This interview was recorded earlier this year and originally appeared on The Observer Effect; it has only been lightly edited for formatting here.

On productivity

Let’s get into it. Over a decade ago, you wrote a famous post called the ‘Pmarca guide to productivity‘. What is the 2020 version of the Marc Andreessen guide to productivity?

The big thing is I’ve basically done a complete 180 degrees off of the model that I had from 13-14 years ago. A lot of that was just driven by starting and then scaling this firm. At this point we have a large number of companies in the portfolio and a large number of investments in the works at any point in time. The sheer load of the number of things coming at me and coming at the senior partners here is just very intense. That has forced a comprehensive shift to a far more structured way of living. It’s actually by far the most structured I’ve ever been.

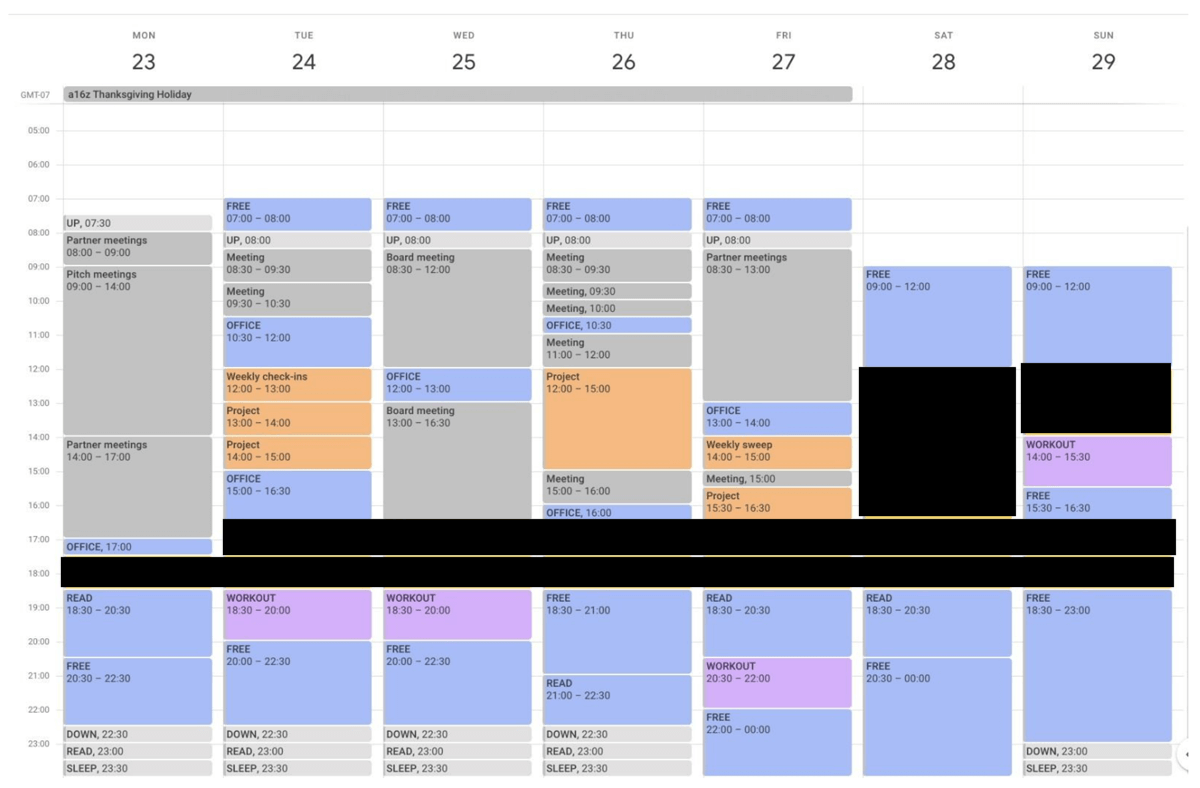

The typical day for me right now is quite literally following the calendar very closely. I’m trying to have as “programmed” a day as I possibly can.

