The internet is a miracle of universal access to opportunity, inquiry and connection. And ads pay for that miracle. As Marc has long argued, “if you take a principle stand against ads, you’re also taking a stand against broad access.” Ads are why we have nice things.

So, the announcement last month that OpenAI plans to launch ads for free users is probably the biggest piece of news-that-isn’t-actually-news of 2026 (so far). Because of course, if you’ve been paying attention, the signs that this would happen have been everywhere. Fidji Simo joined OpenAI in 2025 as CEO of Applications, which many people interpreted to mean “implement ads, just like she did at Facebook and Instacart.” Sam Altman had been teasing the rollout of ads on business podcasts. And tech analysts like Ben Thompson have been predicting ads pretty much since ChatGPT launched.

But the main reason that ads aren’t a surprise is because they’re the best way to bring a service on the internet to the largest possible number of consumers.

The long tail of LLM users

“Luxury beliefs”, a term that came into vogue a few years ago, are stances taken not really for principled reasons, but for optical reasons. Tech has plenty of these, especially when it comes to advertising. For all the moralistic hand-wringing over “Selling data!” or “Tracking!” or “Attention harvesting” and other bingo words, the internet has always run on ads and most people like it that way. Internet advertising has created one of the greatest “public goods” in history, for the negligible price of occasionally having to look at ads for cat snuggies or hydroponic living room gardens. People who pretend this is a bad thing usually are trying to prove something to you.

Any internet history buff knows that ads are a core part of how platforms eventually monetize: Google, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok all started free, and then figured out monetization with targeted ads. Ads can also be a way to supplement the ARPU of a lower-value subscriber, as in the case of Netflix’s newer $8/month option, which introduced ads to the platform. Ads have done a very good job of training people to expect most things on the internet to be free or extremely low-cost.

