In our last deep-dive article on IPOs, we outlined how pricing works, how post-IPO activity is influenced by the four types of stock market investors, why the price of a marginal share is not that of a block trade, and how we shouldn’t throw the baby (IPOs) out with the bathwater (less-than-ideal price discovery), particularly for companies that need to raise a large amount of primary capital.

Since then, the debate over IPOs has continued, with a particular focus on allegedly underpriced offerings that jump shortly after opening — the dreaded “pop.” As some criticism has it, this supposedly deprives companies of millions of dollars that should have been theirs if not for underpricing the IPO.

What’s really going on and what, if anything, has changed? And why do the 2020 pops seem so different – in particular, much larger than we’ve seen before? Have bankers simply become even more evil in 2020, deliberately diverting more money from a company’s coffers to line the pockets of the buy-side institutional investors who subscribe to IPO shares?

In our last post, we showed that’s not happening, and since then an IPO with an auction (Unity) still showed a massive pop. But why would pops this year be different from those of years past? So in this post, we take a look at some historical data in an effort to better understand what’s really behind the IPO pop.

The tl;dr: It’s Economics 101. The laws of supply and demand, and marginal pricing, withstand the test of time.

There is nothing new under the sun

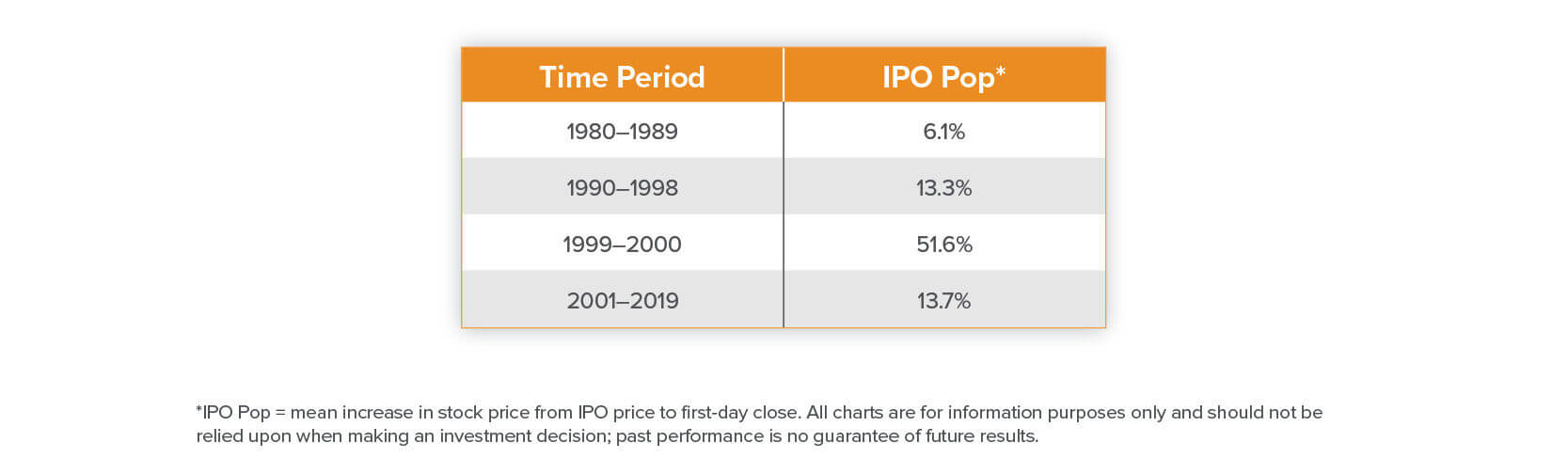

First, it’s important to point out that despite the evangelism of some against the traditional IPO, pops are nothing new:

A number of interesting things jump out from this data:

- IPO pops date back at least to the release of The Empire Strikes Back and the PacMan video game. (They probably pre-date those milestones, but this is the best dataset we could find!)

- The dot-com bubble was different in so many ways: record numbers of IPOs, record financial (im)maturity of IPO candidates, and record first-day IPO pops.

- The size of IPO pops doubled in the 1990-98 time frame vs the 1980s, ballooned in the dot-com bubble, and then reverted to the same levels over the past 20 years as they were in the pre-bubble nineties.

Demand matters: IPOs are a bull market product

Gauging demand for an IPO can be difficult, in part because so many IPO order books are over-subscribed. And no, that doesn’t mean that the IPO is underpriced; recall that there is no cost to putting in an “order” in the IPO book, so the incentive for the buy-side is to put in as large a request as possible with the understanding that they will ultimately be cut back by the underwriters. IPO “over-subscription” has also become a vanity metric for the bankers and the issuing company.

