Most recent macro trends – cloud compute, social, mobile, crypto, AI – that have reshaped the technology landscape are rooted in new technical capabilities or pushing the frontier of product form factors. Another shock to the system is emerging today, driven not by the underlying technology, but by an evolution in customer buying behavior. For shorthand, we think of this trend as “growth+sales”: the bottom-up growth motion eventually layered with top-down sales.

While this go-to-market strategy dates back to the early days of software, it is becoming the predominant method of going to market in many verticals, even in categories in which conventional wisdom might say it would never work. Think GitHub, Zoom, Qualtrics, Slack, Atlassian, PagerDuty, Yubico, Stripe, Plaid – all of these started with a product-led, bottom-up motion, followed later with top-down sales.

Growth+sales changes nearly everything about building an enterprise startup. It changes the way startups build products and the teams behind them, and how they structure sales and marketing. It changes how we as investors evaluate companies, particularly in the early rounds. And it changes how new companies compete with incumbent vendors, most of which are on their heels trying to figure out how to respond.

The most exciting consequence of this shift is that in nearly every category of enterprise technology, it puts the advantage squarely with the startups. When the initial route to market is focused on how much a product sells itself, the winners are the product visionaries, not veteran sales leaders pushing outdated software. Further, startups can unlock product-market fit without building a large sales organization up front, and consequently, unlock an organic base of users and bigger addressable markets than traditional enterprise sellers could ever reach.

Yet, while much has been written about how growth+sales has become a standard playbook, it’s no trivial feat to get the tactics right. We’d like to explore the hidden traps to avoid if growth+sales is right for your company.

When the initial route to market is focused on how much a product sells itself, the winners are the product visionaries, not veteran sales leaders pushing outdated software.The old world of enterprise go-to-market

Growth+sales is nothing new. In the early days of the software industry, users would mail in checks (or even cash!) to purchase shareware. In the 1990s, Netscape walked into unsuspecting enterprise sales opportunities armed with a long list of active users completely unknown to their respective IT departments. And in the early 2000s, Salesforce allowed customers to self-serve directly from the website to gain a foothold in the market against incumbent CRMs.

However, in each of these cases, the enterprise buyer still had to be trained to consume highly technical products for a deployment to reach meaningful scale. The resulting sales dynamics and product adoption behaviors have been the equilibrium ever since.

- Long, high-stakes, relationship-driven sales cycles: Since top-down products must ultimately win a long-term commitment from the enterprise buyer, a direct relationship is required to navigate the customer organization and educate multiple stakeholders on the product. In the typical pre-sales playbook, the account executive qualifies the account, finds the budget, and negotiates the price, while a sales engineer facilitates technical education around the product. Navigating this step alone can take months, quarters, or even longer depending on the complexity of the sale.

- Maximally complex products with painful user experience: Since effective top-down sales require a highly choreographed (and costly!) dance between pre-sales and the customer, product teams are incented to add more nobs to the product so these teams can sell more value and extract more dollars. Vendors get crossed off the list in vendor discovery if their product doesn’t check all the right boxes for the enterprise buyer, even if many of the boxes don’t actually deliver any value. This often creates a vicious cycle where more complex products give rise to longer sales cycles for more dollars, which then incentivizes even more complex products. For any user of legacy enterprise software, it doesn’t take long to realize that designing a seamless user experience is by no means a top priority for the vendor.

- Elaborate vendor discovery and procurement processes: In the traditional sales model beyond the early years of product-market fit, vendor discovery is largely driven by a combination of industry analysts placing category winners in the top right corner of the magic quadrant, field marketing asserting brand dominance on the conference circuit, and relentless sales reps promising that their software is the solution to all of a customer’s problems. From there, line of business executives and centralized IT buyers explore product validation through RFP processes, which often require pilots to compare efficacy across an entire field of competing vendors all making the same claims. Finally, the winning product is run through centralized procurement, during which the IT department puts a vendor through the security ringer and carefully monitors implementation and change management, while procurement managers negotiate the terms of the deal before ultimately signing on the dotted line.

