This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

Fintech’s open source evolution: how banking services will become “easy” to code

Angela StrangeUntil very recently, financial services were notoriously hard and expensive to build. Incumbents and startups alike grappled with extensive regulation, inflexible core systems, complex payment architectures, compliance hurdles, fraud, and more.

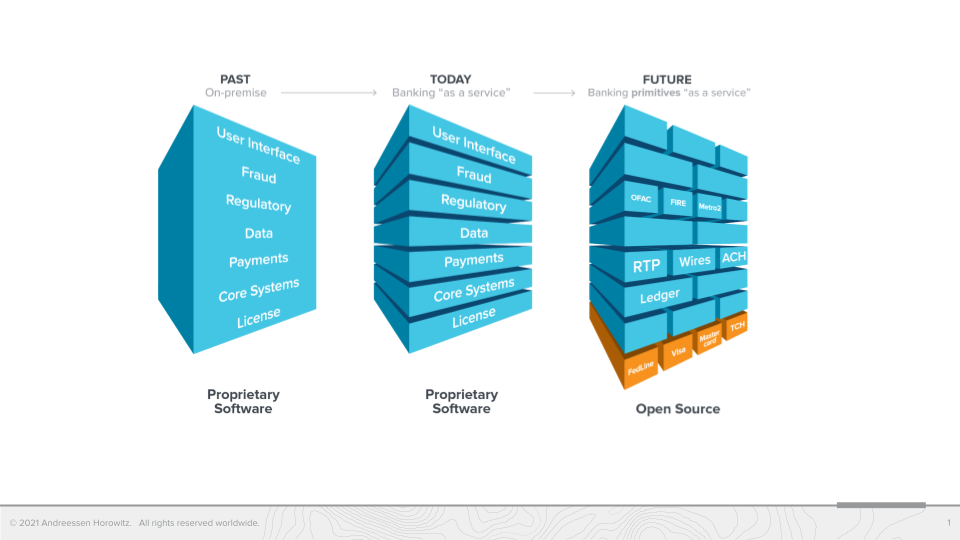

Now, the fundamental building blocks of how financial services are built are transforming — from the centuries old physical systems (marble building blocks) to code — more specifically open source primitives (software building blocks).

Like legos, these open source primitives can be assembled flexibly to allow for hundreds of different use cases — especially helpful as now any company has the capability to add fintech and as developers are seeking ways to automate our finances so software can help us make better financial decisions.

Open source allows multiple people, regardless of their geographic location, to continuously contribute to code so that it gets better and better over time and is freely available for all to use. Correspondingly, each of these Lego-like blocks are the result of ongoing collaboration between the smartest minds in the world, continuously iterating and improving upon each piece. This can dramatically improve reliability. For example, payments have thousands of edge cases, too many for even sizable teams to keep up with. Modern open source libraries are made more robust as the many contributors encounter payment edge cases and then contribute back to the code libraries with fixes and test cases.

With open source code providing the building blocks for financial services, the power, both at fintech companies and incumbents, is moving further towards the developer. Developers of any background will be able to build financial services without specialized knowledge. We will see more companies package these primitives and provide them “as a service” for more common use cases. It will be easier for companies of all types to add financial services to better serve their customers — for instance, Lyft already offers bank accounts for drivers. We will begin to see more creative use cases.

For incumbents, developers have already been the creators of such primitives, but they will now also be the buyers. With a robust ecosystem of open source libraries, product management and development teams will no longer have to seek large budget approval to buy proprietary software from the C-suite. They will be able to experiment with solutions to existing issues, as well as entirely new use cases, for free (or very low cost). This makes hiring and retaining top technical talent even more critical for existing financial services institutions as these teams will increasingly be the drivers of product innovation.

The power in financial services at companies of all sizes continues to move towards the developer.

- Read “Open Source is Finally Coming to Financial Services” »

- Watch “The Open Source Movement in Fintech” from 2021 Fintech DevCon »

- Investing in FurtherAI Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- Oil Wells vs. Pipelines: Two Strategies for Building AI Companies Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- How Big Bank Fees Could Kill Fintech Competition (July 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa, Alex Rampell, Angela Strange, and David Haber

- How Will My Agent Pay for Things? (May 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa, Angela Strange, Seema Amble, and Gabriel Vasquez

- What’s Working in AI, Rebuilding Core Banking (March 2025 Fintech Newsletter) James da Costa and Angela Strange

Getting crypto policy right

There’s a newfound recognition, both in mainstream finance and among policymakers in Washington, that crypto is here to stay. Under the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the taxation of digital assets would be used to help pay for the largest piece of public works legislation since the New Deal. The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets has been investigating the need for a new regulatory framework around stablecoins, and is expected to issue findings before end-of-year. And media reports suggest that President Biden is considering an executive order directing federal agencies to study crypto through the lens of financial regulation, economic innovation, and national security, which could set the stage for better cross-government regulatory coordination on decentralized technologies.

