One of the holy grails in the newco world is to build out a digital platform that successfully serves the needs of a broad number of adjacent verticals, and become the definitive platform in its space. We know the now-canonical early examples of this: Amazon, eBay, Craigslist. And we also know that once that holy grail of a new digital platform is attained, competitors quickly come a’ callin’.

One of the most effective forms of that competition often comes in the form of newcos who aspire to take chunks out of that emergent platform by better addressing the needs of a specific vertical within that platform—by creating a user experience or business model that’s much more tailored to the unique attributes of that vertical. StubHub, for example, took a big chunk out of eBay by creating a ticket-buying experience that was so in tune with the needs of those specific buyers and sellers—with ticket verification, venue maps, and rapid shipping—that they were able to get strong traction in spite of the fact that their fees were substantially higher than what eBay was charging (which likely motivated eBay to buy Stubhub in 2007).

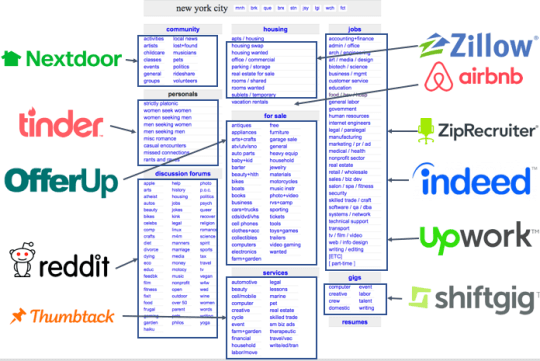

The classic example of this dynamic in action is well captured in this graphic of the unbundling of Craigslist:

