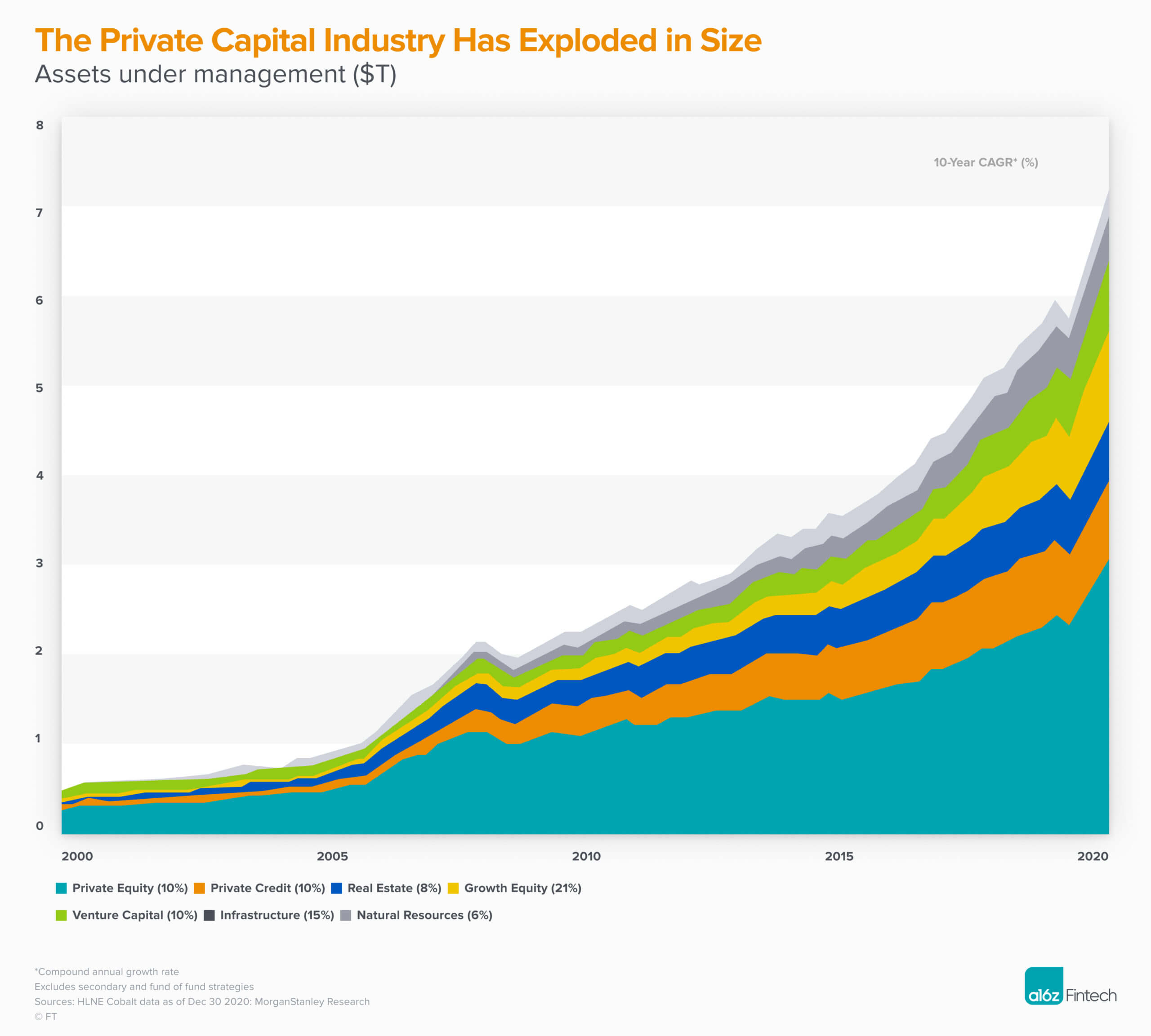

Over the past 20 years, there has been a dramatic shift in capital flow from the public to private markets. Since 2000, private market assets have grown over 10 times, representing over $6 trillion globally. This trend has been driven by a variety of factors, including low interest rates, companies staying private longer, the need for portfolio diversification, and the outperformance of private market asset classes over public market investments in recent years. As a result, we’ve seen significant institutional investor dollars flow into most major private market asset classes, including private equity, venture capital, real estate, infrastructure, and commodities.

