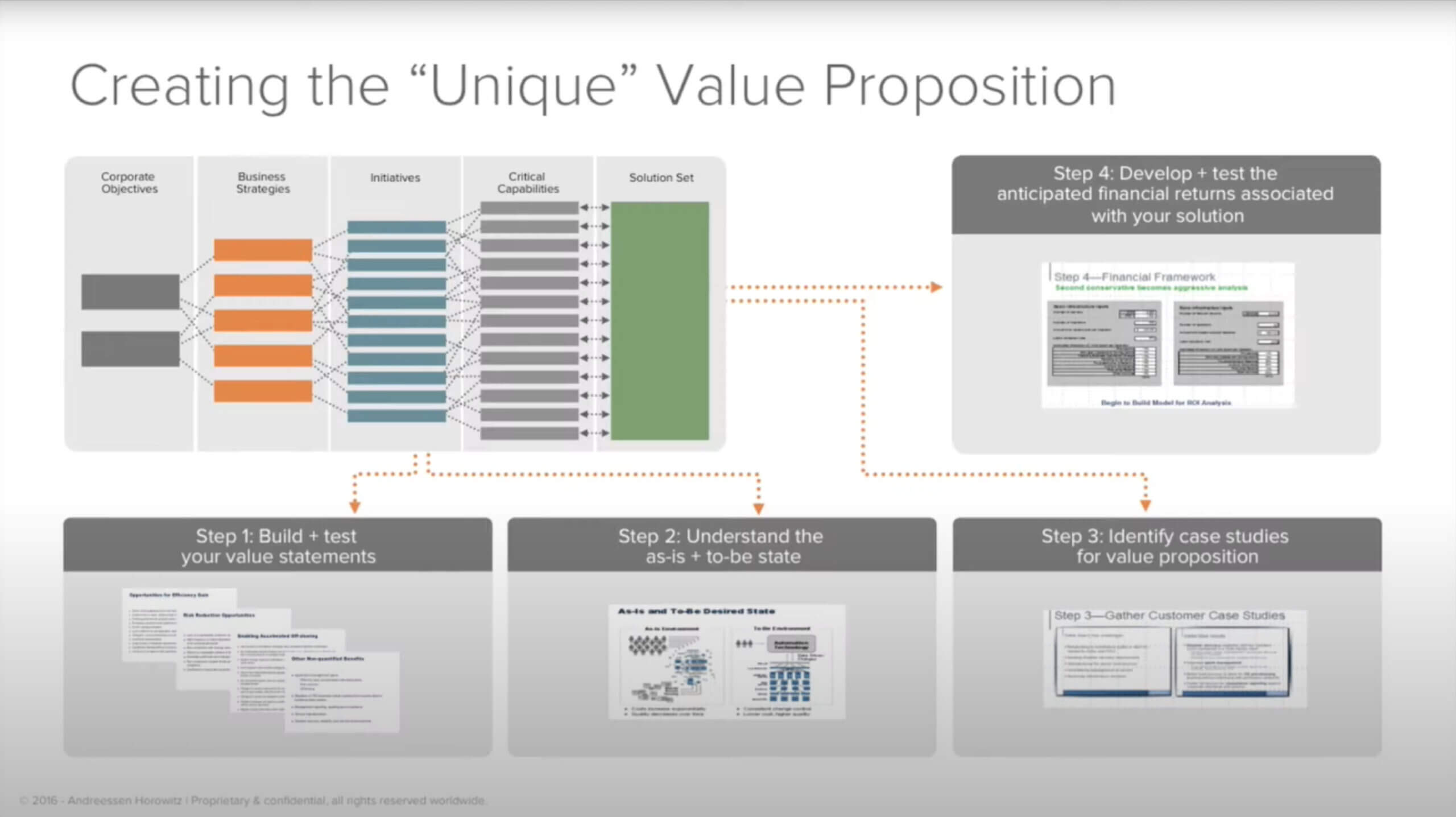

First, we build and test our value statements in these accounts because we’ve done the discovery. Second, we articulate your “as-is” based on what we’ve discovered and then the “to-be” of what we can do for you. Third, we highlight use cases from other customers that show the same type of issues and what we found. Fourth, we can also start to develop and test anticipated technical and financial returns and metrics based on what we can do for them—and that’s really the foundation.

When we tie all this together, we have a unique value decomposition that understands what’s going on in their world coupled with our solution. We can deliver statements that are unique to these big companies in a very effective manner.

You really need to think about the fact that they don’t recognize they’re sick, so let’s help them recognize unrecognized pain and then show them the path where our value proposition can take them. Then we back that up with customer case studies of other people in the industry or personas that are similar to them. Then we’re off to the next phase.

Competitive strategy

Now we’ve answered that question of “why do anything?” Our value proposition is so interesting that they need to evaluate our solution versus what they’re doing now. Then they think about who else is doing similar things to us, and that’s when we move to the second big question: Why should I choose you over the competition? The earlier we position ourselves there, the better.

There’s a tendency for people to not anticipate having to compete and just being happy to move onto the next level. We want to jump out in front of that and insulate ourselves. We want to start establishing political alignment, laying the groundwork for influence in the buying criteria, and potentially executing a competitive strategy. And again, build all those discovery tools, lay competitive traps, and get ready for what I call technical validation event processes, which can come in multiple forms.

How do we do that? I’m a big fan of “The Art of War,” and Sun Tzu. The great general establishes a position where he cannot be defeated and misses no opportunity to exploit the weakness of his enemy. The winning general creates the conditions of victory before beginning the war while the losing general begins the war without knowing how to win it.

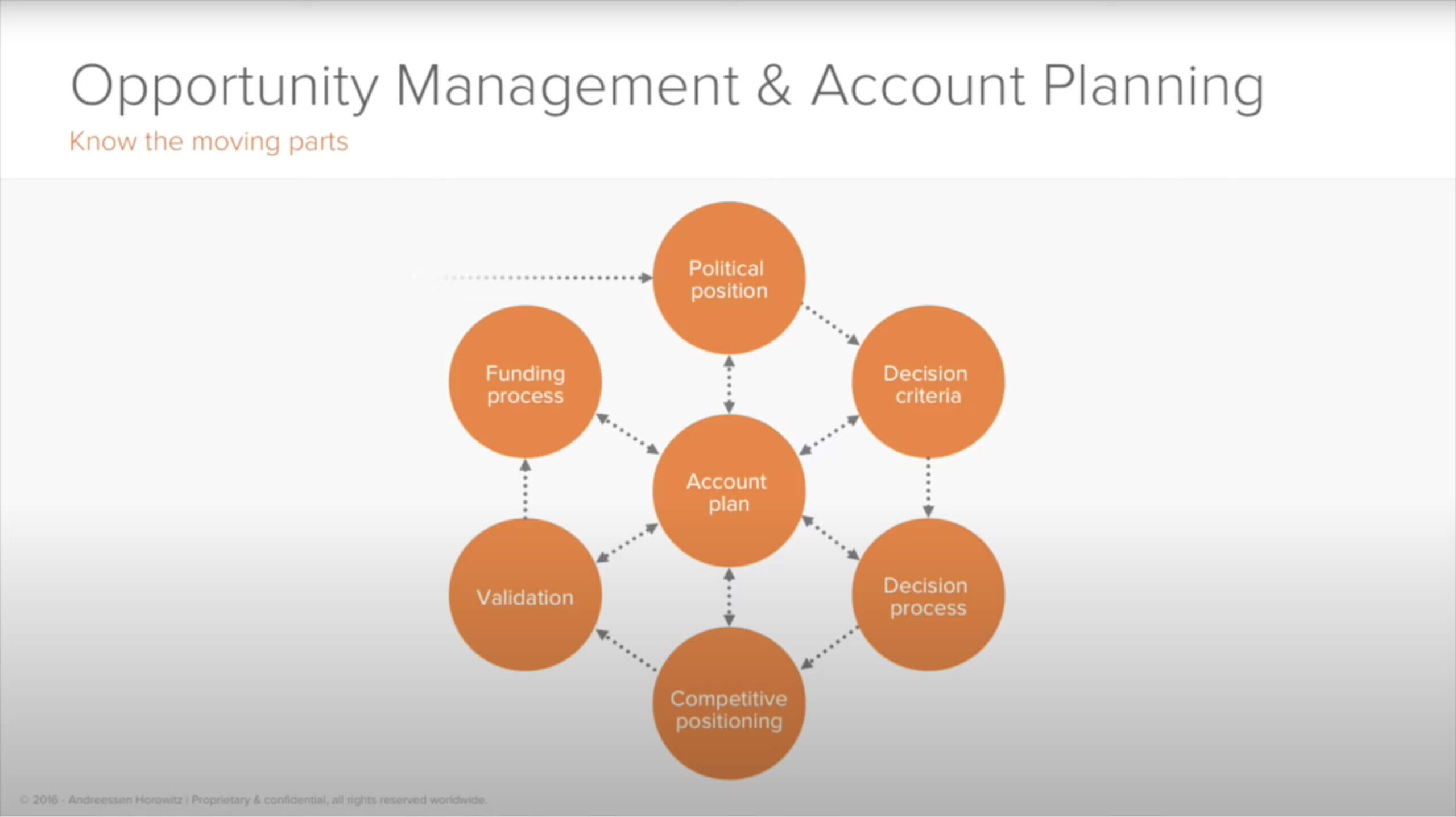

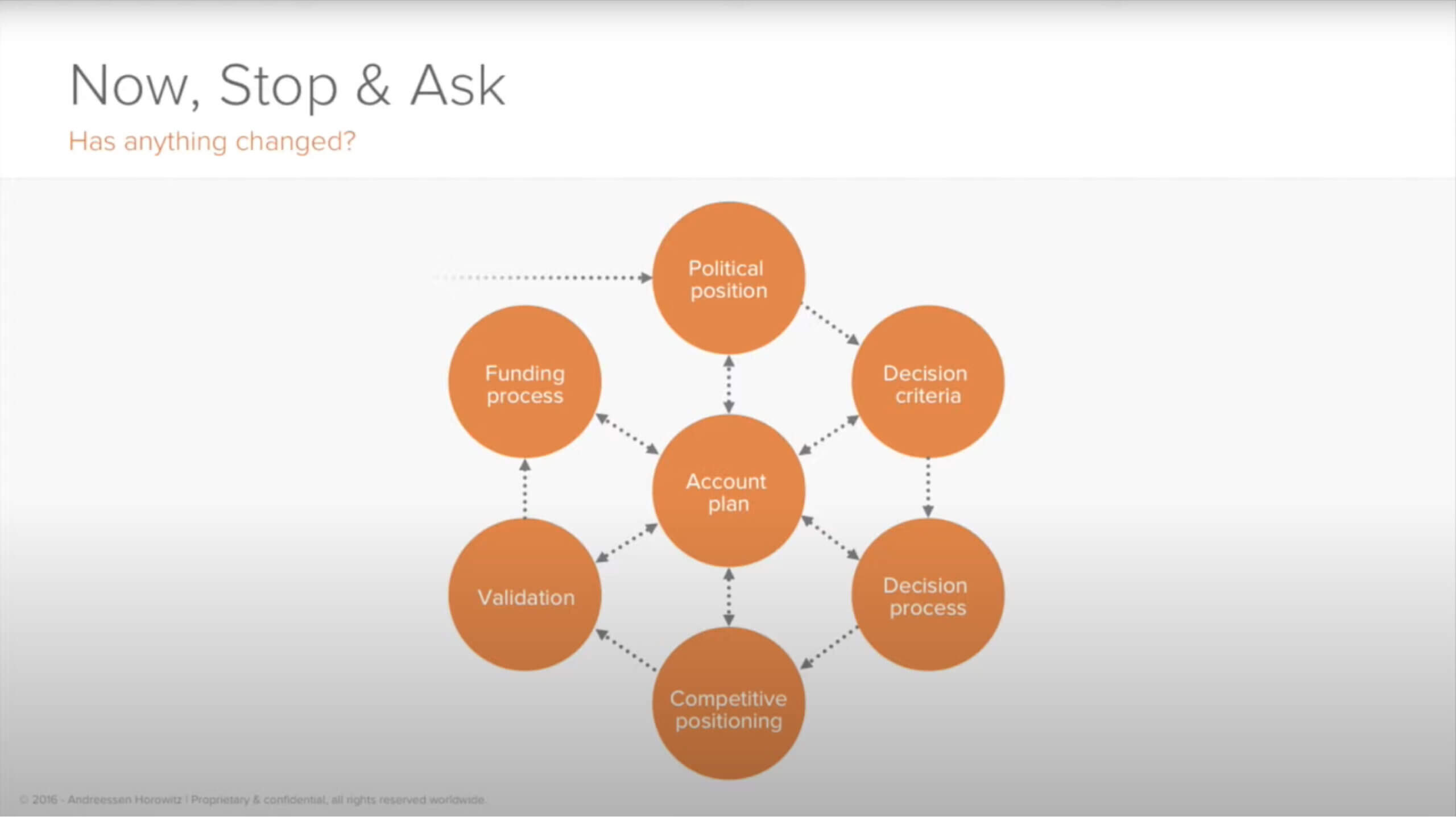

There’s a big tendency of entering into this game and recognizing a little late that you’re already behind. A very granular qualification and competitive depositioning process is crucial. We want to start understanding as early as possible how we do opportunity management and account planning and start laying out all the moving parts, from political positioning to decision criteria and process, teeing up for those validation events and qualifying, and knowing what the funding process will look like because it really does need to be mutually agreed upon.

