Any time an executive takes a new job, it’s a big change—for the company and for the executive. For a CEO, executive hires are among the highest-stakes hires you will make, with implications for your organizational design, leadership team dynamics, and the future growth of the company. For the new executive, it’s a huge decision to leave a role where they’ve established themselves as a leader with influence and credibility for a new organization where they’ll need to get up to speed on a new company and its culture, establish relationships and credibility, build out teams, set up new processes, and more.

With such high stakes, it’s not surprising that, in our experience, the average executive search takes 130 days, and it’s not uncommon for some searches to take 6 months or longer. If they’re open to new opportunities, the most in-demand executives are likely interviewing with multiple companies at once.

Yet as important, competitive, and time-consuming as executive hiring is, many companies don’t have a formal hiring process. A well-designed and executed hiring process, driven by an engaged CEO, will give you an edge in recruiting and retaining top talent, shorten the time it takes to hire and onboard an executive, and set a new leader up for wins within the first 100 days—which is, in our experience, the leading indicator that an executive will work out long term.

Of course, no methodology guarantees a good hire every time, so free yourself of the idea that you’re going to always get it right. If you hire 10 leaders, not all 10 are going to work out—but an effective hiring process and a determined CEO will increase your batting average.

In this post, we go step-by-step through the hiring process we use at a16z, based on thousands of executive searches with hundreds of companies.

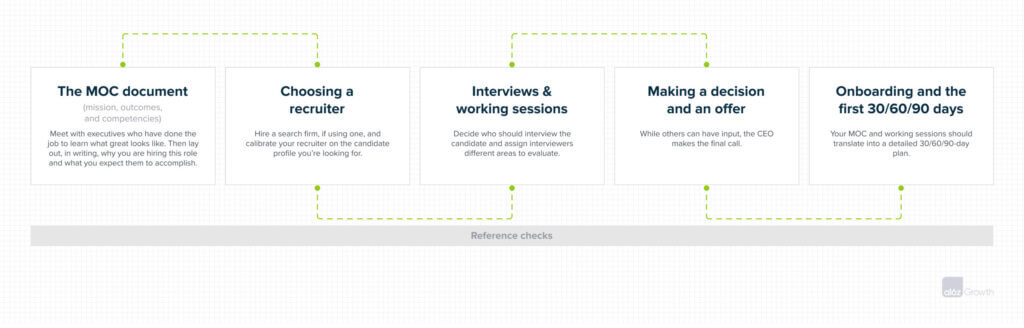

The Hiring Process

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The MOC (missions, outcomes, and competencies) document

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A high-quality process is useless without a strong leader to drive it. The companies that are most successful at executive hiring have a CEO with a strong recruiting mindset. These CEOs know: if you can’t define it, you shouldn’t hire for it. They understand that most searches fail before they even start because there isn’t a clear answer to the question, “Why are we hiring for this role?” They also realize that this can be a deceptively difficult question to answer because they’re in the tough position of hiring someone to do a job they’ve never done.

At the start of an executive search, we usually tell CEOs to talk to people who have been in that role at companies they admire. Spending an hour with someone who is a great CRO, VP of sales, or CHRO will help clarify what exactly the role is, what great looks like, and what an incoming leader will need from you to be successful. These executives are also likely well networked, which can also help with sourcing quality candidates. On occasion, we’ve even seen executives become interested in a role after talking to a CEO. But the primary goal of the conversation should be tapping this experienced executive’s expertise to get crystal clear on why you want to hire someone in that particular role. What do you hope a particular executive will fix? What outcomes do you want them to drive? What can (and can’t) you expect them to deliver? What do they likely need to be successful?

