Large language models are a powerful new primitive for building software. But since they are so new—and behave so differently from normal computing resources—it’s not always obvious how to use them.

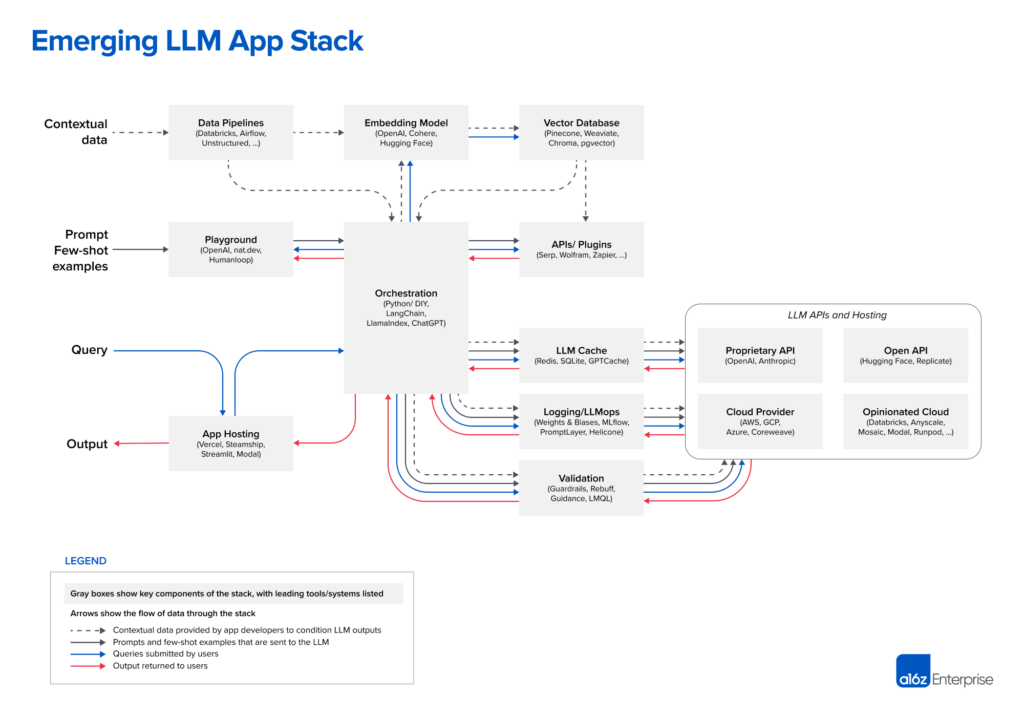

In this post, we’re sharing a reference architecture for the emerging LLM app stack. It shows the most common systems, tools, and design patterns we’ve seen used by AI startups and sophisticated tech companies. This stack is still very early and may change substantially as the underlying technology advances, but we hope it will be a useful reference for developers working with LLMs now.

This work is based on conversations with AI startup founders and engineers. We relied especially on input from: Ted Benson, Harrison Chase, Ben Firshman, Ali Ghodsi, Raza Habib, Andrej Karpathy, Greg Kogan, Jerry Liu, Moin Nadeem, Diego Oppenheimer, Shreya Rajpal, Ion Stoica, Dennis Xu, Matei Zaharia, and Jared Zoneraich. Thank you for your help!

Note: A living and more comprehensive version of these components is available in our LLM App Stack repo on GitHub.

The stack

Here’s our current view of the LLM app stack (click to enlarge):

And here’s a list of links to each project for quick reference:

| Data pipelines | Embedding model | Vector database | Playground | Orchestration | APIs/plugins | LLM cache |

| Databricks | OpenAI | Pinecone | OpenAI | Langchain | Serp | Redis |

| Airflow | Cohere | Weaviate | nat.dev | LlamaIndex | Wolfram | SQLite |

| Unstructured | Hugging Face | ChromaDB | Humanloop | ChatGPT | Zapier | GPTCache |

| pgvector |

| Logging / LLMops | Validation | App hosting | LLM APIs (proprietary) | LLM APIs (open) | Cloud providers | Opinionated clouds |

| Weights & Biases | Guardrails | Vercel | OpenAI | Hugging Face | AWS | Databricks |

| MLflow | Rebuff | Steamship | Anthropic | Replicate | GCP | Anyscale |

| PromptLayer | Microsoft Guidance | Streamlit | Azure | Mosaic | ||

| Helicone | LMQL | Modal | CoreWeave | Modal | ||

| RunPod |

There are many different ways to build with LLMs, including training models from scratch, fine-tuning open-source models, or using hosted APIs. The stack we’re showing here is based on in-context learning, which is the design pattern we’ve seen the majority of developers start with (and is only possible now with foundation models).

