A strong multiproduct strategy is a cornerstone of a credible growth story for any scaling B2B company. Depending on your goals, new products can deepen the wallet share of your existing customers by focusing on new users or new use cases, or they can expand your TAM by targeting new customers, new geographies, or new verticals. In each case, successfully launching these products means finding product-market fit all over again—but this time, you have a much slimmer margin for error.

This is why considering pricing and packaging ahead of time not only becomes a competitive advantage, but a necessity.

Nailing pricing and packaging early can help you gauge whether investing in a given product idea is even worthwhile. (After all, if customers aren’t willing to pay enough for you to generate a return from a product, there’s no reason to build it.) And if it is worthwhile, effective pricing and packaging can help you capture the value of that product much more efficiently—which means you can show an ROI on your investments.

The fundamental pricing processes still apply when you’re launching a new product. You’ve found product-market fit before, so we’re not going to rehash those processes for you. You identify a strategically wise problem to solve, build a solution, and conduct market research—then you align on your pricing metric, segmentation, and willingness to pay. Instead, we’ll explore what’s different about these last three when you price and package a second (third, or fourth) product, so you can avoid common pitfalls and set up your product launch for success.

Pricing metric

Revisiting your pricing metric generally comes first when you’re pricing a new product, since you might be delivering a different kind of value to a different customer. The metric you use to price your first product isn’t necessarily the one you use to price your next.

This can get trickier when you’re expanding your footprint and serving different customers. Your existing customers will be used to paying for your product in a particular way (such as subscriptions), but if you’re moving into a market where customers pay for products in a different way (like usage), you’ll likely need to figure out a new pricing metric for your new product.

Let’s make this more concrete.

Consider when Atlassian launched JIRA Service Desk. Atlassian’s flagship product, JIRA software, was intended for developers to create, track, and resolve bugs while providing visibility to the entire team. It was, at its heart, a collaboration tool that monetized per user. Eventually, Atlassian noticed that IT, legal, and customer support teams started to use JIRA software to track their own workflows, and so created JIRA Service Desk—a product more akin to a “help desk”—to serve these new customers. To more effectively monetize this new customer segment, Atlassian created a new pricing metric: per agent. “Agents” referred to members of IT, legal, or customer support teams who had permission to create, update, and close tickets. This allowed any member of a customer’s org to create a ticket, and they would only have to pay for the legal, IT, or customer support team members who actually addressed those tickets.

As we referenced earlier, we’re also starting to see more companies navigate this question as they adopt usage-based pricing, particularly with generative AI. Your company might monetize your first product through subscriptions, but your second product might mark a move into a market where customers generally prefer to be billed by usage. Because you’ve only monetized through subscription, you don’t have the tech stack or GTM structure to effectively implement UBP. Do you make massive changes to your GTM org and tech stack, or do you continue to bill by subscription in order to increase traction with your existing customers?

Segmentation

For most growth-stage companies, launching an additional product expands your TAM either by solving a similar problem for different personas or by solving a new problem for your existing personas. Segmenting your current and potential customers first helps you understand what you should build. Then, you can figure out how to package up our product suite to deliver the right value to the right customer—and capture the incremental value of that new market.

Many successful product launches into adjacent markets respond to “pulls” from existing customers. Think: “we love your CRM, but when will you guys offer a marketing automation product so we can streamline our go-to-market operations?” Talking to your existing champions can give you a great signal into the capabilities your customers are itching to add, and they can also offer you warm introductions to business leaders in other parts of the org who would be responsible for buying your new product.

We’ve also seen successful additional product launches stem from serving unexpected users using your product in unexpected ways. This is partially why Atlassian built out the JIRA Service Desk we mentioned in the previous section: they found that IT, legal, and customer support users—not their intended buyer persona, developers—were using JIRA software to track their own workflows. By building out a separate product to directly address the needs of those legal, IT, and customer support users, Atlassian could capture more value from that new market.

Getting crisp on your segmentation is also a great way to avoid one of the most common pitfalls we see when companies expand their footprints in an org: cannibalization. Creating packages that deliver the right value to the right customer disincentivizes personas with bigger budgets from purchasing packages intended for those with smaller budgets. To extend the JIRA example, Atlassian built out a new, streamlined UI for JIRA Service Desk that made it quick and easy for anyone to create tickets, then gave agents the tools they needed to address and solve those tickets. To make sure they were delivering the right value to the right customer, Atlassian charged more per JIRA Service Desk agent than per JIRA software user.

Willingness to pay

Deriving willingness to pay helps you understand not only the demand for your product, but also how quickly you can expect to see a return on your investment in the product. Like we mentioned earlier, there’s no point in building something if your customers aren’t willing to pay you enough to make your investment in that product worthwhile.