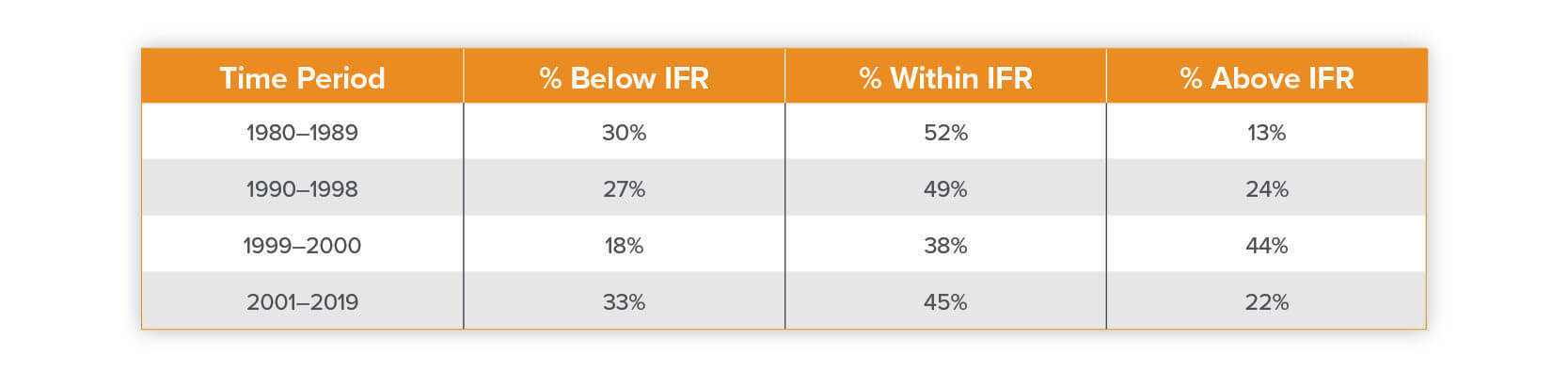

But there is one measure of observed financial behavior during the IPO process that provides a broad signal of demand (and a modicum of price elasticity). When a company files to go public, it provides an estimated range of the price at which it expects to sell its shares along with an estimated number of shares it expects to sell. This opening price range is often called the “initial filing range.” During the course of the roadshow that leads up to the final pricing of the IPO, the company may change the initial filing range (and/or the number of shares being issued in the offering) to reflect the indications of demand. More (or less) demand will cause the company to revise upward (or downward) its initial filing range before it ultimately picks a final offering price at which the IPO shares are sold to investors.

Thus, a rough proxy for the relative magnitude of the institutional demand is whether a company’s final offering price is above, within, or below its initial filing range. (Similarly, changes in the number of shares being offered would be another good proxy.)

What does this data tell us about the IPO cohorts?

- If we look at the percentage of IPOs that priced above the initial filing range (the far right column in the table), the 1980-89 time period has the lowest percentage. That is, about 87% of the IPOs in that cohort priced within or below the initial filing range, but only 13% priced above.

- Once again, the 1999-2000 dot-com bubble period shows the highest percentage of pricing above the initial filing range – 44% of deals were priced above. That of course comports with what we know about that era – very strong (some might say, “irrationally exuberant”) demand for IPOs.

- Interestingly the data for the 1990-98 and 2001-19 time periods are roughly the same – approximately one-quarter of deals priced above the initial filing range.

- Taken together, we can hypothesize that overall investor demand for IPOs was weaker in 1980-1989, in the middle in 1990-98 and again in 2001-2019, and highest in the dot-com bubble.

To be fair, we don’t know for certain that the behavior of bankers in setting the initial filing range didn’t change over these time periods and therefore skew the resulting data. For example, maybe bankers were just really aggressive in setting the initial filing range in the 1980-1989 time period and thus the lower percentage of above-range pricings simply reflects different pricing behavior versus other time periods. While we can’t know this one way or the other, rational behavior over decades of pricing deals suggests that the profit-maximizing strategy is to set the price lower at the initial filing range to generate demand (and minimize any concerns around valuation) and then benefit from the increased demand to walk-up the price over the course of the marketing process.