Missing from these conversations is an acknowledgement that crypto innovations — blockchain, cryptographic protocols, digital assets, decentralized finance and social platforms, NFTs, DAOs — represent a fundamental shift in what the internet is, how it’s structured, and who captures value.

The term “Web 2.0” was popularized in 2004, referring to the social web that defines most people’s experience with the internet today — siloed, centralized services run by corporations that capture most of the value created on these services. web3, by contrast, is decentralized in the sense that it is owned by builders, users, contributors, and communities, with the value accruing to them directly.

For financial leaders, the new forms of value and ownership created by web3 will be nothing short of revolutionary. But — like defining 20th century innovations like aviation and telecommunications — realizing the full potential of web3 will require a serious national effort to develop effective regulatory frameworks and infrastructure.

Regulation will need to be fit for purpose. web3 innovation is notoriously fast-moving and ever-changing, and decentralized technology has quickly expanded beyond its financial origins. The greater web3 ecosystem includes projects as diverse as wireless networks and digital pet universes, in addition to DeFi projects and digital assets like stablecoins that are expressly financial in nature.

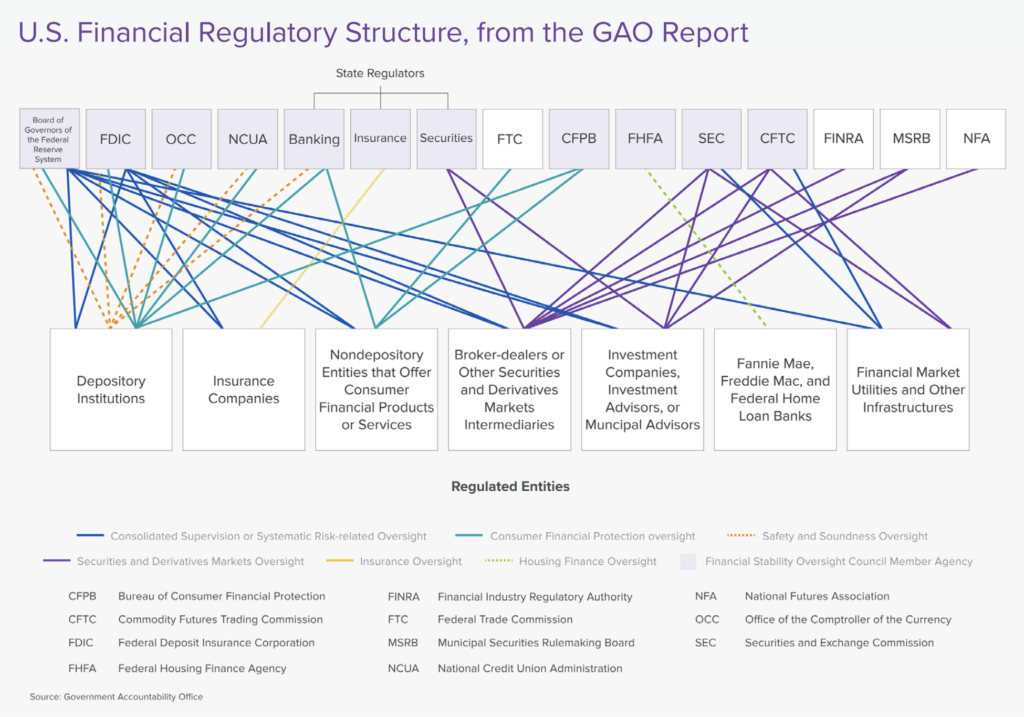

While it will need to be fit for purpose, regulation will also need to avoid fragmentation. In 2016, the Government Accountability Office found that, “Fragmentation and overlap have created inefficiencies in regulatory processes, inconsistencies in how regulators oversee similar types of institutions, and differences in the levels of protection afforded to consumers,” and recommended that Congress consider whether changes to the financial regulatory structure were needed to reduce or better manage fragmentation and overlap. Shoehorning decentralized technology into this framework is challenging for both innovators and regulators.

We at a16z have begun to articulate our vision for how to get this right. However, the task is too large for any one organization to tackle on its own. We look forward to working with builders, founders, and representatives of government and civil society on building a better internet, and with it better financial infrastructure.