Walk me through what a day looks like.

I should start by saying that none of what follows would be possible without the help of my amazing and indefatigable assistant Arsho Avetian. She’s been my secret weapon for more than 20 years.

It’s more by week than by day. The day of the week determines a lot. Monday and Friday have very specific schedules because we run in the rhythm of a venture capital firm. There’s an all day sort-of marathon on Monday which is when most of the actual teamwork happens. We also use Friday for that. Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays are much more open ended. Those tend to be a lot more outwards-facing and have lots of board meetings, entrepreneur counsels and so on. Running Monday through Friday in this kind of regimented schedule, I do now finally understand why people have the concept of a weekend. I’m trying my best to preserve Saturday and Sunday for at least a little bit of downtime.

In your old post you talked about Arnold Schwarzenegger’s open calendar and the upside of having unstructured time in your day and the flexibility you get with that.

When Arnold did that interview I think he was in “entrepreneur mode”. At the time he was engaged in lots of entrepreneurial projects and starting lots of new businesses. I think there’s certainly virtue to that if you’re an entrepreneur in heavy creation mode.

I lived a fair amount like that earlier in my career when I was programming. Basically working on exactly one thing all the time until you’re exhausted and collapse. And then get up the next morning and work on that thing some more. I never really had a calendar. I just knew what I was working on. In a sense, that’s the same as having no schedule.The challenge obviously shows up when you’re trying to do anything that involves either running an organization or being in a customer service role. That is how we think about parts of what we do now. If part of your job is to deal with a large amount of incoming, you actually need to respond in a timely manner and not let people down. Maybe some people can do that off the cuff. I don’t know how to do that.

Was there a moment when you decided to change your old system? Was it when you founded the firm?

Yeah, honestly, when we started the firm in 2009 we just got right into it. It was just a hurricane of new activity. We had decided one of the values of the firm is respect for the people we work with. And part of that respect is — we don’t drop balls. We respond quickly and we have SLAs on getting back to people in a specific period of time. We use the old JP Morgan saying of “first class business in a first class way”. If you contact us, you’re going to get a response. If we commit to doing something, we’re going to do that thing. It was just a necessity to be able to have some sort of system.

Venture capital, I think, is very “close to the ground” work. The VCs who have tried to abstract themselves from the day to day have not done well. You have to really know what’s going on. You have to really be in close touch with what’s happening in these markets and with these technologies and where these entrepreneurs are. And you have to be talking to a lot of people all the time, right? It just necessitates a more structured approach.

You’re waking up on Monday morning, or on a Sunday night, you’re looking at your calendar, what are you thinking?

I’m thinking “God, I’m organized! I have a plan!”. If I didn’t have this, I’d be in a panic the very first moment I wake up.

The big thing is basically *everything* is on the calendar. Sleep is on the calendar, going to bed is in there and so is free time. Free time is critical because that’s the release valve. You can work full tilt for a long time as long as you know you have actual time for yourself coming up. I find if you don’t schedule enough free time, you get resentful of your own calendar. When I was younger, I didn’t really have the concept of turning off. But there comes a time, a little bit with age, when your body rebels. And obviously, if you have a family, that’s not great with a system where you’re just always working.

The value of open time and delegation

One of the things I find interesting about your calendar is that there is a lot of allocated open space. We’ve often spoken about how some of the most interesting, influential people in the world tend to have large chunks of open space. As opposed to executives who are scheduled for every 30 minutes back to back from 8am to 7pm.

You know, we’ve both worked with executives where they were scheduled to the ‘nth’ degree. The three things you tend to notice with executives like that.

One, they just never have any time to actually think. And that turns out to be a fairly important thing.

Two, they have a hard time adjusting to changes in circumstances. In our business of venture capital, you get a lot of problems that come up. There is a lot of firefighting. It’s like those classic movie scenes when there’s a huge crisis and somebody calls out to their secretary “Cancel my schedule!”. Well, maybe you wouldn’t need to do that if you had some flexibility in your calendar.