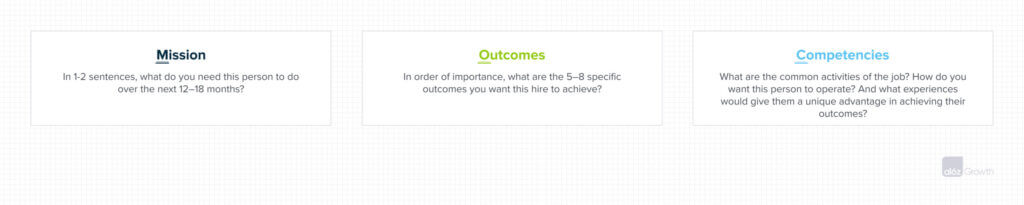

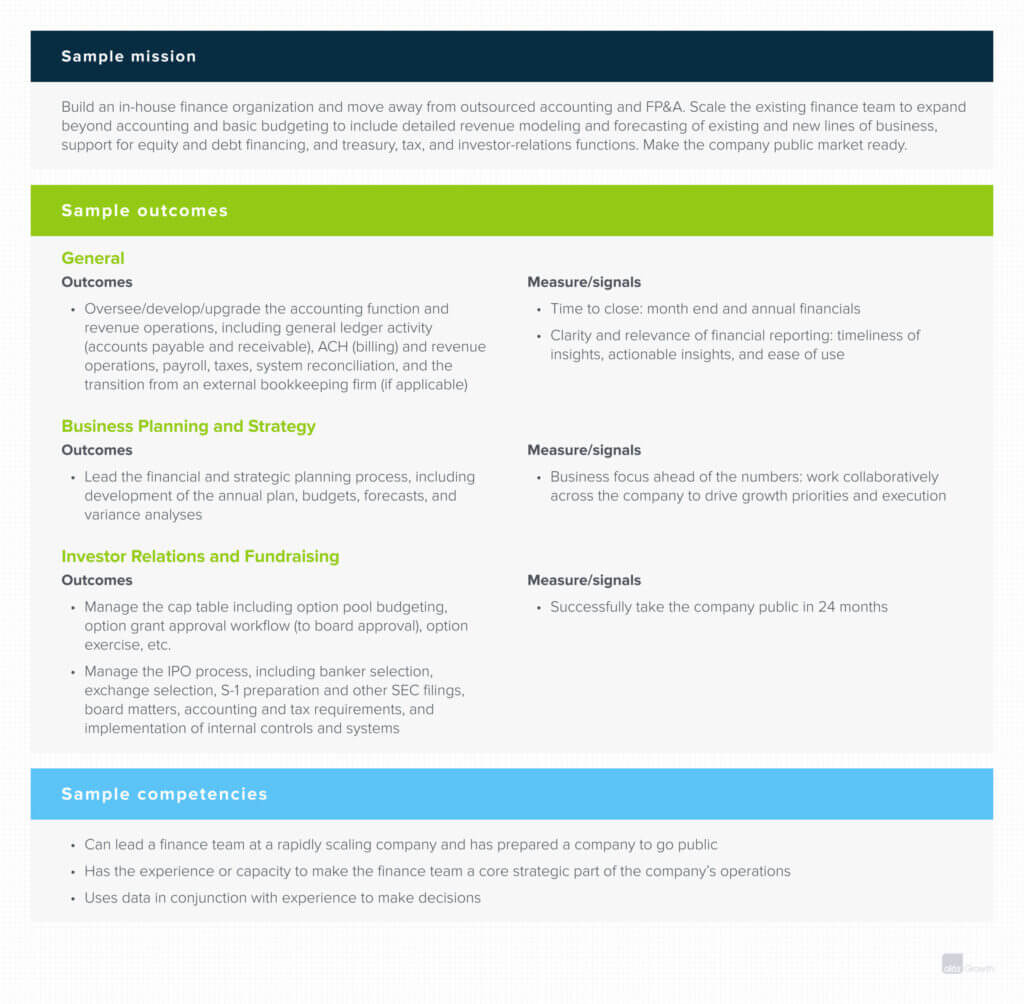

Once a CEO is clear on why they are hiring a particular role, we have them write a MOC—a document that outlines the mission, outcomes, and competencies of the job, helping to articulate the business case for hiring an executive and what, specifically, the new hire will be expected to accomplish over the next 12–18 months. In short, it lays out the stuff you need that executive to get done.

While it outlines the role, the MOC is not the same as a job description. Whereas the job description is posted externally for potential candidates, the MOC is an internal, more detailed source of truth that links the role’s intended outcomes (the actual work to be done) to explicit numbers and specific projects to align everyone at the company—and the eventual new hire—on what the executive will do.

