It’s no secret that widespread labor shortages are critically impacting the United States. In construction, companies can’t replace retiring workers fast enough and have started offering housing per-diems to attract workers. In education, states are recruiting candidates without teaching experience to fill open teaching roles. We can see similar shortages — and extreme employer responses — in nursing, transportation, trucking, and other industries.

Critically, these labor crises are not happening in isolation, and they have compounding effects. Staffing shortages put greater pressure on existing employees and catalyze disputes, walkouts, and strikes. Shortages also mean that federal funds are not being properly deployed. For example, the 2021 federal infrastructure bill allocated $1 trillion for infrastructure projects — meaning a lack of skilled construction workers directly hinders the construction of highways, transportation, and other infrastructure projects, and the third installment of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds has allocated $190 billion to schools.

Moreover, these labor shortages are likely to endure because they are based on generational factors. Many younger workers have a negative opinion of working in the skilled trades, and many parents perceive going to a vocational school as undesirable. Others feel societal pressure to go to a four-year college to “matter” in American society. Changing these mindsets will not be fast or easy, as it is now clear that building the American workforce will require building a culture of helping young people find meaningful work — a culture where working with your hands in critical industries is respected, desirable, and, in a word, cool.

These long-term trends are why it is critical to build solutions for the development of the American workforce now. Building American Dynamism requires a robust labor force to do the building. As we’ve said before, we believe startups are core to solving critical problems for the country; as such, we outline here three different models for how startups can directly and indirectly tackle our workforce crises.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