Then the other thing you’ve probably seen is the managers who are regimented to that degree end up being micro managers. You’ve probably seen examples of this where some of these folks end up in the weeds on everything. The good news is they’ve got the pulse of everything happening in the organization. The bad news is they’ve become the bottleneck. The extreme form — and I’ve worked with a couple of people like this — end up having a long line outside their office. The lines will stretch waaaay down the hallway with people waiting to get in and see them. They kind of bottleneck your organization too. It’s demoralizing to work in an organization like that because basically, whatever that is, it’s the opposite of delegation.

A related topic is delegation. For a lot of those folks, it’s hard to let go. Delegation can often be a platitude. It’s easy to talk about but in practice a lot of people struggle with it. So when you want to clear up open space on your calendar, how do you do it? How do you *actually* say, “I am not going to do this”, “I’m going to say no”, or “I’m going to have someone else do this”.

Yeah, well, the good news is because of the way I run things, I don’t directly manage anybody.

You’re a very unusual person for me to do these sets of interviews with because you’re not a traditional CEO running a huge organization.

That’s right. So that’s necessarily going to be different, at least to some degree. I don’t have the pressure of all of the one on ones, all the management responsibilities. I’m involved in a fair amount of management stuff for the firm but it’s stuff that we cover in our internal meetings. And then we’ve got all these incredible people to manage all these teams.What we all kind of have to do at some point is to figure out how to just say no and triage the incoming.