In the course of drafting the MOC, you’ll want to decide who is included in the interview team. These should be people who you trust to evaluate candidates and who will be critical to the hire’s day-to-day success. You’ll want to get their input on why you’re hiring for this role and what success looks like. Keep in mind, it’s unlikely you’ll have complete agreement on what the role should be up front. As the CEO, you are responsible for turning input from the interview team into a clearly defined role for the MOC. Once you’re confident that your MOC reflects why you are hiring for this role, everyone else should align behind the MOC and commit to evaluating candidates based on the criteria laid out in that document. And though the team should commit to hiring a candidate based on the MOC, the CEO should know going into the search that not everyone will agree on which parts of the MOC to prioritize or who to hire at the end of the process. The CEO must make the ultimate decision, get everyone else on board, and then set up the new executive for success. (More on this in the Onboarding and the first 30/60/90 days section.)

The level of clarity provided by the MOC sets the foundation to attract stronger candidates, provide a consistent candidate experience, shorten the hiring process, and better integrate new leaders into the org. The best candidates will be those with the highest probability of accomplishing more than 90% of the outcomes in the MOC. For instance, if you know that you want to hire a CRO to expand internationally with strong channel partnerships, a CRO from a $200M business with complex original equipment manufacturer (OEM) partnerships and channel sales is more likely to succeed than a CRO from a $1B business based predominantly on a product-led motion.

Sample MOC for CFO

Choosing a recruiter

At the beginning of the hiring process, one of the first decisions to make is whether to use an external search firm. In our experience, most companies opt to work with an external executive recruiting firm, though we’ve seen both internal and external recruiters make successful hires. Internal recruiters may know the company better, but they might not have the necessary network to recruit the desired profile, or may have their hands full with director- and manager-level searches.

Your recruiter will potentially be the first and primary touch point for candidates. Once you hire the recruiter, you should meet with them regularly—ideally weekly. The best recruiters are active participants in the interview and reference process and help with communication through negotiations and candidate onboarding. Search firms aren’t cheap: you’re paying for access to the right network, commitment to a process, evaluation of candidates, and general counsel on why different candidates are and aren’t a good fit. You want to take the time to review profiles and make sure they can accurately represent and assess what you are looking for. The firm can then perform the initial screening and present a small number of qualified candidates to interview and choose from.

A good executive search firm should:

- Meet weekly with you to develop a deep understanding of your business, your culture, and how the role will impact your company.

- Translate the MOC into a job description with clear “must haves” and a detailed description of what will define success in the first year.

- Give verbal and written reports on the search progress, including scope of the research and feedback from candidates about how the company and team are perceived in the marketplace. The latter is an important value-added service that is often overlooked.

- Run a thorough evaluation of potential candidates, including in-depth personal interviews to understand the candidate’s motivations and interest in the company, verification of credentials, and reference checks, before setting up candidate interviews to assess the candidate’s strengths and weaknesses.

- Create a strategy for candidate meetings and interviews. Not all candidates will walk in asking for the job. Before the team interviews a short-listed candidate, the search firm should circulate a written report and evaluation that focuses on the candidate’s past experiences as relevant to the proposed role, as well as their motivations in looking at a new role.

- Provide counsel and accurately represent compensation bands to candidates.

- Perform comprehensive reference checks throughout the hiring process, not just at the end.

Factors to consider

In an $8.8B industry with thousands of different firms to choose from, how do you decide which firm is the best fit for a given search? Below are some of the most important questions to consider when bringing on an external search firm.

Can they represent your brand? The search firm you work with is an extension of your brand and will represent your company to high-profile executive talent. Above all, it’s important to trust that they can be good representatives for you and your company. Can they accurately represent your business and values?

Can they tap the talent networks you need? What geographies, industries, and functions do they specialize in? It’s impossible for any single search firm to stay relevant across different functional areas and industry segments such as fintech, AI, web3, consumer marketplaces, B2B, and healthcare. The best way to know if a firm is right for your search is to ask for a list of similar searches they’ve recently performed. That will give you a good sense of what types of leaders they’ve worked with, and in which industries.

A firm’s size is less important than their overall capability and capacity to identify and recruit the best possible candidates while providing a stellar candidate experience. In fact, when we run searches at a16z, we tend to prefer boutique firms that specialize in a particular industry or function. For instance, if we’re hiring an HR leader, we seek out search partners that specialize in HR and only run searches for HR talent.

You also want to check that the firm can support recruiting from relevant geographies for your business. Again, size is not always the best indicator—there are many boutique firms that operate on a national scale, while there are multi-office firms with regional focuses.

