Stop and think for a moment about how many ads you saw in the last 24 hours, on Instagram or Facebook or anywhere else. How many did you scroll through and glaze over? What if the number was capped at 2 or 3 a day? How would that change how you felt about the platform? Similarly, think about how many subscriptions you’ve signed up for—or forgot to cancel. What if, at the point of purchase, you had the option to only buy what you wanted, for the time frame you specified? This type of consumer power is the reality for netizens in China today—because Chinese internet companies have adopted business models that are drastically different than what we see here in the States, especially on mobile.

Product success is not just about having a good product, but also having the right business model(s). Expanding sources of revenue pushes us to think beyond what we know, and creates the infrastructure that opens up new opportunities. In this post, I will use consumer entertainment apps (books, podcasts, videos, and music) as a lens into the different business models and product strategies of Chinese companies. Thinking about content consumption in a mobile-first way in China has enabled these new business models, which not only provide diversified revenue streams for businesses, but also allow users to make better, more flexible purchasing decisions.

State of Affairs in the US

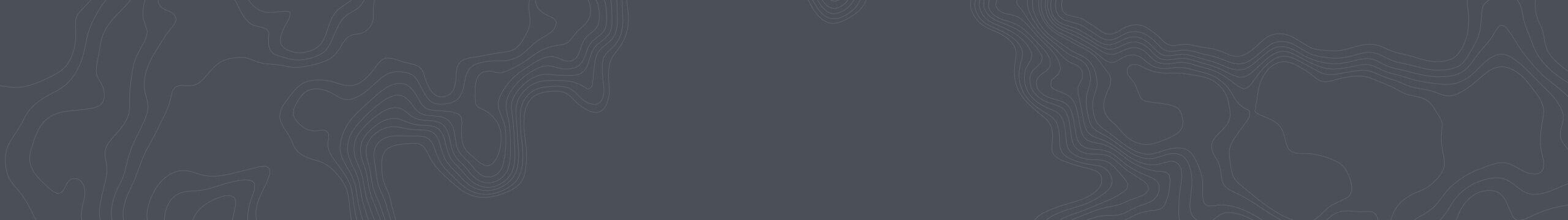

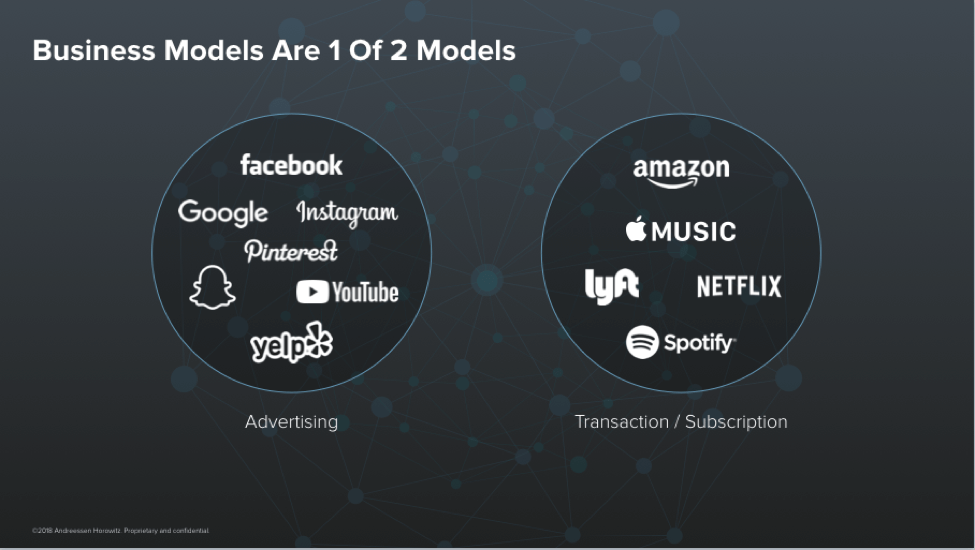

In the last decade, large consumer Internet companies from Google and Pinterest to Lyft and Spotify have become household names with market caps in the hundreds of billions of dollars. And yet, in terms of how these hugely successful companies monetize, these companies’ revenue streams are interestingly not very diverse. In fact, they generally fall into one of two buckets: advertising-driven, or transaction/subscription-driven. Revenue is heavily concentrated in one of these two business models, which in turn drives how the companies think about creating product. For example, advertising-driven companies focus on increasing engagement and time in app; transaction-driven services optimize for the lowest friction before checkout.

Put simply, apps in the United States are part of either the eyeball economy or part of the wallet economy.

It’s great for a company to focus, but is such a singular focus on one model for a revenue stream the best long term strategy for growth? And perhaps more importantly, does this lead to the best product for customers?

There are extremely compelling reasons to consider diversified revenue streams. Expanding revenue beyond ads allows for the simple fact that people’s preferences change. Digital marketing experts estimate that Americans are exposed to around 4,000 to 10,000 ads daily. There is a point where you can no longer stuff more ads down a consumer’s throat; ads become less effective and more annoying. Over time consumers may also not feel comfortable always being forced to pay for a ‘buffet’ with subscriptions, when in fact they only want one item on the menu.

There are also very strong reasons for combining the advertising centric world and the transaction world. Imagine if, as an advertising company, all of your ads could become one-click transactions: a win-win for advertisers, users, and the platform. If you are a transaction or subscription company, adding content and finding ways for users to increase time on your site leads to more mindshare and lower customer acquisition costs when expanding business lines.

What do these new business models look like?

Largely because many people could not afford a computer, China skipped the PC and the credit card; smartphones were the way many people were exposed to the Internet for the first time. So today, products aren’t just mobile first, many are mobile only. Mobile payments have penetrated the country and China has become a seamless digital society.