The next section gives a brief explanation of this pattern; experienced LLM developers can skip this section.

Design pattern: In-context learning

The core idea of in-context learning is to use LLMs off the shelf (i.e., without any fine-tuning), then control their behavior through clever prompting and conditioning on private “contextual” data.

For example, say you’re building a chatbot to answer questions about a set of legal documents. Taking a naive approach, you could paste all the documents into a ChatGPT or GPT-4 prompt, then ask a question about them at the end. This may work for very small datasets, but it doesn’t scale. The biggest GPT-4 model can only process ~50 pages of input text, and performance (measured by inference time and accuracy) degrades badly as you approach this limit, called a context window.

In-context learning solves this problem with a clever trick: instead of sending all the documents with each LLM prompt, it sends only a handful of the most relevant documents. And the most relevant documents are determined with the help of . . . you guessed it . . . LLMs.

At a very high level, the workflow can be divided into three stages:

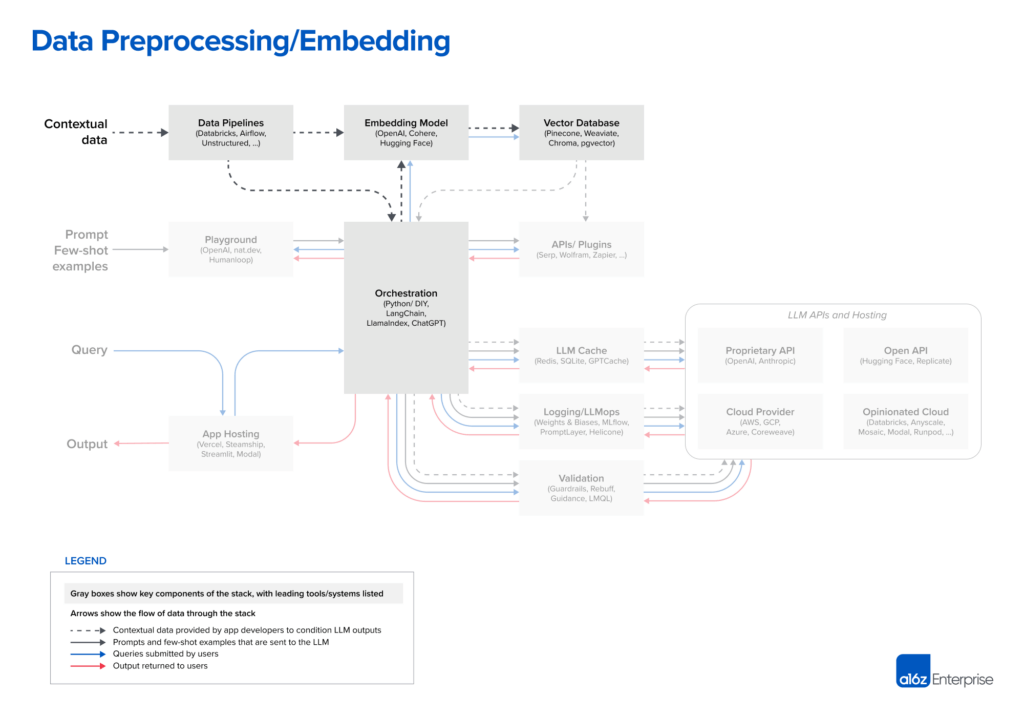

- Data preprocessing / embedding: This stage involves storing private data (legal documents, in our example) to be retrieved later. Typically, the documents are broken into chunks, passed through an embedding model, then stored in a specialized database called a vector database.