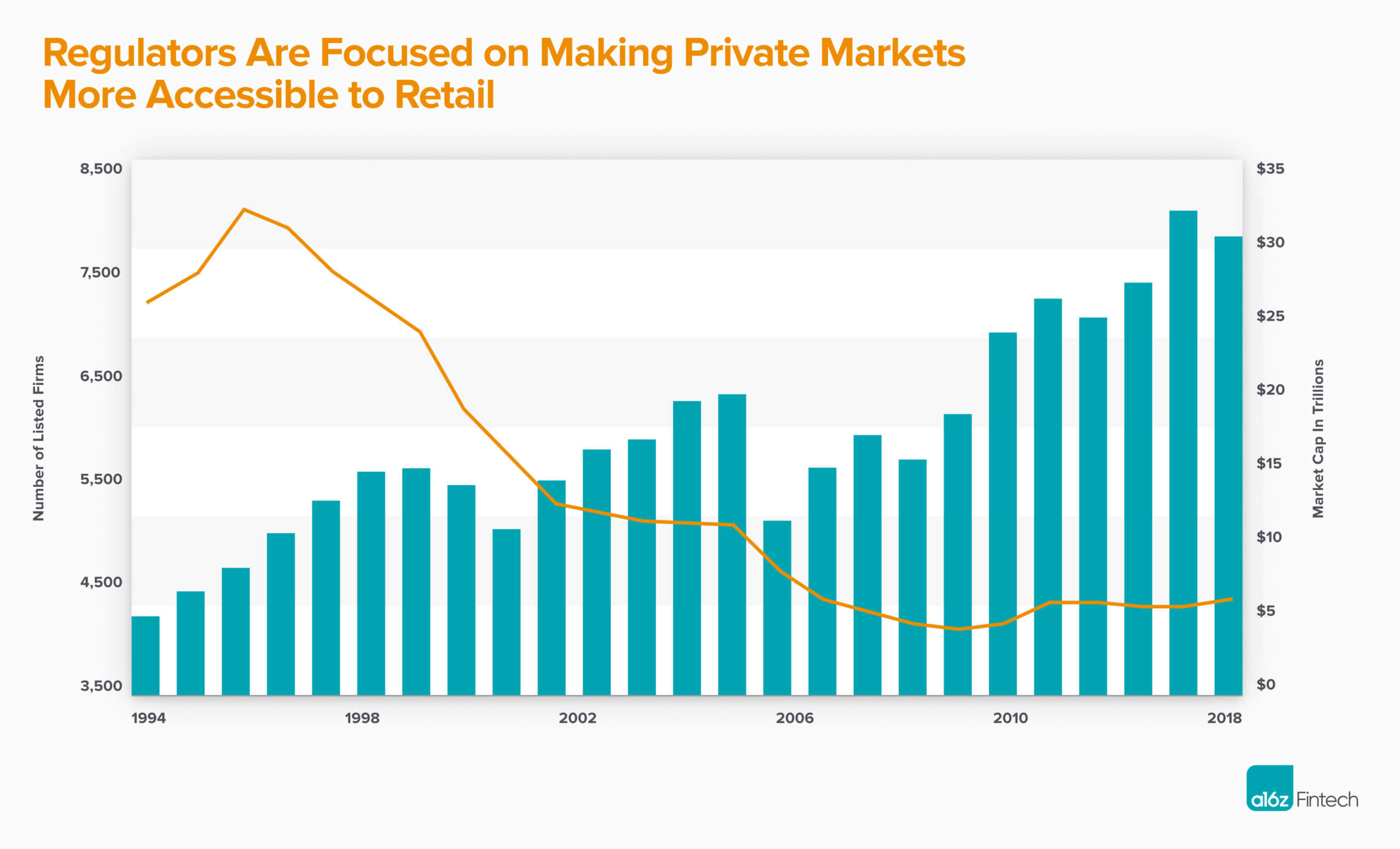

But while institutional investors have benefited from private market performance, retail investors have been largely left behind. With the decline in the number of public companies over the past two decades (in addition to companies staying private longer), much of the value creation has happened outside of retail investor portfolios.

Regulators are now focused on expanding retail access to the private markets, both through expanded accredited investor definitions and recent amendments to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), which makes it possible for retirement accounts to invest directly in private equity.

These changes could mean a new wave of retail capital may flow into the private markets in the coming years.

One of the secondary effects of so much capital in the private markets, especially from retail investors, will be a growing need for liquidity. While institutional investors also occasionally look to sell assets, the cash flow management needs of individual investors are typically far more acute.