At a high level, we’re stepping into the fun part where the sparks are going to fly, so we want to look at these prospective accounts from an economic, political, competitive, as well as operational standpoint. Economically, there are a lot of different factors to look at, from industry and vertical, to business strategies and key initiatives, to market position, which is you versus your competition and them versus their competition, and where their financial status is. It’s also important for us to know where they’re at on an adoption curve.

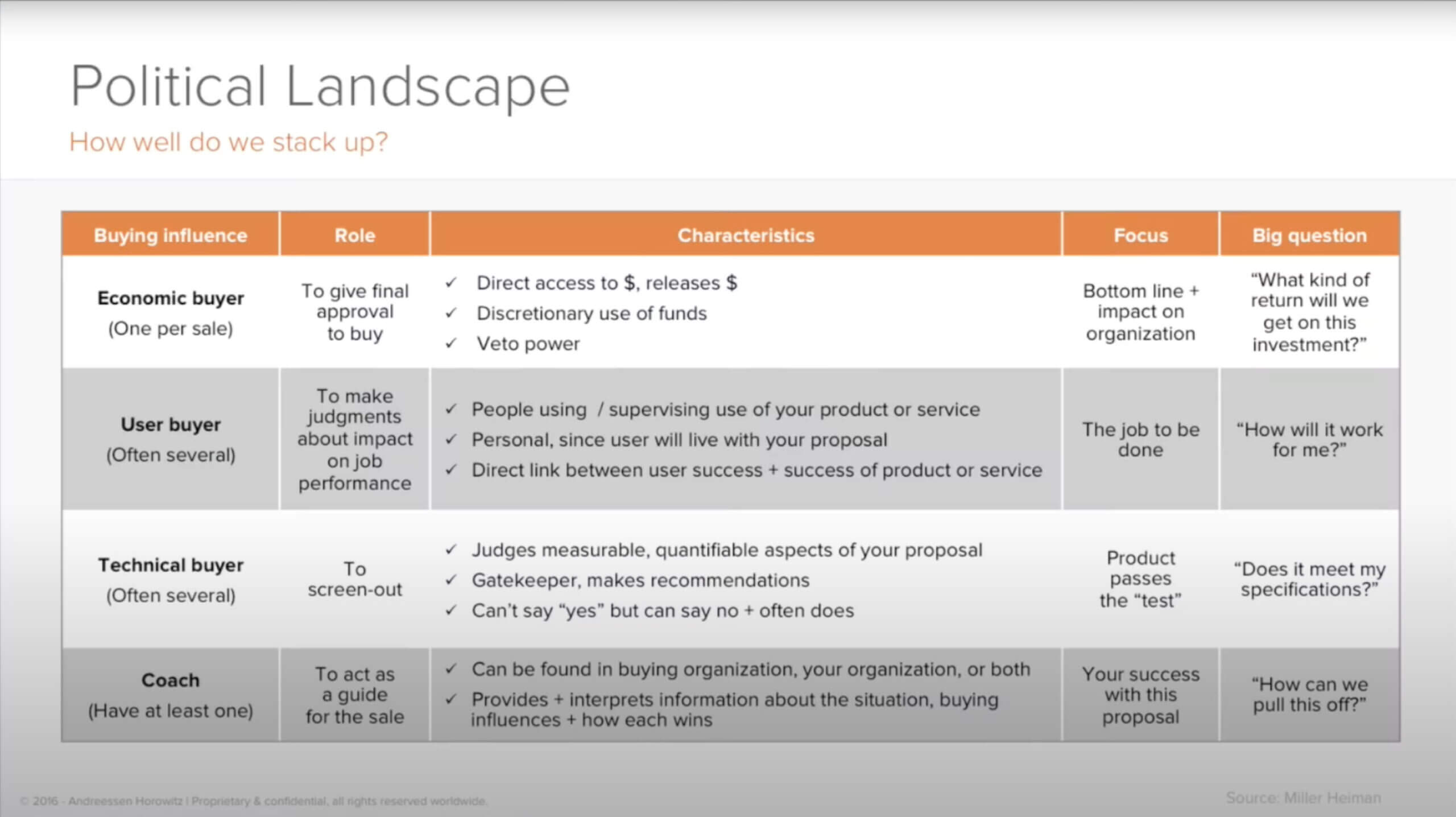

Using the Miller Heiman buying types, we can determine who is our economic buyer, user buyer, and technical buyer, coach, and champions.

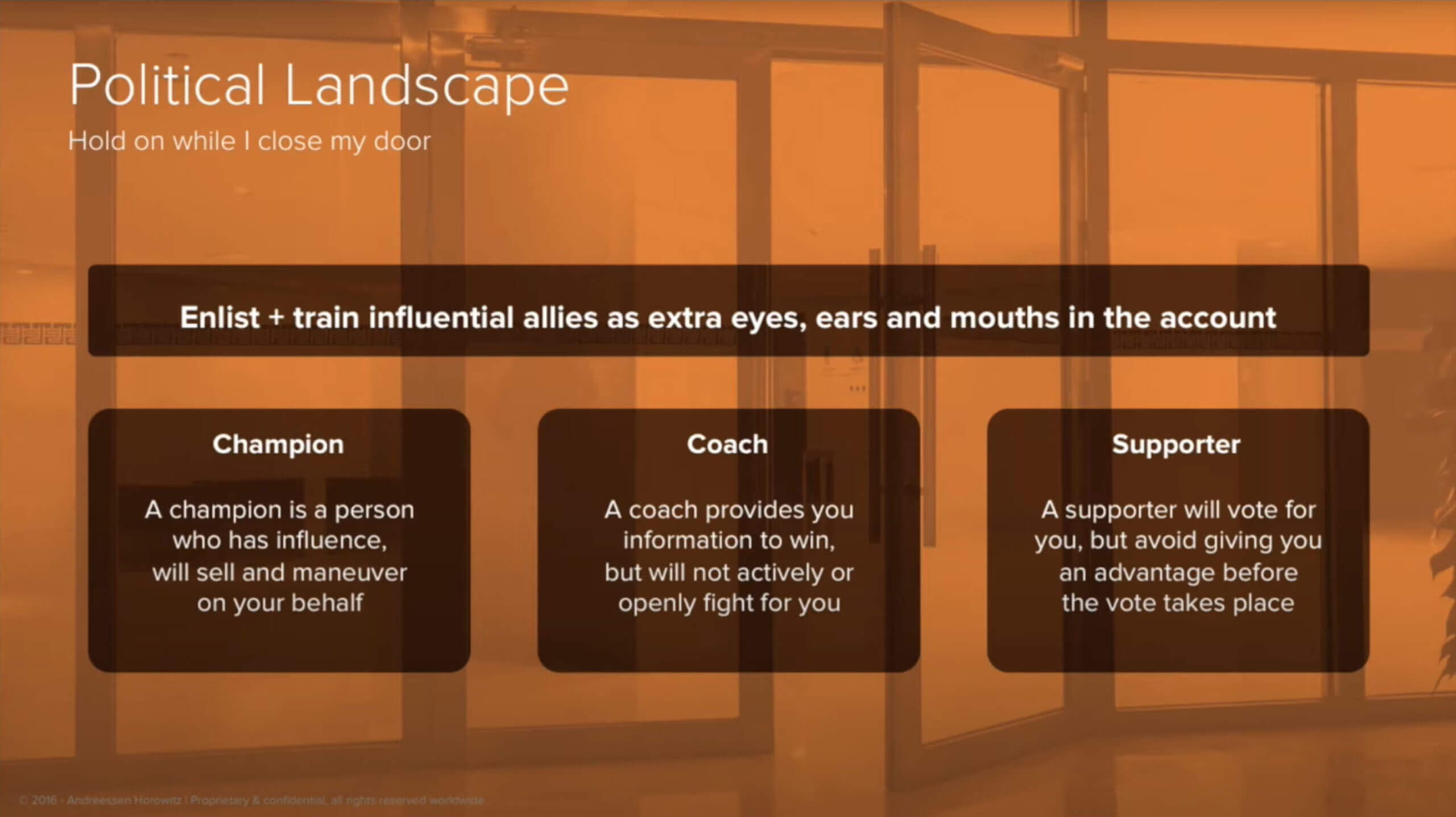

One common problem, particularly in a scaling situation, is determining the difference between a coach, champion, and supporter.

I’ve asked portfolio companies this question over and over back in my operating days as well as today: Do you have a champion? It’s very common that the granular differences between a champion, coach, and a supporter, are not built out. A champion is somebody that if I leave that account or they close the room to have a vote to move to the next level and buy from my company over something else, the champion is actually somebody who has the influence, capability, and desire to sell on my behalf.

A champion is different from a coach who will potentially provide us with some input and tell us how to get things done, but is probably not going to actively fight for us on our behalf. We want a lot of coaches telling us what’s going on because we may have some enemies, but at the end of the day, as we step across this buying process with our prospects, we want to make sure we’re building champions, coaches, and supporters all along this journey. The supporter is somebody we might get a vote from, but a supporter is not going to give us an advantage when that vote takes place. We have to get very granular with champions, coaches, and supporters. This is a continual process that will be baked into our forecasting, inspection, and cadence all along the way. We have to constantly be looking at these opportunities and understanding who’s who.

I would also add—even though I don’t have this in the slide—who are my enemies? It might be just as important to stay close to the enemy or potential enemy. It might be the person who sold the last solutions. I need to know that and continually be looking at that as an individual seller as well as a sales management team.

