Many of the most consequential projects of the internet era — from Wikipedia to Facebook and bitcoin — have all been predicated on network effects, where the network becomes more valuable to users as more people use it.

As a result, we’ve become really good at analyzing and measuring network effects. Whether it’s decreasing customer acquisition costs, increasing liquidity, or improving retention, the metrics for identifying strong and durable network effects appear to be fairly well developed.

And for many types of companies, this is true. Standard marketplaces, payments networks, and a lot of social platforms can be easily sliced and diced using these tools.

But it’s also true that for a number of companies, the conventional frameworks break down.

There are a lot of companies that have (or will have) strong network effects, but you won’t see them in these standard metrics. Their numbers won’t help you measure, track, or even identify them.

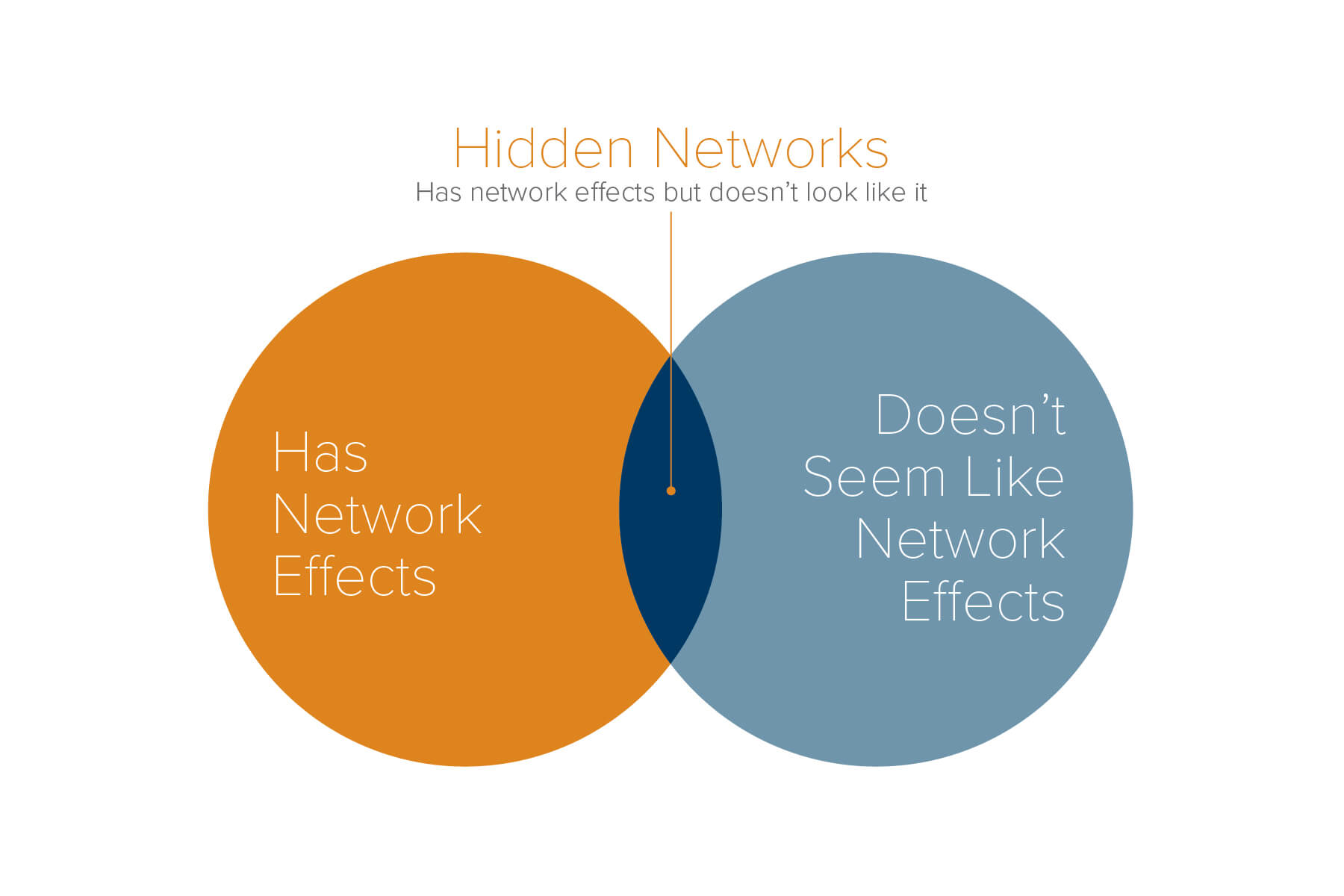

Their network effects are real, but they’re hiding in plain sight.