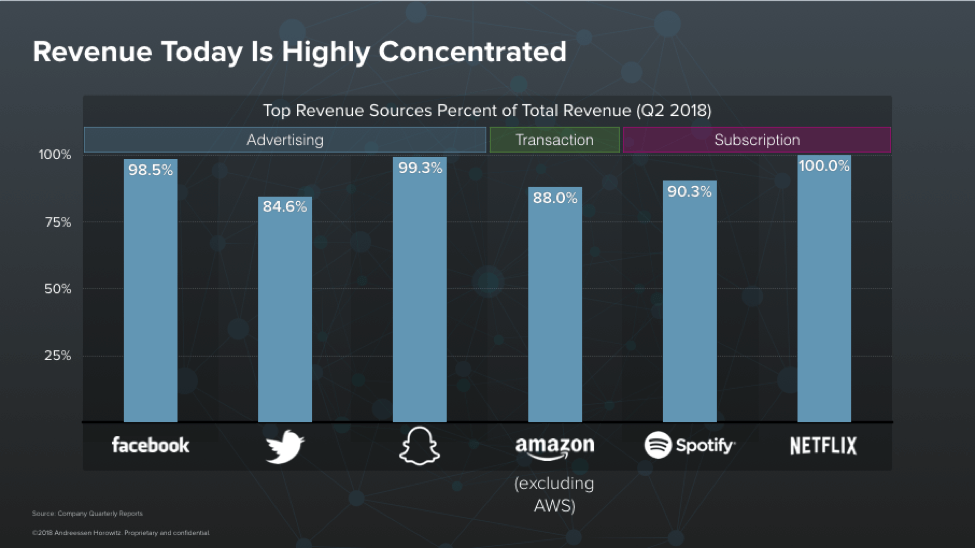

In part because a mobile ad is much more annoying on a small screen, the emphasis on advertising vs. other revenue streams is very different in China today than it is in the US. Due to the heightened competitive environment in China, platforms can not afford to not simultaneously seek alternative revenue streams and find ways to monetize without harming the user experience. Take Tencent, for example — a consumer internet company with skyrocketing revenue and a very diversified revenue stream — cloud/payments revenue is up 105% YOY; value added services for social networks are growing by 47%; and less than 20% of their revenue is from advertising. “We should not be overloading our users with ads,” said Tencent President Martin Lau in the Q1 earning call last year. As a result, ads in WeChat Moments (the equivalent to the FB newsfeed) are limited to just two per day. Tencent is able to hold that line on user experience because it has other ways of monetization. It’s hard to argue that the end result is not a better user experience.

As the products have got more sophisticated on mobile, business models with diversified revenue streams for content consumption — that rely neither solely on advertising nor transactions — evolved as well. This post will address four different content categories, with different consumer app sectors as case studies that illustrate not only how different the business models are, but also how the business models result in unique and ultimately better consumer experiences.

Books

In the United States, we typically buy digital books on Amazon’s website as one of several purchase options, in the same checkout flow as ordinary purchases.

In China, books are consumed very differently. In addition to their paid subscription service (similar to Kindle Unlimited), there are three main business models for book-selling in QQ Reading:

- Paid books allow readers access of up to ⅔ of the book for free. Readers have time to get hooked before they need to pay to unlock the ending. Think about how many more books you’d start if this were the case in the States!

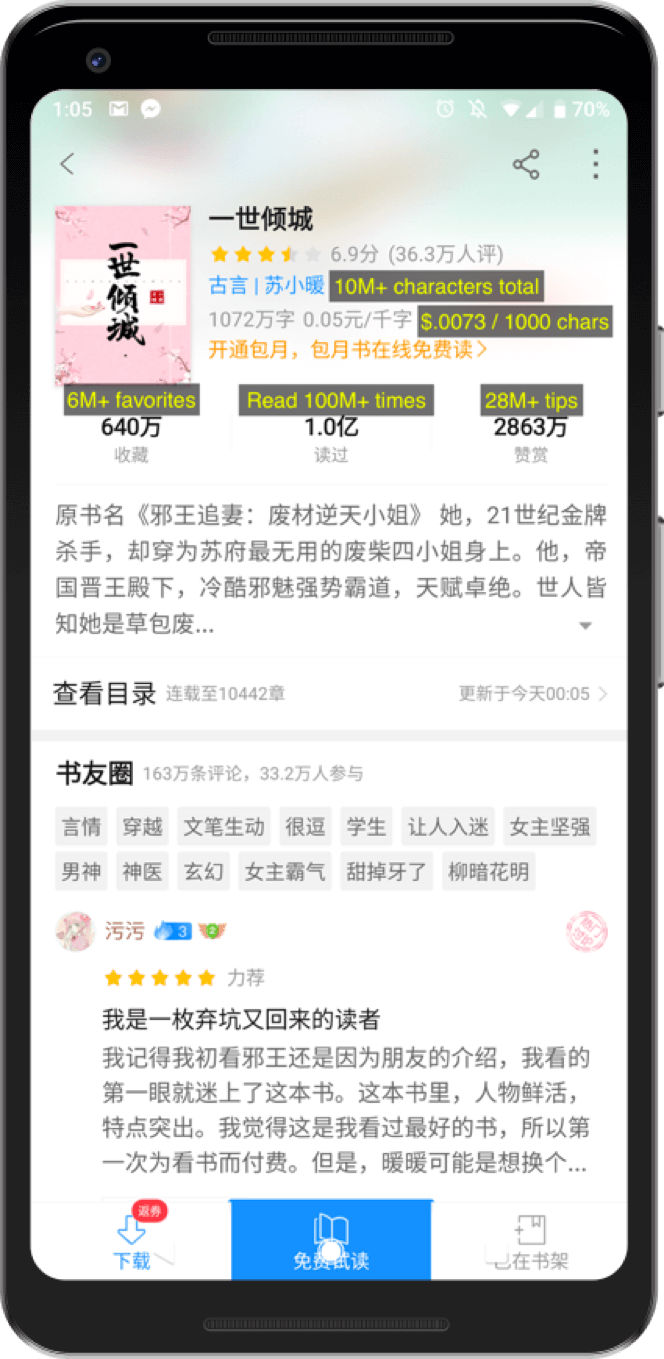

- Books are also sold as bite-sized snacks. Readers pay per 1,000 words, for often-serialized works. Below is a screenshot of one of the most popular books from 2014, 一世倾城. It has over 10,000 chapters and is still being updated — now more than 46 times the length of the entire Harry Potter series. Because authors can publish chapters piecemeal, they are also able to incorporate reader feedback to quickly change plots or even kill off characters.

- Some authors offer free books and illustrations, gain a loyal user base, and then collect money through tips. At the end of each chapter, an overlay button for tipping authors allows readers to tip from $0.15 and up.

Social elements and gamification also are combined to create a more enticing user experience. In WeRead, another one of China Literature’s reading apps, users compete against their WeChat friends on a weekly leaderboard showing who has read for the most time. It’s not just for bragging rights; users earn credits for every 30 minutes they read to spend on more books.

Search is also a much more complex and refined function in China, going far beyond best-sellers or sort-by-categories with granular, multivariable, smarter search options. Search is about discovery, after all — and the Chinese book platforms find ways to convey more information to customers, so they can find precisely what they want to read however they want to pay for it. For example, users can filter according to male or female readership, physical publications, or audiobooks. Then users can view custom curated lists including top trending, top new, top annual, most searches, free books with the most tips, and even according to times read cover-to-cover. These lists can be sorted weekly, monthly, or overall.