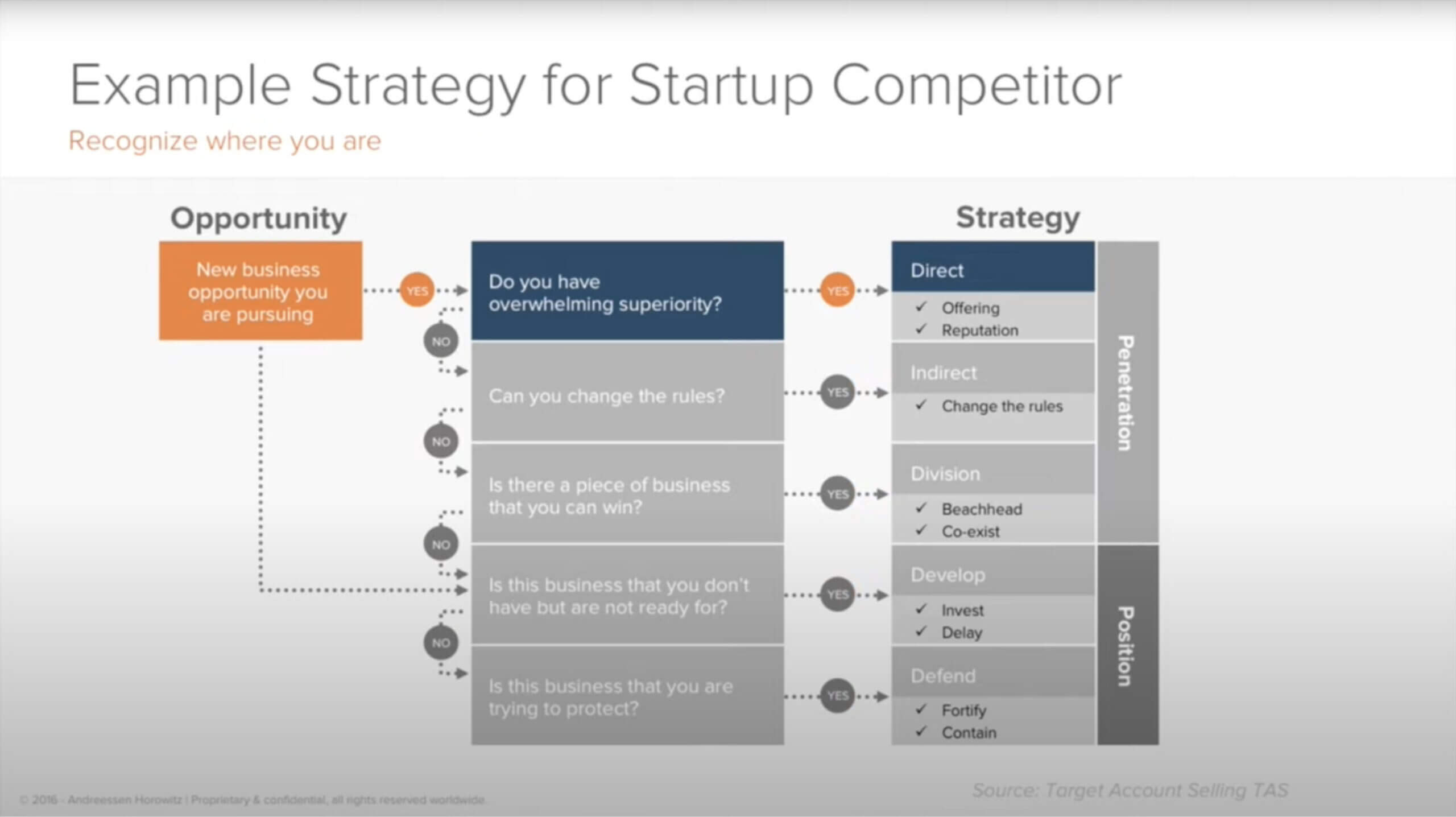

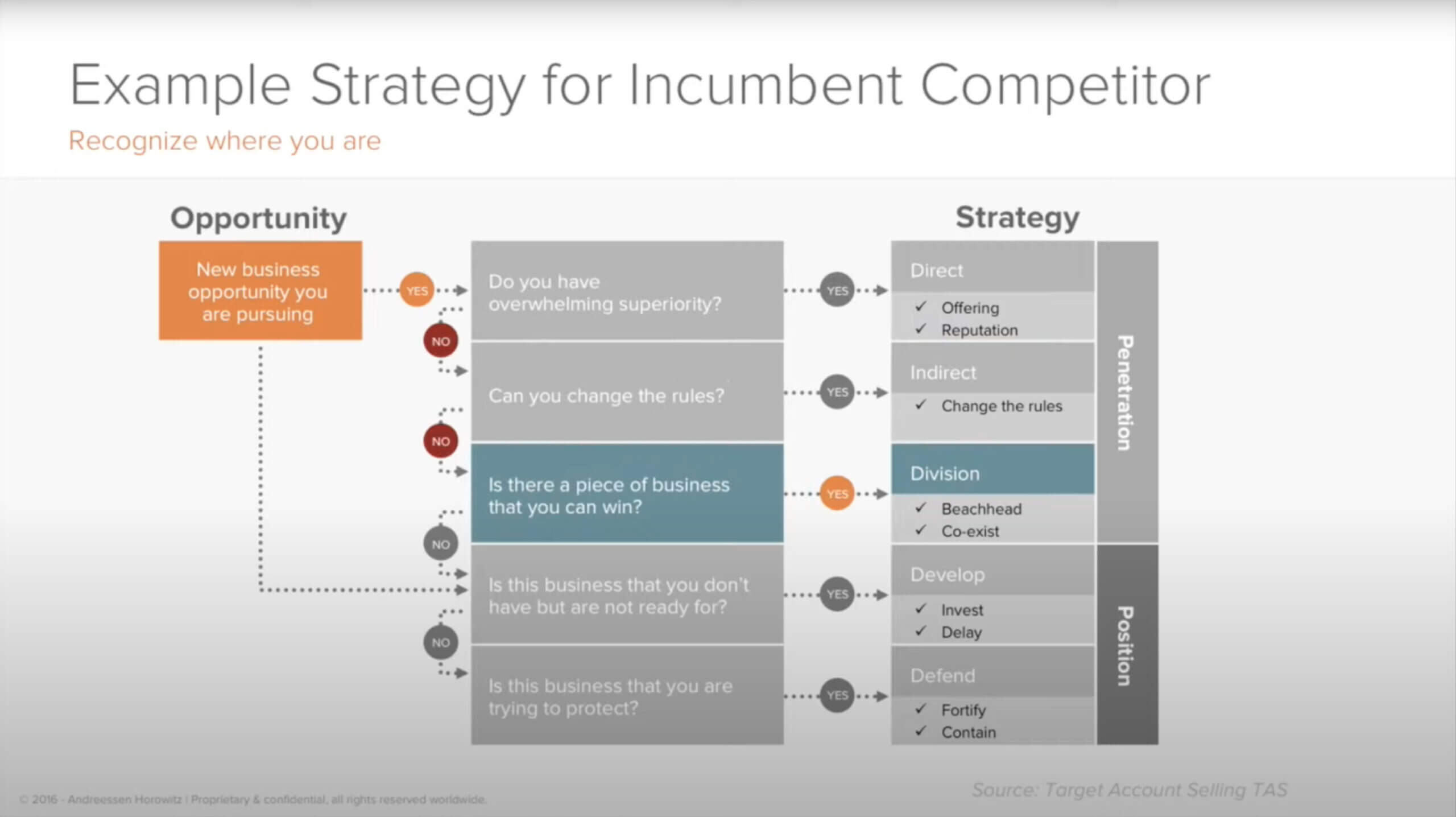

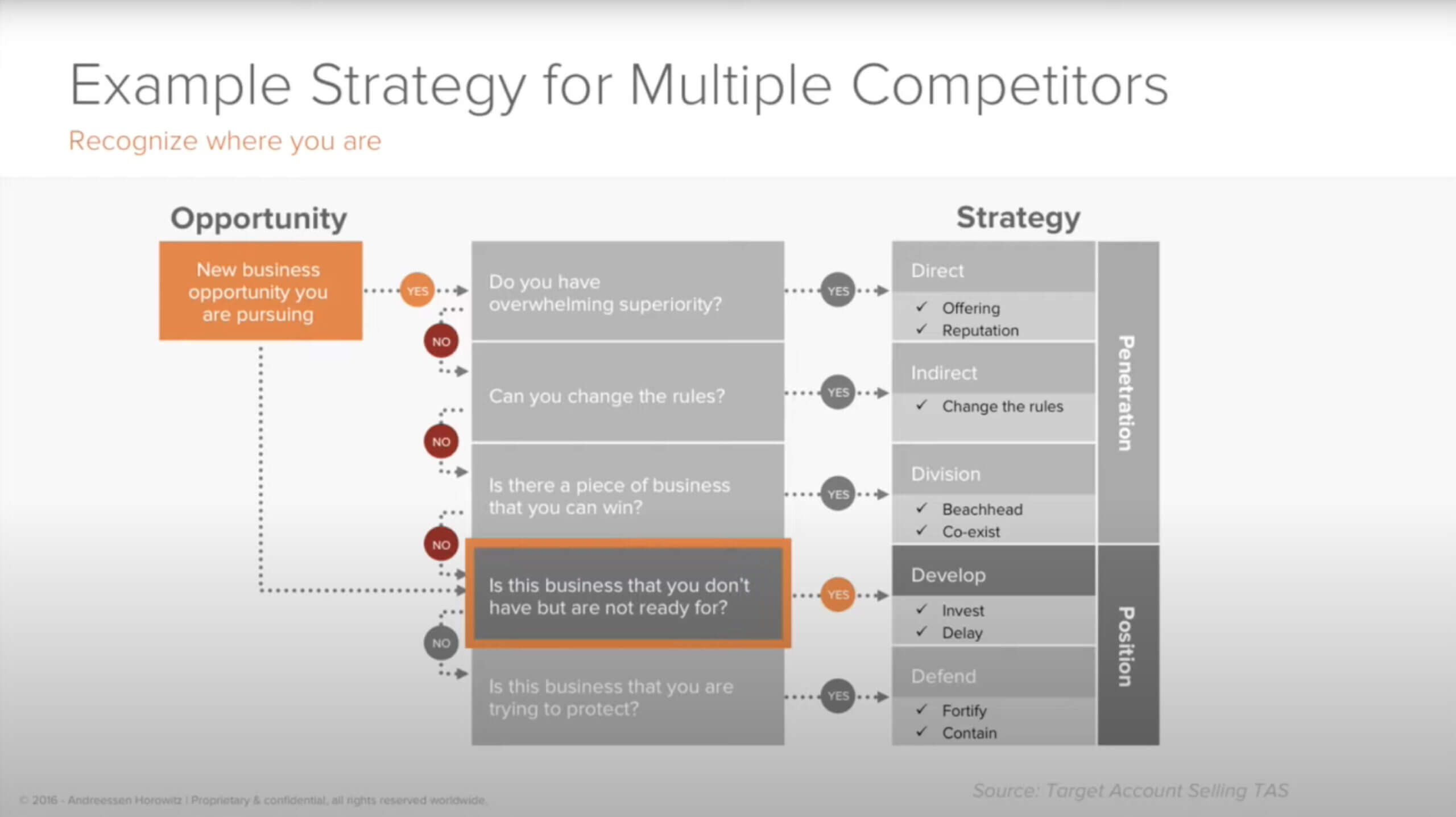

Another thing we need to think about as we’re going into a competitive situation is that I may need multiple strategies including direct, indirect, divide, develop, and defend. Pulling from the TAS methodology (target account selling), I may be in a situation—and this is very common—where I’m going to need different strategies for different competitors.

For example, if I have direct overwhelming superiority versus another startup of similar size, I’ll definitely take a direct strategy. This may be the only strategy someone has or they may try to take a direct approach when they really don’t understand that they’re not in a position to do a direct strategy. That can cause a lot of problems.

I may have another competitor where there’s a piece of the business I can win, which means I need to take a divide strategy. Maybe this is an incumbent and I have to coexist with them for a while because of the political situation. Or, I’m doing a bottom-up motion and I can get the departments that the users and user managers are recognizing but the senior executives have made a big political decision a long time ago and it’s just going to be hard to tear something out. That’s more a divide-type strategy for an incumbent.

Similarly, I might need to develop a strategy when I’m not quite ready to take the whole business. Again, I can get a piece of it, but I don’t want a decision to be made right now because we’re just not ready or I’m not in a position, so I want to slow things down. In fact, some of my best efforts in the campaigns I’ve been involved with have been around stopping deals from getting done versus actually getting them. Once these big investments are made, it can be a long time and, in a lot of cases, you’re never going to get back in there. It really is do or die, so slowing things down until you are ready—maybe that’s from a selling standpoint and you’re positioning the account, maybe it is from a product standpoint—but it’s super critical to think about things like that and get granular on what your strategies are versus your competitors and the situation.

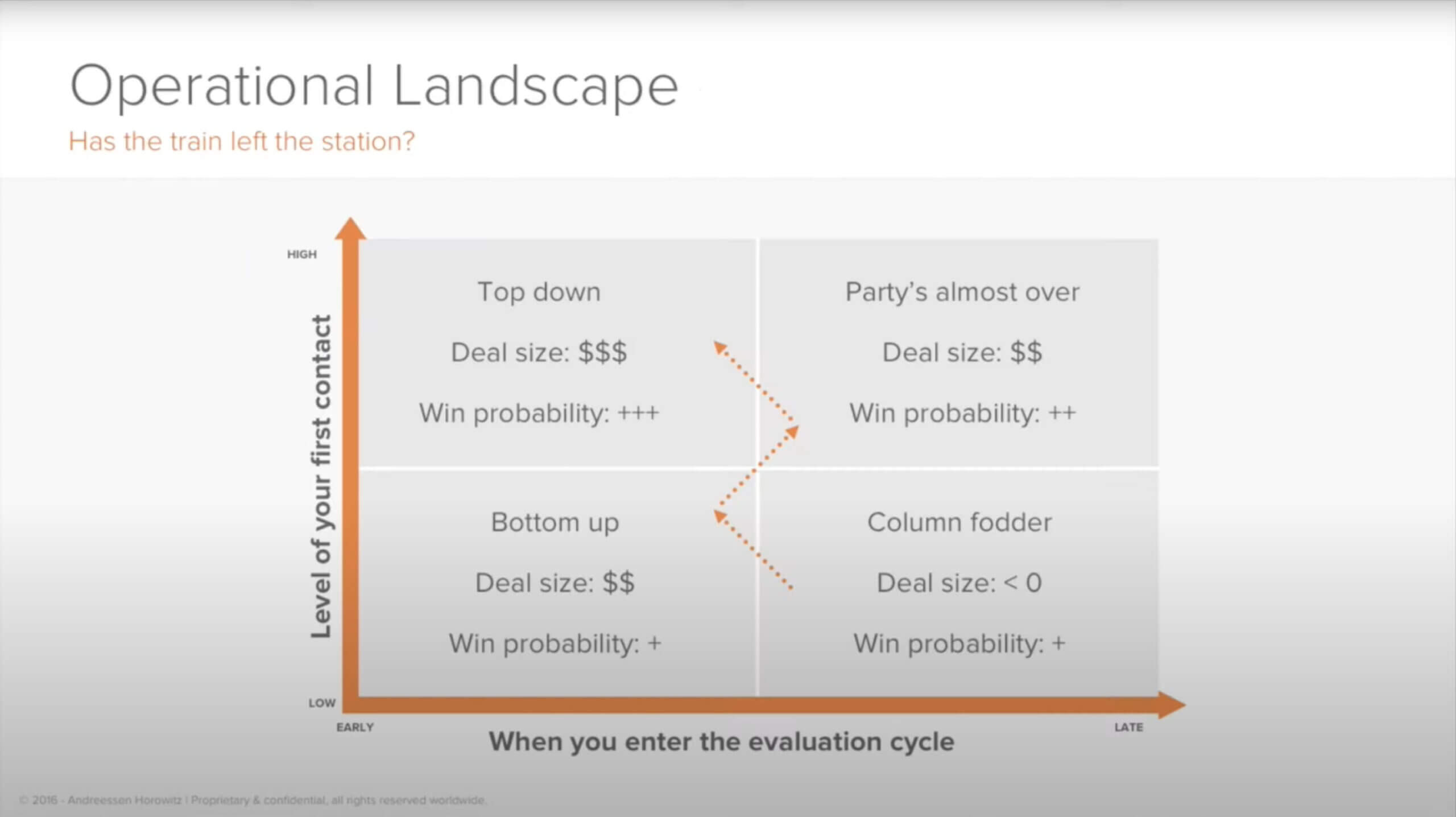

The other thing to think about is time and where I am at in the particular prospect or account that I’m calling on. If the party’s already begun with a particular prospect or account and I’m behind and competitors come in and define the criteria, I do not have the time and cannot afford to be working bottom-up in an organization. I have to escalate and get high to see if I can get in. If they’re not working on a hot initiative then I have the time and capability of starting low and working my way up. Having that situational awareness as we go into competitive situations is crucial because that’s going to drive a lot of things.

