As much as we depend on our gadgets and their accompanying software to do more of our daily tasks—from reminding us to go to meetings to crunching stats for our favorite sports players—human intelligence is far from obsolete. On the contrary, MIT computer science professor Rob Miller believes there will always be a margin between what humans understand and what computers can do.

He provides the following example: Give a computer a paragraph of terribly hard- to-read handwriting, and today no available algorithms can decipher the scrawls. But give it to a group of people, and with each other’s help, they’re able to fairly accurately glean words from the seemingly unreadable.

“There are a bunch of things that human beings can do that we don’t know how to model with computers,” Miller says. “One of those is bottom-up and top-down perception. With the handwriting example, you look at an individual stroke or mark and are able to say that looks like an ‘e’ or ‘a’ or ‘i.’ That’s bottom-up perception. But then top-down is the context around it. Is it by itself with white space around it? Well then it’s not an ‘e’. That’s actually where multiple people tend to help each other.”

Miller studies human-computer interaction, specifically a field called crowd computing. A play on the more common term “cloud computing,” crowd computing is software that employs a group of people to do small tasks and solve a problem better than an algorithm or a single expert. Examples of crowd computing include Wikipedia, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (where workers outsource projects that computers can’t do to an online community) and Facebook’s photo tagging feature.

But just as humans are better than computers at some things, Miller concedes that algorithms have surpassed human capability in several fields. Take a look at libraries, which now have advanced digital databases, eliminating the need for most human reference librarians. There’s also flight search, where algorithms are much better than people at finding the cheapest fare.

That said, more complicated tasks even in those fields can get tricky for a computer.

“For complex flight search, people are still better,” Miller says. A site called Flightfox lets travelers input a complex trip while a group of experts help find the cheapest or most convenient combination of flights. “There are travel agents and frequent flyers in that crowd, people with expertise at working angles of the airfare system that are not covered by the flight searches and may never be covered because they involve so many complex intersecting rules that are very hard to code.”

Social and cultural understanding is another area in which humans will always exceed computers, Miller says. People are constantly inventing new slang, watching the latest viral videos and movies, or partaking in some other cultural phenomena together. That’s something that an algorithm won’t ever be able to catch up to. “There’s always going to be a frontier of human understanding that leads the machines,” he says.

A post-employee economy where every task is automated by a computer is something Miller does not see happening, nor does he want it to happen. Instead, he considers the relationship between human and machine symbiotic. Both machines and humans benefit in crowd computing. “The machine wants to acquire data so it can train and get better. The crowd is improved in many ways, like through pay or education,” Miller says. And finally, the end users “Get the benefit of a more accurate and fast answer.”

Miller’s User Interface Design Group at MIT has made several programs illustrating how this symbiosis between user, crowd and machine works. Most recently, the MIT group created Cobi, a tool that taps into an academic community to plan a large-scale conference. The software allows members to identify papers they want presented and what authors are experts in specific fields. A scheduling tool combines the community’s input with an algorithm that finds the best times to meet.

Programs more practical for everyday users include Adrenaline, a camera driven by a crowd, and Soylent, a word processing tool that allows people to do interactive document shortening and proofreading. The Adrenaline camera took a video and then had a crowd on call to very quickly identify the best still in that video, whether it was the best group portrait, mid-air jump, or angle of somebody’s face. Soylent also used users on Mechanical Turk to proofread and shorten text in Microsoft Word. In the process, Miller and his students found that the crowd found errors that neither a single expert proofreader nor the program—with spell and grammar check turned on—could find.

“It shows this is the essential thing that human beings bring that algorithms do not,” Miller said.

That said, you can’t just use any crowd for any task. “It does depend on having appropriate expertise in the crowd. If the text had been about computational biology, they might not have caught the error. The crowd does have to have skills.” Going forward, Miller thinks that software will increasingly use the power of the crowd. “In the next 10 or 20 years it will be more likely we already have a crowd,” he says. “There will already be these communities and they will have needs, some of which will be satisfied by software and some which will require human help and human attention. I think a lot of these algorithms and system techniques that are being developed by all these startups, who are experimenting with it in their own spaces, are going to be things that we’ll just naturally pick up and use as tools.”