New buyer, new motion

In growth+sales, all the complexity of the traditional sales cycle collapses into a single decision maker: the end user. The user isn’t going to read the analyst research report. The user won’t hear the sales pitch. And the user doesn’t care what lofty promises a vendor makes about all the bells and whistles of the product. The user only cares how well the product delivers on solving their problem.

Trying out new consumer apps is a daily ritual for most of us. Now, that same discovery behavior is coming to the workplace. Customers historically only accessible via top-down sales now empower users on the front line to expense the tools of their choice without ever dealing with the formal procurement motion. Growth+sales not only unlocks new decision makers, but also catalyzes new buying behavior from existing buyers who used to only consume via direct sales. The result is a drastically different status quo in which everyone is better off, especially the end user!

- The best products win: Modern design, seamless UX, speed, and features that get the job done are the competitive dimensions that matter to the end user. Today’s best products are often far simpler, having never been put through the endless RFP process checking feature boxes for a technical buyer. And when users can vote with their feet, the best product wins. For an obvious example, compare your least favorite old-school CRM to the new generation of work productivity tools.

- Product discovery driven by word of mouth: When users really love your product, they tell their peers, friends, anyone who will listen. This beachhead enables a much faster direct enterprise sales process than going in cold with no existing end user presence. When enterprise buyers are overwhelmed with vendor fatigue, they’re not interested in exploring relationships with new vendors without organic momentum inside their orgs to champion products. The interaction between the growth motion and the sales motion reinforce each other, significantly accelerating adoption at scale when sequenced effectively.

- Consumer-style growth tactics: When a startup really nails the product experience for the end user, the go-to-market advantages incumbents maintain in the traditional world of enterprise sales fade away. Not only is the recipe for a winning product in bottom-up enterprise adoption the same as in the consumer market, but the actual mechanics of growth are similar. If the end user is the decision maker, consumer-style growth tactics are often the only way to get their attention. Building viral loops into the product, understanding which marketing channels matter, building a brand users trust, cultivating community around the product, and supporting a user journey that makes it easy to adopt (and pay!) become table stakes.

Growth+Sales in reality: common failure modes

If all goes according to plan, you flawlessly layer top-down sales on bottom-up momentum, unlocking their symbiotic accelerants without running either of them. But the reality is that it’s hard enough to get one go-to-market motion right… and now you want to take on the complexities of two? AND synchronize them successfully?! If the growth+sales playbook is right for your company, the path to market ahead is full of hidden traps. While many elements of the company-building journey may be out of your control, the most common failure modes in growth+sales are avoidable with the right tactics.

Failure Mode #1: Forcing the growth motion when it doesn’t fit the product – Before even starting down the growth+sales journey, make sure it’s right for your startup. Is the out-of-the-box value proposition to the end user sufficiently compelling for them to adopt on their own? Can end users adopt without a heavy-touch implementation process that requires engineering resources to integrate?

In products that require access to secure business systems authorized by centralized IT, insurmountable technical constraints may squash the opportunity for bottom-up adoption. Similarly, systems of record that sell into specific functions are relatively useless to the end user unless their entire department rips out the old system and migrates entirely. Attempting to execute the growth+sales playbook on a product that will flop on bottom-up adoption can keep the go-to-market engine from ever taking off at all.