Defining the buying process

Now we’re getting ready to enter into the real meat of competing. We’ve answered that question: why do anything? The prospect or customers are looking at multiple options, including doing nothing. They’re pulling a lot of different people in to look at things, and we really need to be thinking about the following things: How do we position, manage, and execute the validation event process, and hopefully lock out our competition early?

The other thing to remember is—I see it over and over again—there’s this tendency, particularly in startups and in high growth situations, to wait for the buyer or the prospect to define the criteria and the buying process. What we have to remember is they might not have bought something like this before, or they might have bought something like this before but it was in the on-prem world and now we’re selling a SaaS solution. Or it was a proprietary closed software on an appliance but now it’s open-source and out of the cloud, and it was bought by developers and used by the operations team but now it’s DevOps.

Organizations are coming together and things are changing, and they might not recognize that they may be behind that adoption curve. But we can help them. The earlier we can really understand and help the customer and say, “Here’s how it’s being done,” the easier it is for us to help define that criteria upfront or help our prospects with their criteria. Part of this is how you go about technically validating—and this is a tough one.

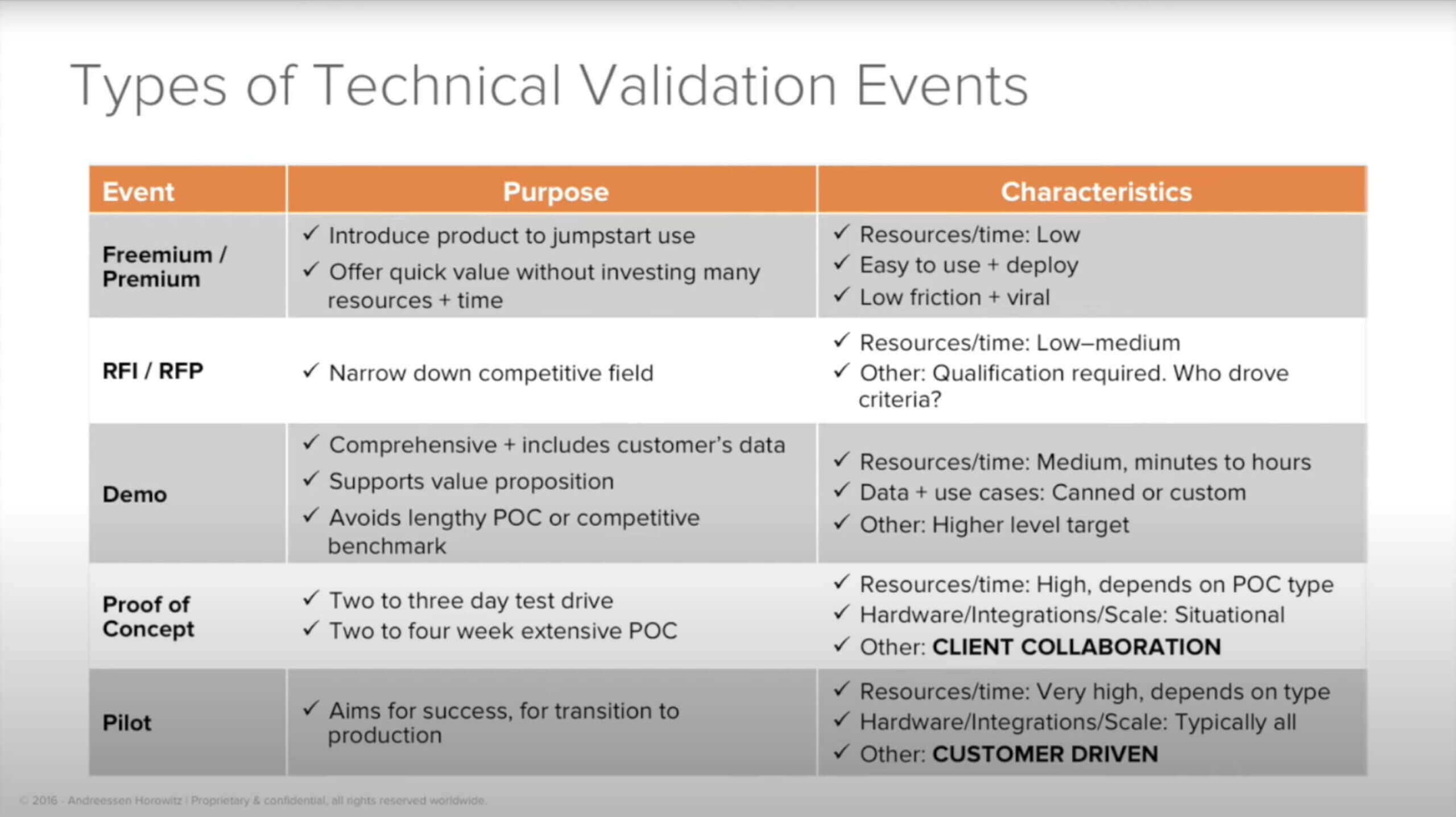

You may be using a freemium to premium or an open source type model, or it’s bottom-up. To really nail the whole process of moving from freemium or open source to a package situation with additional functionality, you need to get out in front and help define how you’re doing a demonstration, proof of concept, or a pilot. It’s important to map that all out and think about it through those three lenses: What are the business users going to care about? What’s the technical qualification? What do the actual evaluators get out of it?

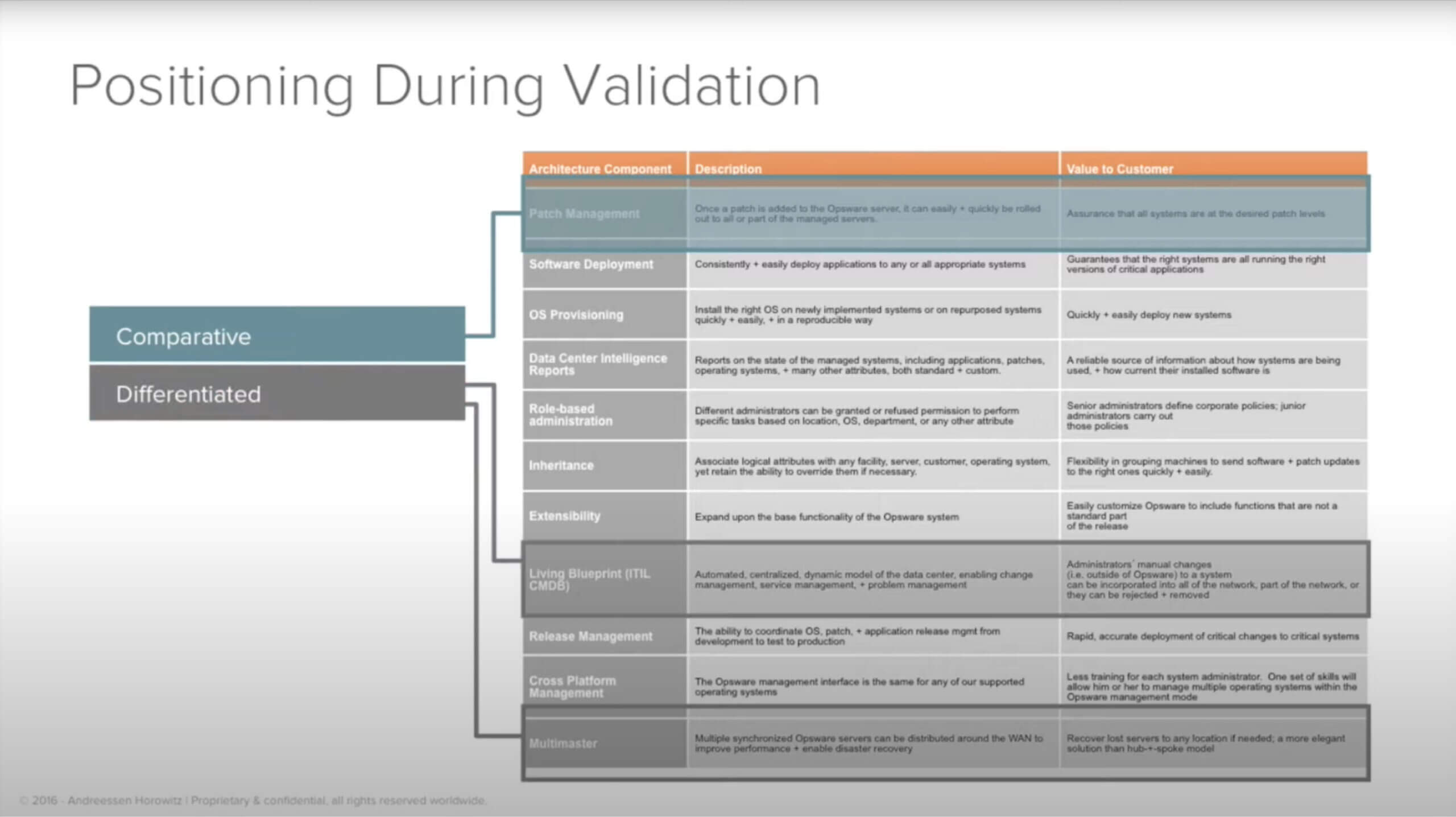

Then get very granular with your own understanding of not only yourself, but all your competition. What’s truly comparative? What makes me different from every single competitor? That’s going to be important as we step through the technical validation, whether that’s moving from freemium to enterprise or going on-site with a pre-sales or services team and showing how things would scale in high-end enterprise situations. This is our opportunity to really set traps for our competition versus step in them. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather be the one out in the forest setting the traps versus the one stepping in them. If you’re wandering around out there and you step in a trap, you’re going to die pretty quickly.

If I’m getting an RFI or an RFP and I haven’t influenced it, I’ve probably wasted my time. Or, if I understand the competition to the point where I can see that they’ve defined this part of an RFI or RFP type process, I can probably escalate in and see if we can get our criteria in and potentially even educate the customer that they might be going on the wrong path because they’re not looking at these things. Doing so is an easy way of qualifying whether I should be playing in this process or not versus kidding ourselves by entering into a situation where we have a high, high probability of losing.