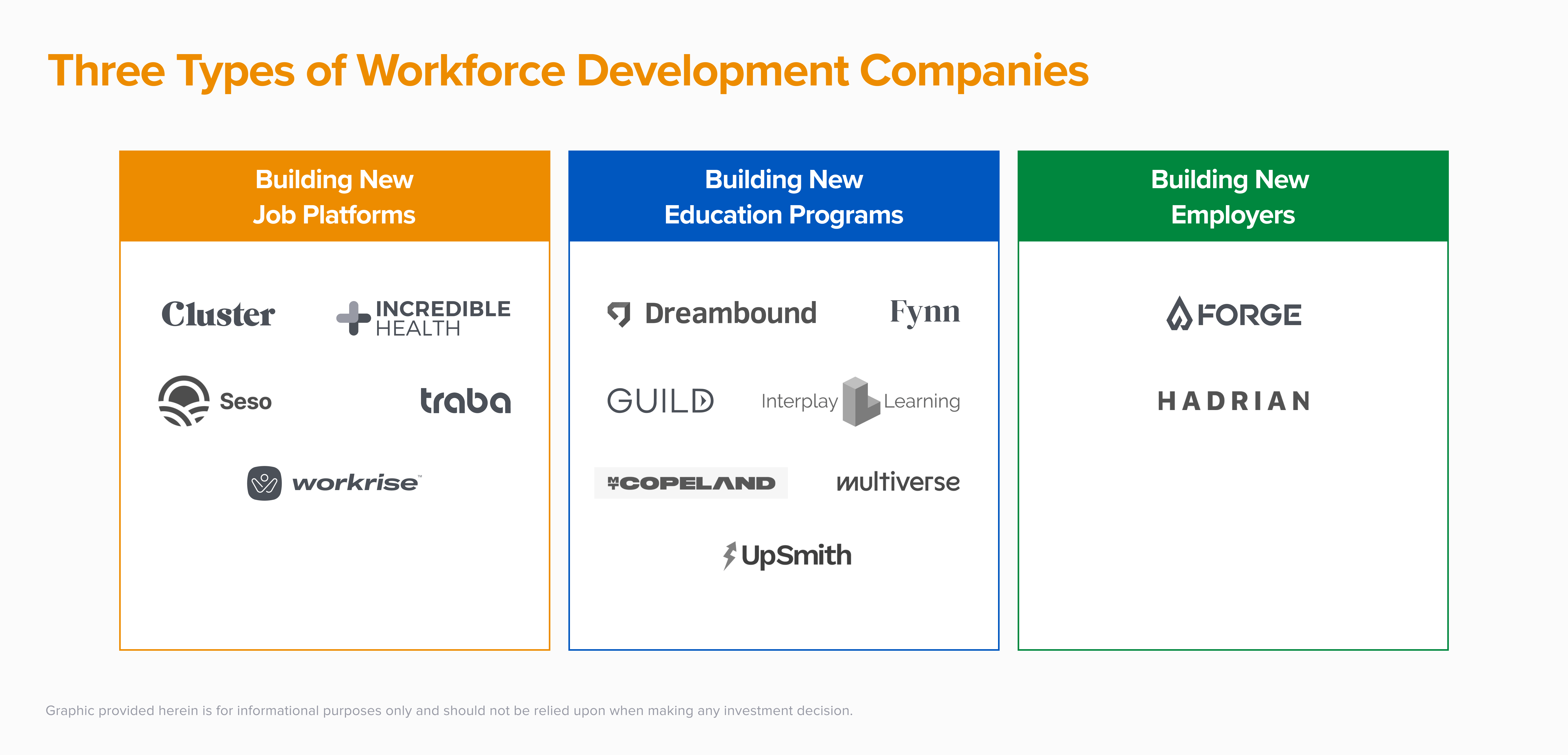

A Framework for Workforce Development Companies

Like “future of work” companies, workforce development companies are focused on addressing challenges in the labor markets. But unlike “future of work” companies, which are ambiguously defined to include a wide array of companies, the workforce development category is precisely focused on solutions that improve the quantity and quality of labor. Broadly, we think there are three models of workforce development companies that can affect labor markets in core domestic industries.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Building new job platforms

The first model of workforce development company is perhaps the most common: the vertical labor marketplace. To efficiently match workers to open jobs, these businesses focus on minimizing administrative red tape, increasing visibility of job and candidate information, and taking other measures to eliminate barriers for job seekers and job posters alike. These platforms thereby optimize supply and demand in labor markets.

By shifting away from using general job boards and toward managed verticalized marketplaces, modern workforce companies can offer their clients more targeted solutions to address their specific hiring pain points. For example, Incredible Health focuses on helping hospitals hire nurses; Traba focuses on hiring for shift-based workers in warehousing, logistics, and other light industrial sectors; and Workrise focuses on connecting skilled workers to operators and projects in the oil and gas and solar industries. Other verticalized marketplaces focus on particular professions. Cluster, for example, focuses on mechanical and electrical engineering roles across a number of industries like aviation, space, defense, and automotive. The common theme across these approaches is that by focusing on a specific type of role, these platforms are able to address industry-specific needs, nuances, and bottlenecks in hiring that are usually deprioritized by more general job board companies.

A more tailored approach to customer needs also enables additional workforce management tools to be layered into these platforms; this is called the “deep” job platform model. These tools, which are for employers and employees alike, can provide a long-term roadmap for hiring platforms. They also include services like human resources information systems, payroll, benefits, credentialing, applicant tracking systems, and more.

In addressing labor shortages, verticalized labor platforms work best when they can help streamline procedural, operational, or informational complexities. They are also well-suited for professions with more flexible work arrangements or shorter tenures, as well as with jobs where the labor supply can be flexed up and down relatively quickly (i.e., light industrial or agriculture jobs). Seso, for example, matches farms with agricultural workers and streamlines the visa process of hiring seasonal workers in the U.S., effectively helping bring new supply to the U.S. agricultural labor market. Finally, as their core competency is facilitating a match between employer and candidate, verticalized labor platforms are the quickest model for realizing improvements to the labor markets.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Building new education programs

The second model of workforce development company focuses on creating new supply of a particular profession or trade. These companies can be education or education-financing businesses, as these are the primary means by which companies can increase their workforces. The approaches these companies take to training, upskilling, or reskilling vary, as do their relationships with employers, who are often key stakeholders in these programs.

Some of these businesses focus on developing, delivering, or otherwise making accessible the curricula and/or credentialing used to train or upskill workers. For instance, Dreambound focuses on certified nursing assistants by helping candidates find suitable courses and managing the administrative, payment, credentialing, and hiring processes involved in the education-to-employment pipeline. Guild Education focuses on delivering upskilling curricula for existing employees, whereas Multiverse provides simultaneous employment and upskilling via employer apprenticeships. Companies like Interplay Learning and MT Copeland respectively develop and deliver curricula for the skilled construction trades via VR simulations and online course content. Other companies in this category focus on the financing piece of skills training and develop tailored financing products or distribution channels to help potential workers access and pay for skilled trades programs. Fynn, for example, provides loan financing specifically for students looking to enroll in trade schools. Finally, another approach to creating new labor supply is bringing the employer directly into the education and education financing process. UpSmith does this by enabling employers to sponsor the training of sourced and vetted job candidates in the skilled trades.