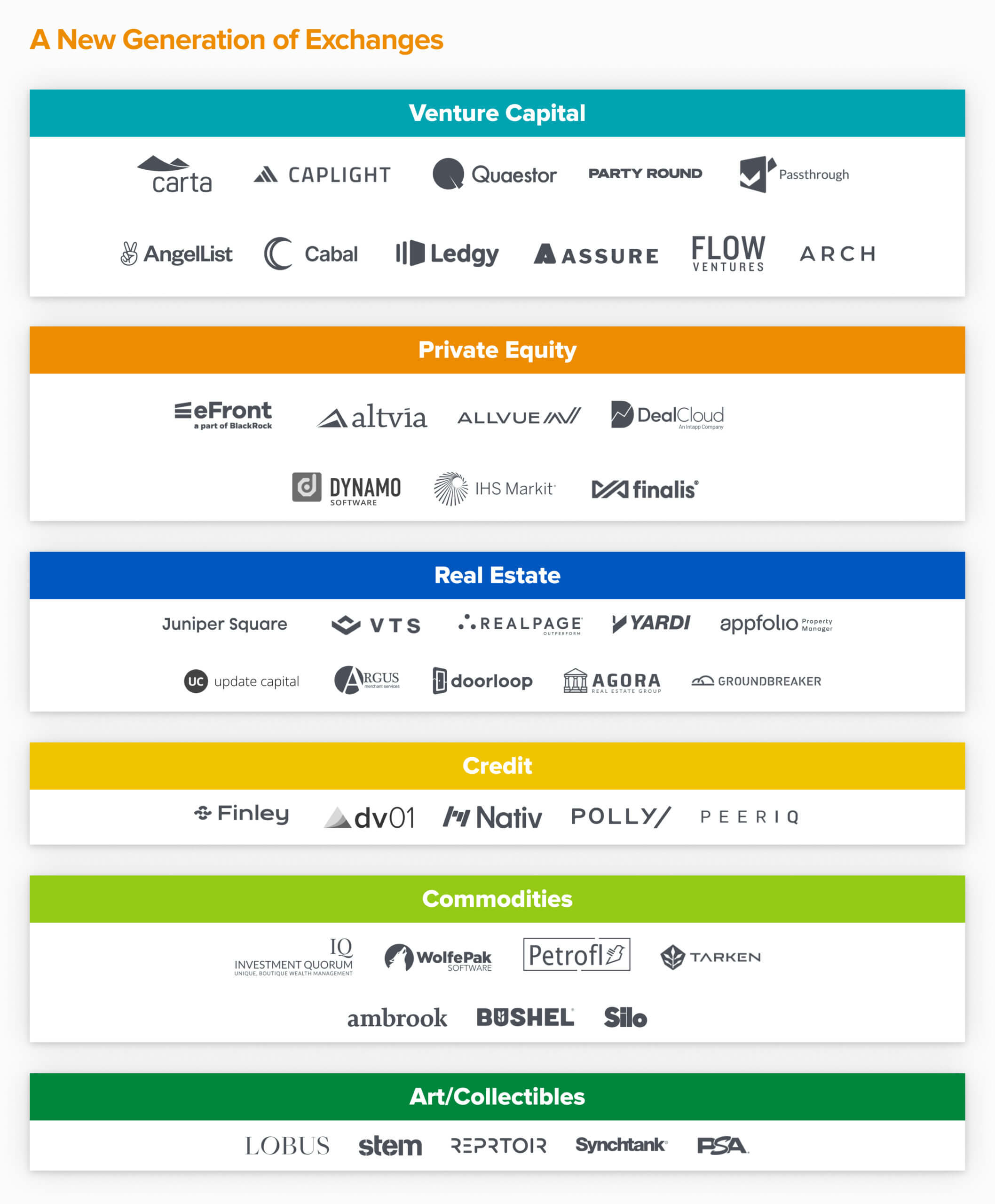

It’s likely we’ll see a new generation of private market exchanges formed to meet this growing need for liquidity — and that they will begin as software.

I call this strategy “Come for the Tool, Stay for the Exchange.” (It’s a fintech-focused update on Chris Dixon’s “Come for the tool, stay for the network.”) Entrepreneurs who employ it will be able to more effectively bootstrap buyers and sellers, avoid negative selection of market participants, and ensure common standards for financial reporting (which are typically lacking in the private markets) — all of which can help reinforce a more durable venue for liquidity.