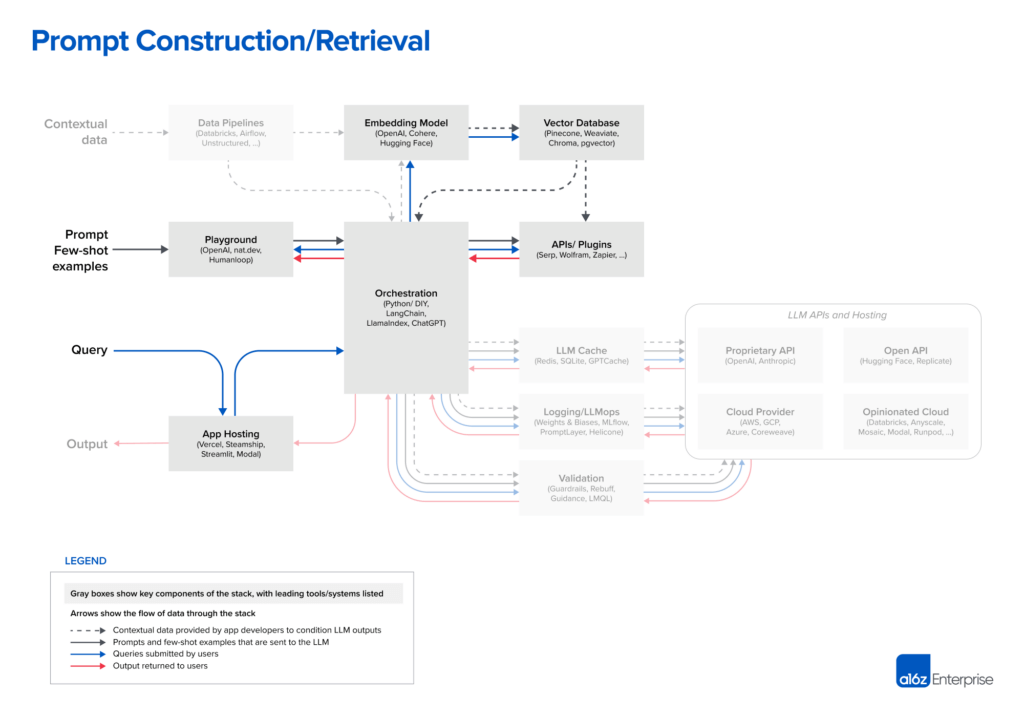

- Prompt construction / retrieval: When a user submits a query (a legal question, in this case), the application constructs a series of prompts to submit to the language model. A compiled prompt typically combines a prompt template hard-coded by the developer; examples of valid outputs called few-shot examples; any necessary information retrieved from external APIs; and a set of relevant documents retrieved from the vector database.