So why does this matter? Companies with network effects that don’t look like network effects are diamonds in the rough. Because their networks are hard to measure, they can often be under-appreciated in the short run and disproportionately strong in the long run.

In the same way that the best startup ideas are good ideas that initially sound like really bad ideas — because the obviously good ideas are both picked over and hyper-competitive — some of the strongest network effects companies end up being strong precisely because they initially don’t seem to have strong network effects.

Having network effects that don’t look like network effects can create unique advantages that can set a company up for long term success.

Most important is how this can affect the competitive landscape. If the value of the network isn’t quantitatively obvious in the early days, then these teams and markets can get less attention and fewer copycats trying to build a similar product and overlapping network. This gives founders more time and space to build their product and networks in an efficient, sustainable, and defensible way. Think of what the rideshare or restaurant delivery companies might look like if they had had years to build out their networks (and their competitive advantage) before the competition arrived.

While hidden networks have unique advantages, they also have their specific challenges that founders will need to navigate. Raising capital is harder with a theory of network effects rather than data, time horizons are usually longer and more uncertain, and the eventual strength of the network effects can be more ambiguous.

So what is a hidden network? Here are three(-ish) examples of networks that don’t look like networks.

1) Slow networks

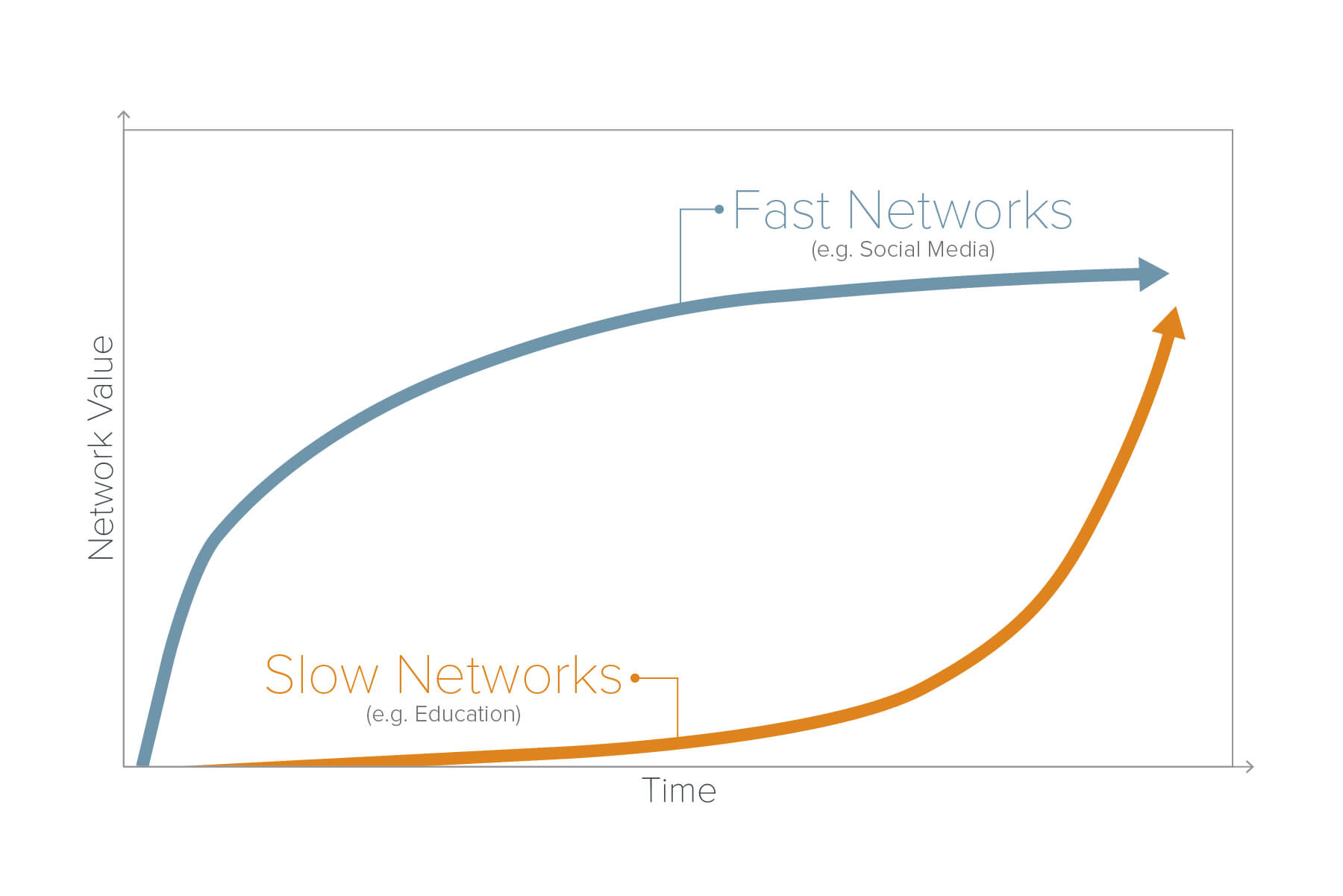

Slow networks are defined by a time delay between when the network is created and when it starts to show value.

Slow networks usually have long product usage loops and/or infrequent cadences that slow down the network effects. In contrast to fast networks, people often undervalue slow networks because the benefits aren’t immediately tangible.

A slow network can take years before its network effects begin to show, even if the company itself is growing quickly. In fact, some of the fastest growing companies today have slow networks.

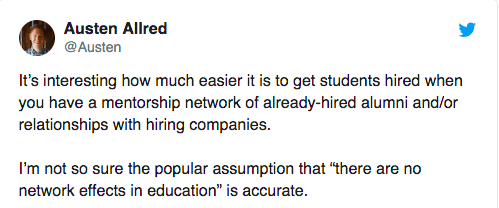

Take Lambda School, a full-stack education platform and one of the fastest growing startups today. Lambda offers a coding program funded by income share agreements, and they also work to help their students find jobs after graduating.

In theory, it’s easy to understand the network effects in Lambda School. As they get more (and better) students, they should be able to (1) find more employers who want to hire Lambda grads and (2) build a deeper network of Lambda alumni for recent grads to lean on, learn from, and get hired by. This flywheel brings more, better students into the top of the funnel and eventually more, better employers to the end of it.