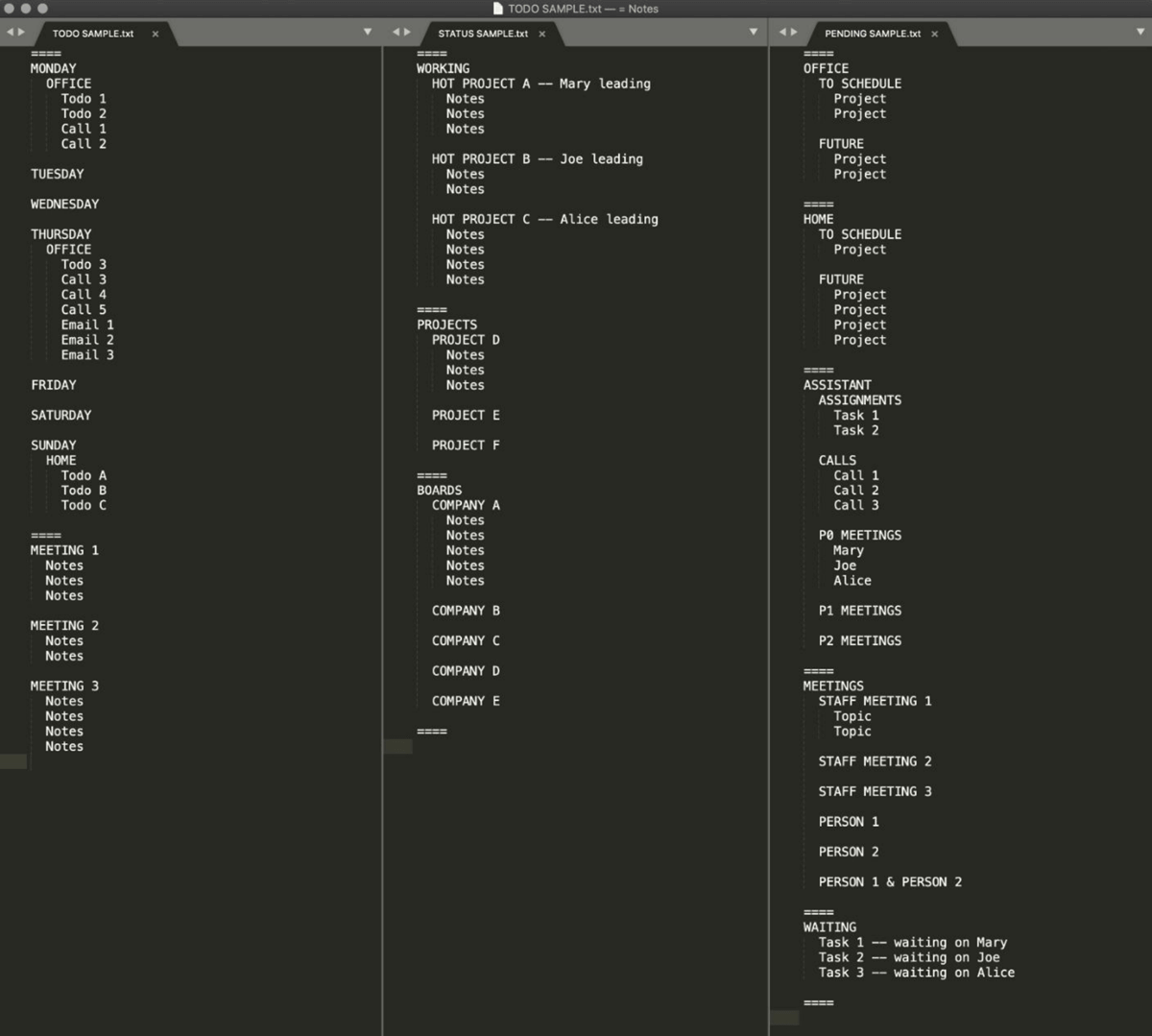

Which may be good segue to these text files that you sent me a screenshot of. Every executive has to have their own check-in system. You have finite time and you have a bunch of projects you care about that you need to keep an eye on. What’s your system to make this work?

So basically, there’s two kinds of projects. Apple has this concept they call the directly responsible individual, the D.R.I. For any project, I’ve tried to identify the DRI. Who is the person responsible for delivering the project? If that’s me, then the project itself gets on my calendar. If it doesn’t go on the calendar, it is not getting done. The weekly check in is for all the projects other people are responsible for. As an example, you could have a company raising money or going through a big transaction. I don’t want to hound the entrepreneur or the CEO every day necessarily but at least want to stay up-to-date on a frequent basis, right? I never want these things to just go dark where you’re going “Whatever happened to that?”

Goals and systems

I want to zoom out just a little bit. Talk to me about a longer time horizon, say at a yearly level. Is there a week where you’re off meditating on top of a mountain and saying “Well, this year I need to spend more time with founders” or “This year I need to spend more time reading scientific papers” or some such allocation. And tied to that, how do you connect your goals and the firm’s goals to how you spend your time and attention? Is there a mountain top?

<Laughs> There’s no mountain top dammit! Keep me off the mountaintop! No mosquitoes. No, no, none of that. So a couple of things happen. One, about every six months or so I feel overwhelmed. It all starts to kind of get away from me. And so typically about every six months, I’ll basically sit down and do a come-to-Jesus with myself. Which is “Okay, you’ve got this great system, but it’s becoming overloaded”. And “you’re saying yes to too many things and are involved in too many things”.

You really have to uplevel and figure out what’s important. I usually take a good hour to look at what I’ve been doing. It’s basically figuring out the threshold for “yes” versus “no”. I try to revise that about once a year. Also about once a year, I rewrite my personal plan. I just write from scratch what I’m actually trying to do and my goals and then line up the activities that are below that. I would say a couple things about time allocation. One, it’s not spreadsheet driven. You read about these executives/CEOs having this very complex exercise and they use a spreadsheet for their calendar…

Steve Ballmer famously used Excel for this calendar.

Yeah, exactly. And so they’ve got all these detailed analytics and pie charts and reports and all this stuff and if you’re running a Fortune 500 company, I can maybe understand that. You’re almost a head of state at that point. You’re trying to like time-slice between so many different constituents and you’re trying to hyper optimize every 10 minutes slot. I sympathize with the people who have that challenge. That’s a level of rigor that I’m not willing to go to.