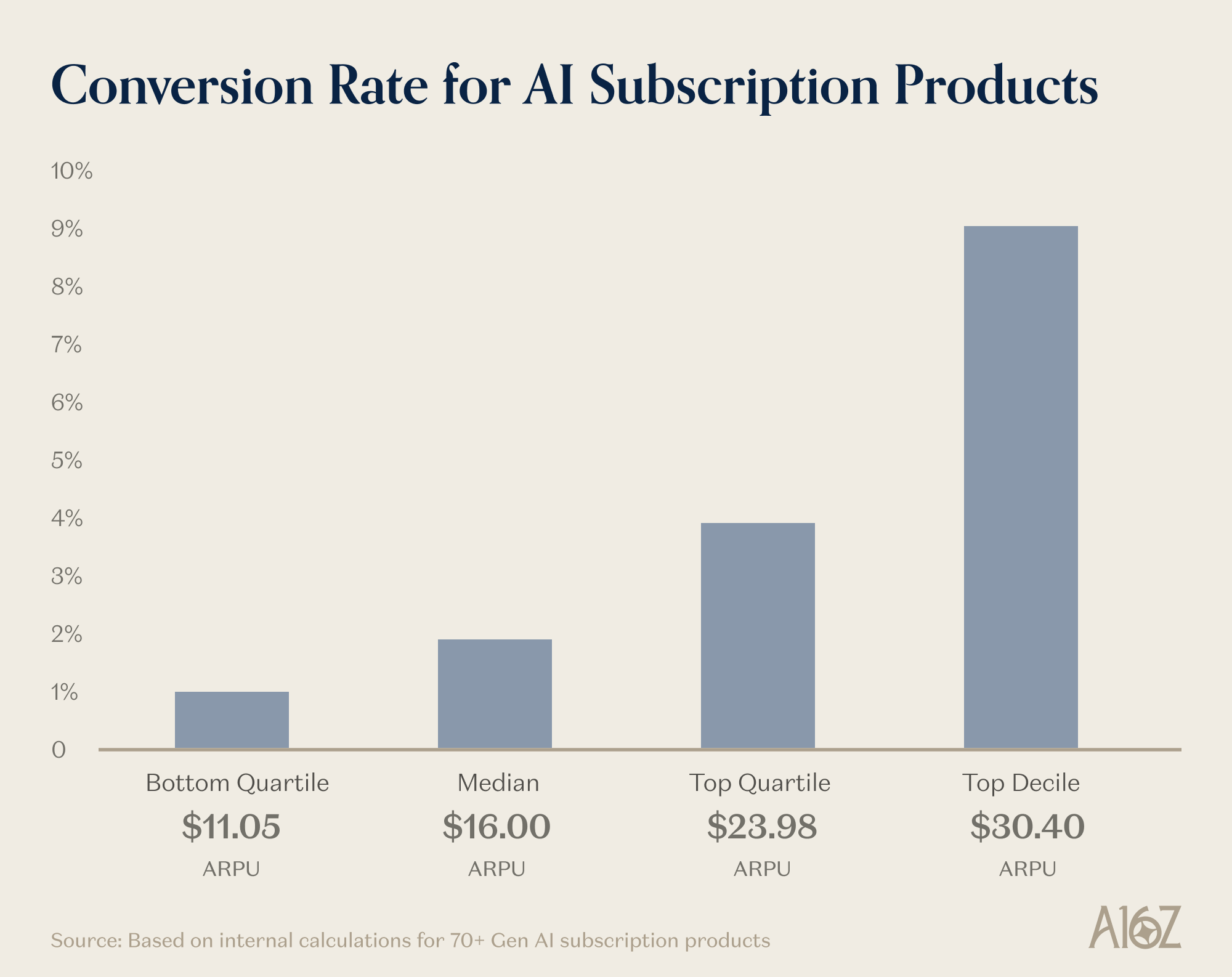

This pattern can now be seen across frontier labs, as well as specialized model companies, and smaller consumer AI companies. From our survey of consumer AI subscription companies, we can see that converting subscription users can be a real challenge for all of them:

So what’s the solution? As we all know from past consumer success stories, ads are often the best way to scale your service to billions of users.