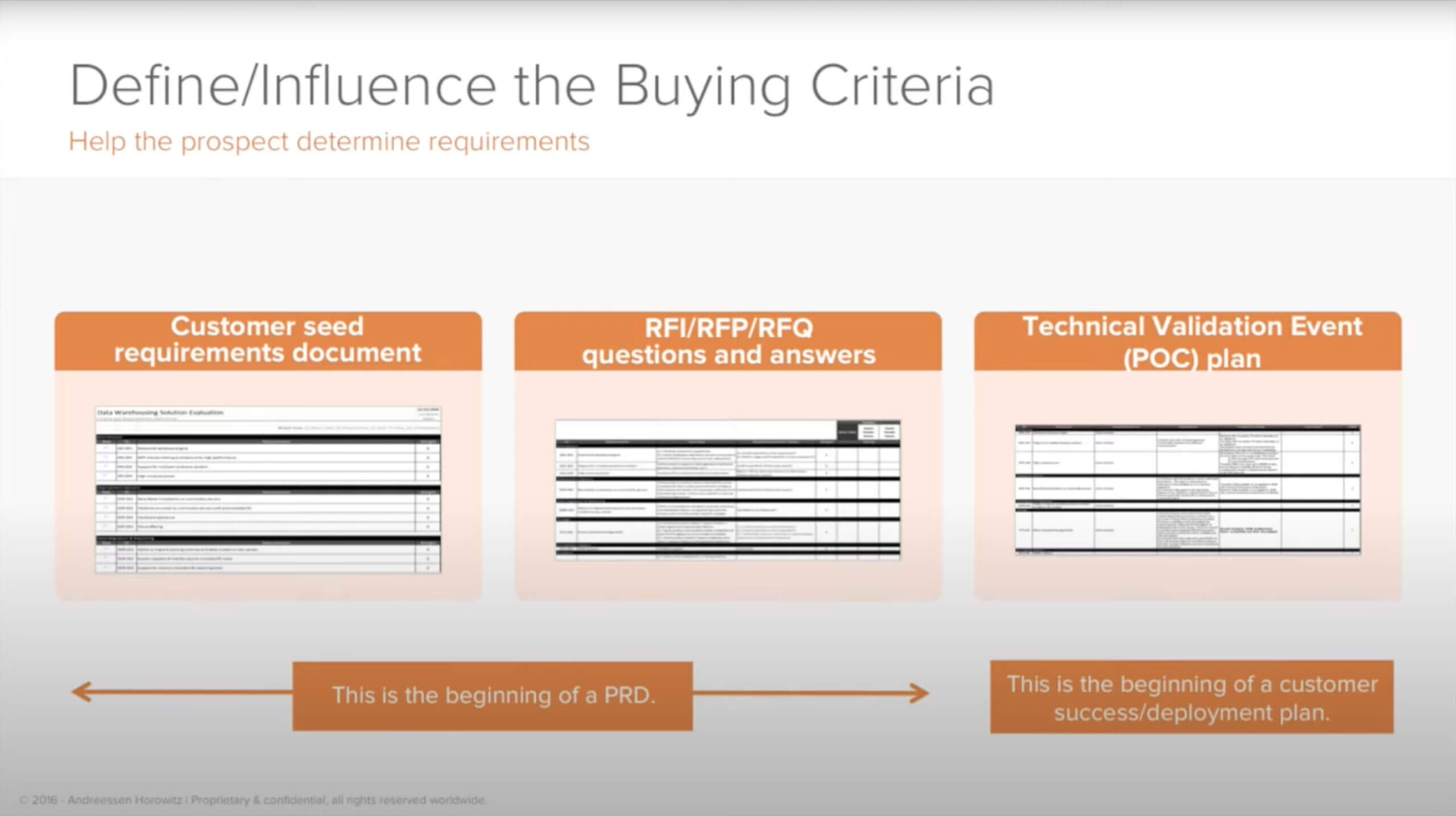

We want to understand the RFI or RFP in very, very, very granular detail and be able to help with the process and partner with marketing as well as product management and customer success teams to build out customer requirements documents that we can seed into accounts early on. The customer may have a lot of this information if they’re really deep in the area that you’re selling in, but they may not. What you’re doing is new, so there are a lot of things they aren’t aware of that you’ll hopefully be bringing to the table and making their job easier.

List all the questions they may ask, know your answers and your gaps, then use that information to build out a technical validation event document or a customer evaluation document and a PLC plan, which allows you to be prescriptive. Startups or high-growth companies can use this information as the foundation for a PRD (product requirements document) for engineering, product management, and marketing. We understand our gaps and we’ve got our eye on how we can close those gaps in our product to make it ready for the enterprise, particularly if we’re in a bottoms up situation where we land but need to expand.

The quicker we get customer feedback the better. This is the beginning of the process of setting up for our customer success deployment and training plan to make sure that we have successful deployments. It’s very important to do this early and understand that it’s going to be integrated across the entire go-to-market as well as deployment—and understand how it relates back to our product development engine.

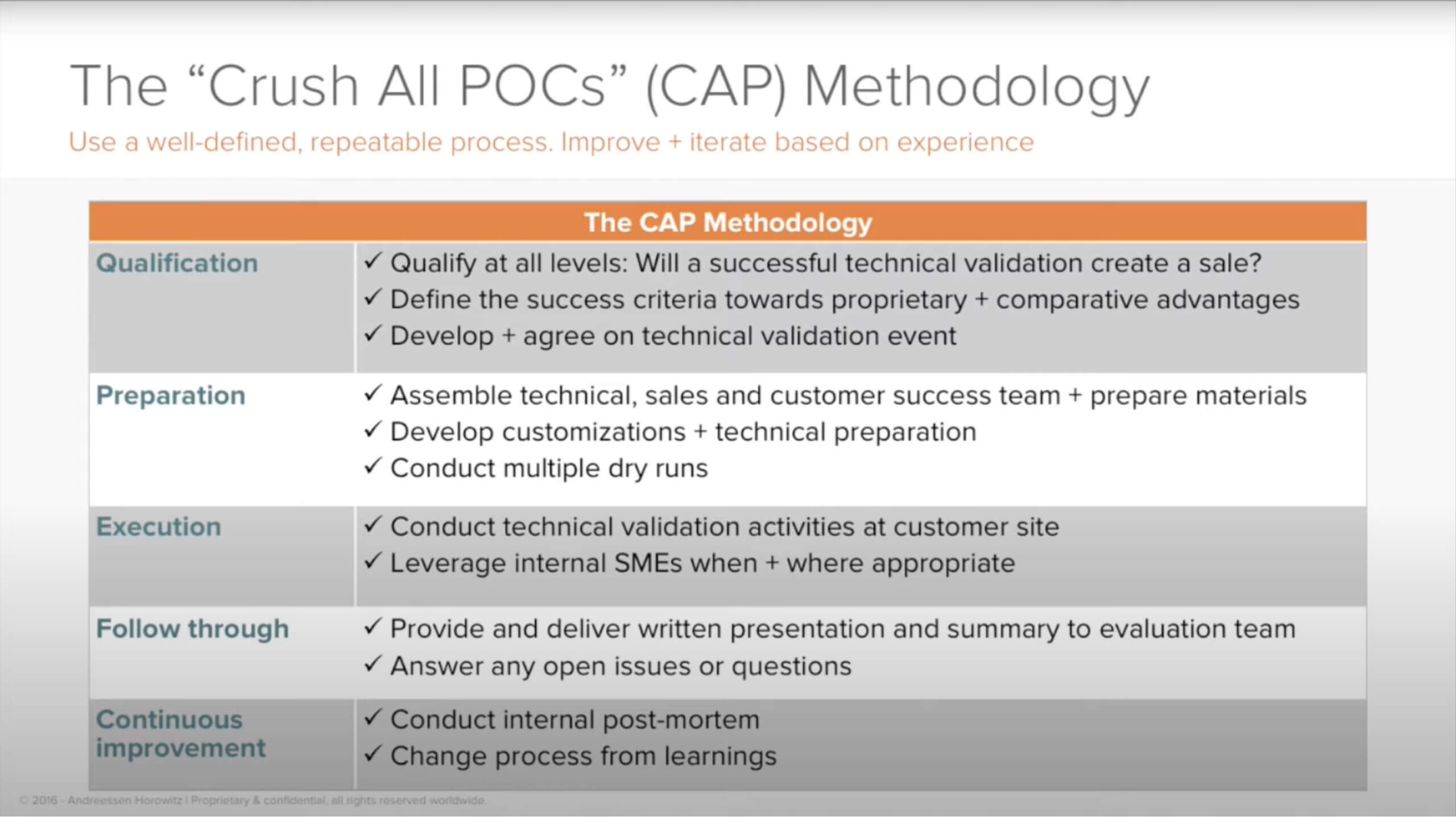

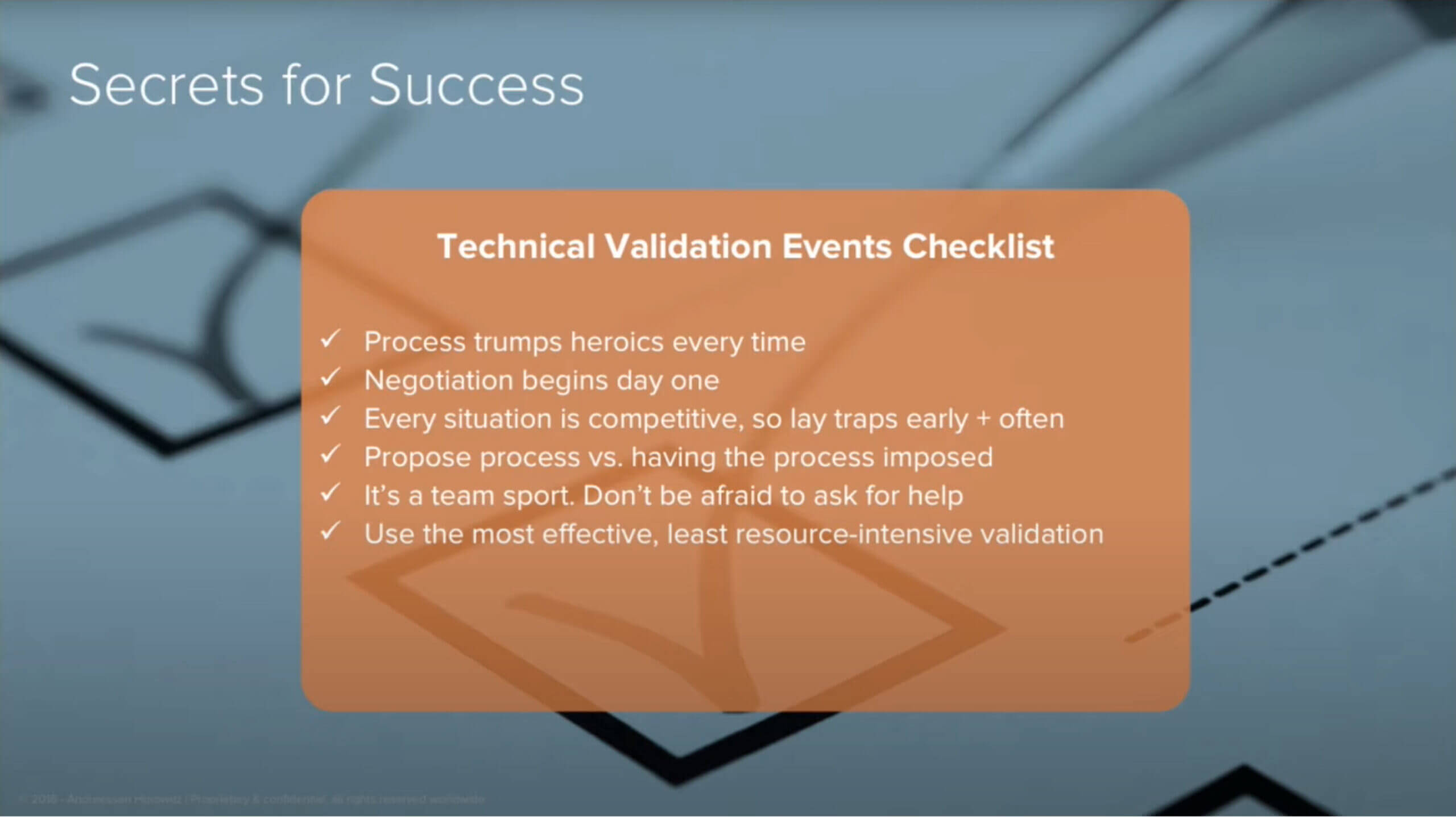

Then we want to get into execution. Let’s get extremely detail-oriented about how we crush our proof of concept and technical validation events using well-defined, repeatable processes. We need to be clear on the type of involvement that we’re going to need and the size of the deal, and understand that process trumps heroics every time. We’re always negotiating and qualifying, should we do this? All this extra work, is this qualified? If we do this, are we going to be successful? Are we setting competitive traps and being prescriptive of the process versus having it imposed upon us?

The process and requirements need to be mutually agreed upon. Both sides, the buying and the selling side, are expending resources. Sometimes you need to move up and have that conversation with the executives. “We’re going on this path with your technical team. If we go down this path, what is your decision and buying criteria? Is there going to be some gold at the end of the rainbow or are we just dealing with a bunch of window shoppers?” It’s just as positive for me to have that conversation with the C-level executive and find out that no, they’re not buying anything. I’d rather know that early versus after I’ve put a whole sales team and technical resources on it because, as a startup or a high-growth company, we only have so much. Even the large companies shouldn’t be doing that.

Technical validation

Next we move to the technical validation event process. It’s custom and will vary—it could be completely self-serve for land and expand or it could require a lot more effort if we’re going to do the bigger deals.