I do try to have some sort of intuitive sense of what’s going on and how to rebalance. The firm is built to accomplish what I want to accomplish. And then my role here is to accomplish that within the context of the firm. And so the short answer is always the same — how do we optimize for the success of the firm? For the projects the firm is involved in, how do I optimize my contribution to that? So, you know, it’s been the same answer to the question every year for 11 years in a row and I don’t think it’ll change anytime soon. I think it’s more of trying to tune against a single goal as compared to trying to rethink the goals.

Process, outcomes, and bets

That’s such an interesting topic, because, as you know, there’s two schools of thought on how to set goals. Either on a personal level or at an organizational level. One is you use OKRs [objectives and key results] and metrics and you look at something very quantifiable to measure results objectively. The other school of thought is to just focus on the inputs and the process, not the actual results themselves. And to add to that, your job is unique in the sense that it has such a multi year long term feedback loop as opposed to a business unit with quarterly results.

Yeah, we’re basically all about inputs. It’s basically process versus outcome. And it’s exactly for the reason you said. Venture capital is too elongated an activity. We don’t really know whether something is going to work or not work in the first five years of its life after we passed. And so it’s — okay, what do I learn? Like, what, what do I learn in the first three years when it’s not working? Because sometimes these companies really struggle for a while and then they really succeed. Sometimes it’s the opposite — they really succeed fast and then they have serious issues later.

It’s really hard to get good metaphors but it’s poker, right? It’s really, really, really hard to be a good poker player. And if you’re kicking yourself every time you have a bad hand, the bad habits just simply happen. You just need to be able to have a system that lets you think through the process…

“Thinking in Bets” by Annie Duke is one of the best books on this.

Yeah, exactly. Michael Mauboussin has also written extensively in his books about this as a profession. The craft of investing as a process of separating process and outcome.We are almost entirely a world of trying to optimize the process. The outcomes come when they come 5, 6, 8, or 10 years out. At that point, I’m a skeptic when it comes to games where you try to look back and describe the causal relationship between the things that you did and the outcomes. It’s always uncertain and kind of sketchy.

It’s really hard to derive causal relationships.

Yeah, and so we really don’t spend a huge amount of time on that. What we’ve zeroed in on is — what’s the optimal way to run the process? What’s the optimal way to run the firm? What’s the optimal way to help the entrepreneur? By the way, the optimal way to help is not too much help. The optimal way is to make sure we understand what’s happening in the industry, what’s the best way to help with our network, the optimal way to help the management teams. It’s all a process.

Honestly, this also goes a little bit to my psychology — I actually don’t have the gambling gene. I get no rush from the bet or the result. I sit down for one of those and nothing happens. My pulse chemistry is just flat. And then the mathematical part of my brain is like, well, the expected return for this exercise is negative, what the fuck am I doing? And so it becomes unfun in the first 10 seconds and then I just walk away. One of the things in the firm is we actually don’t celebrate our successes enough. We don’t get enough of a rush out of actually winning. We’re extremely competitive but the payoff is not the point.

That’s a fascinating point because often people on the outside compare venture capitalists to gamblers when on the inside it’s incredibly different.

I would never be a professional gambler but one of the things you find about professional gamblers — they may play poker at night but what they do during the day is they hang out together and they make side bets for large amounts of money. And it’s literally a side bet of sitting in a diner and betting on whether there are going to be more red cars than blue cars passing by. What they’re doing is “steeling” their own psychology to be able to pull the trigger on bets like that with a purely mathematical lens and with no emotion whatsoever. They’re trying to steel themselves to be able to be completely clinical.And so as contrast, what they then hope for that night when they sit across the table from someone is to hope they’re dealing with somebody who’s super emotional. Because the clinical person is going to just slaughter the emotional person.

It’s this weird thing where it’s the kind of activity that should result in these wild highs and lows but the true pros are just indifferent. They don’t care because it’s a probabilistic outcome. That’s just part of the game and they’ll come back and they’ll probably be better the next day.