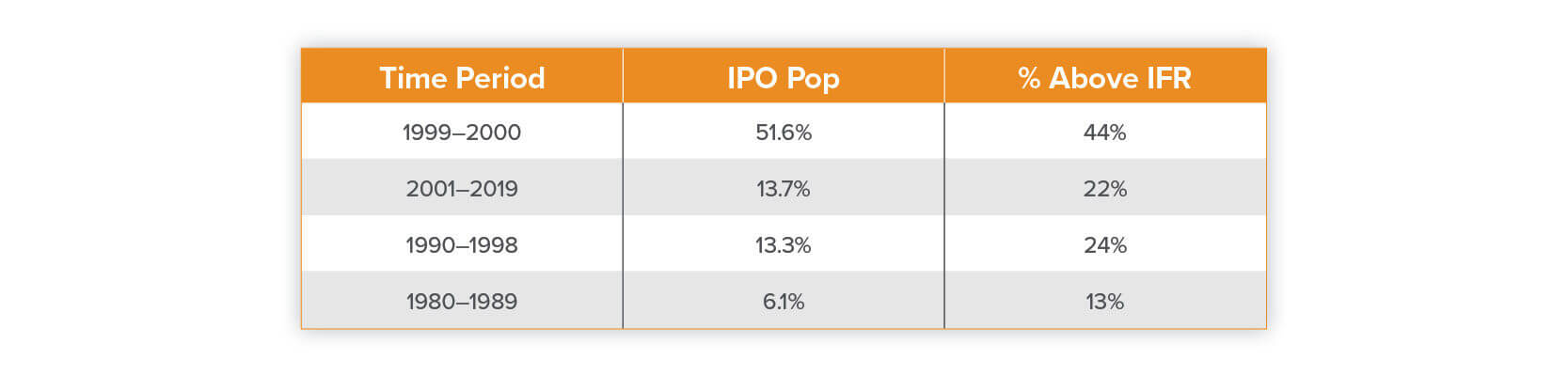

So, what happens when we combine the data from the two charts? To make things more readable, let’s focus just on the percentage of IPOs that priced above the initial filing range as our proxy for relative demand. And let’s order the time periods from highest to lowest IPO pop:

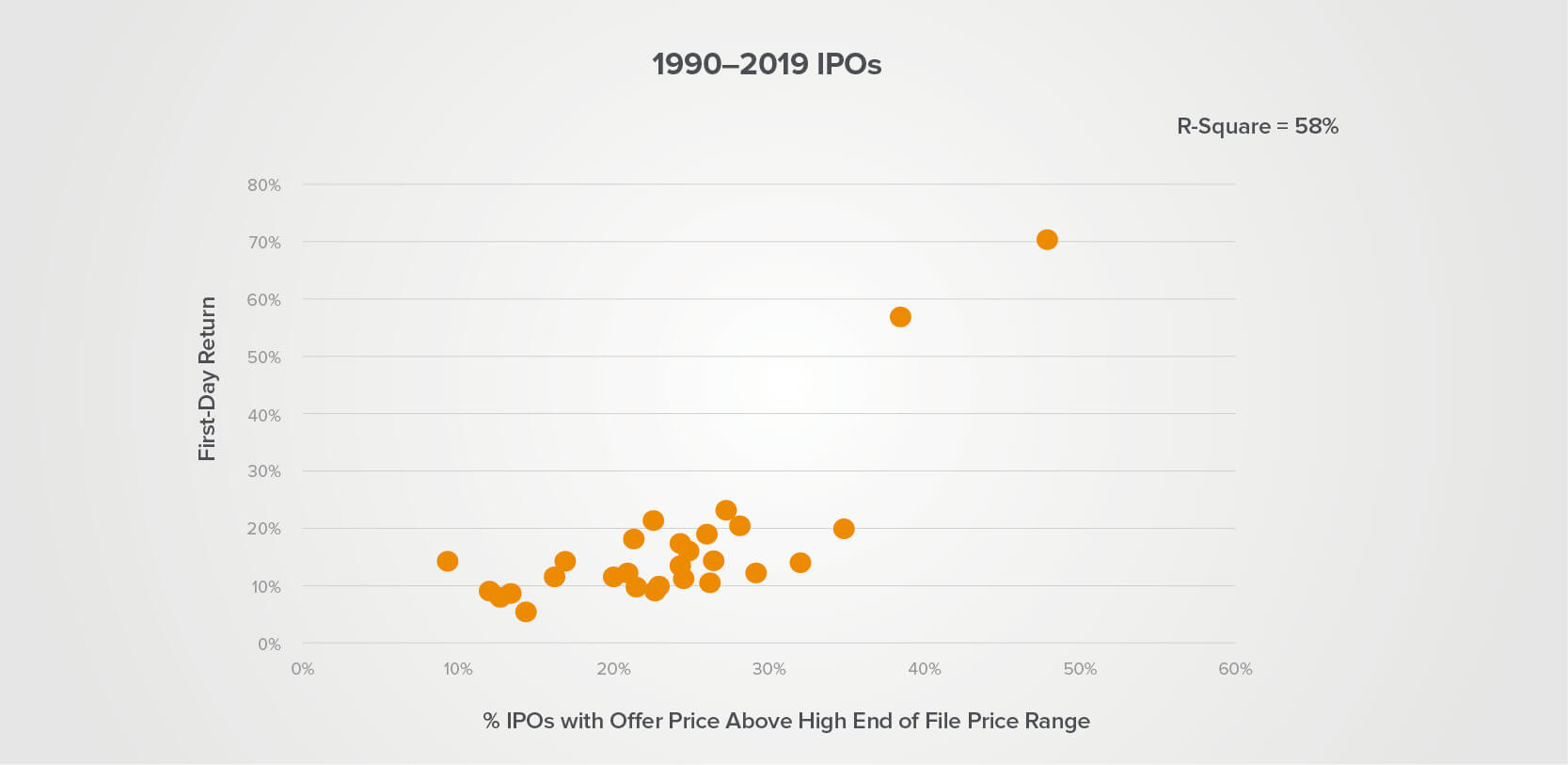

As we can see from the chart, our proxy for demand – the percentage of IPOs that priced above the initial filing range – seems directionally correlated with the size of the IPO pop. This is not a regression analysis — and remember, correlation does not equal causation — but there is a logical symmetry to what the data show. If you plot the individual years between 1990-2019, though, you see a fairly strong correlation (r-square = 58%) between percentage of IPOs pricing above the high end of the file range and the average first-day return.

If, as we suggested in our prior blog post, IPO pops are more likely a symptom of low floats and imperfect price discovery during IPO pricing (rather than a symptom of nefarious collusion between underwriters and the buy-side), and if we are trying to intuit the price at which the marginal buyer of a share post-IPO will purchase in the open market, the correlation makes sense. Bankers increase the final offering price relative to the initial filing range more frequently when they assess greater institutional demand during the roadshow, and, at the same time, the buy-side likely gets lower than their desired allocations in a “hot” IPO. The combination of these two factors would create stronger after-market performance, as the marginal buyers increase their ownership (and the momentum investors chase the price performance). Thus, a higher IPO pop.