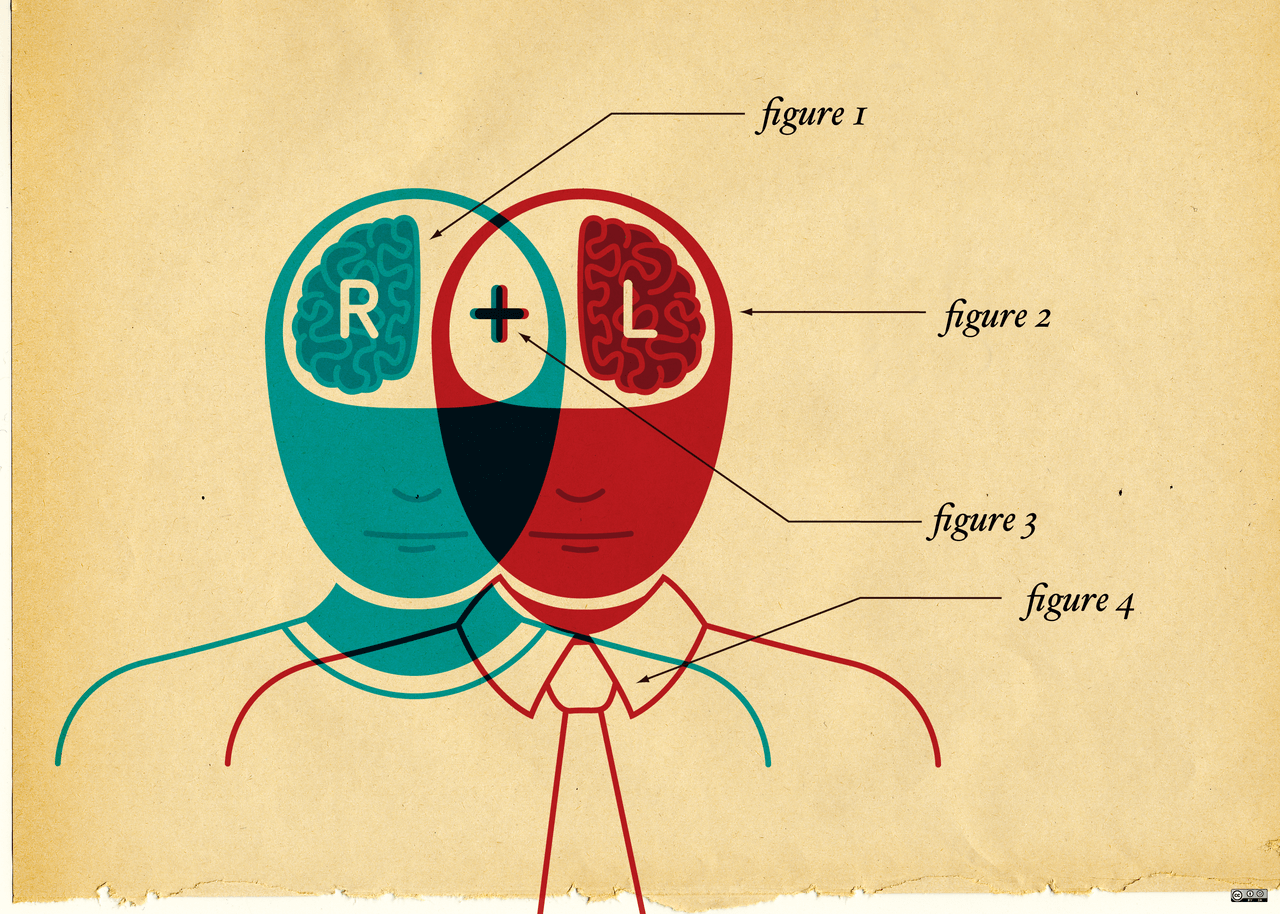

A dystopian future where machines totally overtake humankind, so often depicted in movies like I, Robot and The Matrix, is just that—fiction. “Human intelligence and machine intelligence is an incredible symbiosis,” Miller says. “Software isn’t eating the world by itself. There are people using that software. My argument is that there’s this triangle. A person needs more than just themselves. A crowd of people can actually eat an individual expert. The symbiosis of all three of these—end user, great software, and small contributions from a whole lot of people—will be a whole lot more powerful than any pair of those.”

This story originally appeared in The Atlantic.

- a16z Podcast: The Art of the Regulatory Hack

- a16z Podcast: On Corporate Venturing & Setting Up ‘Innovation Outposts’ in the Valley

- a16z Podcast: Connectivity and the Internet as Supply Chain

- a16z Podcast: Infrastructure… is Everything

- a16z Podcast: Open vs. Closed, Alpha Cities, and the Industries of the Future