On books

I’m going to switch gears just a bit. I asked a lot of people we both know for questions for this interview. The single most common question: how do you read so much?

I’ve really read all the time since I was a little kid, it’s been a lifelong thing. It’s basically trying to try to fill in all the puzzle pieces for the big discrepancies.A great term is “sense-making”. Essentially, what the hell is happening and why? The world’s an incredibly complex and erratic place and trying to figure that out is kind of a lifetime occupation.

The thing I’ve tried to do the last few years is really “barbell” the inputs. I basically read things that are either up to this minute or things that are timeless–

They are Lindy [Effect] safe.

Yeah. I’m trying to strip out all the stuff in the middle. What I’ve discovered is the number of people who can write something in the middle zone — when they’re trying to explain something that happened last week, month, a year or even a decade — and who I trust to actually give me an objective read on the situation is just a really, really short list. There’s a handful but there aren’t very many.We have one situation currently — what’s literally happening right now [with COVID-19]. Coronavirus is one where everyday I’m looking at all the science and all the economics because these are critical issues. And I’m trying to avoid all the commentary and all of the interpretation.

And then the other, as you said, there’s just a very large amount of timeless stuff that really has been proven right over time. You could spend your entire life only reading timeless works which is what smart people used to do.

So how do you go from zero to one in a new space? Where do you start? Do you go breadth first or depth first?

Part of being a firm is — we get to know and talk to a lot of people. So a lot of it, honestly, is face to face conversations. Often the way you learn about something is because somebody tells you about it. So, the first thing is to be alive and alert in every interaction. And then somebody gives you big things/new areas. I call them “things from the future”. Something is happening in the world. It’s only happening in one place. But..wow, it’s something that might end up actually ultimately happening everywhere. I’ll often ask those people who else I can talk to or what I can read.

Every once in a while, something nice happens. When I ask what can I read, they say, “well, there really isn’t anything”. And that’s just the best case scenario because that means we might be the first to it. If it’s tech or business or finance, we basically cast inside the firm. It’s not me going off and doing a two-week deep dive but we’ll have one of the other people in the firm go off and do that work. We want to do that because it’s part of their own development and their role. It’s also an opportunity to educate us about the present.

In a recent podcast, Naval Ravikant talks about how he doesn’t finish books anymore. He let go of the guilt of needing to finish books. Tyler Cowen has said something similar. Do you finish every book?

Yeah, I really struggle with that. I have a whole bunch of books that I haven’t finished which I really should just toss. Patrick Collison talks about this too. The problem of having to finish every book is you’re not only spending time on books you shouldn’t be but it also causes you to stall out on reading in general. If I can’t start the next book until I finish this one, but I don’t want to read this one, I might as well go watch TV. Before you know it, you’ve stopped reading for a month and you’re asking “what have I done?!” I think that’s part of it. This moral hectoring of “don’t do that” which can only be so successful. The other technique is to read a dozen books at a time.

How does that work? Do you have a stack of books next to you at all times? Are you flipping through the Kindle app on your phone?

It’s a pile of physical books and then the Kindle books. And you’re reading them all at the same time. When you sit down to read, you just read the one that’s the most interesting of that pile. It turns out those are the ones that you finish. A month later, there’s a bunch that you’re theoretically reading and you’re on Chapter Three and you’re never gone back to it. That’s like having the shirt in your closet you haven’t worn in a year. It’s a signal to get rid of it.

On learning and alternate viewpoints

Michael Nielsen and Andy Matuschak talk about the power of ‘spaced repetition’. Some people go back and read the books just to absorb things better. Do you find yourself like going back and re-reading books at all?

I aspire to be that kind of person who does that but it’s not happening. I remember instructions. I don’t remember specifics. I remember ideas really well and concepts and explanations but fail on details. I fade on people, I fade on dates, I fade on contents of specific conversations.