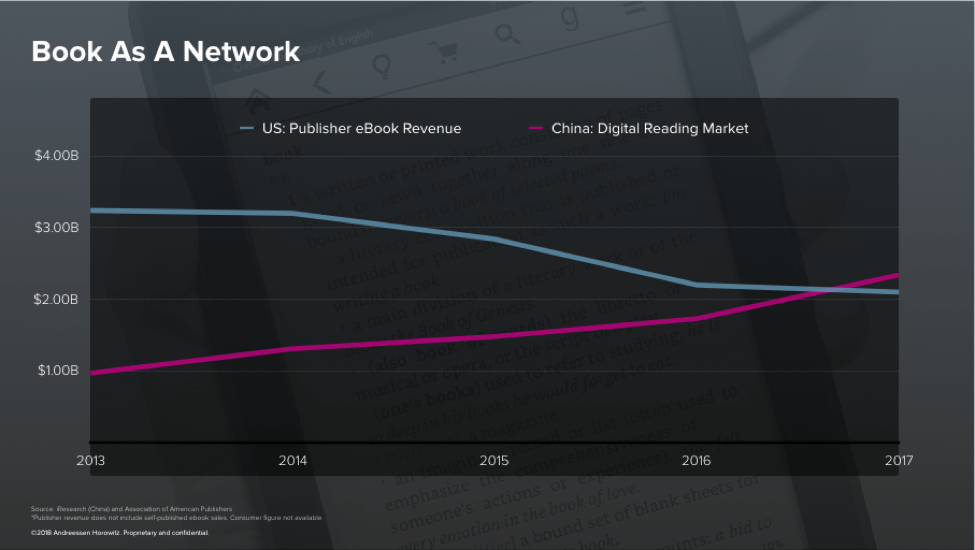

Importantly, in China, these book platforms also combine books from big publishers with books from up and coming self-published authors. So the way books are sold in China compared to the US is a major rethink of the publishing industry as well as a rethink of ebook platforms. In China, purchasing books is not about a one-time transaction for the platforms. There are elements of social media, gamification, and enhanced discovery — ultimately creating an experience that drives more sales. It all seems to be working. In China the ebook industry grew over 35% from 2016 to 2017; the same industry in the same time in the US trended the opposite direction.

Podcasts

The podcast Serial was downloaded 40 million times during its first three-month season in October 2014. This wildly successful spin-off of This is American Life likely perhaps earned up to one million dollars in ad revenue, according to the industry standard of $25 per 1,000 downloads. Revenue might even have been lower, as rates were negotiated well before anyone knew how successful the podcast would become.

Despite being deemed ‘podcasting’s first breakout hit’, revenue couldn’t cover the cost of producing a second season. The host/executive producer Sarah Koenig started asking listeners for donations during episode nine. In less than a week, enough donations poured in to guarantee a sequel, but the fact remains that advertising alone couldn’t support the big budget podcasts’ continued production even for the most successful podcast the US had ever seen.

The entire podcast market in the US in 2017 was $314 million, all from ads. Estimates for paid podcast in China, on the other hand, are $3-5 billion, and many individual podcasters are multimillionaires. It’s not a difference of talent; it’s a difference in business models.

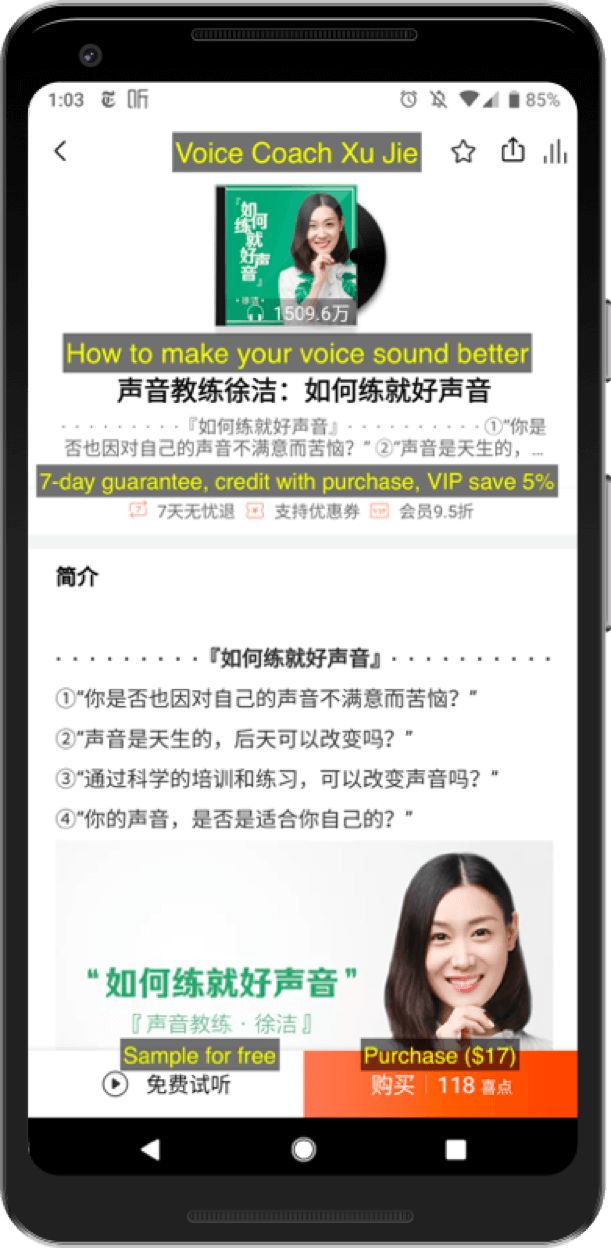

In China, many podcasts charge the end customer instead of relying solely on advertising. Some podcasts are part of the platform’s paid subscription service, but users always have the option to pay for podcasts individually. The following screenshot from the popular podcasting app Ximalaya is all about improving the sound of users’ voices. The podcast course is made of over 30 episodes, and costs around $17. The course has over fifteen million listens and has generated over $1 million in revenue.