Further reading on web3 and crypto policy

- How to Win the Future

- Our Proposals to the Senate Banking Committee

- A Letter to Senate Leadership

- Why web3 Matters

Automation not education

Anish AcharyaA common refrain among product managers at fintech startups is that their customers need better financial education. “If we could just teach them about the impact of collections on your credit score, the increasing returns of passive investing, or even the importance of spending less and saving more we could save them from themselves…” Or so they say! Unfortunately “they” are mostly wrong, as covered by Matt Levine this month and in a more serious take by Axios.

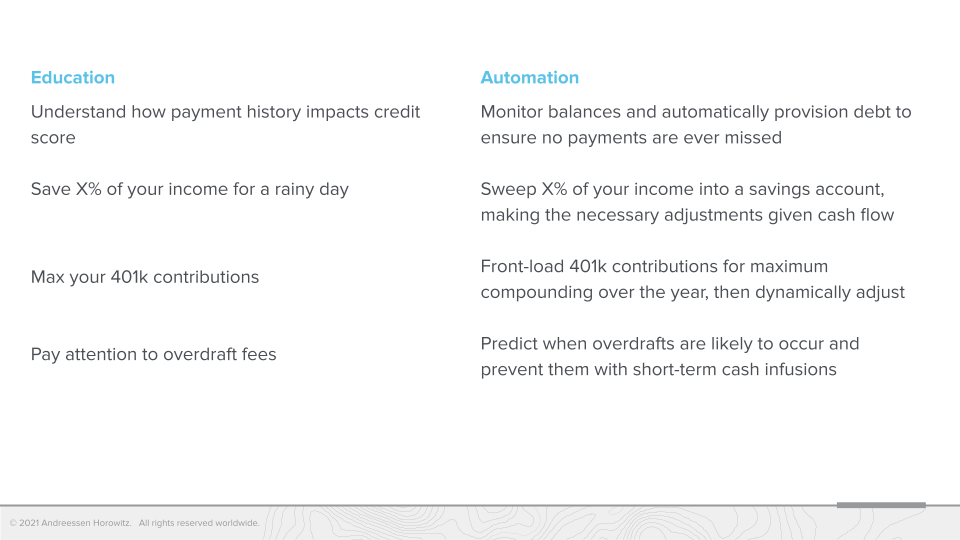

Consumers are not looking for financial education, they’re looking for better financial outcomes. And the strong form of this will be delivered via software automation, not education. Here are a couple of simple examples inspired by the famous “index card” approach to education:

It’s really hard to change people’s behavior towards their money. As consumer fintechs expand to serve an increasingly large share of the US consumer banking market, they will drive the best outcomes by building the wisdom of financial education into product automation.

Financing the hustler economy

Sumeet SinghThe next-generation of business owners are internet-native hustlers — they know how to make money on the internet, have multiple streams of income, and work with talent and partners across the globe. These hustlers have been enabled to run internet native businesses by platforms — Shopify for dropshippers (Shopify had more traffic than Amazon for the first time ever), StockX for sneaker resellers (which saw $1.8B in transaction volume in 2020), TikTok for up and coming musicians, Fiverr and Upwork for designers, and Discord for community builders.

While these hustlers can now easily spin up businesses with these platforms, they have specific financial needs that traditional financial institutions aren’t able to support. Fintech companies like Current and Chime have solved some of the personal financial needs of these hustlers, but they also need financial products (banking, lending, payments) tailor-made to their business needs.

In many cases, these products may look completely different than what we expect a financial product to look like. For instance, they may recently allow businesses to accept payments over messaging platforms, get virtual cards attached to lines of credit to buy sneaker drops, or access instant payments for TikTok and YouTube streams. The companies that make these products will also likely embed themselves in, or even create, communities, building both trust with their hustler customers and their own proprietary distribution channels.

As the line between consumers and businesses continues to blur, we could see a world in which these business-first financial products penetrate the consumer-side of these hustlers’ lives, causing more vertical-specific and fragmented consumer neobanks to emerge.

- B2FI: Demystifying Software Sales Into Financial Institutions David Haber, Sumeet Singh, Brad Kern, and Katy Nelson

- More Countries, More Problems: Selling AI Products Around the World is Still Too Hard Sumeet Singh and Angela Strange

- Generative AI is Coming for Insurance (May 2023 Fintech Newsletter) Joe Schmidt, Sumeet Singh, and Seema Amble

- Beyond Payments for High-Risk Industries Sumeet Singh and Seema Amble

- Financial Services Will Embrace Generative AI Faster Than You Think Angela Strange, Anish Acharya, Sumeet Singh, Alex Rampell, Marc Andrusko, Joe Schmidt, David Haber, and Seema Amble