Back to the future

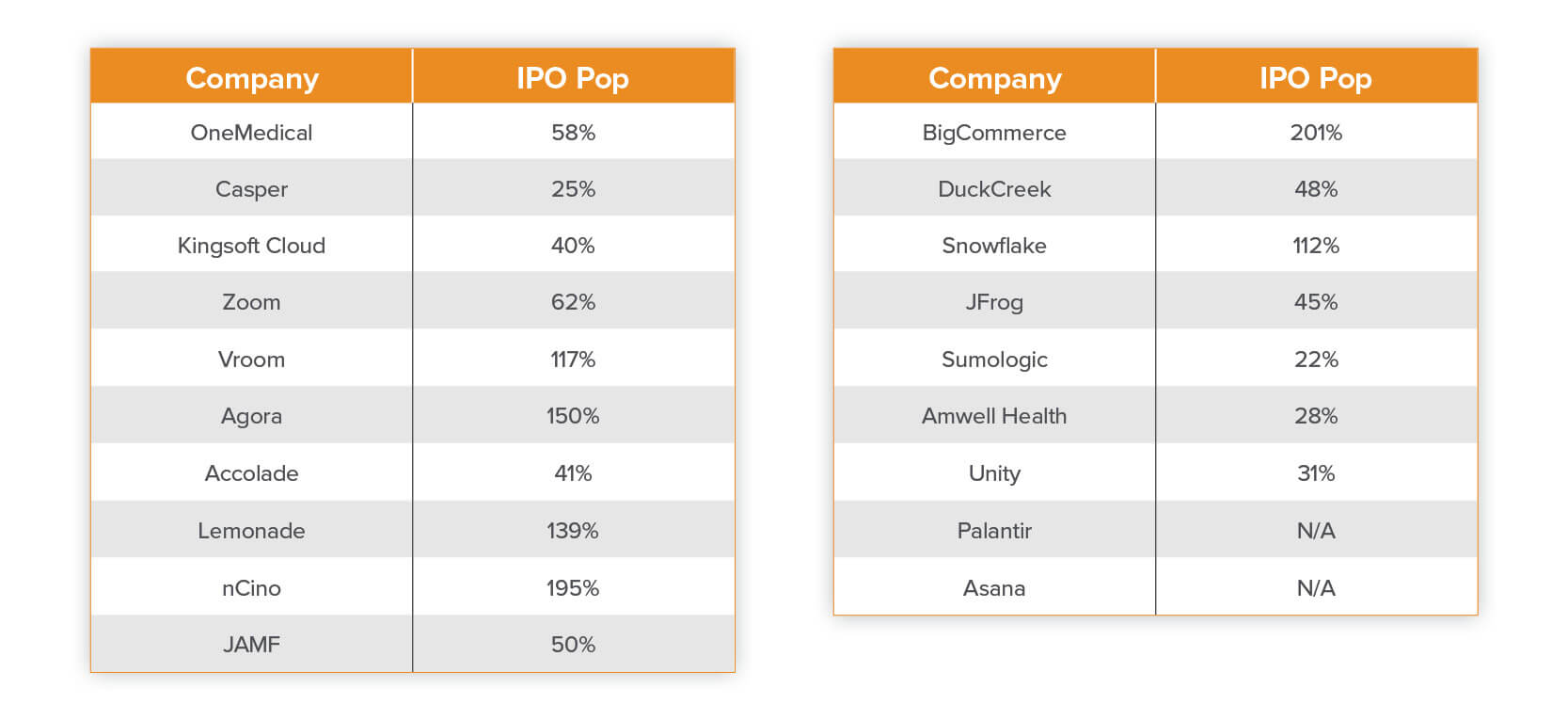

So what does any of this have to do with 2020? Well, let’s take a look at what has happened in the IPO market to create higher-than-historical IPO pops. We had to do some more manual data collection here, so to preserve our sanity we are focusing on tech IPOs through September 30 of this year, via Crunchbase:

Those are some big pops, particularly by historical standards – more in line with the dot-com bubble data than any other time period over the last 40 years. So what do we make of this?

First let’s incorporate the final-offer-price-to-filing-range-demand proxy that we discussed previously. With the exception of OneMedical (which priced its IPO within its initial filing range) and Casper (which priced below its initial filing range), every IPO priced above its initial filing range. That’s 88% of the deals pricing above the initial filing range, double the dot-com period data and 4x that of the other two closest time periods. (Note – we included Palantir and Asana for completeness on this list, but they were direct listings for which the concept of IPO pops and filing range adjustments doesn’t apply.) Casper had the second lowest IPO pop – after revising downward its pricing range – and has traded the worst of the group in the after-market. Combining that with the very high above-filing-range percentage of the other IPOs, again we see a consistent correlation between pricing range and magnitude of the pop.

So if we posit that higher demand for IPOs is causing higher IPO pops, what would explain the higher demand for IPOs? We are not taking a position on bubble vs. no-bubble, but there are a number of logical explanations for the shift in the demand curve:

- Interest rates. We are living in an unprecedented time of monetary policy where real yields are effectively zero and the Fed has all but committed to keeping rates low for a very long period of time. More importantly, the Fed has also signaled that perhaps our long-held views on the natural level of unemployment have been too high, meaning that the Fed is likely to keep interest rates lower for longer periods of time even when it suspects that wage inflation may be creeping up. The implications of this for asset managers is that they need to find yield (aka, investment returns) elsewhere. Thus, they shift more of their allocations to what they perceive as higher yielding assets such as equity securities. Higher demand for equities therefore drives higher prices of equities.

- Covid and the tech trade. Through September 30, Nasdaq (representing the tech trade) has significantly outperformed the S&P 500 (representing a more diversified tech and non-tech basket of companies). There is lots of speculation around this, ranging from a repeat of the point above (that tech assets are traditionally growth assets and thus should return higher yields in an environment where investors are seeking high-yielding assets) to the view that Covid has significantly accelerated the “software is eating the world” trend. If the future is coming faster, and tech is a maker and beneficiary of that future, then investors might bid up those assets because they believe they have the chance to generate higher and nearer-term cash flows.

- Scarcity of IPOs. Putting aside for now the hot topic of Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicles, or SPACs (which account for about 40% of IPOs this year), we are still experiencing historically low levels of tech IPOs. As the table above illustrates, we’ve had 19 tech IPOs this year (albeit with a heavy forward calendar yet to come). That compares with an average of roughly 35 per year over the last twenty years and pales in comparison to the roughly 100 per year from 1980 leading up to the dot-com bubble. Again, high demand coupled with low supply is a recipe for higher price movements.