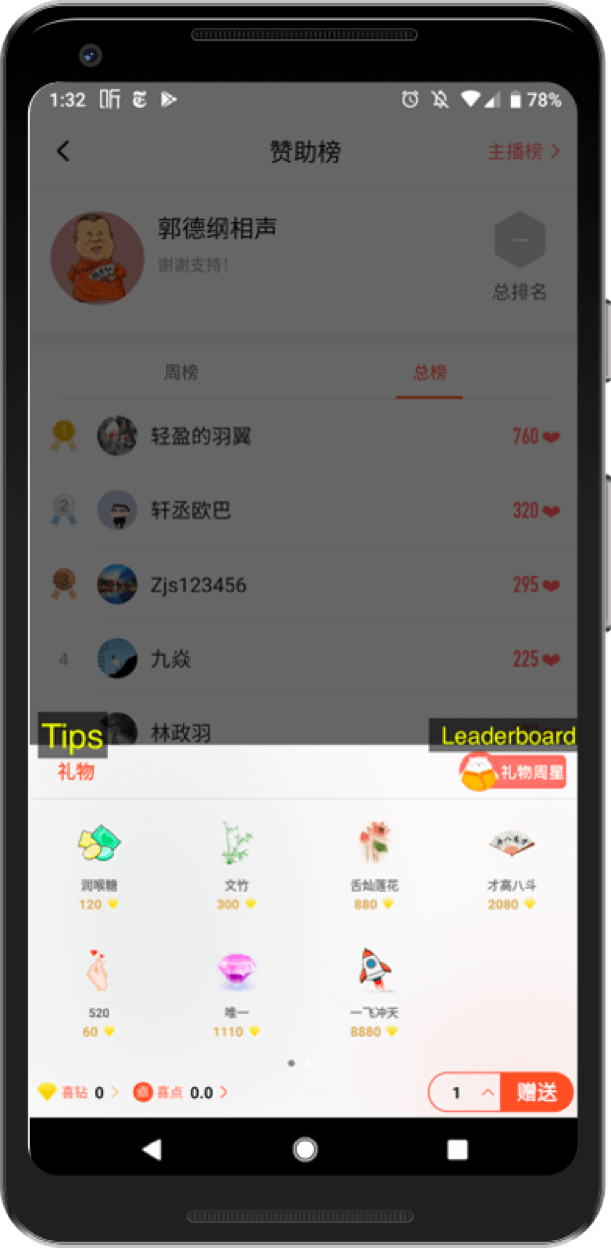

Just like digital books, free podcasts are monetized in several ways. Some podcasts rely on sponsorships and ads the way we do in the US, but podcast hosts can also receive tips that are split between podcaster and platform. In the following example, tip options vary from $.30 to $21. This new model means everyone can make money and content creators have more funds to invest in better production and better content; everyone wins.

The audio platform Dedao (“iGetGet”) essentially takes the MOOC format and applies it to podcasts. Below are two economics professors from Peking University. Xue Zhaofeng, the professor on the left, actually resigned after making $8 million in one year with his economics podcast series. The professor on the right has grossed nearly $5M in sales for her podcasts on financial literacy and wealth management techniques.

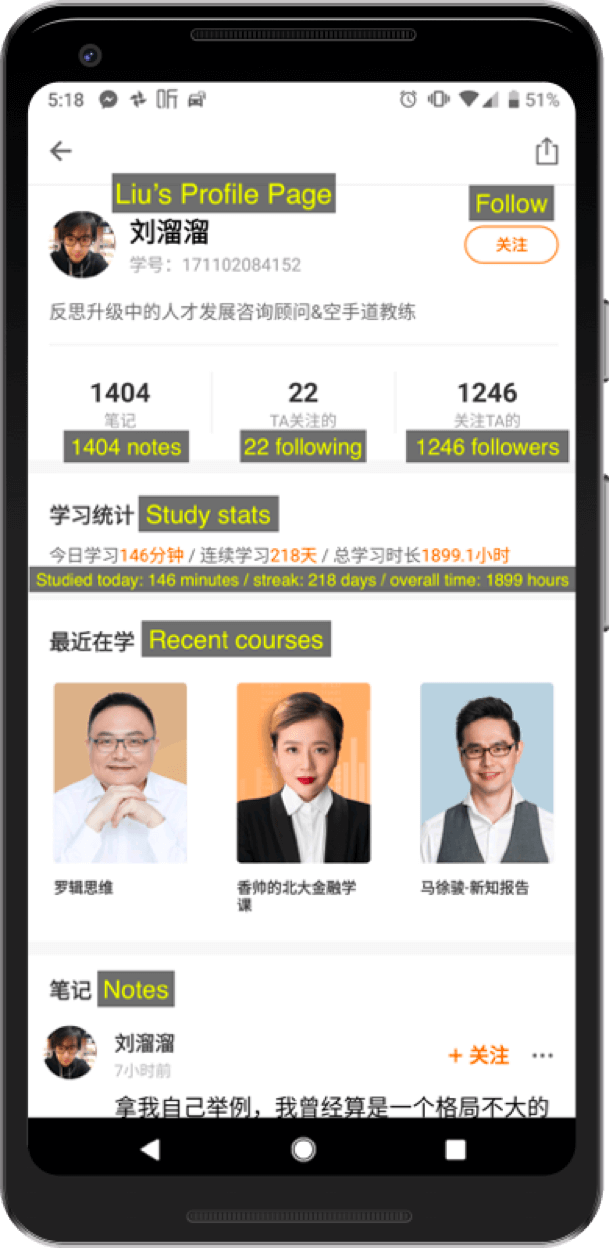

Beyond the scale and business models, what else makes these Chinese podcast platforms different from their Western counterparts? Similar to book platforms, these apps hook users through social elements and gamification. Ximalaya has a leveling concept, where you ‘level up’ by listening or spending money in the app to earn coupons and even limited-time membership to use their paid subscription service. Dedao hosts a social network based around studying, where users can create a public profile and share or compare course notes. Users can also leave public questions or comments at the end of each podcast transcript.

Studying podcast platforms such as Dedao or Ximalaya give us insight to how the podcast market here in the States can evolve beyond ads, and ultimately put more money in the pockets of our podcast creators. There is an expansive expert network that is untapped and not fully monetized in the States, not due to a lack of talent, but because of overly simplistic business models.

Video

In the U.S., this is what users typically see on YouTube when they first click on a video. Monetization is accomplished through pre-roll ads, display ads, and interstitial ads. Ads typically have nothing to do with the content of the video.

In China, Baidu spinoff iQiyi, one of the bigger video players, uses AI and machine learning to figure out what’s happening in the content, and play relevant advertising. In the following scene of a young professional putting on lipstick, for example, iQiyi serves an ad promoting a makeup brand. This makes product placement ads that much more valuable, and ads in general slightly more acceptable (screenshot from Ad+ Home).

iQiyi’s business model also goes beyond advertising with many other revenue initiatives. (Sneak peak: advertising is less than 50% of the company’s revenue). iQiyi has over 80 million VIP members, but membership is not an absolute paywall. Instead, members get perks such as discount coupons, no advertisements, and the ability to watch new releases up to 12 episodes faster. Some of the movies on iQiyi are member-exclusives; non-members can watch the first 6 minutes of the film before deciding whether or not to “unlock” the rest of it with a membership or pay à la carte for the movie. VIP membership rewards active users with perks that keep them engaged with the platform and inevitably spend more money.

VIP memberships also include exclusive access to app skins based on celebrities or popular shows. In the below skin from iQiyi-produced ‘Sing! China’, all of the navigation buttons are replaced with faces of the mentors/judges.

On iQiyi, users can clip digital coupons, such as the following BOGO coupons for Dairy Queen and Burger King. Imagine watching a movie on YouTube and getting a craving for pizza and hot wings, now you can immediately act on that craving.