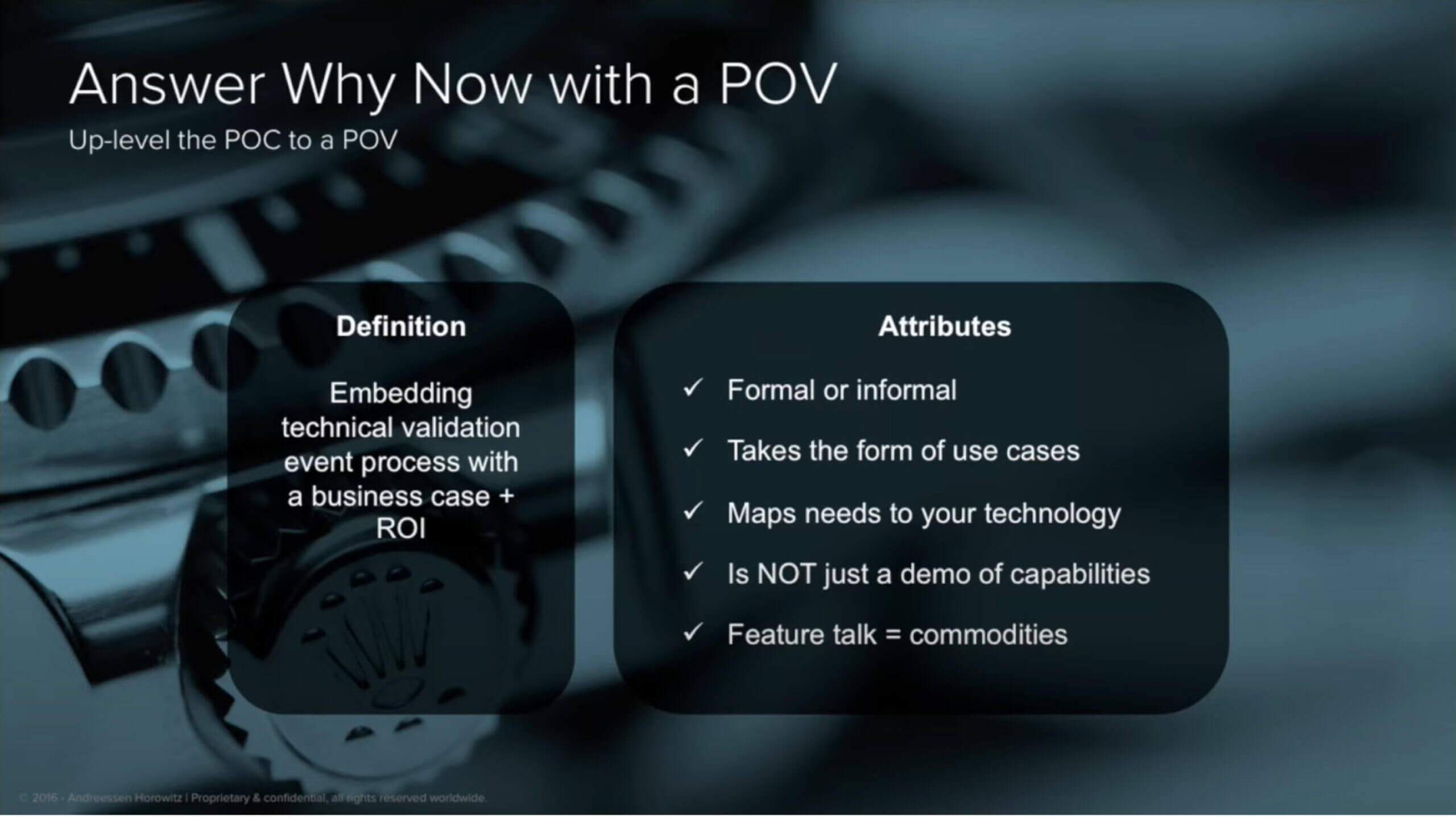

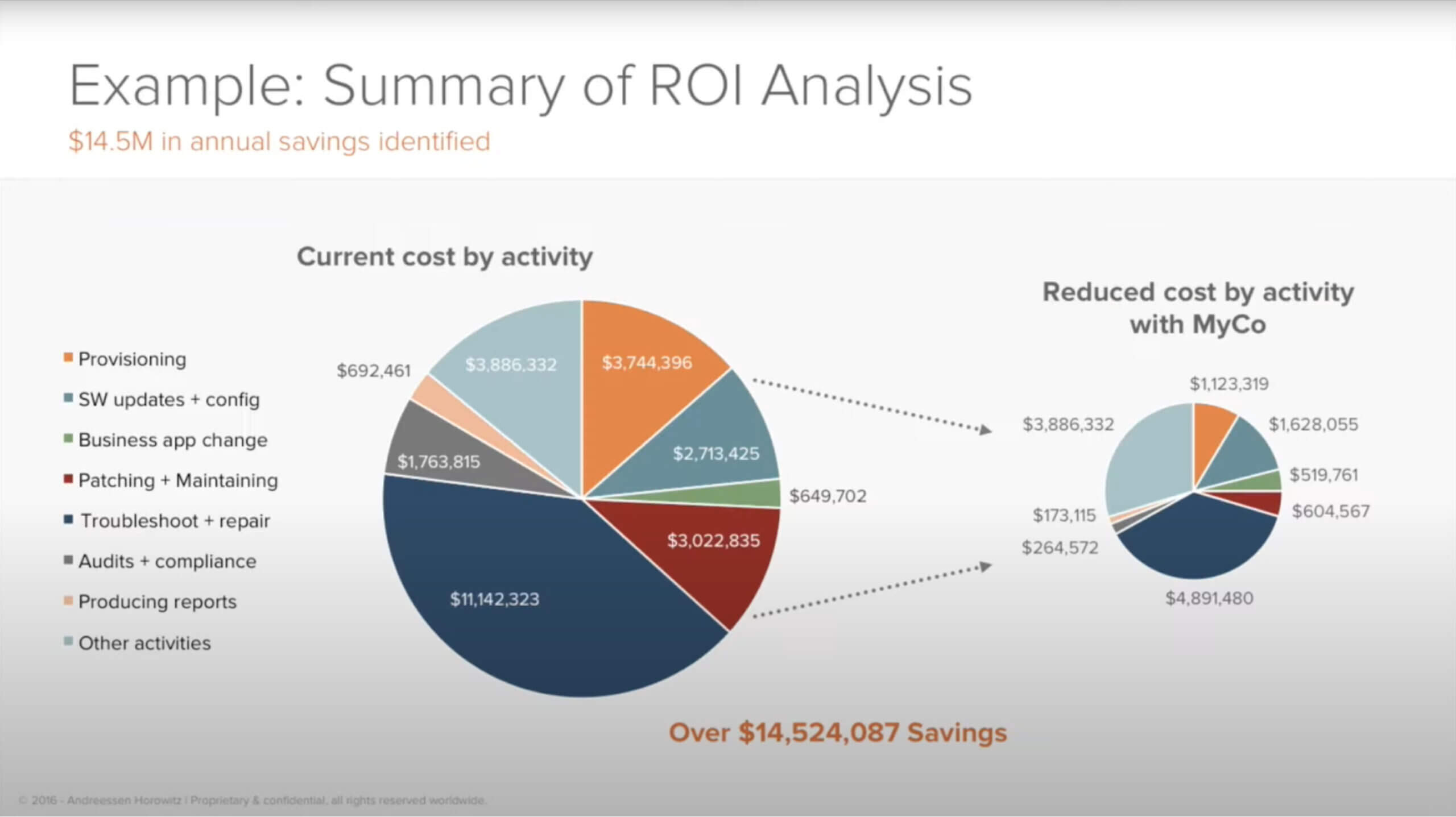

It’s important to know that we’re doing that technical validation event process to answer that middle question: Why should I choose you over the competition? The third question that’s coming up is “why now?” We’re at the point of the spear and getting through that competitive situation, but there’s no better time to gather financial metrics and quantify what this means to the prospect from a business standpoint. The earlier we pull in and embed in our technical validation event process, the better because we can make the business case and quantify ROI.

What I see happen over and over is we go through the process and technically win, and then we get to the end and we’ve got something on the forecast and the customer has to put an ROI together. They might even run it up to executives or finance. We’ve wasted all that time where we’re in the bowels of the company and we could have shown that, if we do X, Y, Z, we’re going to save you this in productivity and total cost of ownership. You don’t have to buy as much hardware because we’re going to go to SaaS or we move from CapEx to operating. We had that opportunity and we weren’t prescriptive about it.

Quantifying ROI

We’re going to know if we’ve really put a high-end go-to-market enterprise sales force and process together because we can demonstrate and prove cost savings impact upfront. Putting that in the front of the process or in the middle of the process with your technical validation event is very important. Later, when we’re answering the “why now?” question, the executives are going to want to know why now versus the other things they can do.

How do I reduce cost, mitigate risk, or even potentially augment revenue? I can break that down into two buckets. One, what are the hard dollar savings of reducing cost and mitigating risk? Two, what are the softer dollars that I might not get as much credit for? It’s important to show and prove out how we are going to do it and map that over the technical validation event process.

One of the things this does is insulate us from a sales process standpoint, particularly later on, where we might need to negotiate because I’m rolling up a 6, 7, or even 8-digit proposal that’s getting flipped over the wall from the evaluating team to the executives and they’re hammering me about a per unit price or size of the deal. Let’s say it’s a $10M proposal but I’ve actually done the work with them and everybody’s agreed that we can save them $100 or $500M. It’s a little tougher to beat me over the head on price or technical differentiation if I’ve got use cases that are going to have a higher financial impact than a competitor.

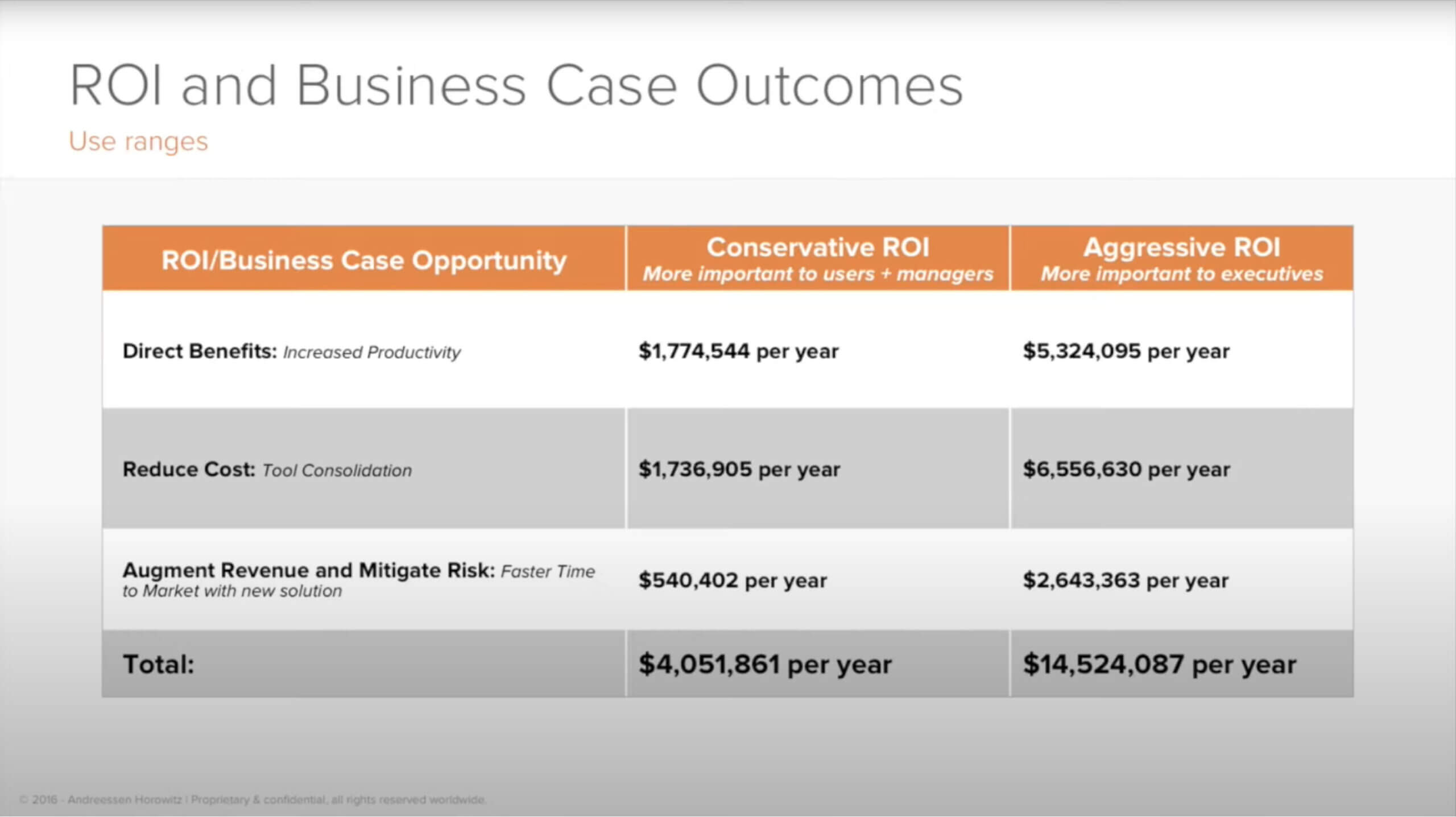

Again, get that spreadsheet out and get granular and detailed so you can understand what you can do for your customers with an investment in your solution. What does that mean financially? Put that together. What are the questions? As a rule of thumb, put together ranges, conservative versus aggressive, because it’s very rare that you’re going to go in and get the entire environment upfront. That’s going to build over time.