Who is off limits? Search firms agree to not solicit people out of a client company for a certain length of time after they place a candidate. You should ask if the search firm has off-limits agreements with any of the target companies from which you’d like to recruit talent.

Who is your specific recruiter, and what’s their track record? In some firms, the initial consultants you talk to may not be the same consultants who work as your executive recruiter. Especially in larger firms, less experienced associates might conduct initial calls to candidates, while more experienced partners step in later in the search process. It’s important to ask up front: who will be working on your search, and in what capacity? Who is responsible for calling, interviewing, researching, and counseling candidates?

When assessing individual recruiters who might manage the search, consider:

- Can you trust the recruiter to manage high-stakes relationships?

- Can the recruiter effectively communicate the role and present your company?

- Do they understand the industry and functional role well enough to make sound recommendations?

- Can they assess potential candidates and determine who is and isn’t a fit for the role?

- Will they hustle to get you in front of candidates who are in high demand?

- How many other searches are they doing? Typically this should be 4–6, though in some cases with a good supporting team, a recruiter may be able to handle 6–8. A reputable firm will tell you up front if they don’t have capacity to take on your search.

The best indicators of a recruiter’s excellence are their dedication to a great process, their access to a high-quality network, their familiarity with and understanding of the candidates, and their track record of placing candidates who are successful in their roles. Search completion rate and repeat clients are two of the best signs of a strong track record. You can also ask a search firm for a list of references, including candidates they’ve placed and companies they’ve worked with. We often find it helpful to ask about searches that did not result in a placement or took longer than usual, and to talk with those references. Even the best recruiters have tough searches, and how they handled those searches will reveal a lot about their hustle and commitment.

Contract terms

Before the search firm begins your search, there should be a contract, written documentation outlining the position you’re hiring for, a scope of services, an identified search manager, a general timetable, and a statement explaining fees, expenses, and cancellation policy.

A few specific considerations to keep in mind:

Retainer or contingency. With a retained firm, you agree to pay the firm to complete a process until a candidate is in the role, regardless of whether the candidate was found by the search firm itself. In many cases, the fee is paid in full before a candidate is placed. Meanwhile, a contingency firm only earns their full fee when a candidate they sourced is hired. Some firms use a hybrid model, in which companies pay a small retainer up front, then pay the remaining fee after placing a candidate.

Fee structure. Fee structures can get very complicated. Generally, simpler is better. At a high level, we don’t recommend milestone payments on candidates produced because it may incentivize the firm to present more candidates, without necessarily identifying the best candidates for the search criteria. If you’re keeping a firm on retainer, make sure the retainer payment over time accurately represents how long the search is anticipated to run. For example, full payment due in 60 days for most searches is far too short; we usually recommend 90–120 days.

Guarantees and liabilities. A retained search firm is typically on the hook until the search is done, but there are often a lot of contingencies in these contracts. For instance, a search firm may limit the retainer to 6 months and after that point impose a new fee. Or if your job requirements materially change, firms may have a clause in their contract that allows them to charge a new, separate fee because they might need to start the search over. It’s important to establish an understanding of the firm’s policy in case of unusual situations. Under what conditions and time frame will a firm replace a candidate who leaves voluntarily or involuntarily? If your company hires a candidate, now or later, for a position other than the assigned search, what is your financial obligation to the search firm? What are the factors that may cause a search firm to withdraw from an assignment or consider the job specifications to be sufficiently changed to warrant starting a new search?

Interviews and working sessions

A well-run interview process gives you a 360-degree view of the candidate while granting the candidate a chance to build relationships and organizational context before they walk in the door on day 1. But what makes a well-run interview process? In our experience, it’s key to intentionally select who interviews the candidate and specifically assign each member of the interview committee something to assess.

There’s no set number of interviewers to include, but limiting the team to 3–4 people usually offers a better candidate experience. Of course, candidates can and sometimes do ask to interview with more people, especially if they reach the final stages and want more context before making a decision.

When selecting interviewers, consider who will have an active hand in the new executive’s success and who has the background, experience, and elevated intuition to evaluate specific skill sets, functional expertise, and ability to work well within the company’s culture and existing leadership team dynamics. For instance, if you’re hiring a CHRO and want to assess their judgment in high-stakes situations, your general counsel might interview them with a focus on how they decide whether a situation warrants seeking legal advice.