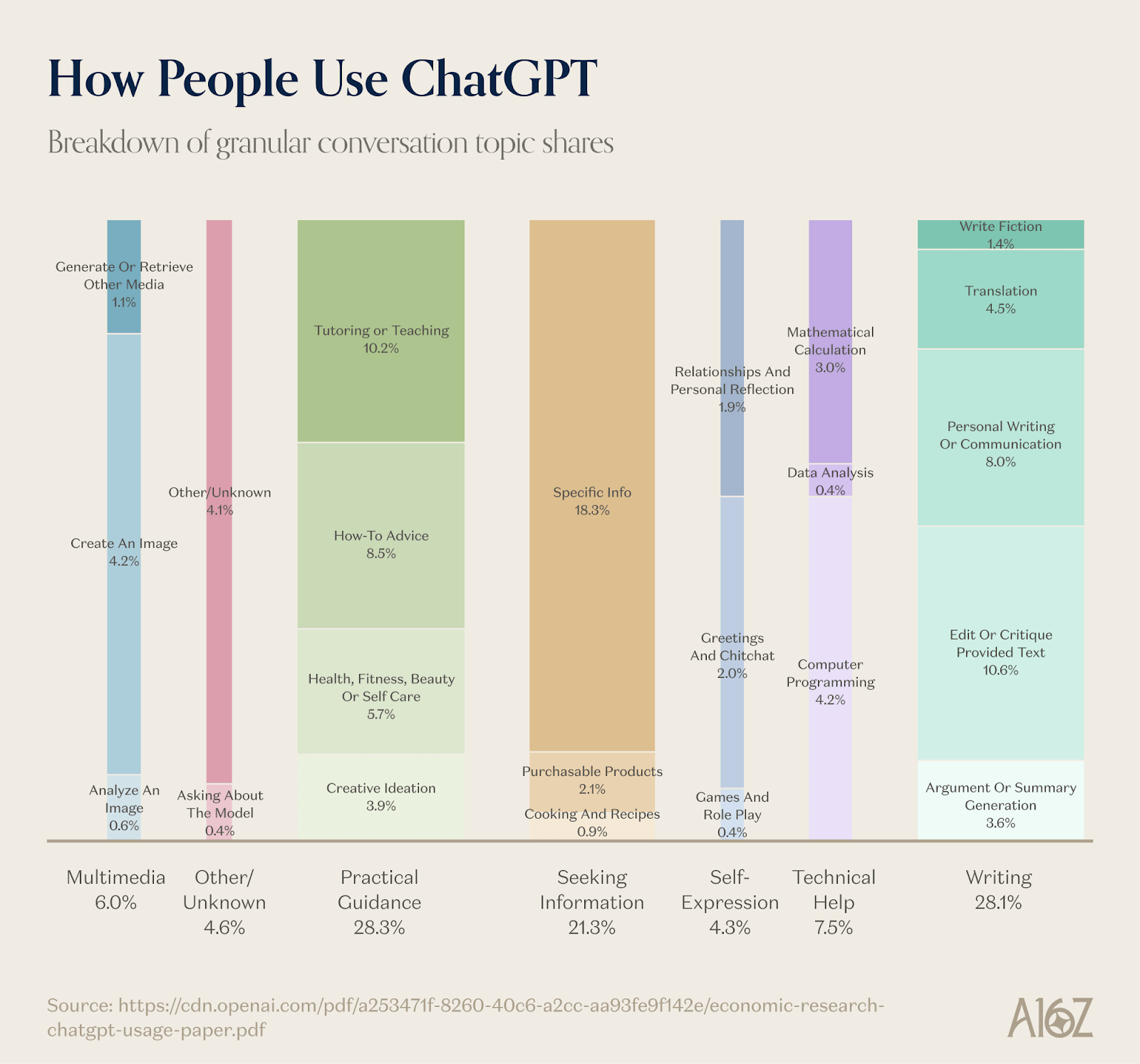

To understand why most people don’t pay for AI subscriptions, it helps to understand what people use AI for. Last year, OpenAI published data on exactly this.

In short, most people use AI for personal productivity: things like writing emails, searching for information, and tutoring or advice. Meanwhile, higher value pursuits, like programming, make up a very small percentage of overall queries. Anecdotally, we know that programmers are some of the most committed users of LLMs, with some even calibrating their sleep schedules to optimize for daily usage limits. For these users, a $20 or $200/month subscription doesn’t feel exorbitant, because the value that they’re getting (the equivalent of a swarm of highly productive SWE interns) is likely orders of magnitudes greater.

But for the users who are using LLMs for general queries, advice, or even writing help, the onus of actually paying is too great. Why would they pay for an answer to questions like “why is the sky blue” or “What are the causes for the Peloponnesian War” when previously a Google search would direct you to a good-enough answer for free. Even in the case of writing help (which some people are using for email jobs and rote work), it often doesn’t do enough of a person’s job to justify an individual paying for a subscription. Additionally, advanced models and features often aren’t needed by the majority of people: you don’t need the best reasoning model to write emails or suggest recipes.