If you do the big ROI upfront and it is attached to a high-level funded aggressive initiative with the executives, your chances of getting more investment and more deployment done upfront are going to be a lot higher. Different people in the organization are going to want to see or even be held accountable to different things. The bigger number is going to be more appealing to an executive than the users who are charged with evaluating your solution. They might not want to roll up the aggressive figure. They might only want to do the figure that’s going to give them the internal IRR, the internal rate of return, to get the thing funded—but they don’t want it held over their heads. The executive might want to see what is possible. Make sure you put these in ranges, get agreement as you go along, and you’re validating. Then put that together and show the possibilities of that ROI diagnostic and business case analysis.

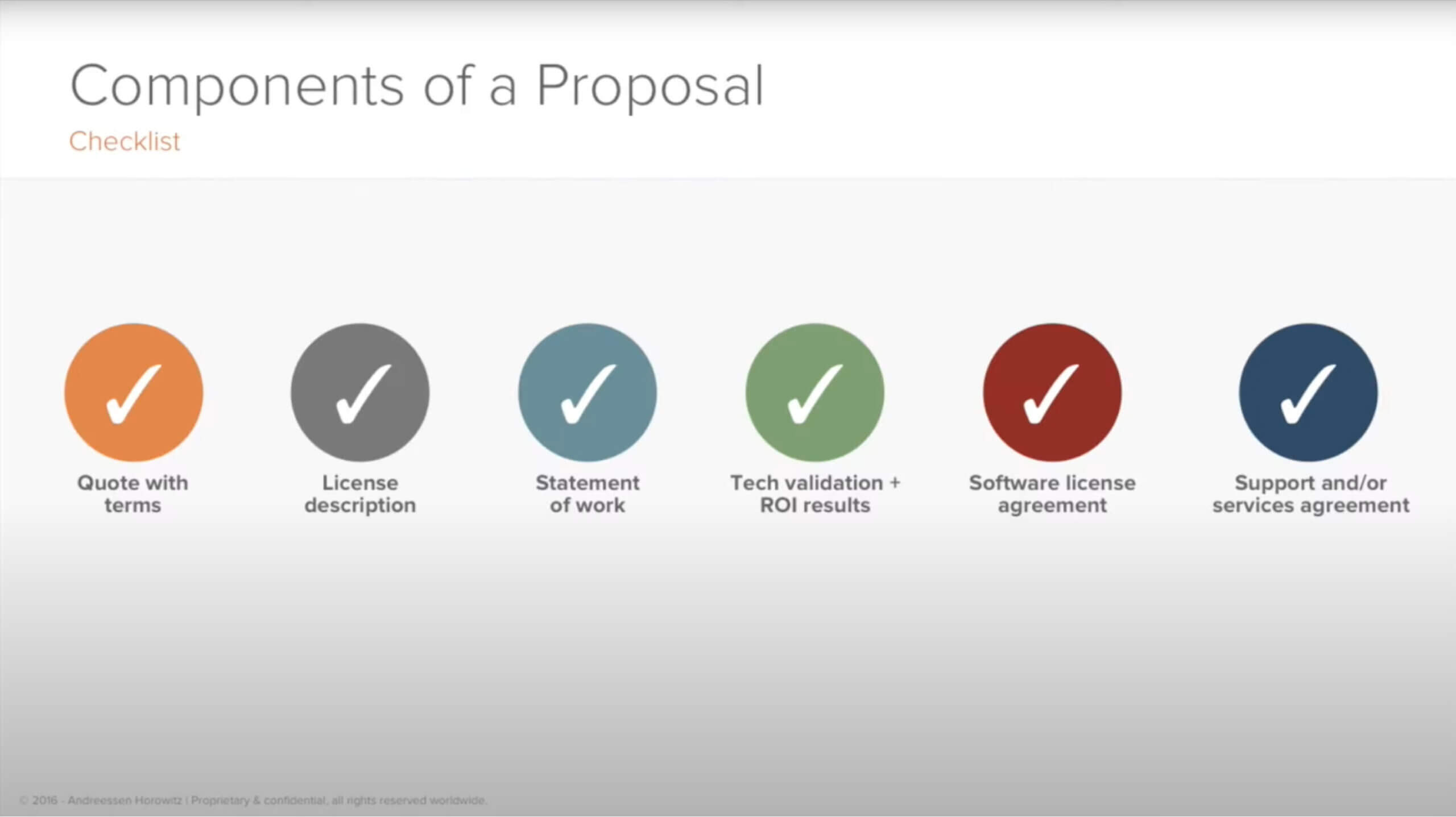

Once I’m armed with that I’m really feeling comfortable, particularly on the larger deals where the next phase is the proposal. We’ve stepped through two questions: “Why do anything?” and “Why you over the competition?” Now we’re in the “why now” and we’re rolling up a proposal. We feel confident that we’ve influenced buying criteria, we’ve put an ROI together, and we’re confirming a decision process. We’ve built out a proposal template and quote tools and we’ve got the ROI model and the deployment plan coming together. I actually have a plan going forward above and beyond that initial investment and attached to it is the technical validation event process to show what the deployment plan would look like. We’re looking at the different components of the proposal and it is going to be super custom—and you’re feeling confident about it.

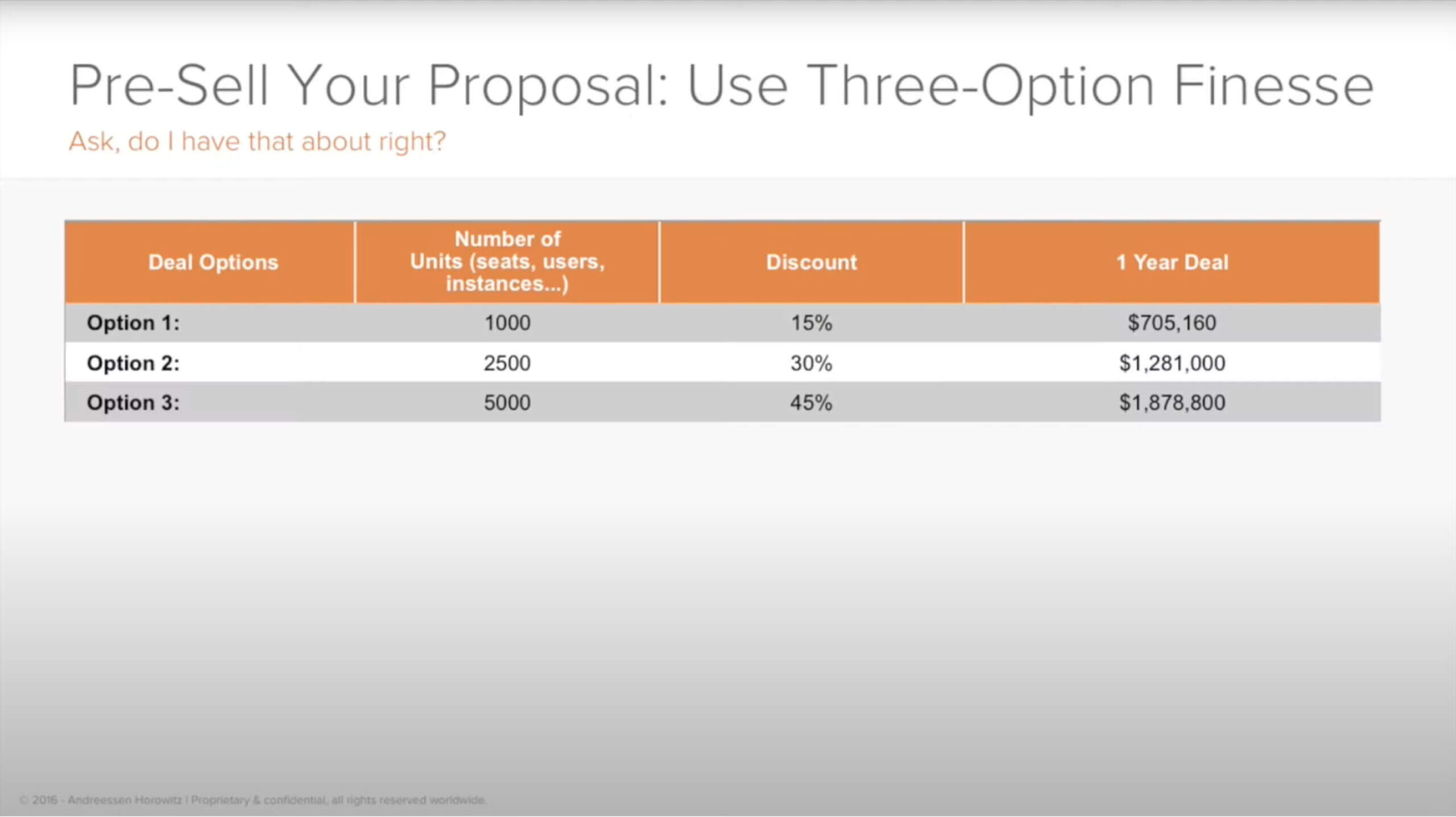

Again, we want to give options. It’s very rare that we get an opportunity to get the entire environment. I see it over and over again in startup and high-growth situations: We spend so much time on the first quote and it’s going to be for a hundred or a thousand units, but what would it be if we did the whole thing and we took care of that customer across their entire environment?

Look at the long-term possibilities

In a lot of cases, not enough time is spent understanding what that’s going to mean long term, that the initial deal is going to turn into a much bigger one. As we move up in an organization that we’re selling to, one of the big questions that the decision-makers, an economic buyer or a high-end technical buyer, are always going to be asking is: What does this mean? It’s great that we’re going to do this on a business unit or department level, or even as a phased approach—but what’s it going to cost us over time and what’s that ROI going to be over time?

In a lot of startup situations we’re so focused on the initial deal, we forget that we’re going to create friction if we don’t give them options in the proposal and show what it’s going to look like over time. It really costs a lot of people a lot of time, particularly when things get thrown over the wall for procurement. The first thing the prospect can ask is, “If I don’t know what 5,000 units is going to cost me, what good is a quote for 1,000?” Even though I’m telling you I want a quote for 1,000, I need to understand the long-term potential for that account. You can take a lot of friction off the table by already having these pre-built and even proposed along the line.

Giving options also puts me in a position to potentially incentivize them to a larger deal upfront, particularly if I’ve done a very good job with the technical validation event and the ROI diagnostic. By proving the value and putting this into a systematic format for your sales teams, they can incentivize the customer to move forward a lot quicker.

Adapting when your context changes

We want to stop and ask constantly as we’re going through this process: What’s our political position? Has the decision criteria changed? Is the process changing? What are all the competitors doing? Where am I at from a validation standpoint and funding process? Then constantly churn that account plan. A lot of this needs to be baked into your CRM solution and into your cadence of forecasting and inspection.