I take a lot of notes though I’ve never referred to the notes later. I was reading this great book about memory. When you take notes, it’s actually like a double helping of memory, a double chance to remember something. The other book technique is from Chris Dixon. He thinks of chapters in books like blog posts. When he sits down to read, he goes and looks at the table of contents as a set of blog posts, Oh, those two look interesting already? And then you say — okay, I can throw the rest away. I’m not gonna read every post in the blog either, right? I’m only gonna read interesting ones–

This only works for non-fiction though–

Totally different process for fiction.

We’ll get to fiction another day. In an earlier interview, you spoke of how you’re delighted when you’re proven wrong. So how do you seek out alternative opinions?

This is like a big kind of self development. So, generally speaking, most of the people you’re around most of the time hate being told that they’re wrong, right? They absolutely hate it. It’s really an interesting question as to why that’s the case. The best explanation I’m able to come up with is: People treat their ideas like they’re their children. I have an idea the same way that I have a child and if you call my idea stupid, it’s like calling my child stupid. And then the conversation just stops. I’ve really been trying hard to do is to spend less time actually arguing with anybody. Because people really don’t want to change their mind. And so I’m trying to just literally never argue with people.

However, there *is* a group of people who do love to change their mind. And interestingly, it’s the people everybody wants to hate. It’s hedge fund managers. The really good hedge fund managers seem to all have this characteristic: If you get into this heated argument with them, they’ll actually listen to what you’re saying. They won’t always change their mind but sometimes they’ll go “Oh, that’s a really good point”. And then they’ll say, “Oh, thank you” which is just really weird for it’s not usually the result of an argument. The reason they’re thanking you is because they’re gonna go back to the office next morning to reverse the trade.

I think in some ways, that’s almost a function of the job where an alternate point of view is arbitrage, something they can monetize. In most typical leadership roles, your identity could be tied up, say, in the strategy that you’re running to build 1000 people on. So proving someone wrong — while the best thing for the organization — may not be great for that executive.

Yes. Hedge fund people are the ultimate example because they can literally change their trades every day. They can be long a company on Tuesday and reverse that later in the week. And they love throwing away old ideas — for exactly your point — it’s going to make them money. Sometimes internally it’s my goal to have that kind of mentality but It’s very difficult.

Well, if you want people who are going to tell you how wrong you are, you should get back on Twitter.

<laughs>

On improvement and motivation

Changing the topic, Tyler Cowen has this analogy he uses where he asks what’s the equivalent for knowledge workers to a pianist playing scales. Or Steph Curry doing drills. For you, especially given the long feedback loop, what do you do every single day to get better?

What you’re always struggling with is to understand what’s actually happening. Like, what’s actually happening on the ground.

An obvious example is if you ask an entrepreneur how the company is, they’re always going to say “great”. And that’s probably not right. You’re probably dealing with a hurricane because that’s generally the job. So, what’s actually happening inside a company? What are customers actually buying? What’s actually being adopted? What’s actually happening with the technology? What’s happening with the competition? And if you pull back to much broader issues today — what’s actually happening with coronavirus? The actual fatality rate for coronavirus is still this giant open question and there’s new research coming out every day. Despite that, a lot of people have locked into opinions that have become almost like moral positions. You want to say — “No, no, what’s *actually* happening?” We’re living a life of new science literally every day. This is what I meant earlier by being close to the ground and the previous topic of being willing to revise your views.

I am a deep believer that technology really is the driver… Technology is quite literally the lever for being able to take natural resources and able to make something better out of them.

One of the things I talk a lot about is this concept of “strong views weakly held”. I think in any business you do want to commit, you do want to act, you do want to bias towards action. Now, obviously, as you know, venture capitalists are on the opposite side of the spectrum from the hedge fund example since we have to wait like 10 years. We do end up much more committed to these things.

You have been plugged into and focused on the future for so long. Some of it is due to the nature of your role but I believe even if you didn’t have this job, you would be doing this every day. What motivates you to go read up on a new topic every day?

They’re the most interesting things in the world, right?