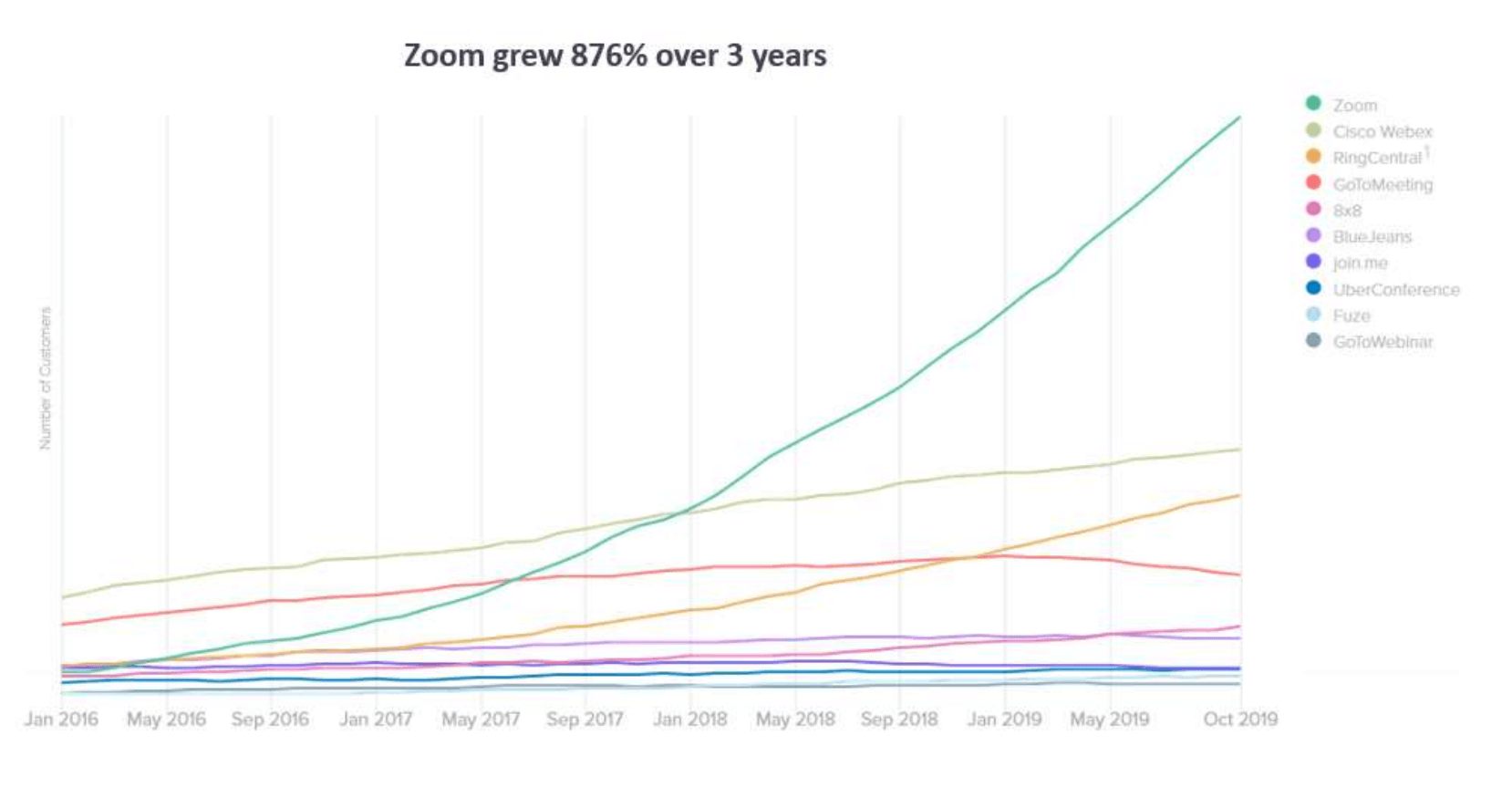

On the other hand, attacking a market ripe for bottom-up adoption with the right product can yield amazing results, even in categories historically dominated by top-down sales. Zoom is the popular success story of an “it just works” product victory, rapidly scaling enterprise penetration on top of a freemium business model and a product that starts simple but earns the right to be complex.

Source: Zoom FY 2020 Earnings Presentation (March 2020)

Charts provided herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision; past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Failure Mode #2: Buying end user mindshare that doesn’t spark organic love for the product – If organic adoption is the holy grail for bottom-up adoption, then paid acquisition channels that yield low-retaining users is the addictive drug that will ultimately kill a distribution model. As enterprise startups progress deeper into the adoption curve, from early fanatics who obsess over the product to late adopters who aren’t willing to put up with bugs, acquiring new users via paid channels tends to only get more expensive. This is particularly dangerous when the resources allocated to paid channels don’t actually convert into users who love the product. Then you’re stuck with unit economics in an irrecoverable state as well as a direct sales motion that is no more efficient than if you had never attempted the growth motion in the first place. If you try to layer enterprise sales on top of underwhelmed end users, you’ll undoubtedly face underwhelming results. Before undertaking paid user acquisition, make sure that the end user truly loves your product. Or else, the users you buy won’t either.