In some cases, an individual contributor (IC), rather than another executive, may be the best person to evaluate a particular skill set. This is often the case when hiring technical leaders, such as an SVP of engineering, where a senior IC engineer may be most able to assess their technical abilities and make sure they’ll be able to garner the respect of the engineers they manage.

Tips for interviewing

A candidate’s experience of the interview process is largely determined by how well you execute on details: Do they know where they are in the process? Are you respectful of their time when scheduling? Do they have the opportunity to ask questions to make sure the role is a fit for what they want? Are interviewers coming prepared with a clear sense of what they are evaluating? How do you capture feedback from interviews? Are you able to make timely decisions about when to advance a candidate or part ways?

We’ve found the following tips and best practices important for effective interviewing.

Start the conversation about compensation during the screening calls. A recruiter will typically screen candidates first to weed out those who aren’t a good fit. As part of this process, they should address compensation upfront. It saves everyone time if the recruiter asks candidates what their salary expectations are in the first or second conversation. If your company’s budget and a candidate’s expectations are too far apart, there’s no reason to continue the conversation.

Beyond the initial screening, the recruiter should continue to talk about compensation throughout the hiring process. Executives recruited from bigger public companies, who haven’t worked at startups before, will probably require more consultation, especially around the value of equity (which we cover in more detail in the next post). The entire hiring process takes time, energy, and effort, and by the time you’re making the offer, there should be no surprises. The hiring company should know the type of package the candidate expects.

Note that, legally, hiring companies can’t ask candidates explicitly what they currently make, but you can ask about their expectations. If the candidate responds by asking for your compensation bands, you’re legally required to disclose your compensation bands.

Meet candidates before you send them to the hiring committee. Once a candidate passes the recruiter screening, we recommend that the CEO meet with the candidate, ideally 2–3 times. In the first meeting, you’ll want to sell the candidate on your vision and the role. Once they’re interested, you’ll transition to asking them questions—What are you running today? How did you build X?—to decide whether to move ahead in the interview process. In some cases, you may even want to schedule a third meeting to ask further questions before moving them ahead in the process.

Be creative with logistics. Part of the reason executive hiring can take a while comes down to scheduling and logistics. Executives who are currently working elsewhere will have to manage their own schedules, and getting creative about scheduling interviews can keep the process moving. For instance, consider conducting an interview over breakfast or flying a promising but more remote candidate out to run through a round or 2 of interviews in a single weekend.

If a potential executive would have to relocate for the role, bringing the candidate and their family to the area can help them to settle in more quickly if they are eventually hired. Often combining this with the final rounds of interviews works well and reduces travel costs.

It’s generally easier and more effective to test chemistry in person. While it might be logistically easier to interview candidates over video, especially at the executive level, there’s no substitute for in-person interactions. When deciding whether to conduct interviews in person or remotely, consider:

- How is your workforce distributed? Is your business 100% remote? Are you in multiple countries? Are your executives in one location? If your executives are together, it may make sense to bring the candidate to that location to meet everyone in person. If your executive team is distributed and remote, it may make sense to have a first round of virtual interviews.

- Do the interviewers, especially the hiring manager, feel they can build a relationship with a candidate over video?

- What does the candidate prefer? Most executives want to meet in person to get a feel for the environment and chemistry, so look at your own constraints, think through the sequencing of your interview process, and balance your needs with the candidate’s preferences.

Introduce finalists to the board, but set expectations. As a courtesy, we suggest CEOs ask the board to be involved in the interview process, especially if there are board members who have previously held that executive role or have specific expertise that may be helpful in vetting candidates. Typically, we suggest involving the board in the final hiring round, meeting 2 or 3 final candidates. Before the interview, set expectations. Do you want them to conduct an interview or are they stepping in to sell the candidate on the job? Typically it’s a combination of both, but be clear on how they can best help you.

Check for core competencies. While the specifics of what you evaluate in the interviews will depend on your specific MOC, we’ve identified 5 core competencies to evaluate in any growth-stage executive:

- Beacon for talent: proven ability to recruit and lead high-performing and diverse teams across different businesses. If there’s one thing you have to get right in executive hires who will scale your company, it’s picking people who can attract talent. One of the biggest failure modes of late-stage companies is the inability to hire fast enough. If you ask the best sales executives how they were able to scale their sales teams exponentially, for instance, they will tell you they hired great lieutenants who then went out and hired great teams. Scaling a company requires executives who can consistently attract and develop talent through balanced feedback.