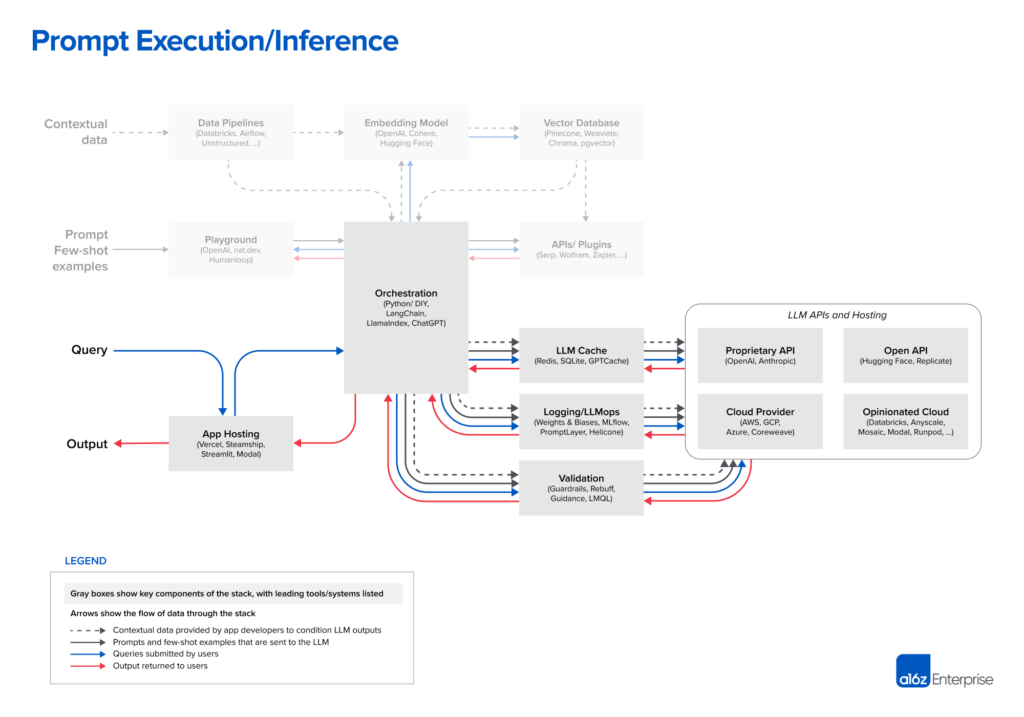

- Prompt execution / inference: Once the prompts have been compiled, they are submitted to a pre-trained LLM for inference—including both proprietary model APIs and open-source or self-trained models. Some developers also add operational systems like logging, caching, and validation at this stage.

This looks like a lot of work, but it’s usually easier than the alternative: training or fine-tuning the LLM itself. You don’t need a specialized team of ML engineers to do in-context learning. You also don’t need to host your own infrastructure or buy an expensive dedicated instance from OpenAI. This pattern effectively reduces an AI problem to a data engineering problem that most startups and big companies already know how to solve. It also tends to outperform fine-tuning for relatively small datasets—since a specific piece of information needs to occur at least ~10 times in the training set before an LLM will remember it through fine-tuning—and can incorporate new data in near real time.

One of the biggest questions around in-context learning is: What happens if we just change the underlying model to increase the context window? This is indeed possible, and it is an active area of research (e.g., see the Hyena paper or this recent post). But this comes with a number of tradeoffs—primarily that cost and time of inference scale quadratically with the length of the prompt. Today, even linear scaling (the best theoretical outcome) would be cost-prohibitive for many applications. A single GPT-4 query over 10,000 pages would cost hundreds of dollars at current API rates. So, we don’t expect wholesale changes to the stack based on expanded context windows, but we’ll comment on this more in the body of the post.

If you’d like to go deeper on in-context learning, there are a number of great resources in the AI canon (especially the “Practical guides to building with LLMs” section). In the remainder of this post, we’ll walk through the reference stack, using the workflow above as a guide.

Contextual data for LLM apps includes text documents, PDFs, and even structured formats like CSV or SQL tables. Data-loading and transformation solutions for this data vary widely across developers we spoke with. Most use traditional ETL tools like Databricks or Airflow. Some also use document loaders built into orchestration frameworks like LangChain (powered by Unstructured) and LlamaIndex (powered by Llama Hub). We believe this piece of the stack is relatively underdeveloped, though, and there’s an opportunity for data-replication solutions purpose-built for LLM apps.

For embeddings, most developers use the OpenAI API, specifically with the text-embedding-ada-002 model. It’s easy to use (especially if you’re already already using other OpenAI APIs), gives reasonably good results, and is becoming increasingly cheap. Some larger enterprises are also exploring Cohere, which focuses their product efforts more narrowly on embeddings and has better performance in certain scenarios. For developers who prefer open-source, the Sentence Transformers library from Hugging Face is a standard. It’s also possible to create different types of embeddings tailored to different use cases; this is a niche practice today but a promising area of research.

The most important piece of the preprocessing pipeline, from a systems standpoint, is the vector database. It’s responsible for efficiently storing, comparing, and retrieving up to billions of embeddings (i.e., vectors). The most common choice we’ve seen in the market is Pinecone. It’s the default because it’s fully cloud-hosted—so it’s easy to get started with—and has many of the features larger enterprises need in production (e.g., good performance at scale, SSO, and uptime SLAs).