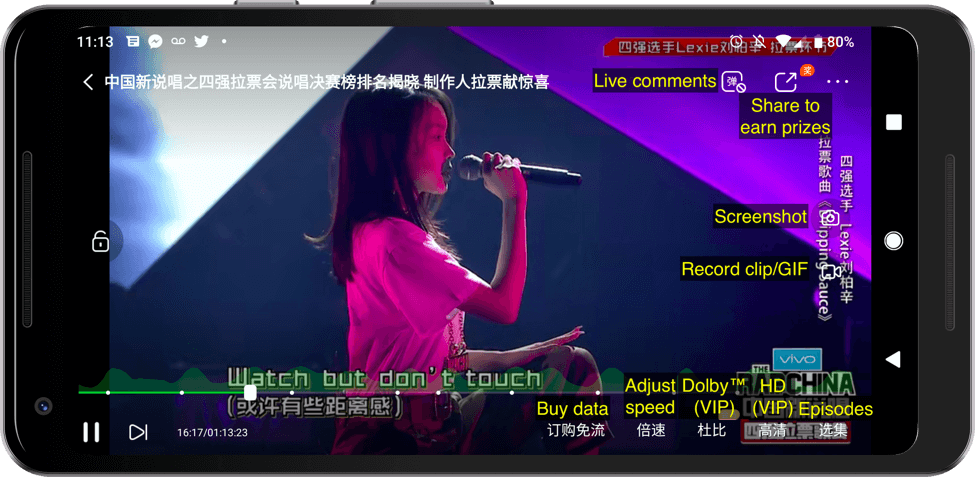

This is what the watch screen on iQiyi looks like. There’s live comments, sharing for prizes, GIF creation, and even the ability to top up your mobile data plan. Users are even upsold their VIP membership in order to access the higher quality audio and video. You could say this is too crowded of a page; you could also argue that this is a more advanced experience, where you can even create content to share on social media. If it’s too busy for you, all you have to do is tap to hide the settings overlay.

For many shows or movies, users can shop related items as they continue to watch; there is no need to stop the video. Rap of China viewers can buy Beats headsets as they watch, while users watching ‘The Great Wall’ movie can purchase custom movie merchandise while they’re engrossed in the film.

There’s even a social network component that lives entirely inside iQiyi. Users can join their favorite celebrities fan circles to chat about the latest celebrity news and gossip. The platform is a rich aggregate of content and can be used as a portal to watch shows, movies, social media, view upcoming meet and greet events, and even read news.

This social network that lives inside iQiyi is not just for celebrity news; there are more than one hundred fan circles based on iQiyi’s most popular content and all topics related to entertainment. In turn, the information from the social network gives iQiyi data on how to cast characters, evaluate scripts, and even predict show success. The social network increases app opens by 160%, and average daily watch time by 24%.

iQiyi’s business model has also extended to the real world with its recent launch of ‘on-demand movie theatres.’ These miniature theatres range from two to ten seats, and are rentable by the hour to watch any content from iQiyi’s library. It’s bringing the traditional movie theatre experience up to date in the era of streaming.

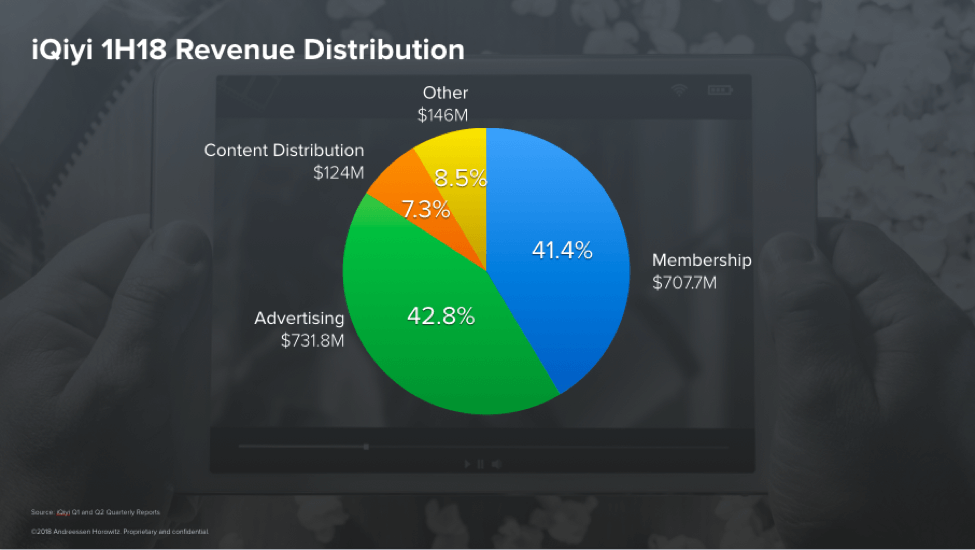

The result of iQiyi’s expansive business model is a diverse product strategy and diverse revenue streams.The below graph depicts the 1H18 revenue distribution, with membership and advertising in a dead heat.

However, this race did not stay even for long. In 3Q18, membership stayed steady at 41.2% of revenue, while advertising dropped to 34.6%. iQiyi has over 80 million paying members out of over 500 million total users, and is able to successfully monetize all users because of its expansive business model and emphasis on diversified revenue.

Music

In the US, we’re used to a monthly subscription fee on Spotify or free online radio where we listen to ads every so often. What happens when you take a music streaming platform and turn it into a social, lifestyle app?