- Scarcity of float. Compounding the small number of IPOs this year is the small percentage of company shares that are being sold in the offerings. This is often called the IPO float, and it reflects the quotient of the number of shares sold in the offering divided by the total shares outstanding for the company. Traditionally, companies would have a post-IPO float of about 25-40%; in the 2020 class, the median float is 15.5%. Moreover, the “higher quality” the company, the less money it often needs to raise (reducing the number of shares it wants to offer) and the more demand for its shares (pushing up the initial price), which makes some of the top “poppers” the lowest “floaters.” It’s another reason IPO prices often rise — to offset a limited supply with very high demand (more on this below).

By the way, back to Unity, which seemed to defy expectations. This is a company that innovated on the traditional IPO process by having the buyside submit not just their share requests but also their demand for shares at different price points. Effectively, Unity was trying to model out the demand curve for its IPO shares. The company also asserted greater control over the allocation process – deciding which investors got how many shares – a process often relegated to the underwriting bank, and increased its float by allowing secondary selling on day one (employees, former employees, executives and directors could sell 15% of shares on open).

While Unity didn’t eliminate the IPO pop, it is interesting to observe that the magnitude of its IPO pop was on the much lower end relative to the broader 2020 class. Another data point suggesting that better price discovery and variable first day supply can impact IPO pops.

Floats

Let’s dive a little deeper into the topic of floats since it is one of the IPO variables that has changed significantly over time.