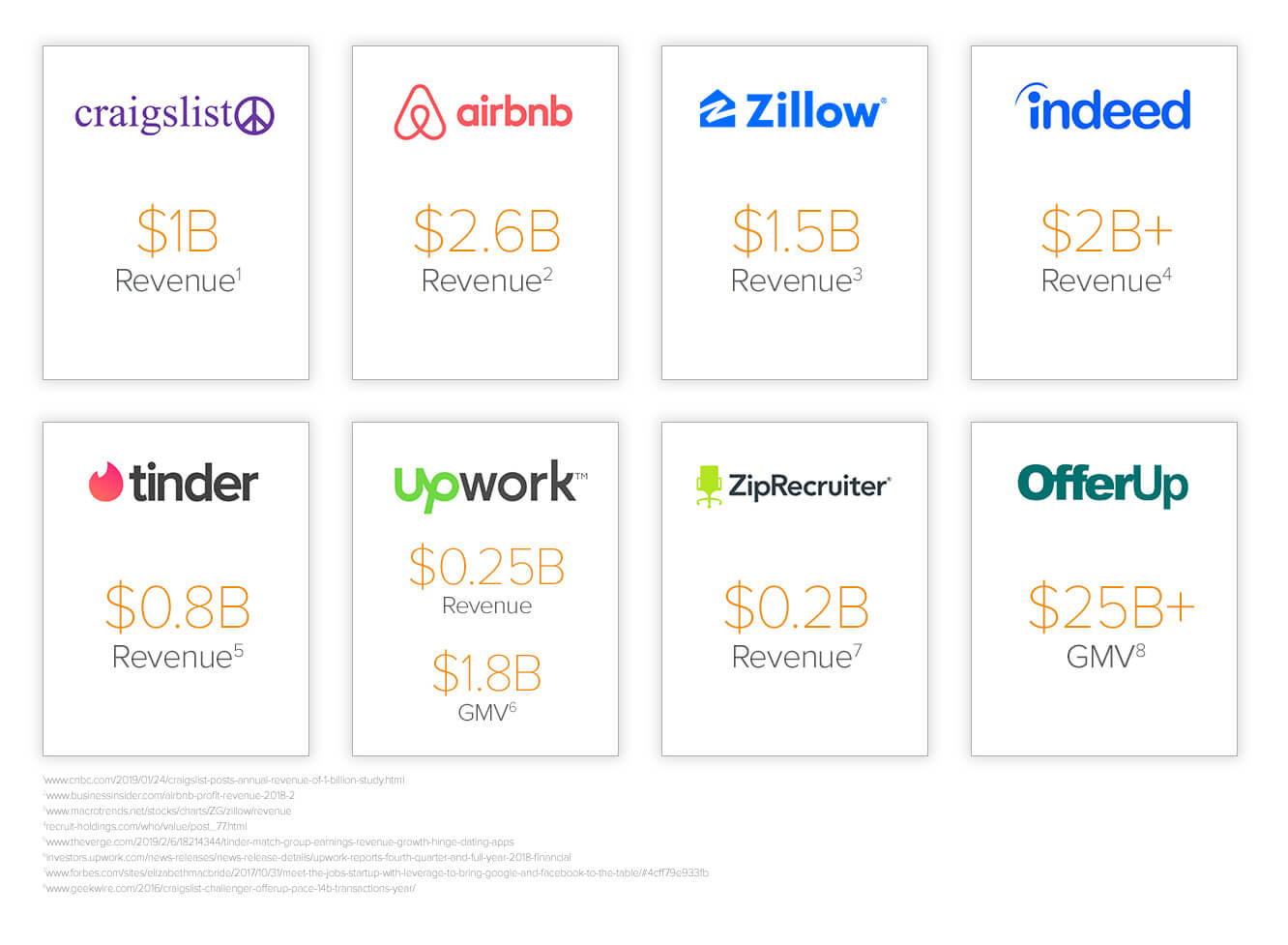

We’ve seen this dynamic play out several times now (and Craigslist, Amazon and eBay still remain prime targets, given their large GMVs and attractive vertical markets). In fact, this strategy can sometimes be so powerful that some of these new businesses are not only bigger than the original vertical they disrupted, but bigger than the platform as a whole. In other words, they serve the needs of users in their vertical so much better that they can compete for a much larger share of their vertical against both analog and digital players.

The moral of the story is this: In all but a few circumstances, the broad horizontal verticals eventually break. They become a victim of their own success. As the platforms grow, their submarkets grow too; their product gets pulled in a million different directions. Users get annoyed with an experience and business that caters to the lowest common denominator. And suddenly, what was previously too small a market to care about is a very interesting place for a standalone newco. Like clockwork, a new wave of innovation begins to swell, picking off the compelling verticals the new horizontal players cannot satisfy.

If you know which platforms are teetering on this precipice, you’ll know where to look for both opportunity and innovation.

“If you know which platforms are teetering on this precipice, you’ll know where to look for both opportunity and innovation.”

YouTube, for example—a monster platform in video, with approximately 1.3 billion active users who currently generate $4 billion in annual revenue—is currently experiencing this. A large number of newcos are trying to get a piece of that action, by targeting specific categories and audiences within the larger general platform. Twitch has seen a lot of success in gaming videos (Amazon acquired the company for just under $1 billion in 2014); TikTok has exploded in short-form mobile videos; MasterClass by targeting educational videos; Overtime by zeroing in on sports, with highlights and original content aimed at Gen Z; and many startups are looking now to claim the space of video content for kids (which YouTube is undesigned for—so much so that it was recently fined).

Zillow is also being targeted for unbundling. The leading digital real estate platform in the U.S., Zillow aspires to serve needs across many sub-verticals in real estate, from buying/selling a home, to leasing or renting a home/apartment, to sourcing home loans, to finding an agent. It’s current market cap is $7 billion. But those are a lot of different marks, with different business models and different users—and Zillow has only just scratched the surface of the category’s migration from analog to digital. As a result, there are multiple newco digital competitors targeting chunks of the market. For example, Compass, OpenDoor, and FlyHomes are targeting the buying/selling a home vertical, but in unique ways that are difficult for Zillow to imitate.

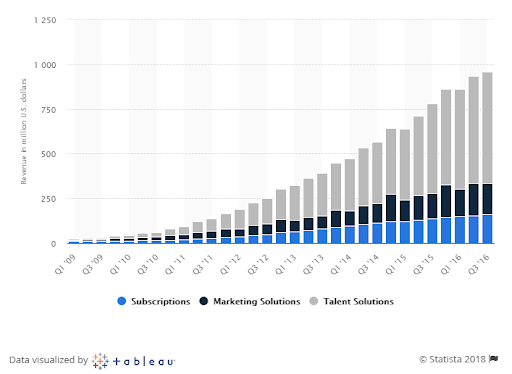

One of the most attractive “platform” targets we see today, only just starting to be chipped away at, is LinkedIn. Take a look at LinkedIn’s revenue from 2009-2016. At the time of LinkedIn’s June 2016 sale to Microsoft for $26.2 billion, their quarterly revenue of the time of sale was ~$1B.

Like all these other horizontal players, LinkedIn offers essentially the same user experience across job verticals. For jobs like white collar roles, the site works well. But for other, more specialized verticals—blue collar jobs, engineers, or health care workers, for example—their needs are met much less well. Add to that the perception that the company might not continue to be as innovative or risk-taking as a subsidiary of one of the biggest companies in the world, and you’ve got very ripe opportunities for disruption by innovators with tailored vertical approaches.

We are already beginning to see innovation bubbling up with newcos using this vertical play in the jobs platform space. From engineering (Hired) to blue collar (Merlin, Wonolo) to oil services (RigUp) to hospitality (Pared, Instawork, Qwick) to bookkeeping (Paro), each of these new companies are building a user experience and business model that works better—for both candidates and employers—than the generic LinkedIn model. In other words, the great unbundling of LinkedIn may have already begun.

Savvy founders know that finding the right market at the right time can be like a cheat code for startup success. Looking at verticals within the broad horizontal platforms that are near their breaking point is like a cheat code for a cheat code: if you’re paying attention, it will point you to the next great unbundling and where the next wave of opportunity and innovation will come from.

-

Jeff Jordan is an a16z General Partner focused on consumer companies.

-

D'Arcy Coolican D'Arcy Coolican is a partner on the investment team where he focuses on marketplaces, social networks, and consumer technology companies.