There’s a huge range of vector databases available, though. Notably:

- Open source systems like Weaviate, Vespa, and Qdrant: They generally give excellent single-node performance and can be tailored for specific applications, so they are popular with experienced AI teams who prefer to build bespoke platforms.

- Local vector management libraries like Chroma and Faiss: They have great developer experience and are easy to spin up for small apps and dev experiments. They don’t necessarily substitute for a full database at scale.

- OLTP extensions like pgvector: For devs who see every database-shaped hole and try to insert Postgres—or enterprises who buy most of their data infrastructure from a single cloud provider—this is a good solution for vector support. It’s not clear, in the long run, if it makes sense to tightly couple vector and scalar workloads.

Looking ahead, most of the open source vector database companies are developing cloud offerings. Our research suggests achieving strong performance in the cloud, across a broad design space of possible use cases, is a very hard problem. Therefore, the option set may not change massively in the near term, but it likely will change in the long term. The key question is whether vector databases will resemble their OLTP and OLAP counterparts, consolidating around one or two popular systems.

Another open question is how embeddings and vector databases will evolve as the usable context window grows for most models. It’s tempting to say embeddings will become less relevant, because contextual data can just be dropped into the prompt directly. However, feedback from experts on this topic suggests the opposite—that the embedding pipeline may become more important over time. Large context windows are a powerful tool, but they also entail significant computational cost. So making efficient use of them becomes a priority. We may start to see different types of embedding models become popular, trained directly for model relevancy, and vector databases designed to enable and take advantage of this.

Strategies for prompting LLMs and incorporating contextual data are becoming increasingly complex—and increasingly important as a source of product differentiation. Most developers start new projects by experimenting with simple prompts, consisting of direct instructions (zero-shot prompting) or possibly some example outputs (few-shot prompting). These prompts often give good results but fall short of accuracy levels required for production deployments.

The next level of prompting jiu jitsu is designed to ground model responses in some source of truth and provide external context the model wasn’t trained on. The Prompt Engineering Guide catalogs no fewer than 12 (!) more advanced prompting strategies, including chain-of-thought, self-consistency, generated knowledge, tree of thoughts, directional stimulus, and many others. These strategies can also be used in conjunction to support different LLM use cases like document question answering, chatbots, etc.

This is where orchestration frameworks like LangChain and LlamaIndex shine. They abstract away many of the details of prompt chaining; interfacing with external APIs (including determining when an API call is needed); retrieving contextual data from vector databases; and maintaining memory across multiple LLM calls. They also provide templates for many of the common applications mentioned above. Their output is a prompt, or series of prompts, to submit to a language model. These frameworks are widely used among hobbyists and startups looking to get an app off the ground, with LangChain the leader.

LangChain is still a relatively new project (currently on version 0.0.201), but we’re already starting to see apps built with it moving into production. Some developers, especially early adopters of LLMs, prefer to switch to raw Python in production to eliminate an added dependency. But we expect this DIY approach to decline over time for most use cases, in a similar way to the traditional web app stack.

Sharp-eyed readers will notice a seemingly weird entry in the orchestration box: ChatGPT. In its normal incarnation, ChatGPT is an app, not a developer tool. But it can also be accessed as an API. And, if you squint, it performs some of the same functions as other orchestration frameworks, such as: abstracting away the need for bespoke prompts; maintaining state; and retrieving contextual data via plugins, APIs, or other sources. While not a direct competitor to the other tools listed here, ChatGPT can be considered a substitute solution, and it may eventually become a viable, simple alternative to prompt construction.

Today, OpenAI is the leader among language models. Nearly every developer we spoke with starts new LLM apps using the OpenAI API, usually with the gpt-4 or gpt-4-32k model. This gives a best-case scenario for app performance and is easy to use, in that it operates on a wide range of input domains and usually requires no fine-tuning or self-hosting.

When projects go into production and start to scale, a broader set of options come into play. Some of the common ones we heard include:

- Switching to gpt-3.5-turbo: It’s ~50x cheaper and significantly faster than GPT-4. Many apps don’t need GPT-4-level accuracy, but do require low latency inference and cost effective support for free users.