I am a deep believer in — after learning a lot over the years about economic history and of cultural history — that technology really is the driver. There were basically millennia of just subsistence farming industry and all of a sudden, there was this vertical takeoff a few hundred years ago. And quality of life exploded around the world. Not evenly but starting in Europe and expanding out. It’s basically all technology. It’s always the printing press, it’s the internet and on and on. And you get this incredible upward trajectory. We have the potential over the course of the next century or over the next few centuries to really dramatically advance and have life be better for virtually everybody. Technology is quite literally the lever for being able to take natural resources and able to make something better out of them.

And so it’s just it’s the most interesting and by far the most useful and the most beneficial thing I can think of doing.

On the ‘Build’ essay

Which is a good segue. I would be remiss if I didn’t ask about this. A few weeks ago you obviously had your famous essay calling on people to build. Can you walk us through the process of writing that? Was it a Jerry Maguire-style one-night memo?

Yeah, that was a single night. It was literally a single night. It started with the ponchos thing. I would describe it as a combination of “bottoms up” and “top down”. So the bottoms-up — I read the story in the Wall Street Journal about how during the height of the virus with people dying all over the place, not only did the hospitals not have enough masks for hospital workers but they also didn’t have enough medical gowns. And so the city put out a call for citizens to be able to volunteer their rain poncho so the hospital system can protect their healthcare workers. And… I couldn’t take any more. I just snapped. I literally just sat down and pounded out that essay over the next four hours, fueled by rage.

What were the most surprising responses you’ve seen?

The most surprising thing was it was a positive response for both sides of the political aisle. In particular, U.S. Representative Kevin McCarthy who is a sort of conservative and a leader in the House right now. He picked up and ran with it. He sent it to all the Republican Congress people that night and they were talking about it quite a bit. And then on the other hand, I got a very nice tweet from Saikat Chakrabarti who worked with U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

So you’ve got staunch conservatives and a staunch progressive, let’s say and both with an equally positive response. And that was representative of a broad base of responses. What was interesting was both sides of the political aisle found it equally compelling and that’s kind of what I was going for. Look, there are definitely a lot of conversations to be had about, like free market versus government versus this or that. But both sides know that something’s wrong, they can feel it.

One of the most interesting things about the essay was you actually didn’t prescribe what to build. So now that I have you, if you could pick just one thing that you wish somebody reading this would go out and think of building — what would that be?

Well, I will pick three! It’s kind of the holy trinity of our modern dilemma. It’s healthcare, it’s education, and it’s housing. It’s the big three.

So basically, what’s happened is the industries in which we build like crazy, they have crashing prices. And so we build TVs like crazy, we build cars like crazy, we make food like crazy. The price on all that stuff has really fallen dramatically over the last 20 years which is an incredibly good thing for ordinary people. Falling prices are really, really good for people because you can buy more for every dollar.

There are two ways here: you get paid more or everything you buy is cheaper. And people always really underestimate, I think, the benefits of everything getting cheaper. And so the stuff that we actually build is getting cheaper all the time. And that’s fantastic. The stuff we *don’t* build, and very specifically, we don’t have housing, we’re not building schools, and we’re not building anything close to the health care system that we should have — for those things the prices just are skyrocketing. That’s where you get this zero sum politics. I think people have a very keen level of awareness. They can’t put it into formal economic terms but they have a keen awareness of the markers of a modern western lifestyle. It’s things like — I want to be able to own a house, I want to live in a nice neighborhood, and I want to be able to send my kids to a really good school and I want to have really good healthcare.

And those are the three things where the price levels are increasingly out of reach. However we built those systems in the past, it’s failing us. And so we need to rethink. Quite literally, it’s like, okay, where are the schools? Where are the hospitals? Where are the houses?

This interview originally appeared on The Observer Effect.

screenshot images: Marc Andreessen

-

Marc Andreessen is a cofounder and general partner at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

-

Sriram Krishnan Sriram Krishnan is a former general partner at Andreessen Horowitz where he worked on international strategy based out of London, UK.

- Follow

- X