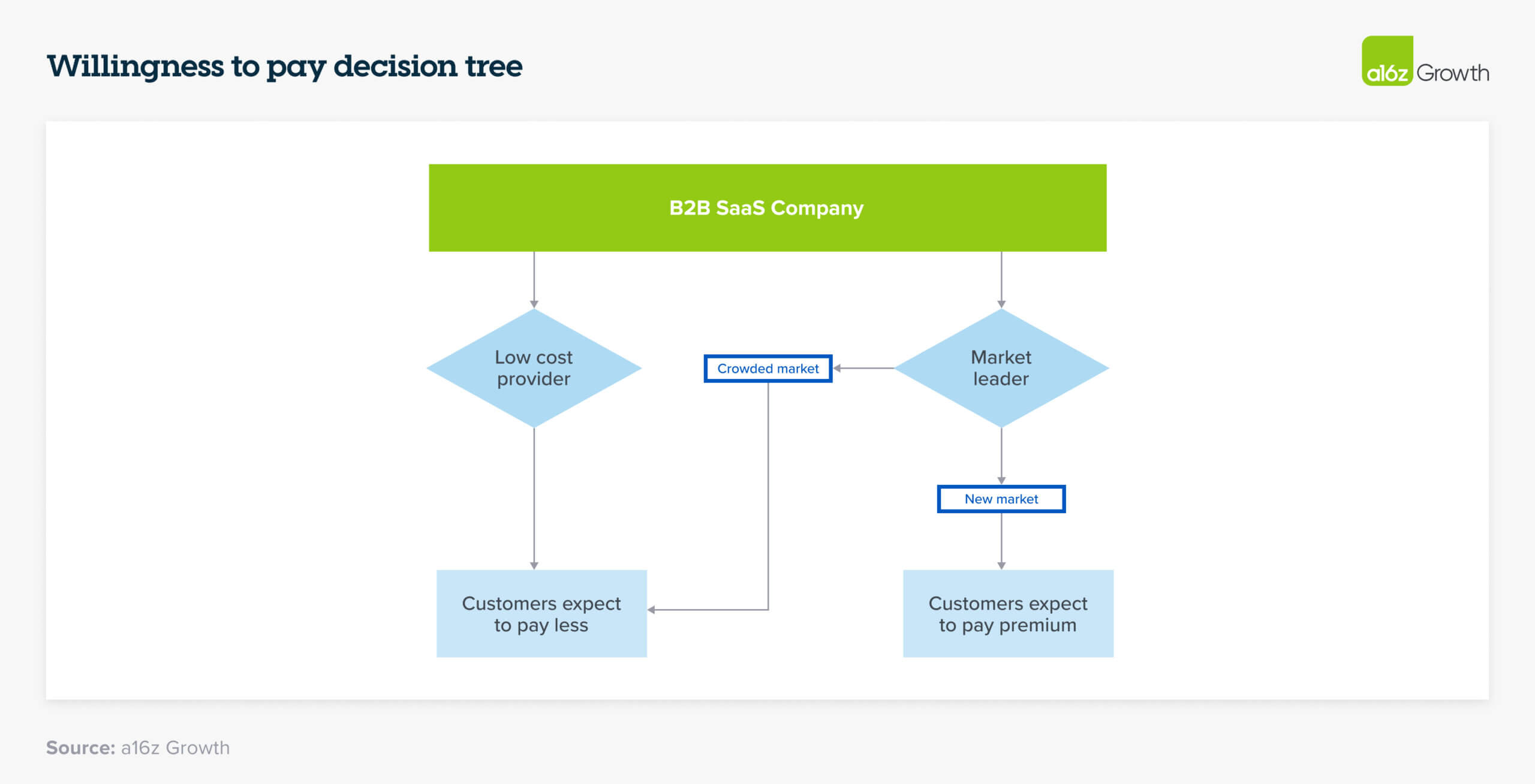

We follow a decision tree when counseling portfolio companies on ascertaining new customers’ willingness to pay. If you’re a low-cost provider, customers will likely see your low price point as part of your value proposition and will likely want to pay less for your new product than they would for an alternative. But if your first product is now a market leader and you charge a premium for it, that doesn’t necessarily mean that your customers will be willing to pay a premium for your second product. Instead, it’s helpful to assess if you’re creating a new category (for which there won’t be any established budget) or if you’re competing in a crowded market where you’d need to price lower in order to shave off market share from incumbents.

In the last case, market analysis can help you figure out how low you’d need to price to capture market share. When you’re creating a new category, however, the standard willingness-to-pay analyses are still helpful. As a rule of thumb, customer interviews work well with fewer than 10 customers, van Westendorp analysis works well for about 50 customers, and conjoint analyses work well for over 100 customers. (Some of these approaches can miss the “total wallet share” question, so it’s wise to include both the individual feature and full platform willingness to pay in the survey work.) As we’ve mentioned in a previous podcast, it can also be helpful for your sales and marketing team to put themselves in the shoes of your buyer to understand their “as-is” environment: what pain points do they have? How urgently do they need to be solved? This feedback can help you triangulate your new customers’ willingness to pay.

Though these analyses are standard fare for pricing exercises, it’s still important to take time to do them, and do them early. In a rush to get a new product out the door and generate revenue, we’ve seen founders and their teams forgo this exercise, or do it too late, and have it come back to bite them later when they can’t secure enough budget from their customers.

Launching your second act or building out your suite of products is essential to building a credible growth story for the long haul. Understanding how pricing fundamentals shift when you’re launching additional products can not only help you find product-market fit more quickly—it can also help you capture the value those products create and continue scaling.

Many thanks to Michael King for his contributions to this post.

- How 100 Enterprise CIOs Are Building and Buying Gen AI in 2025

- When and How Should You Bundle Your Products? Our Gut-Checks

- The Three Most Common Challenges with Freemium—And How to Fix Them

- Pricing and Packaging Your B2B or Prosumer Generative AI Feature

- Customers Want Predictability in Usage-based Pricing. Here’s How to Help Them Get It.