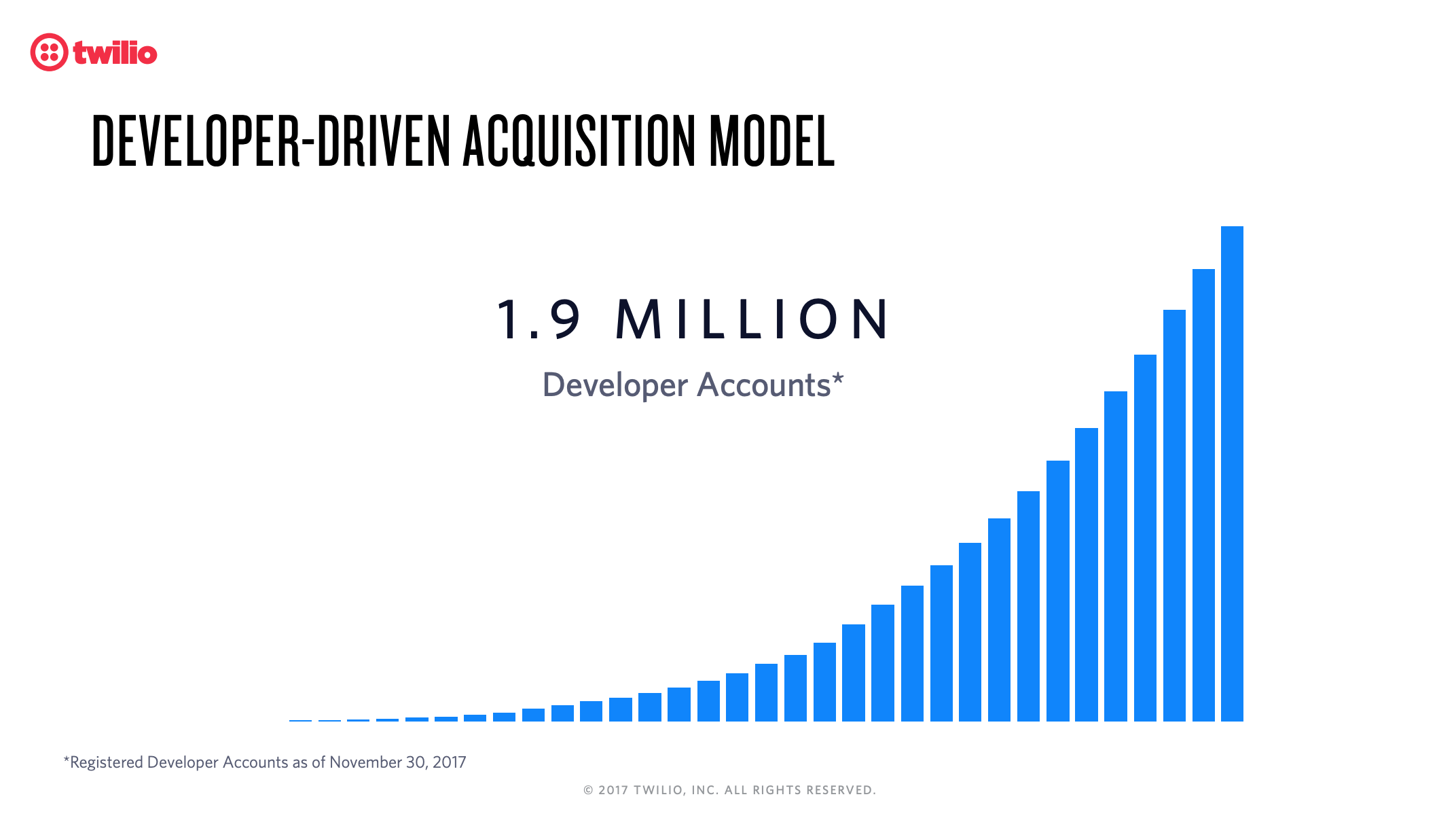

Twilio is a compelling case study in how to authentically win the battle for user mindshare. From day one, Twilio relied upon a developer-first motion… “acquire developers like consumers, enable them to spend like enterprises“. As with many developer-first growth motions, you can’t win end user mindshare via paid user acquisition. What matters the most is the quality of the underlying technology. And then proving it to the developer community. Twilio won the developer mindshare, becoming the technology, and ultimately the brand, that developers trust. Winning the mindshare battle is no easy feat, but it is extremely hard to compete against once established.