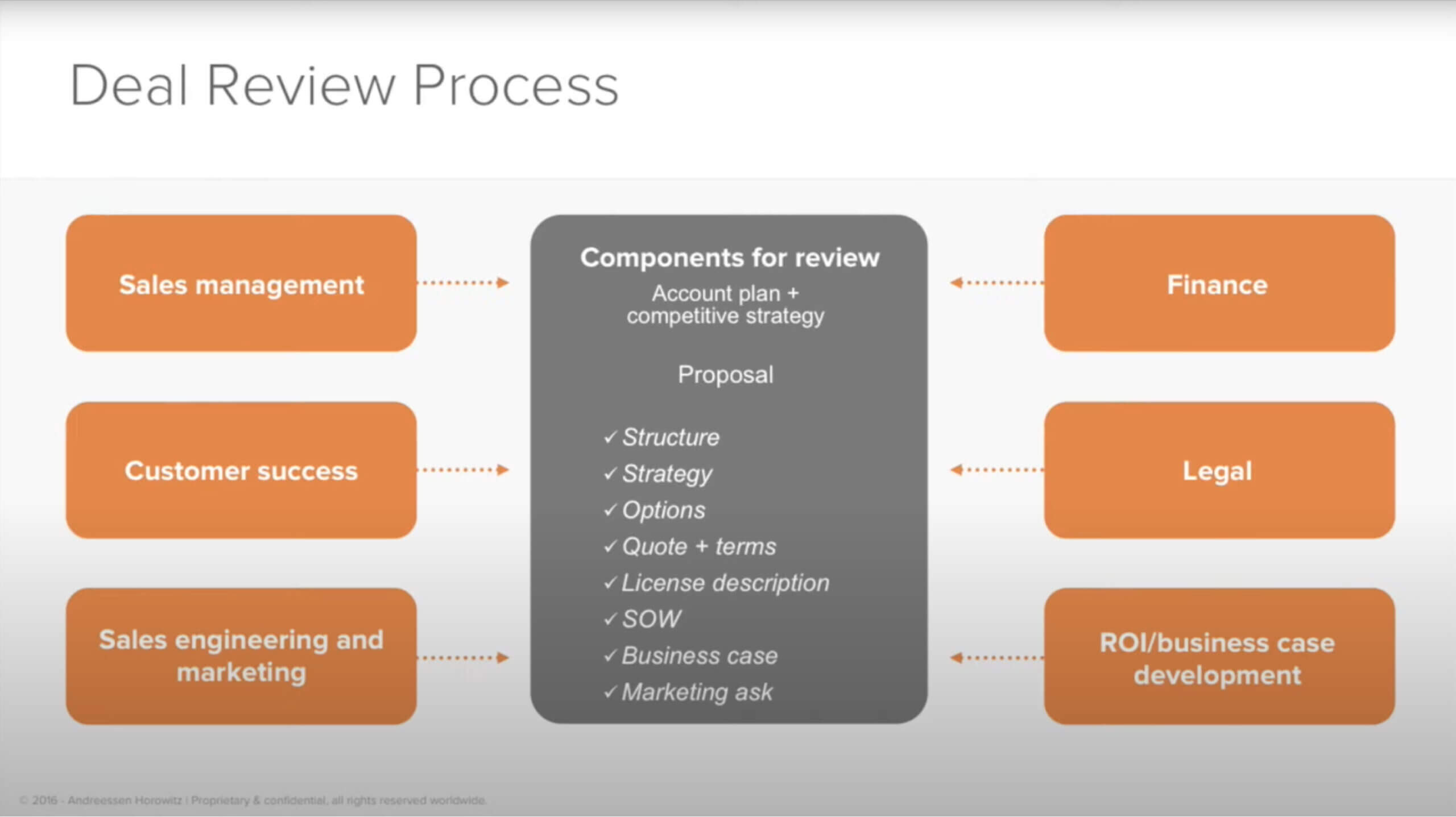

Then customize and formalize your deal process and approval process. You might have different processes for the high-volume, low-dollar transactions versus the larger deals, but really bake in and automate everything as much as possible.

Negotiate and close

Then we’re moving on to negotiate and close, and final contracts. As you bring it all together, look at your sales process from the top. What’s the buyer process overlaying my sales process? What are all the other teams underneath going to be doing over and above just sales, such as my sales engineers and customer success people? What are the customer-verifiable outcomes, questions, and deliverables I need to step through? What are the sales tools I need to be using and automating to enable this? What are the forecasting guidelines? We cover those in-depth in other modules.

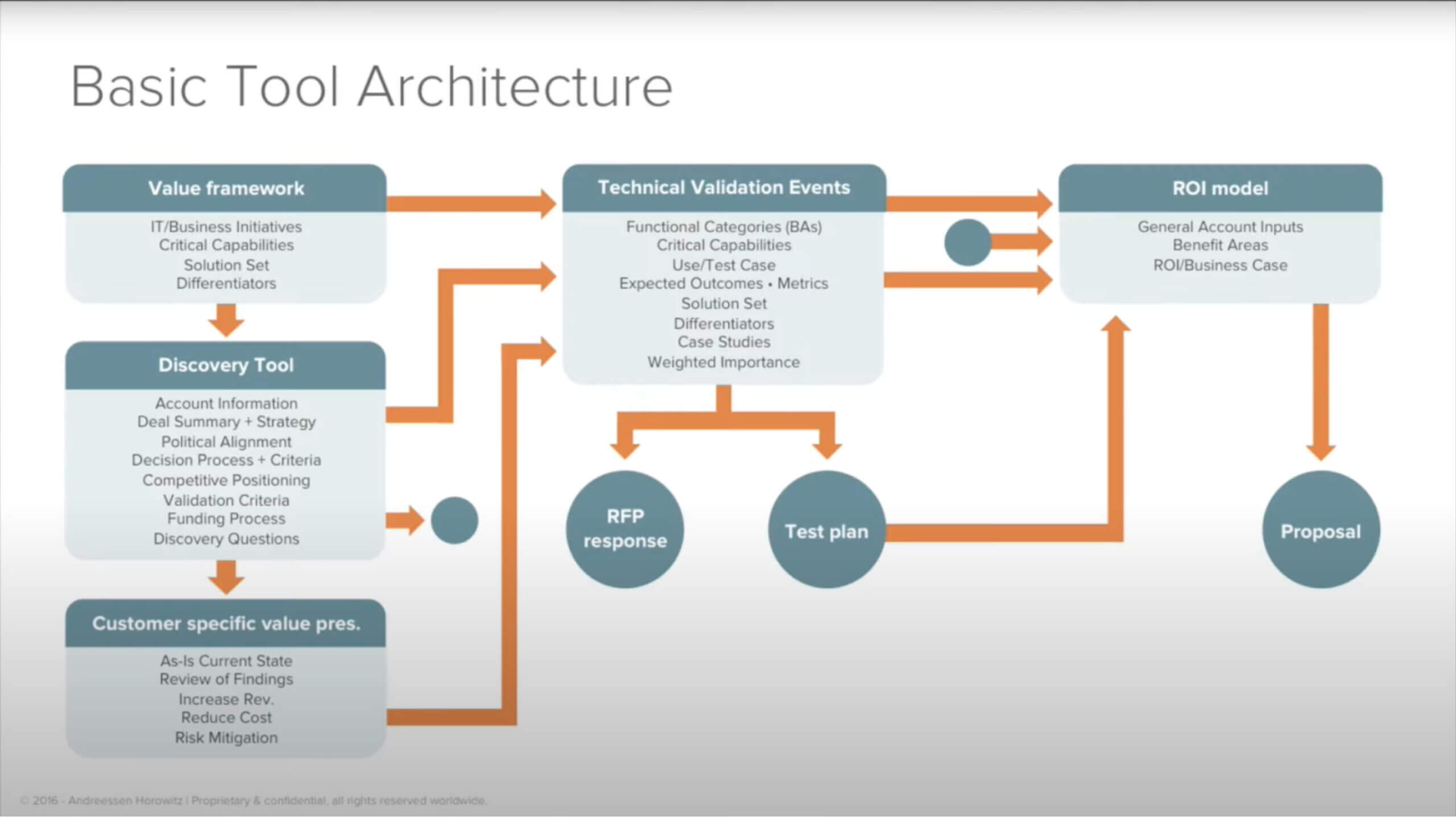

Then start designing the tool architecture to support the process. You’re never going to be done with these buckets and things will always be changing. We’re always going to be upgrading, but having that context for what I need to be asking is important.

As we move from negotiating to close in field sales, it’s also important to understand this is directly related to forecasting. That forecasting lays over the top of your sales process, forecast process, cadence, and execution. We have a whole separate module in our sales and marketing boot camp that covers that. These are very interrelated, but we want to make sure everyone understands that a sales process and forecast process requires a whole different layer of inspection and process that you need to think about, particularly as you scale. We will cover that later.

We’ll wrap up with deploying and developing. I have it in the regular sales process because, again, it’s interrelated. How am I going to partner with my customer? What have I done to put the beginnings of a customer deployment plan or a customer success plan together? Because the best and easiest place to sell something is where I’ve already sold something. I’ve gone through this whole process with someone, and while it’s rare that I’m going to get 100% of the opportunity upfront, it’s the beginning of a journey with the customer. We’re deploying to develop, we’re working with the customer success team, we’re implementing, we’re building, we’re supporting, we’re starting nurturing, and we’re creating new opportunities to cross-sell, to upsell, and renew. It’s all intertwined and it’s a lot easier to go through the second time if we do a good job on the customer success front.

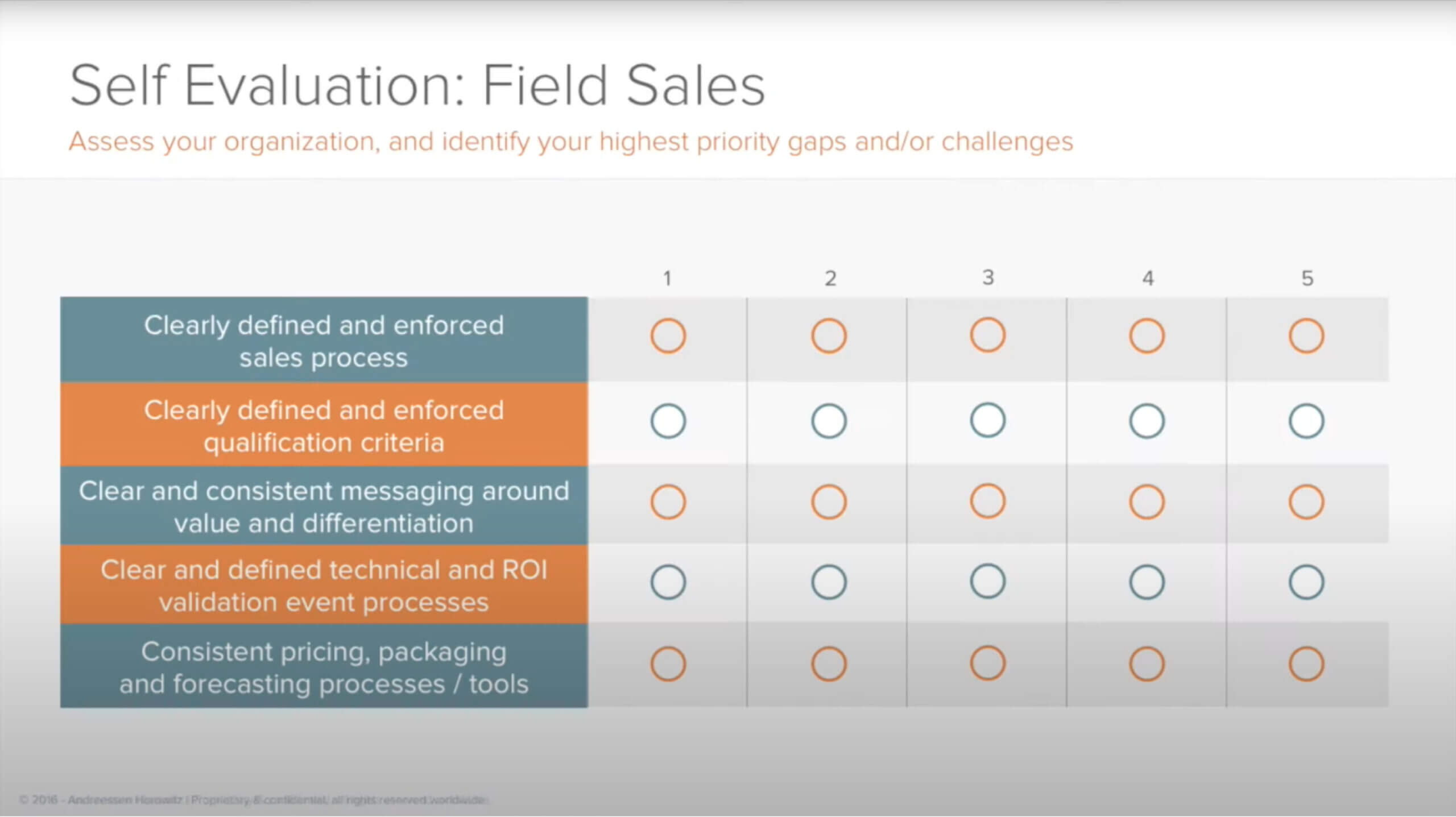

Self-evaluation

Here are some high-level questions: Where are you at from a sales force definition? Is your sales process clearly defined and enforced? How well are you qualifying customer deliverables before you can move on to the next stages and gates? Do you have clear and consistent messaging around your value and differentiation? Do you have a clearly defined technical validation event process? Are you really investing enough on helping your prospects put a business case or ROI diagnostic together, or are you relying on them to do that?

Lastly, how much have you thought through pricing consistency, packaging, and size of deals? We’re going to tee that all up for you in another module about forecasting processes and tools.

On that note, this wraps up the field sales go-to-market boot camp section.