- Experimenting with other proprietary vendors (especially Anthropic’s Claude models): Claude offers fast inference, GPT-3.5-level accuracy, more customization options for large customers, and up to a 100k context window (though we’ve found accuracy degrades with the length of input).

- Triaging some requests to open source models: This can be especially effective in high-volume B2C use cases like search or chat, where there’s wide variance in query complexity and a need to serve free users cheaply.

- This usually makes the most sense in conjunction with fine-tuning open source base models. We don’t go deep on that tooling stack in this article, but platforms like Databricks, Anyscale, Mosaic, Modal, and RunPod are used by a growing number of engineering teams.

- A variety of inference options are available for open source models, including simple API interfaces from Hugging Face and Replicate; raw compute resources from the major cloud providers; and more opinionated cloud offerings like those listed above.

Open-source models trail proprietary offerings right now, but the gap is starting to close. The LLaMa models from Meta set a new bar for open source accuracy and kicked off a flurry of variants. Since LLaMa was licensed for research use only, a number of new providers have stepped in to train alternative base models (e.g., Together, Mosaic, Falcon, Mistral). Meta is also debating a truly open source release of LLaMa 2.

When (not if) open source LLMs reach accuracy levels comparable to GPT-3.5, we expect to see a Stable Diffusion-like moment for text—including massive experimentation, sharing, and productionizing of fine-tuned models. Hosting companies like Replicate are already adding tooling to make these models easier for software developers to consume. There’s a growing belief among developers that smaller, fine-tuned models can reach state-of-the-art accuracy in narrow use cases.

Most developers we spoke with haven’t gone deep on operational tooling for LLMs yet. Caching is relatively common—usually based on Redis—because it improves application response times and cost. Tools like Weights & Biases and MLflow (ported from traditional machine learning) or PromptLayer and Helicone (purpose-built for LLMs) are also fairly widely used. They can log, track, and evaluate LLM outputs, usually for the purpose of improving prompt construction, tuning pipelines, or selecting models. There are also a number of new tools being developed to validate LLM outputs (e.g., Guardrails) or detect prompt injection attacks (e.g., Rebuff). Most of these operational tools encourage use of their own Python clients to make LLM calls, so it will be interesting to see how these solutions coexist over time.

Finally, the static portions of LLM apps (i.e. everything other than the model) also need to be hosted somewhere. The most common solutions we’ve seen so far are standard options like Vercel or the major cloud providers. However, two new categories are emerging. Startups like Steamship provide end-to-end hosting for LLM apps, including orchestration (LangChain), multi-tenant data contexts, async tasks, vector storage, and key management. And companies like Anyscale and Modal allow developers to host models and Python code in one place.

What about agents?

The most important components missing from this reference architecture are AI agent frameworks. AutoGPT, described as “an experimental open-source attempt to make GPT-4 fully autonomous,” was the fastest-growing Github repo in history this spring, and practically every AI project or startup out there today includes agents in some form.

Most developers we speak with are incredibly excited about the potential of agents. The in-context learning pattern we describe in this post is effective at solving hallucination and data-freshness problems, in order to better support content-generation tasks. Agents, on the other hand, give AI apps a fundamentally new set of capabilities: to solve complex problems, to act on the outside world, and to learn from experience post-deployment. They do this through a combination of advanced reasoning/planning, tool usage, and memory / recursion / self-reflection.

So, agents have the potential to become a central piece of the LLM app architecture (or even take over the whole stack, if you believe in recursive self-improvement). And existing frameworks like LangChain have incorporated some agent concepts already. There’s only one problem: agents don’t really work yet. Most agent frameworks today are in the proof-of-concept phase—capable of incredible demos but not yet reliable, reproducible task-completion. We’re keeping an eye on how they develop in the near future.

Looking ahead

Pre-trained AI models represent the most important architectural change in software since the internet. They make it possible for individual developers to build incredible AI apps, in a matter of days, that surpass supervised machine learning projects that took big teams months to build.

The tools and patterns we’ve laid out here are likely the starting point, not the end state, for integrating LLMs. We’ll update this as major changes take place (e.g., a shift toward model training) and release new reference architectures where it makes sense. Please reach out if you have any feedback or suggestions.