Source: Twilio Analyst Day Presentation (December 2017)

Charts provided herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision; past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Failure Mode #3: Using traditional metrics to measure a new motion – In the traditional enterprise motion, the most instructive measures of success are aggregated at the customer-level or summed across the entire customer base (ie, ARR, ASP, seats, etc). But traditional sales metrics aren’t sufficient to understand how well the growth motion is working. Instead, look to consumer-style metrics that track active user growth (MAUs, WAUs, DAUs), engagement (session length, days active in a given work week), active user retention, and funnel conversion points throughout the user journey.

Even better, see how these behaviors vary by user persona to really understand the adoption journey within a customer. You could easily see paid user seats and unique logos in your customer base showing signs of great success in top down enterprise metrics. However, upon looking under the hood, evidence that only a fraction of the paid seats are actively using the product is a warning flare that the growth motion isn’t actually generating sustainable active users. Don’t be surprised to see a tidal wave of churn on the horizon when the next renewal period hits.

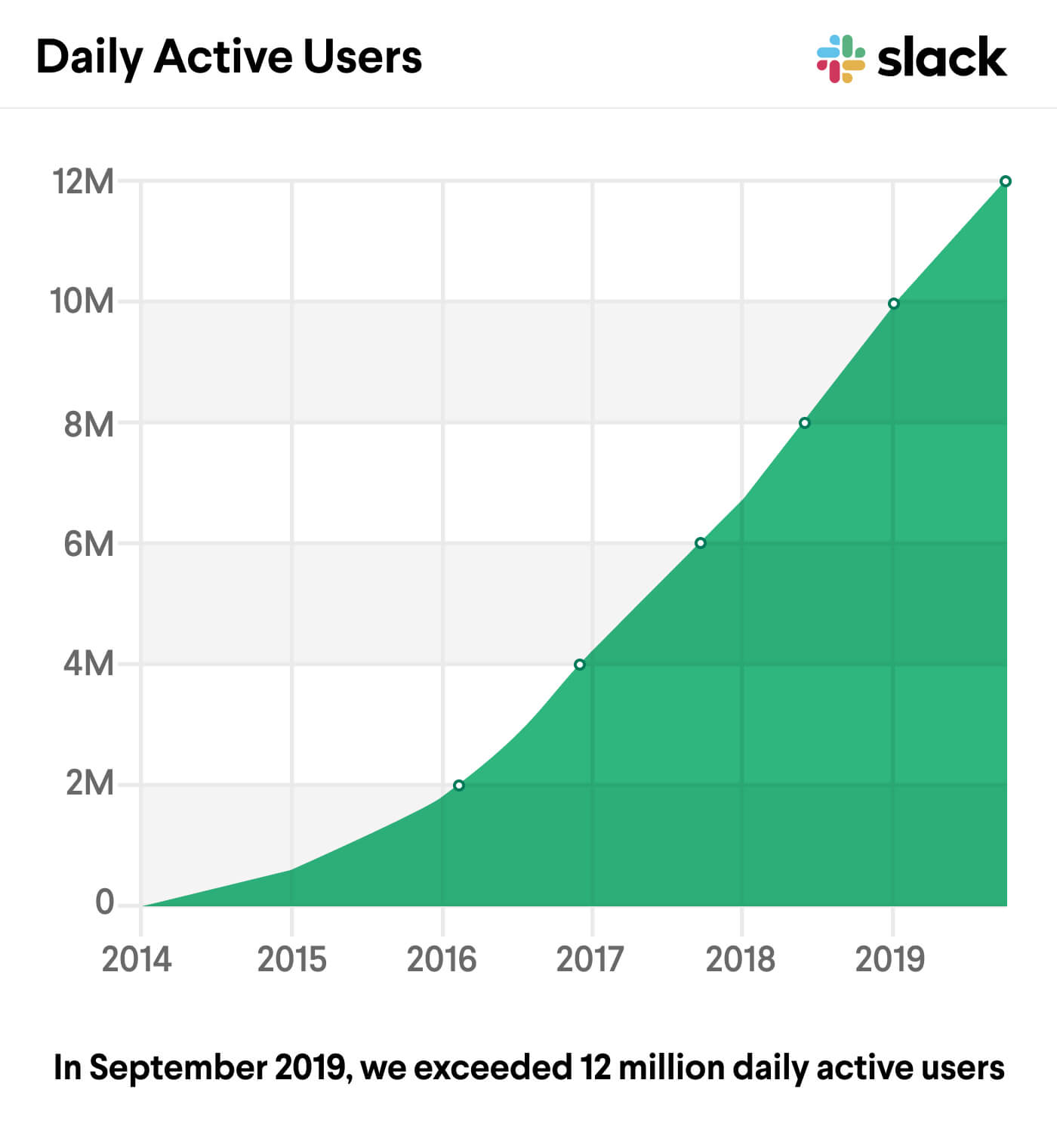

Although revenue is the ultimate evidence of the market finding value in your product, in growth+sales it takes a much deeper look into the user base to fully grasp the potential for the top-down sales motion. For instance, it’s interesting to see Slack’s revenue trajectory across all the customers, but it’s way more interesting to see the intracompany network effect at play within new customers as a predictive path towards full deployment within a logo (and