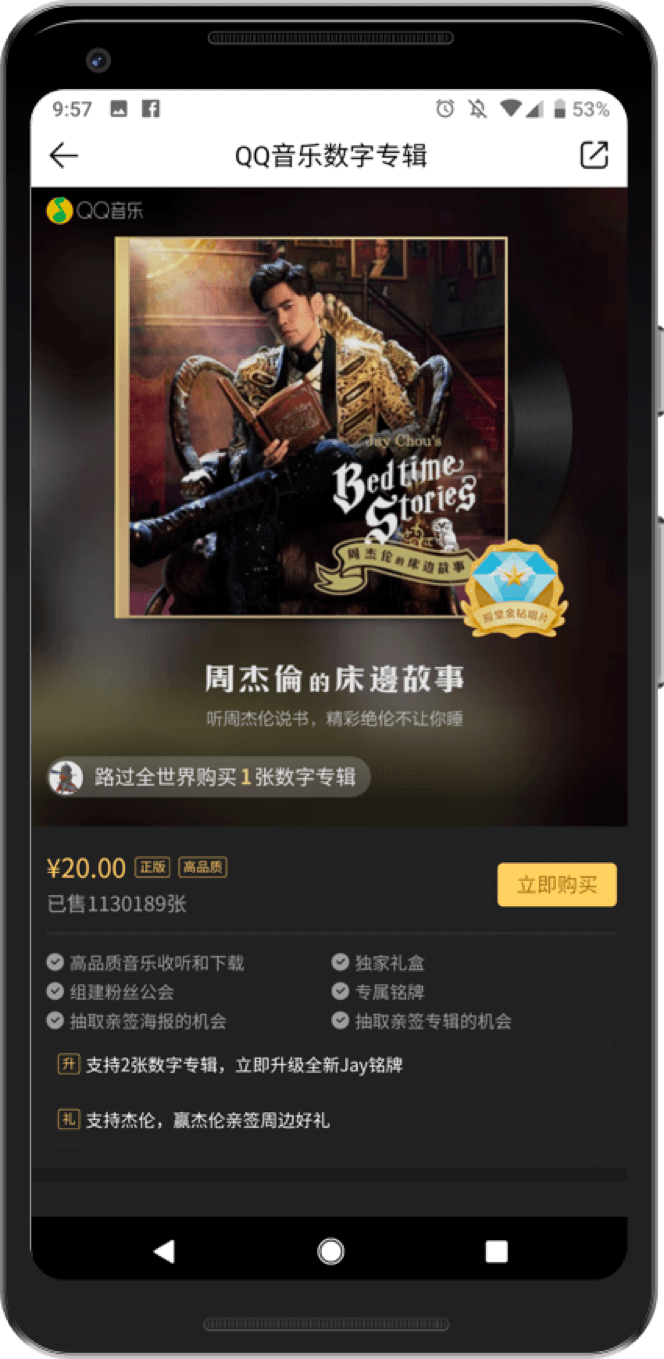

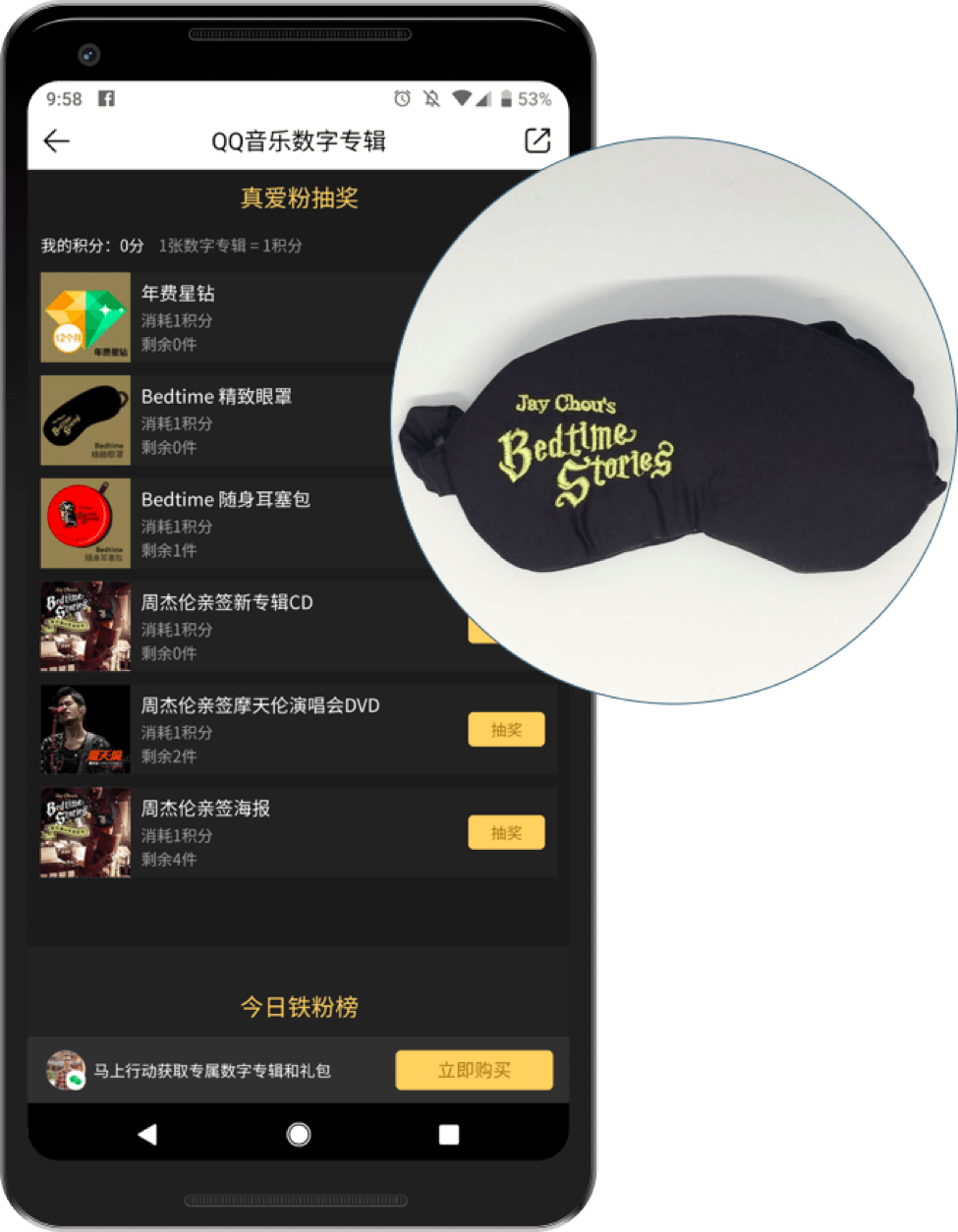

Tencent Music illustrates very well the extent to which Chinese music industry has rethought the entire business model. For starters, popular artists often have a limited-time streaming block on new releases. During this time period, users buy or gift virtual albums that provide exclusive access. Two years ago, pop singer Jay Chou sold limited time access to his album Bedtime Stories for less than $3. To promote competition among fans, Tencent Music created a leaderboard showing how many times fans purchased the album; the top user purchased the album over 400 times!

But you don’t have to top the leaderboards to get the benefits here. Say you bought that Jay Chou album 3 times; you might be ranked #3913 on the leaderboard, but worry not, you’ve also won 3 raffle tickets to win signed posters, VIP memberships, or even Jay Chou sleeping masks. This kind of gamification and reward system turns average fans into superfans, and gives superfans a deeper connection to the artists they adore.

The Tencent Music platform has multiple such methods of increasing fan loyalty and improving artist marketing for artists big and small. Similar to iQiyi, users can skin the app for a small fee. You can imagine how many Deadheads, Beliebers or Swifties here in the States might also be willing to pay a small fee to skin their media apps.

There is also a social network where small or medium artists can post articles, and fans can access news, music videos, and behind the scenes content. Artists are able to share more of their story and fans develop deeper loyalty. Artists simply don’t get this kind of fan support from Western music platforms.