- Critical thinking: the ability to think strategically about the business, much like the CEO does, and take calculated risk.

- Motivation: the ability to propel a team forward with optimism and a bias towards action. The best candidates can flex across motivational styles to motivate different people towards the same goal.

- EQ & self-awareness: the ability to wisely mediate differences of opinion and have a positive cultural impact on the organization.

- Influence: the ability to earn credibility within the organization. The best candidates are not thrown off by internal politics, are able to pick their battles, and know how to use their influence to win them.

Working sessions

Typically reserved for finalist candidates, working sessions address one of the most common misalignments we see in executive hires: a mismatch between the outcomes listed in the MOC and the resources and time an executive needs to drive those outcomes. At their core, outcomes = resources + time. Though working sessions can take a range of forms—from formal presentations to casual conversations—they all drive a shared perspective on the resources and time a candidate needs to be successful. Another way to frame this is: if the MOC outlines what you want your candidate to achieve, the working session aligns you, your team, and the candidate on how the candidate will achieve those outcomes.

These working sessions are also important opportunities for CEOs to test the candidate’s chemistry with the existing team. Business dynamics in venture-backed companies can change at the drop of a hat, so it’s also critical that CEOs use these working sessions to assess how flexible and adaptable your candidate is. For instance, let’s say your MOC has your VP of sales candidate both building a 25-person sales team and hitting $100M in ARR by the end of the fiscal year. Your VP of sales candidate might come in and say that there’s no way they can hit that revenue number, even if they hired and fully-ramped those net-new hires in 6 months—they need budget for 10 more SDRs. Depending on your priorities, you might need to circle back to your board and adjust your forecast, or you might find more budget to give that VP more headcount. The goal is to have a back and forth that ultimately aligns you, your team, and your candidate on what that candidate needs in order to get you to where you need to go.

Reference checks

Throughout the hiring process, you should always be selling the candidate on the role and checking their references. Often companies use reference checks to rubber-stamp a candidate they’ve already chosen to hire. But references aren’t perfunctory, and if you’re just treating them as a step in the process, you’re not doing them right.

Reference checks should happen alongside the entire process and be considered just as critical to your decision as interviews. We often spend just as long reference checking as we do interviewing executive candidates. Configured this way, reference checks help to:

- Verify information from the interview process.

- More fully and accurately assess a candidate’s strengths and weaknesses.

- Onboard the eventual hire, putting them in the best position to succeed.

Who should be a reference? And how many should you check?

You typically won’t ask a candidate for a formal list of references until you’re reasonably confident they’re a strong contender for the role and you see them as a potential finalist.

However, you’ll still want to run reference checks earlier in the process. This means looking for people you have in common and asking whether you can check in with anyone they’ve worked with that they mention in the course of the interview. For instance, if you ask about a project that went off the rails and how the candidate got it back on the rails, listen for who else was involved. Different people see events differently, and you want to verify the candidate’s version represents what really happened. If you hear a different story from a reference, keep talking to more people.

Once you’re confident the candidate is a strong contender, ask them to provide a list of people who can offer a 360-degree view of their strengths and developmental areas. This list should include not only peers, direct reports, and managers, but also individuals who partnered with the candidate externally, such as customers, partners, and vendors. Speaking with this broader group of people often provides a more well-rounded view of how a candidate interacts with people at different levels, both within and outside of an organization.

While there’s no hard-and-fast rule for how many people this list should include, in our experience, asking for 6–9 references is a solid baseline: 2 managers, 2 reports, and 2 peers, along with a handful of external references. (Note that this list does not include backchannel references, which we discuss specifically below.) This should provide enough people to talk with in order to identify patterns in the candidate’s behavior, accomplishments, and failures.

Once the candidate has provided this list, tell them who will be following up with their references and how much time that person will need with each reference—we’ve typically found that good reference checks take 20–30 minutes.

On backchannel reference checks

Backchannel references—contacting people who know or have worked with the candidate but were not provided as formal references by the candidate themselves—can yield candid feedback that you won’t get from referred references, but they also come with risks. If word gets out that the candidate has been interviewing for a different position, they and their employer may experience very real consequences. If you’re going to pursue a backchannel reference, be certain that the reference is highly trusted. In one instance, backchannel references told a candidate who was otherwise ready to accept an offer that they had been contacted as a reference. The candidate felt that their trust had been breached and ultimately pulled out.