the revenue that comes with it!). What you can’t see in traditional sales metrics is the conversion funnel from organic adoption on a free product with just a few seats all the way to wall-to-wall penetration, from the front line employees all the way up to senior management. Nor can you see all the engagement data that shows a customer isn’t going anywhere! In the era of growth-sales, DAUs often tell us way more about which products are victorious than any backward-looking revenue metrics.

Source: Slack Newsroom (October 2019)

Charts provided herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision; past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Failure Mode #4: Layering on sales too early – If you layer on sales too early, not only does the organic motion never mature into efficient sales, but you end up with two different pitches to two different buyers – one where the customer knows you, and one when they don’t – and very little bridging them together. In the first pitch, you sell the product experience to the end user. And in the other, you make a sophisticated ROI case to executive decision makers and technical buyers. In this scenario, you take on the executional complexity of both go-to-market motions without any positive relationship between them.

If you don’t have the headcount capacity, internal systems, and mental calories to execute both motions concurrently, sequencing them too early could even do damage, prematurely killing any organic momentum. Thankfully, you will likely start to see evidence of the market pulling you into the top-down sale when the time is right, as users ask: “How can I get this in the hands of my entire department? How do we unlock all the premium features? Can you talk to our IT department to get this rolled out to my entire department? Why isn’t everybody using this?!”