If your interest is in live music, Tencent Music apps also have a feature for that. The app strives to be a hub for concerts and events so you can buy concert tickets directly within the app. If you can’t attend concerts in person, you can also watch live streams. In the screenshot below, the live stream concert by TFBOYS was watched over 36 million times.

In Tencent Music, there are leaderboards for gamification, social radio and singing, live concerts, and even a TMZ-type portal for discovery. In short, there are many ways for listeners to engage with music and the artists. But perhaps the biggest difference of all is that the company’s focus is not just listening and consuming music, but also creating content and allowing users to earn money. Anyone can create an online radio station within the music app and curate their own playlist. Hosts tell stories between songs, or give commentary on the lyrics. Good hosts earn tips in the form of digital gifts from listeners and get to keep 30% of the revenue.

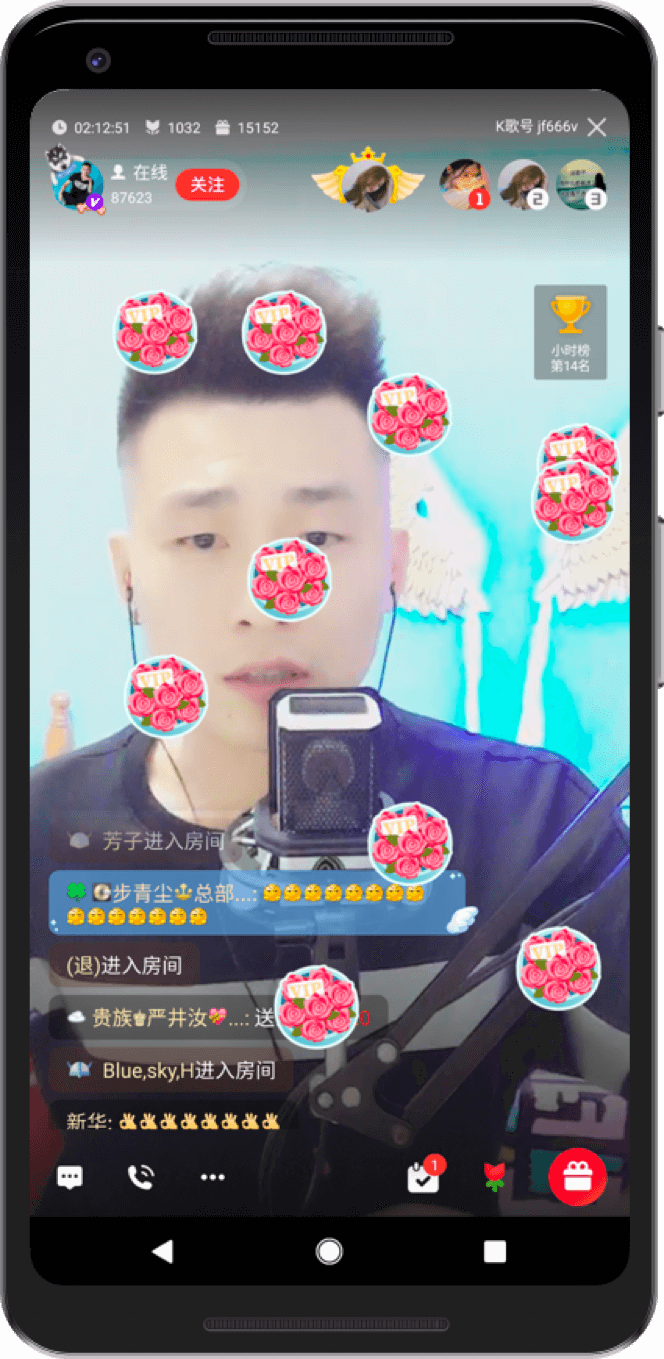

In Tencent Music’s other flagship app, WeSing, users can livestream their own karaoke room or open up the floor to anyone who wants to sing karaoke. Singers keep 30% of the tip revenue. It’s fun, social, and makes a lot of money for both platform and customer.

Lastly, Tencent Music is also taking its business offline. The company is not only selling microphones and headphones, but also opening up hundreds of mini karaoke booths in malls. They come complete with chairs, curtains, headsets, even air conditioning. Users have a blast in the booth, and then get a recording of the singing sent to their phone. (Image below of competitor Minik’s karaoke booth from journalist Zhang Cenyu).

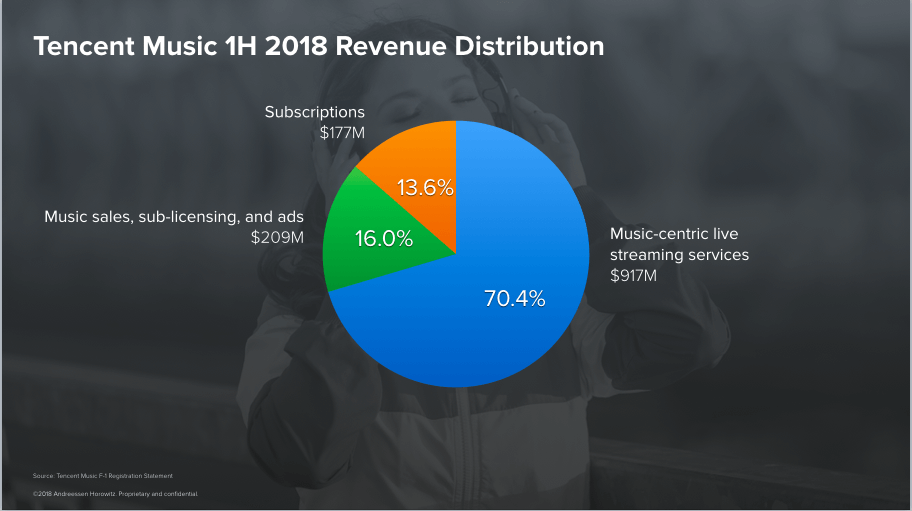

The result of such a nuanced business model is a whopping 70% of revenue comes from those live streaming services – tips for radio and karaoke. It’s a complete contrast from Spotify’s business model, of which 90% of revenue comes from subscriptions. All in all, Tencent Music’s business model transforms music from a solo consumption product to a lifestyle, sharable experience.