To avoid backchannel references going sideways, just ask the candidate about people you might have in common and, if you’re interested in pursuing the candidate more seriously, explain that you’d like to talk with some of these people as initial references. Alternatively, simply tell the candidate that you may come across contacts of theirs during the search process, and ask whether you can get in touch with those people. Most candidates will agree.

Backchannel references can be used in parallel with the interview process—not solely before you make an offer—to corroborate what the candidate has said in interviews. Consulting LinkedIn, exploring personal networks, and tracking down former employees are typically the easiest ways to identify potential connections. A mix of references that includes backchannel references might include 2 manager references provided by the candidate along with 1 backchannel manager, 2 provided plus 1 backchannel peer, and 2 provided plus 1 backchannel subordinate references.

When reaching out to backchannel references, introduce yourself and your company, clearly state that you’re calling them as a non-referred reference, and ask if they’d be willing to speak with you about the candidate. Assure them that anything they say about the candidate will be taken into confidence. Then, move into discussing specifics. You can often be more frank and direct with backchannel references than you can with referred references, and backchannel references will often give you a less-biased, more direct read on a candidate. This can be extra helpful if reservations about the candidate have surfaced during the interview process or you want to corroborate the candidate’s characterizations of their work and experience.

Tips for running reference checks

A good reference check has 3 parts: confirm basic facts, learn more about the candidate’s working style, and pressure-test concerns.

Confirm basic facts. Confirming basic facts is simply fact-checking the candidate’s relationship to the reference, how long they worked together, and the candidate’s track record, titles held, skills and competencies, and performance and responsibilities within the organization. Note that there are legal limits to what you can and can’t ask a candidate as part of a hiring process, including their salary history. Consult with your HR team if you have questions about which regulations apply to you.

Learn more about how the candidate works. How the candidate worked in their previous role can help you understand their management and communication style, track record, strengths and areas for improvement, interpersonal skills, and general approach to getting things done. Start by telling the reference more about the role at your company and its responsibilities, so they can put their answers in context. If you’re hiring a product leader, for example, and want to know if the candidate can secure cross-functional stakeholder buy-in on a complex project, you might ask how they approached updating the product roadmap.

Pressure-test concerns. No candidate is a perfect match for any role, but you should solicit input from references on the candidate’s capacity to meet the key demands of the role.

For instance, perhaps the interview committee thought a particular candidate for an SVP of engineering hire had the technical skills to execute well in the role but didn’t have a lot of experience managing engineering directors. If that’s the case, ask references about the candidate’s capacity to manage director-level reports. Or maybe the interviewers suspected that the candidate overstated their role in a key product launch. If this is the case, you might ask about a recent product launch and the candidate’s role in that project.

Strike the right tone. References should feel able to speak freely about the candidate, so don’t openly criticize or lead with your concerns about them. Instead, open by providing context on your company, the role and its charter, and your company culture to help the reference frame their answers, and then tell the reference that you want to know as much as possible about the candidate.

We tend to start reference checks with very general questions, sometimes as simple as “tell me about this person.” The first things that come to mind are often some of the most unfiltered feedback you’ll get from a reference. Some other favorite questions:

- What was included in their last performance review—both the good and the areas of focus?

- Would you want to work with this person again? Why or why not?

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rank this person for this role?

Throughout the call, we recommend asking open-ended questions that prompt stories and specific details. If the reference leans too much on generalizations, ask for examples to illustrate those statements, and resist the temptation to fill in silences. References often come back with surprising feedback and anecdotes if you allow a pause for them to think. You can also call out long pauses and ask if there’s more to unpack.

Dig into bad feedback, but don’t over-rotate on an n of 1. Companies often fall in love with a candidate, or get tired of running a search and settle, in spite of receiving some less-than-positive feedback from references. If you receive a negative reference, take the time to do additional reference checks to better understand if that feedback was a single data point from someone with an ax to grind, or part of a pattern of behavior.

Onboarding and the first 30/60/90 days

As important as a good hiring process is, it’s just the first part of bringing on a successful executive hire. An effective hire includes beginning to onboard the candidate during the hiring process by helping them build relationships with key figures in the organization and gain context about the company and its goals.