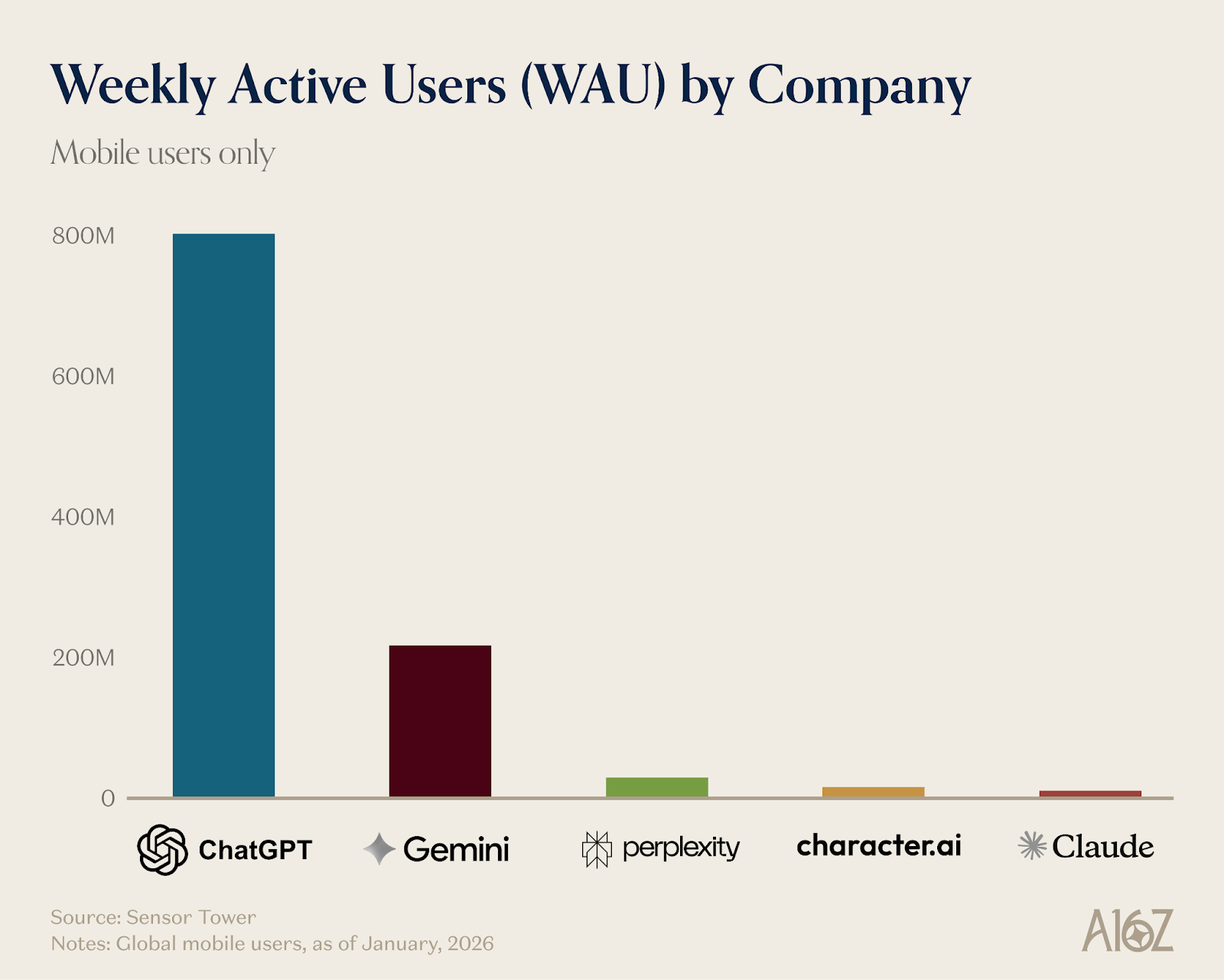

Let’s take a step back and acknowledge something for a moment. The absolute number of people paying for a product like ChatGPT is still enormous: 5-10% of 800M WAUs. 5-10% of 800M is 40-80M people! On top of that, the price point for Pro at $200 is ten times what we thought the ceiling was for consumer software subscriptions. But, if you want to get ChatGPT to a billion people (and beyond) for free you need to introduce a product other than subscriptions.

The good news is that people actually do like ads! Ask the average Instagram user, and they’ll probably tell you that the ads they get are ridiculously useful: they get served products they actually want and need, and make purchases that actually make their lives better. Framing ads as exploitative or intrusive is regressive: maybe we feel that way about TV ads, but targeted ads are actually pretty great content most of the time.

I’m using OpenAI as an example here (since they have been one of the most forthcoming labs when it comes to comprehensive disclosures around usage trends). But this logic applies to all frontier labs: they will all need to introduce some form of advertising eventually if they want to scale to billions of users. The consumer monetization model is still unsolved in AI. In the next section, I’ll walk through some approaches.

Possible AI Monetization Models

My general rule of thumb in consumer app development is that you need a minimum of 10M WAUs before introducing ads. Many AI labs are already at this threshold.

We already know ad units are coming to ChatGPT. What might they look like, and what other ad and monetization models are viable for LLMs?