Network effects slam dunk, right?

Well, Lambda is a 30-week program, after which graduates find a job. Let’s assume it takes an employer an additional few months to figure out whether their first Lambda grad was a good hire. At this point, it’s already been nearly a year to close that single loop. A promising candidate hears about that student’s experience, but it may take them a few more months before they’re able to enroll. At which point, it’s another 7-10 months before that loop closes and another employer can see the value.

It’s years before the true value of the Lambda network begins to reveal itself. That’s a slow network at work.

The advantage of slow networks is that once built, they’re usually very difficult to displace. The top universities took hundreds of years to build their network effects, and despite periodic predictions of their demise, these networks effects don’t seem to be showing any sign of weakening.

Another example of a slow network is social lending. When my co-founders and I started Frank — a social lending platform — we assumed it would have strong network effects. We were building networks of people that would lend to and borrow from each other, so the more people each user was connected to on the platform, the more valuable the platform would be.

Obvious network effects, right?

Since borrowing money happens relatively infrequently (about once every three years for our users), there was a multiple year lag between when a node was added to the network and when that additional node brought value to other users. Three years is a lifetime for a startup. While we were planting seeds, our slow network meant our biggest challenge was figuring out how to survive for years in order to see them bloom.

Lending and education often have slow networks, but it can just as easily apply to other categories like hiring, healthcare, or real estate, where feedback loops are long and the user cadence is infrequent.

Testing whether there are slow network effects is more art than science. In the early days, these companies often look more like linear businesses rather than network ones. But even if it doesn’t measure out as a network effects business, it might just be a slow network. A good test is if it (1) has all the features of a network effect business (e.g., more nodes makes the product more valuable), and (2) long product loops or insufficient saturation. If so, then it’s worth taking a deeper look.

Once you’ve identified a slow network, it’s important that everyone — founders, employees, investors, users — have the patience and resources necessary to let the network come to fruition. Slow networks often fail not because the network effects aren’t there, but because companies can’t hold on long enough to see them through.