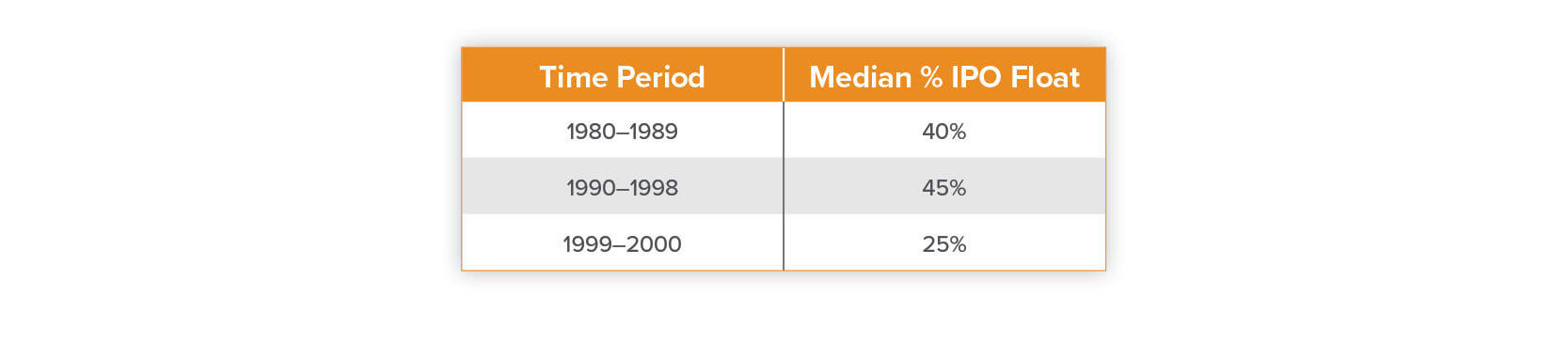

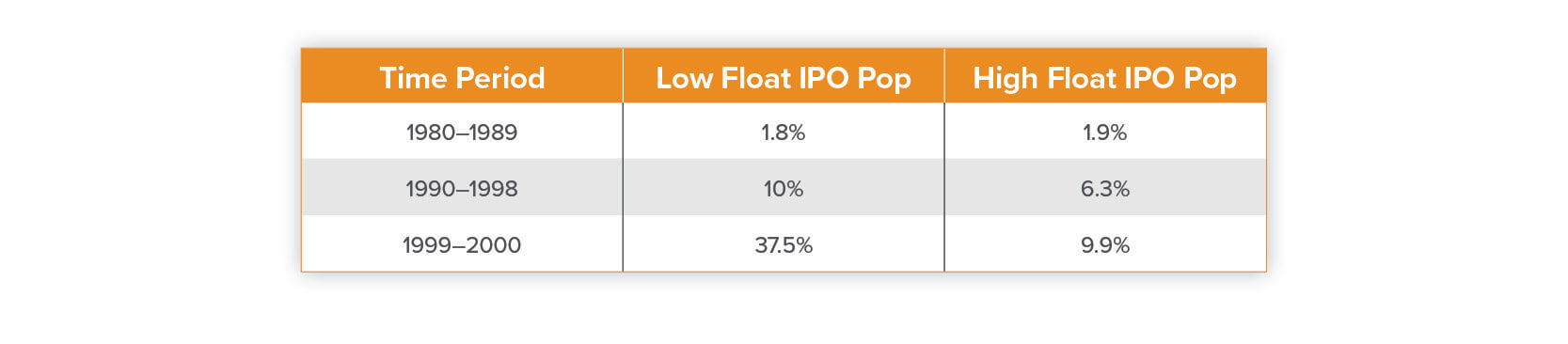

What you see from the above is that median floats were pretty consistent from 1980-1998, but dropped significantly during the dot-com bubble. Let’s add in some additional data – the median size of IPO pops broken out between low float stocks (<30% float offered at IPO) versus high float stocks (>30% offered).

With the exception of the 1980-1989 time period (where we know that IPO pops overall were the lowest), the size of the IPO pop is correlated with the float: Lower floats (meaning that there are fewer shares available to trade, aka low supply) yield higher first-day pops. In the dot-com era, the delta is nearly 4x!

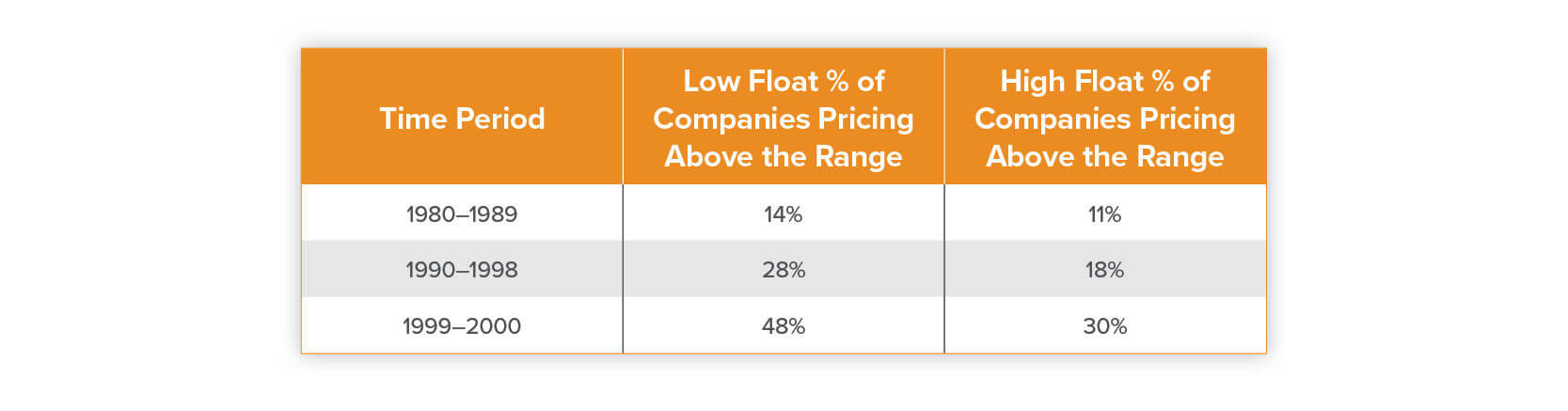

Recall above that we also talked about the demand side of the equation, using whether an IPO prices above, in-line with, or below its initial offering price has an impact on the magnitude of its IPO pop. We concluded that it does.

Here’s some additional data to underscore that. The below chart shows the relation between IPO float and whether companies priced above their initial filing range – the perfect interplay of supply (float) and demand (pricing above the initial filing range).

This makes sense. All things being equal, lower supply (float) should drive higher overall initial pricing. Other academic literature supports this theory, with some recent research showing that the effect is more pronounced in the tails – e.g., very low floats vs very high floats — and more muted in the middle range.

So, one very simple explanation for why we might be seeing significantly higher IPO pops in 2020 is a function of the average floats. At 15.5%, the median float is well below historical norms – even including the dot-com bubble. Thus, constrained supply will drive higher IPO pops.