- Higher value search and intent-based advertising: OpenAI has confirmed that these kinds of advertisements (ingredients for recipes, hotel recommendations for trips, etc.) are coming to the platform for free and low cost-tier users. These ads will stand apart from answers in ChatGPT, and will be clearly labeled as sponsored. Over time, the ads may feel more like prompting: you’ll prompt an intent to purchase something, and the agent will fulfill your request end-to-end, from a list of sponsored and unsponsored content.

In a lot of ways, these ads are reminiscent of the earliest ad units in the 90’s and 2000’s, and what Google has perfected with their sponsored SEO ad units (for what it’s worth, Google still derives the vast majority of revenue from its ad business, and only ventured into subscriptions 15+ years into their history).

- Context-based ads in the style of Instagram: Ben Thompson has made the point that OpenAI should’ve introduced ads much earlier to ChatGPT responses. First, it would have acclimated non-paying users to ads much earlier (back when they had a true head start on Gemini’s capabilities). Second, it would have given them a lead on building a truly great ad product, which anticipates what you want rather than opportunistically feeding ads based on intent-based queries.

Instagram and TikTok can deliver an amazing ad experience that shows you products you never knew you wanted, but absolutely need to buy immediately and many people find the ads to be useful rather than obtrusive. Given the amount of personal information and memory OpenAI has, there is plenty of opportunity to build a similar ad product for ChatGPT. Of course, there are differences between the experience of using these apps: can you transpose a more “lean-back” ad experience on Instagram or TikTok into the more engagement-heavy model of using ChatGPT? It’s a much harder problem, and a way more lucrative one to get right.

- Affiliate commerce: Last year, OpenAI announced an instant checkout function in collaboration with marketplace platforms and individual retailers, that would allow users to make purchases from directly within their chat. You can imagine this being built out into its own dedicated shopping vertical, in which an agent proactively sources clothing, home goods, or rare items you’re tracking because of their limited availability, and the model provider getting a cut of revenue from the marketplaces featured in this service.

- Games: Games are often forgotten or glossed over as being their own kind of ad unit, and we don’t know for sure how they play into ChatGPT’s ad strategy, but they’re worth mentioning here. App install ads (many of whom were for mobile games) were a huge percentage of Facebook’s ad growth for years on end, and games are so inherently profitable that it’s not hard to imagine big ad budgets getting spun up here.

- Goal-based bidding: This is a bit of a fun one, for the fans of auction algorithms (or for former blockchain gas-fee optimizers who want to pivot into LLMs). What if you could set a bounty for a specific query (e.g., $10 for Noe Valley real estate alerts) and have a model throw an outsize amount of compute at a particular outcome? You’d get perfect price discrimination based on the determined “value” of a question, and could also get better guaranteed chain-of-thought reasoning for searches that are particularly important to you. Poke is one of the best examples of something like this: people had to explicitly negotiate with the chatbot for subscription to the service (of course this didn’t map to compute costs, but it’s still a fun illustration of what it could look like).

In some ways, this is already how some models function: both Cursor and ChatGPT have routers that select models for you, based on the interpreted complexity of the query. But even if you’re the one selecting models from a dropdown, you don’t get to choose the underlying amount of compute a model throws at a problem. For highly motivated users, being able to specify an example of how much a problem is worth to them in dollar amounts could be appealing.

- Subscriptions for AI entertainment and companions: There are two main use-cases that users of AI have demonstrated a willingness to pay for: coding and companionship. CharacterAI has one of the highest WAU counts of any non-lab AI company. They can also get away with charging a $9.99 subscription fee for their service because what they offer is a hybrid of companionship and entertainment. But even though people do pay for companion apps, we have yet to see companion products cross the threshold where they can reliably monetize via ads.

- Pricing by token usage: In the AI creative tooling and coding space, pricing by token usage is also a common monetization model. This has become an attractive pricing mechanism for companies with power users, which allows them to differentiate and charge more in accordance with usage.

Monetization is still an unsolved problem in AI, with the majority of users still enjoying the free tier of their preferred LLM. But this will only be temporary: the history of the internet has taught us that ads find a way.

If you’re working on building the next generative AI-native ad stack, or if you’re scaling your way to tens of millions DAUs, reach out at bryan@a16z.com or @kirbyman01 on X.