2A) Unfinished networks

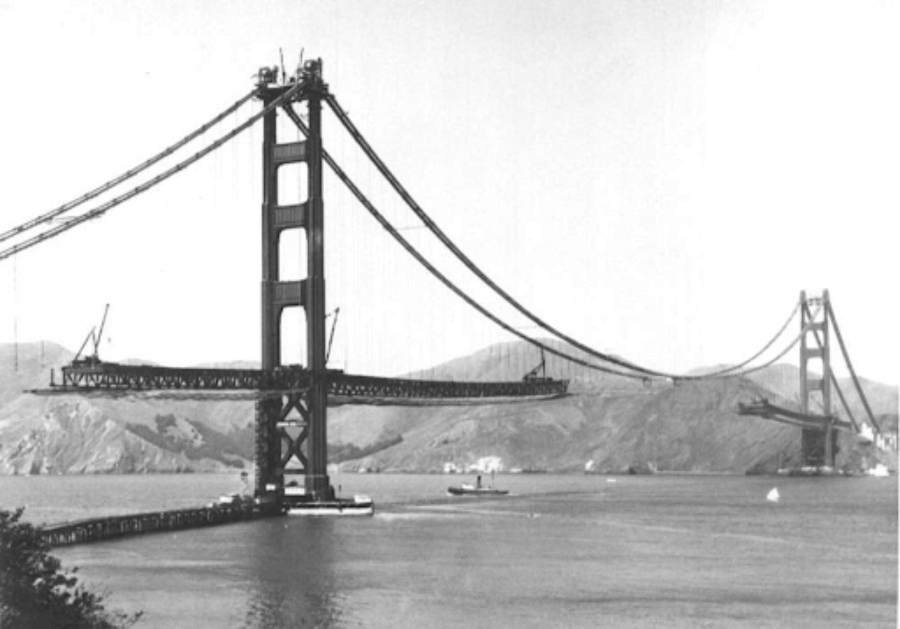

An unfinished network is one where a product feature or strategic decision leaves the network temporarily incomplete in some material way. When the network is eventually completed though, the network effects are immediately clear.

An unfinished transportation network 🙂

Like a slow network, an unfinished network will have bottled up network effects, but they won’t show up in any analysis or metrics.

One successful example of an unfinshed network from a few years ago was OpenTable. In its earliest days, OpenTable looked more like a SaaS business than a network effects one. Restaurants paid OpenTable $200 per month to let them take reservations online and embedded the OpenTable widget on their website.

Pretty straight-forward business. Definitely no network effects to see here, right?

As OpenTable built up enough restaurants, it created an opportunity for itself to be the easiest place for diners to discover restaurants, too. Once they had enough restaurants, they were able to invest in their consumer-facing products, like their website and apps that help consumers find restaurants, and thus, they completed the network. More diners = more restaurants = more network effects.

For perspective, OpenTable spent its first five years of existence primarily focused on signing up restaurants. They needed about 10% of restaurants in any particular neighborhood before the consumer product was good enough to use, and then the network could be completed.

Taking OpenTable’s network effects at face value during those early days would have missed the forest for the trees.

The challenge, of course, is that unfinished networks often don’t get completed. The start-up graveyard is filled with companies that thought they could flip the switch to complete their network but didn’t. This is especially risky when the completed side of the network is the supply side. Most businesses and workers will sign-up for anything that brings them business, so understanding which part of a network you’ve built and how difficult it will be to complete the full network is critical.

The key variable is whether there is emergent behavior on the incomplete side of the network. Are users trying to pull your product there? Are they trying to complete the network? If so, then there’s a good chance you’ve got an unfinished network.

2B) Throttled networks

A throttled network is one where a product feature or strategic decision limits the size or engagement of the network in a material way, thereby masking the strength of the network effects.

This is the cousin of an unfinished network in that both are kept small, but while an unfinished network is missing a critical piece, a throttled network is complete but limited. Like an unfinished network, a throttled network appears to have limited network effects — until all of a sudden, it doesn’t.

One example is executive networks. Chief is an executive network for women. Think of it as Young Professionals Organization (YPO), but focused on women in the C-suite. It’s still in its early days, but Chief membership is primarily structured around (1) a monthly coaching session/group discussion with a curated group of peers and (2) access to a salon series of events and talks.

They’re clearly trying to build a strong and valuable network. As more qualified women join, the community becomes more valuable. But you won’t see it in any of the traditional metrics.