This model works best for in-demand professions that have relatively consistent expected earning potential. This helps providers justify the cost of developing and providing these training programs. Certain skilled trade professions (electrical, HVAC, plumbing, etc.) are particularly well-suited to this model for two reasons. First, these professions typically only require two or less years of formal classroom instruction time, making learning modules more self-contained and easier to develop, deliver, or license. Second, these professions require a relatively uniform set of skills across employers, so curricula are more scalable and do not need to be bespoke. This category of workforce development operates on a medium time horizon and can address workforce challenges in about the same amount of time it takes for a potential worker to earn a credential.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Building new employers

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The rarest and perhaps most non-intuitive approach to building a workforce development company is to focus on the demand for labor. This approach typically involves building new employers in an industry by creating new technology that redefines the jobs in question, while owning more of the training process in house.

There are two intertwining theories behind this model. First is that building more advanced tools, often with some degree of automation, lowers the barriers to entry for the profession. For example, if a tool allows for 80% of a job to be automated, the skill barrier for performing the remaining 20% becomes much lower. As such, those job candidates can be sourced from a much wider variety of backgrounds and trained on the job in house. Hadrian has taken this approach, as it develops a new generation of machinists for the defense and aerospace industrial base. Building better internal tools and systems — both software and hardware — also helps address the labor shortage by altering the demand side (the job itself) and acting as the employer.

Second, this model relies on the theory that insourcing the educational parts of the education-to-employment pipeline enables companies to deploy and iterate on the new tools for their workforces faster and more frequently. This often reduces barriers to entry, as candidates are trained specifically to use these systems and technologies. Furthermore, education and employment in this model are very well aligned, given that the enrollment in these programs can be completely determined by the employer’s hiring needs. This insourcing could look like an employer sourcing their employees from an internal trade school that prepares them for various jobs at the company. For example, Forge is a construction company that brings the trade school it needs to staff its operations in house; the graduates then become apprentices at the company. Bringing training in house also complements the building new tools model mentioned above, as employers can train employees on company-specific technologies and systems. Single employers building in-house schools to teach — and then employ — employees is not without precedent. Kettering University, formerly known as the General Motors Institute, trained automotive talent to work at GM via a co-op model.

We believe there are two opportunities to build here. First, building net-new employers in industries like advanced manufacturing and construction allows these workforce-intensive businesses to hire more broadly, as they can specifically tailor their employee training programs to their hiring needs and internal systems. Second, there is an opportunity for companies to build the picks and shovels that enable the long tail of businesses. As building educational programs solely for one employer is only a viable solution for the GMs and Amazons of the world, smaller employers — for instance, those in the construction trades — can benefit from having a third-party service build comparable programs for their employees.

This approach to the workforce development category takes the longest to realize, but is, nevertheless, the most adept at solving labor shortages at a structural and generational level. This approach also helps tackle the cultural issues surrounding many of these professions, particularly those in the skilled trades. By building new technologies and new employers for these jobs, they will hopefully be once again culturally relevant and desired as a socially aspirational path for young people.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A Note on Automation

When discussing technology and the workforce, one can’t avoid the topic of automation. Automation simultaneously highlights the problems with — and potential solution for — America’s labor shortages and workforce challenges. For instance, industrial robots can do everything from assembly to machine tending in manufacturing, and everything from packaging to pick-and-place in logistics. Companies building automation-based solutions to workforce challenges tend to either create new labor supply, by solving labor shortages in fields that humans don’t want to do (e.g., jobs with inhospitable or undesirable working conditions), or they create new labor demand, as most automated systems still require some human oversight.

—

It would be naive to think that there are quick fixes for labor shortages across such a wide variety of industries and professions. The project of strengthening the American workforce is a generational one, and the problems we face in doing so require myriad solutions — including deploying new technology products and systems, new business models, and new forms of education. Furthermore, it requires founders and builders to revitalize the culture of these critical professions, that channel mimetic energies toward these productive ends. It requires us, ultimately, to build a culture of seriousness.

If you’re building a company that’s developing the American workforce or want to discuss your perspectives on the category, feel free to reach out to oliver@a16z.com.