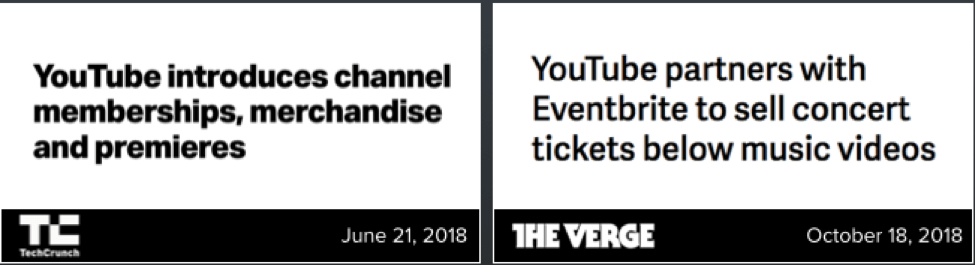

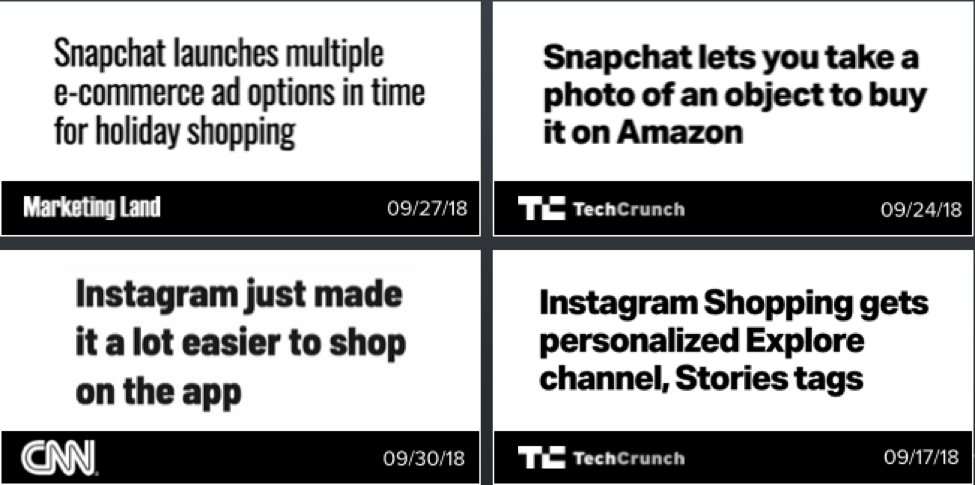

Where is the US headed?

Finding new ways to diversify revenue streams in China has led to very interesting product innovation for these companies. We are just beginning to see the same kind of thinking in the US. Amazon is one of my favorite examples. As Amazon dives more into content and advertisements, its ability to sell ads against viewer’s past purchases make their ads tremendously valuable. For instance, imagine Coca-Cola now being able to serve ads only to people who purchased Pepsi.

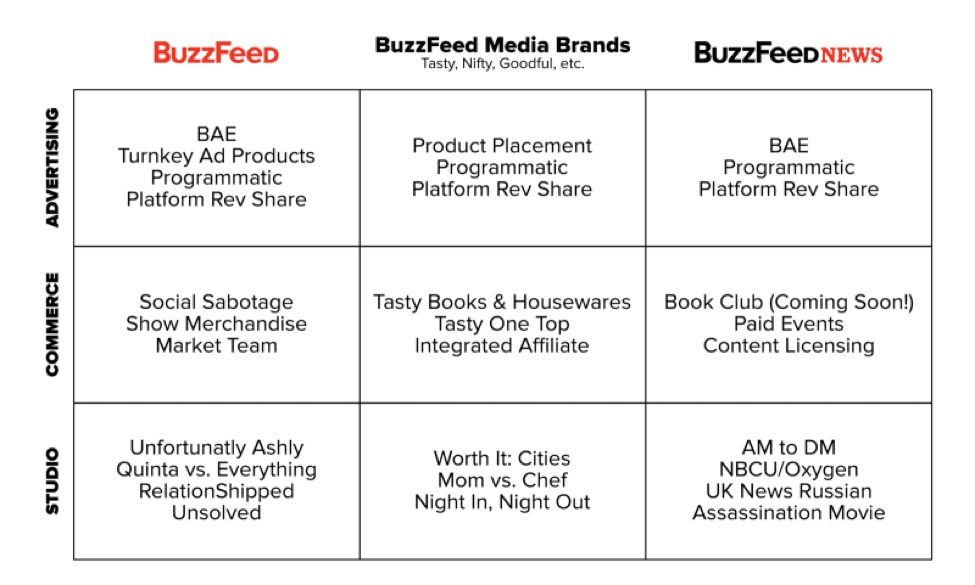

CEO/Founder of Buzzfeed Jonah Peretti (an a16z portfolio company) understands this shift. “We’ve outgrown the ability to build our business on essentially a single, very distinct revenue stream,” Peretti recently said. Buzzfeed — historically a media business that delivers news and makes money from ads — announced their push to diversify in late 2017. They’ve partnered with Walmart and Jet to sell branded kitchenware in a seamless purchase experience.

Their new business model is a 3×3 grid (below) in which Buzzfeed and related brands profit from three core revenue streams: advertising, commerce, and video entertainment. Jonah predicted that by 2019, half of the company’s revenue will come from outside of ads.

Going beyond “only”

In the past, revenue was often thought of as a result of product brilliance. Studying China illustrates how expanding sources of revenue, not just growing existing revenue lines, is a lens to drive product thinking. This idea of going beyond ads-only and transactions-only to diversify revenue streams can be applied to all kinds of sectors. Just think about some of the following ways in which we can adapt or integrate business models for the future: ads to subsidize ride sharing; live streaming, influencer reviews, and limited-time promos to drive e-commerce; gamification to promote healthier lifestyles. How much more fun could products and services be if they branched away from a singular business model?

History has taught us that not all established companies can make business model transitions. Will the current set of Internet companies make this leap to more personalized user experiences that are less ad- or transaction-centric? Perhaps, given all of this, FAANG could be more vulnerable than many think.

Expanding sources of revenue not only pushes us to think beyond what we know, but forces us to create the infrastructure to go after new opportunities. After all, revenue is simply a proxy for how you are serving your customers. As you diversify and experiment in generating revenue in new ways, you are effectively honing in on your ability to give customers what they want, how they want it.

Business models as a product strategy. It’s exciting to imagine what’s possible when advertising and transactions collide.

Thanks to Avery Segal for his research help.

Image Sources: Company Quarterly Reports; Tencent Q2 and Q1 2018 Quarterly Reports; amazon.com/Love-Languages-Secret-that-Lasts/dp/080241270X; Screenshots QQ Reading; iResearch (China) and Association of American Publishers; 2017 News Publishing Industry Internet Development Report / Ali App Distribution 2017 Q2 Industry Report / Marketplace; Ximalaya FM; SCMP /Jianshu; youtube.com/watch?v=dz-W7z78RFY; Screenshot Ad + Advertising; iQiyi; iQiyi (Paopao); iQiyi Q1 and Q2 Quarterly Reports; QQ Music / Rakuten; WeSing; Fortune Insight; Tencent Music F-1 Registration Statement; theverge.com/2018/8/28/17793620/amazon-fire-tv-ad-supported-video-service-free-dive-prime-members-roku-channel; recode.net/2018/3/1/17066402/buzzfeed-walmart-tasty-kitchen-gadget-tools-retail-deal