Tackling the Investor Relations Stack

What does “Come for the Tool” mean? Ultimately, a private market exchange needs to overcome two key challenges: 1) Standardized financial information across the assets being traded, and 2) A two-sided network of buyers and sellers.

Unlike the public markets, the private markets lack a regulatory mandate for publishing standardized financial information. There is no SEC to enforce 10-Ks or Qs, or FINRA to require that bond prices be published via TRACE. As a result, private market data remains heterogeneous and opaque, two qualities antithetical to building liquidity in an exchange.

Furthermore, attempts at building private exchanges have typically started as the exchange itself. In these cases, entrepreneurs face a classic “cold start” problem in that it can be incredibly difficult to bootstrap sufficient liquidity of buyers and sellers on both sides of the network. Worse, these venues often face negative selection in the types of market participants willing to transact, since the best companies and investors don’t typically need or want to tap a nascent exchange for access to capital.

In contrast, the best companies and the best investors will always want to use the best tools. By solving one of the many manual, back-office workflows with software, you can enforce standardized financial reporting and more effectively aggregate quality supply in the network.

Carta provides one example of a company executing this “Come for the Tool, Stay for the Exchange” strategy. (Full disclosure: a16z is an investor.) The company started by solving cap table management, building software that acts as a common ledger of ownership between companies, employees, and investors. By achieving distribution among startups with its cap table product, Carta could also deliver capabilities like portfolio analytics and reporting, fund administration, and banking products like capital call facilities to the other side of its network: venture capital investors.

In doing so, Carta unlocked a two-sided network. The company ultimately applied to become an Alternative Trading System (ATS) and built exchange technology for its CartaX product, which allows late-stage private companies to programmatically sell secondary stakes in their businesses.

Similarly, Juniper Square built a system of record for real estate private equity GPs to run their businesses on top of, encompassing everything from subscription doc management and CRM to fund accounting and administration, portfolio reporting and analytics, and banking products like payments. Eventually, I believe it’s inevitable that Juniper Square will begin to serve the other side of its network, LPs, by giving them the ability to track all of their real estate exposure across managers and at the asset level.

With a two-sided network in place, and, importantly, standardized financial information on both sides, Juniper Square would have a compelling opportunity to unlock a powerful capital markets business and launch an exchange. The company could help managers sell individual properties among each other, for example, or secondary fund interests to LPs.

Considering these examples and many others, I believe that investor relations is a unique beachhead for building the future of private market exchanges.

- Banking, payments, and treasury management: Financial infrastructure is at the lowest level of the investor relations stack. Providing banking, payments, and treasury management services to companies or investors can be a clever way to onboard users and control or standardize the most basic level of financial information — the inflows and outflows of capital.

- Asset monitoring and accounting: It’s critical to provide tools to monitor and account for asset-level or fund-level cash flows and financial performance. Integrations into third-party software like loan servicing systems, rental-payment infrastructure, or other tools that gather financial information at the source are beneficial. This layer may also include service-like offerings such as fund administration, which can decrease the friction of onboarding to new infrastructure and drive increased retention to the platform.

- Legal documentation and client management: The ability to onboard and manage new investors is core to investor relations. Tools such as cap table management software serve as a general ledger for tracking ownership between a company, its employees, and its investors. Similarly, software to streamline onboarding new LPs with subscription documents can also be useful. Lastly, customer relationship management functionality can unify workflows into a common system, rather than being spread across multiple tools. Importantly, each of these actions can effectively pull new counterparties into a “network.”

- Performance reporting and analytics: Ultimately, investors expect a return on their investments and want an easy way to monitor their investment’s performance. A common dashboard to track one’s holdings or be able to drill down at the fund or asset level is valuable. This activity can fuel a network effect for investor relations software.

The various layers of the Investor Relations Stack can also work in concert with one another, enabling workflows to be built on top of each other. Together, these make up a system of record through which a company or investment firm can run their back office.

From venture capital to private equity, real estate to credit, and commodities to collectibles, amazing companies are solving tedious investor relations workflows with beautiful software. Their tools are standardizing financial reporting and aggregating leading companies and investors across all major private market asset classes. While many of these companies don’t yet view themselves as exchanges, many of them are well positioned to build durable venues for private market liquidity. Those that successfully execute against this opportunity have the potential to unlock a tremendous amount of enterprise value.