Why are floats so much lower? One likely contributor is the fact that venture-backed companies in particular are staying private much longer (nearly double the 6-7 year time frame that we saw through the early 2000s). As a result, they are much more mature at the time of IPO (median revenue is about 10x what it was in the dot-com bubble) and thus often higher valued. Even assuming they wanted to raise the same amount of nominal dollars at the IPO as in the past, higher valuations means they can do so by issuing many fewer shares.

Are bankers simply irrational?

That brings us back to the bankers, and the perception that they are colluding with buyside investors on IPO pricing.

Bankers get paid for an IPO based upon a percentage of the amount of money raised by the company. Traditionally, that’s been a 7% fee, but as the size of IPOs has increased, many companies pay materially less. While it may seem that bankers want to price the IPO as high as possible to maximize the proceeds to the company and thus maximize the underwriting fees to the bank, then why do we still have IPO pops? Are bankers simply economically irrational? We don’t believe so; the arguments we’ve made here and in our prior post explain the actual reasons behind pops.

Nonetheless, opponents of IPO pops and the traditional IPO process believe that bankers willingly give up economics on an IPO (in the form of locking in the IPO pop for the buy-side) in exchange for getting more money down the round from investors in the form of “soft dollar commissions.” These commissions are a process by which an investor pays, say, $0.30 to a bank for a stock trade even though the real cost of the trade is substantially less than that. In effect, the investor overpays the bank in “hard” dollars and in exchange receives other services (e.g., sell-side research) for free. The monetary value of the free stuff is known as “soft” money. So, the argument goes that bankers are in fact perfectly rational – they willingly give up the certainty of some money in the form of their underwriting fee to curry favor with the IPO buyers who will repay them in spades over time through soft dollar commissions. This would also require a remarkable amount of teamwork and long-term optimization between a supposedly quarterly-bonus-hungry banker and other colleagues in the rest of the bank!

From the founding of the New York Stock Exchange in 1792 until 1975, trading commissions were fixed at 0.25% of the trade amount. Finally, in 1975, the NYSE and the SEC recognized that this was a bad idea and changed to the context of flexible commissions – aka competition. However, many banks had been bundling research as part of the commissions that institutional investors paid. So, to protect that behavior and still ensure that institutional investors were satisfying their fiduciary duties to their clients, Congress amended the 1934 Securities Exchange Act to add a safe harbor. That amendment – Section 28(e) – made it permissible to create the soft dollar regime that persists today.

But, across the pond, the EU in 2018 put in place a provision that required the “unbundling” of research costs from commissions, commonly known as MiFid II. There had been concern among the banking community that the SEC would implement a version of MiFid II in the U.S., but the SEC declined to do so, at least temporarily – the current relief expires in 2023.

What do the data tell us?

- Soft dollar commissions were very much in vogue from 1980-2000, but, as we’ve seen, IPO pops moved up in the nineties era and way up in the dot-com bubble era. This doesn’t suggest much of a correlation between the magnitude of pops and the soft dollar commissions. If there were a substitution effect, we would expect an inverse relationship between the two, which is not what we in fact see.

- A similar pattern persists in the 2000s. We’ve noted previously that the IPO magnitude over the 2001-2019 period was pretty flat to that in the 1990s, so no inverse relationship between pops and commissions.

- If you split that time period in half (2001-2009 vs 2010-2019) you do see a 19% increase in pop size: from 2001-2009, the IPO pops averaged 11.9%, whereas they reached 14.2% from 2010-2019. In the latter period, soft dollar commissions have declined by approximately 50%, so we do see at least some evidence of an inverse correlation, albeit in very different magnitudes. If these were substitutionary, we would have expected to see a much tighter correlation between the two variables.

Anecdotally, in the days leading up to the allocation process for an IPO, the lead investment bank on an IPO may often see an increase in the amount of trading volume for other securities allocated to its trading desk. We can debate whether this is fair or not, but it’s certainly economically rational behavior by the buy-side to potentially influence at the margin the amount of allocation they hope to receive in an upcoming IPO. This does not, however, impact the incentives around the magnitude of the IPO pop; if anything, it’s a competitive mechanism to fight for allocations, not an ask for lower IPO pricing.

As we’ve written about before, innovation in the IPO process that has the potential to enhance price discovery (e.g., creating a more refined demand curve at various price points) and address the supply-side of the equation (e.g., higher floats, innovative lockup structures) is long overdue. But, throwing out the IPO baby with the bathwater without understanding how we got here won’t help us get to a better state.

Ultimately, as it turns out, the data seems to show that it all comes down to the basic economic principles of supply and demand.

Thanks to Alex Immerman and Chine Mmegwa for their input.