Once you’ve made a hire, it’s critical to outline a 30/60/90 day plan that details what you expect of the candidate in their first months. You’ll want to have the bones of the 30/60/90 plan in place while the hiring process is still underway, and then the newly hired executive can provide input based on what they’ve heard and learned through the process. Ultimately, the goal is to set the executive up for a few wins in the first 100 days, since that’s the leading indicator that the hire will work out.

How many different things are you putting on the new person’s plate that are new things versus things they did in the past? I like to only add one new thing when coming into a new organization. They already have a lot to learn about your company and your product, so I would rather give them less to begin with and then add to it as opposed to give them more and risk that they can’t learn it all quickly enough.

—Peter Levine, a16z general partner

Before the executive walks in the door on day 1, your HR leader should ensure that the new executive has access to relevant company and org documents—such as org charts, budgets for compensation, equity guidelines, recent performance reviews for the existing team, an overview of revenue goals and business initiatives, and the most recent product roadmap—to get up to speed. HR should also create a list of people with whom the executive needs to meet, and make sure introductory meetings are scheduled and added to the new executive’s calendar. Additionally, having board members and the leadership team reach out to welcome the new executive is a nice touch, helping them connect to the company from the start.

We also recommend that the CEO or hiring manager schedule a daily meeting during the executive’s first weeks to provide them with the context they need to navigate their new role. This also gives you the opportunity to identify areas where the new executive is going off track and offer fast, direct feedback to help them course correct.

When you’re a CEO, particularly a founder-CEO, and you bring in a CFO or a head of sales, they actually know the domain better than you. You may think, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t micromanage them because they know their domain.’ But the danger with all outside executives is that they come into your company and they do the job that they did at their last company because that’s what they know how to do. That is almost always a big mistake because their last company and your company are very different. One of the things I used to like to do with new executives is just say, ‘For the two weeks every day at six o’clock, you and I are going to sit down and I want to know everything you did today. Do that and you get a real feel if they’re off track.

—Ben Horowitz, Boss Talk #4

Next, let’s look at Executive Compensation.

Further reading

We’ve drawn insights from some of our previously published content and other sources, listed below. In some instances, we’ve repurposed the most compelling or useful advice from a16z posts directly into this guide.

What Now? Hiring, Peter Levine

You certainly don’t want to make a poor executive hiring decision, which is why you need to design a process that can assess a candidate’s fit, motivations, and expectations. Learn which steps you need to take to increase your overall hit rate and hire the right candidate for the job.

Hiring Executives: If You’ve Never Done the Job How Do You Hire Somebody Good?, Ben Horowitz

Hiring for a job you’ve never done will be necessary as you look to scale your executive bench. Here, Horowitz outlines a process to help you determine what you want, figure out if your candidate is a match, and make hiring decisions that only you, as the CEO, can make.

Hiring is Hard–Here’s How to Do it Right, a16z podcast with Caroline Horn and Matt Oberhardt

Every company needs a defined process for attracting and retaining talent. Horn and Oberhardt, both part of our Executive Talent team, discuss timing, how to launch a search, and how to create an efficient and attractive process to close the deal with your chosen candidate.

Finding and Hiring for (Expectations) Fit on Both Sides, a16z podcast with Gia Scinto and Jeff Stump

There’s no such thing as a perfect match. By taking a methodical approach to identifying expectations and motivations on both sides, you can make the right hire in spite of those imperfections and put your new executive on a 100-day plan for success.

On Micromanagement, Ben Horowitz

Is it wrong to micromanage executives? Sometimes. However, micromanaging new executives at the right time can set them up for success because it’s unlikely that they have a deep understanding of your market, your technology, and your company. They need information and it’s your job to provide it.

It turns out that just about every executive in the world has a few things that are seriously wrong with them. They have areas where they are truly deficient in judgment or skill set. That’s just life. Almost nobody is brilliant at everything. When hiring and when firing executives, you must therefore focus on strength rather than lack of weakness.

Who? The A Method for Hiring, Geoff Smart

Hiring mistakes are costly, but you can take steps to avoid them. In this book, Smart compiles advice from CEOs, investors, thought leaders, and more and outlines a 4-step process to increase your hiring success rate.