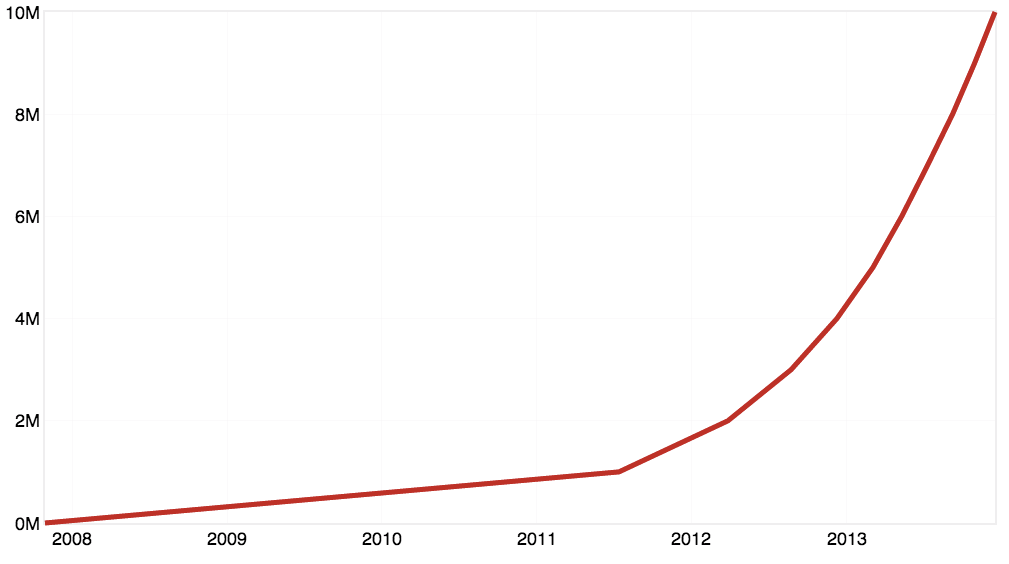

Going back to the early days of GitHub well before the enterprise motion took off, GitHub gave the developer community the room to organically converge on GitHub as the best code repository. The repository growth curve through 10M+ reported in December 2013 demonstrates the power of this organic growth vector, which may never have been catalyzed if GitHub had attempted to manufacture the same growth with enterprise sales too early in the journey.

Source: GitHub Blog (December 2013)

Charts provided herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision; past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Failure Mode #5: Growth momentum that doesn’t actually make enterprise sales any easier – In some cases, organic user presence doesn’t actually reinforce sales, regardless of how hard you try. Perhaps the growth motion doesn’t actually connect you to the right buyer, which is a common dead end in open source. Or bottom-up adoption cannibalizes your opportunity for the enterprise sale if the users are perfectly happy with the basic tier without ever paying up for premium functionality. This situation is the most dangerous when the growth motion is forever optimized for user volume without ever unlocking revenue. If the freemium model unlocks no promising path to the enterprise sale, turning your product into a viable business is going to be tough.

Failure Mode #6: Neglecting the growth motion once sales takes off – Growth+sales is not about doing growth first, and then growing up to sales without ever looking back. It’s about delivering on your promises to the user, then making new promises to the enterprise buyer without forgetting about the user. You don’t change your priorities; you sign up for new ones. Unsurprisingly, the stakes of getting this wrong are high, and often irreversible. You could hear sales reps hitting the celebratory gong all day, but in the background, feature innovation in the product slows down, the UX falls behind modern design paradigms, and the brand that was so hard to organically earn gradually erodes. The product that appears to be firing on all cylinders in the sales motion becomes exposed to competing attack vectors on the growth motion. End users regress to a state of unhappiness with your product (the new incumbent), and again vote with their feet on the new tool that better solves their problems. It’s critical not to forget about the growth motion after layering on sales, or you’ll be in the same treacherous position as all the top-down incumbents you knocked out in the first place.