In a network effects business, you’d expect to see CAC decline. But because Chief is intentionally limiting their membership right now — they curate and qualify everyone who gets in and have a long waitlist — their CAC is not a great indicator of the network effects. You’d also expect to see their network effects in increased engagement. But their engagement model is currently fixed at one group session every month or so, so there’s no opportunity for increased engagement. You might see leading indicators in the quality of the applicants/members or NPS scores, but these can be fuzzy and imperfect measures.

In the short run, Chief’s network effects seem non-existent. But in the long run, they might unlock the value of their network through increasing opportunities to engage, pricing that rises with network value, or even a deeper membership pool. The eventual manifestation of their network effects will depend on what the founders believe works best for their product, but it doesn’t take a huge leap to see the potential.

In some ways, Facebook was a throttled network in its earliest days. Initial users had to have a Harvard email address to join. This was methodically extended to others with a .edu email address, and eventually everyone else. This is the definition of a throttled network. While Facebook didn’t limited the engagement on the site — which made the network effects a little more obvious — it did intentionally limit the scope of the network.

It’s an important distinction to separate throttled networks and exclusive ones. Throttled networks are, in a certain sense, temporarily small. The value proposition can support a larger network, just not yet. In contrast, networks that rely on exclusivity — dating apps like Raya or members clubs like Soho House are a couple of examples here — often have an upper limit to their network effects.

Throttled networks are sometimes kept small through a conscious decision of the founders, a temporary technical or operational constraint on the business, or even a short-term regulatory control. Sometimes it’s unintentional, and the network is throttled via poor execution or weak technology. If it appears that the thing that’s throttling the network is addressable, this is usually a good sign that the network is far more valuable than it appears.

The test for telling whether it’s a throttled network with strong network effects is fairly straight-forward: understand what would happen if one of more of these constraints (e.g., price, network growth, engagement, etc.) were relaxed. If the answer is positive or neutral, then it might be a throttled network just waiting to be unshackled.

3) Latent networks: (aka “Come for the network, stay for the tool” networks)

There are a host of companies that build the tool or product before they build the network. Delicious (with bookmarks) or Instagram (with filters) are the classic examples of a “come for the tool, stay for the network” company. But there are also companies building the network before they build the actual product or tool. Think of this as “Come for the network, stay for the tool.”

These companies can be especially formidable because no one understands the power of what they’re doing until it’s too late to compete.

The concept is that you start by building a community that acts like a network, with users interacting, engaging, and generally creating value for each other. Eventually, a product is introduced that catalyzes or amplifies the way the network engages. Before the product arrives, there isn’t anything measuring or monetizing the network, so it can be difficult to really see the strength and potential of these networks.

Savvy game developers have been following this playbook for years. Even before there is a game to test, they’ll set up a Discord server to help build the community and network of gamers. Most importantly, this ensures there is a vibrant ecosystem when the game launches, which is important in social games where having other players materially improves the experience. Hypixel and Phoenix Point are a couple of examples where they started by building robust communities that eventually became (or will become) the networks that are layered on top of the games.

These latent networks are the hardest “hidden network effects” to both predict and execute. Often times these communities are actually an audience rather than a latent network, meaning users derive value from the central node, not the network. When it’s just an audience, the tool or product ends up scaling more like a linear business (e.g., a DTC product) than a network. Differentiating a product-less network from an audience is very difficult. Many a celebrity entrepreneur has believed they had a network that wanted to engage with each other, before realizing that what they actually had was an audience that just wanted a piece of their celebrity heroes.

So what’s the test to tell whether there is a latent network waiting to be activated? A network engages, an audience consumes. Look to see if the network’s users are engaged with each other or just the central node. Ask yourself who is getting additional value when someone new enters this community. If it’s all (or at least some) of the community members, then it’s a network. If it’s just the central node, then it’s probably an audience.

Hidden networks are hidden advantages

While they have their own unique challenges — primarily that they often need more patience, conviction, and capital — hidden networks are, in my opinion, the under-appreciated type of company that everyone should consider starting, investing in, and working at.

At the end of the day, building a network effects business is essentially a race. One company is trying to get to that magic tipping point before their competitors. That’s why a hidden network effect can be a big benefit for an entrepreneur willing to bet on their network effects.

Imagine if you got to start running before anyone realized the race had begun. That’s the advantage of hidden networks.