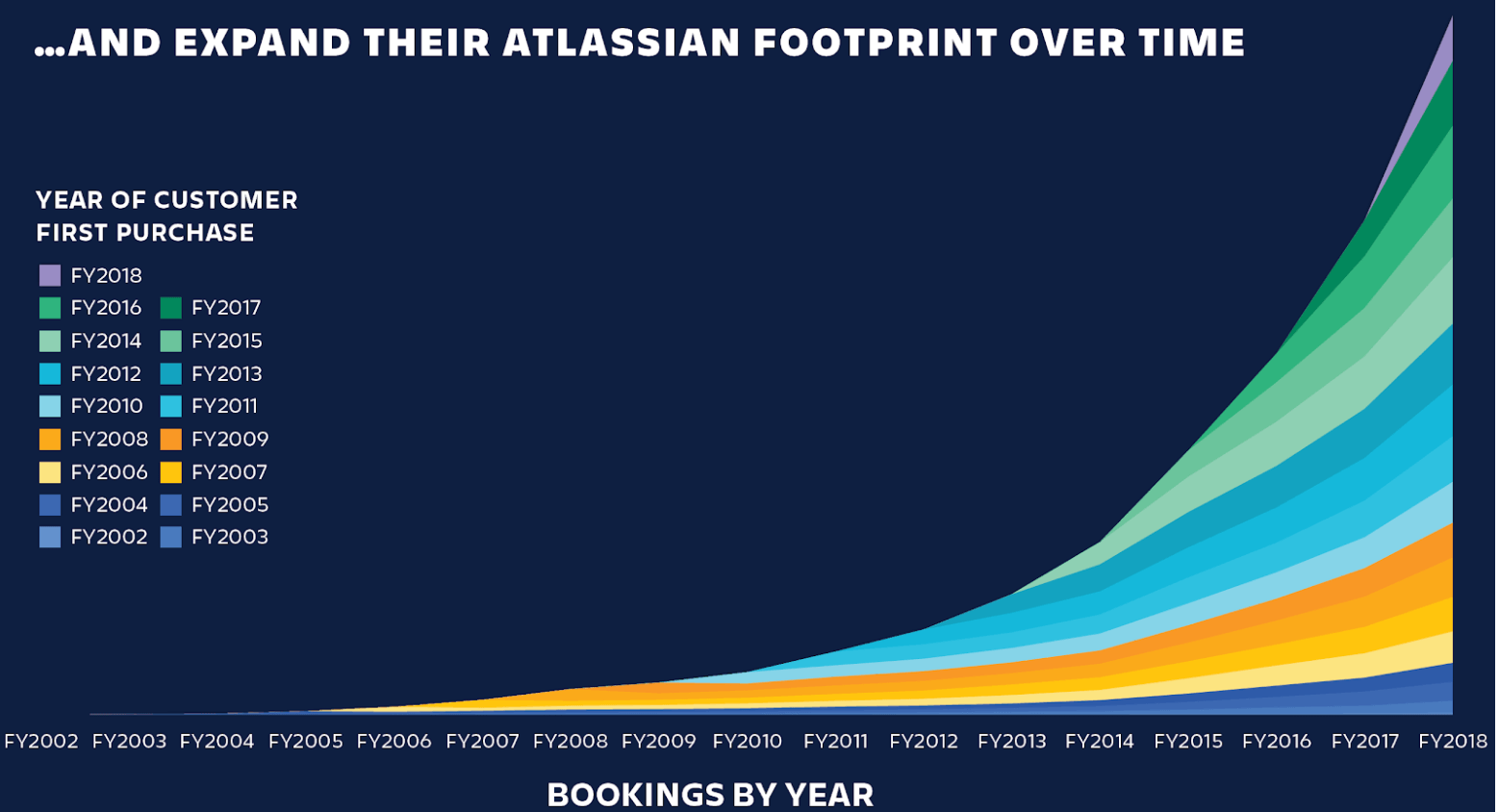

After first nailing the growth+sales motion on Jira and Confluence, Atlassian continues to expand addressable customer budget on the same growth+sales motion by delivering more value to the same customers, both via inorganic growth as a prolific acquiror (eg, Trello, HipChat, OpsGenie, AgileCraft) and by organically adding surface area to the product suite. Each new product unlocks a new growth curve within the same customer with another opportunity for top-down sales. This unlocks the impressive customer net retention behavior that growth+sales can sustain for multi-product companies over decades. Of course, now there’s an entire new crop of startups aiming growth+sales right at Jira!

Source: Atlassian Investor Presentation (April 2019)

Charts provided herein are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision; past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Advantage, startup

Given the many failure modes of the growth+sales motion, successfully running the playbook is no trivial feat. However, there is good news. As treacherous as the go-to-market journey may be for startups, adapting to the growth+sales era is near impossible for the top-down sales incumbents!

There will always be success cases in growth+sales that haphazardly fall into place to serve unpredictable, explosive organic demand. And that’s an amazing situation to be in. But for most startups, being thoughtful about the growth+sales motion gets your product in the hands of as many happy customers as possible in the long run.

Over the last decade, the handful of enterprise startups that figured out growth+sales early grew into some of the most iconic software companies of this generation, and now a new set of companies are well on the way to becoming growth+sales success stories. The same way that SaaS created a window of new company formation in the 2000s, we’re still in the early days of growth+sales as the dominant attack vector on enterprise incumbents, unlocking new categories throughout the 2020s and beyond.

-

Peter Lauten is a partner on the Growth investing team, focused on enterprise software companies.

-

Martin Casado is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he leads the firm’s infrastructure practice.