What’s notable about recent mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity in software companies (including SaaS) isn’t the number of deals (7), their worth ($8.6B disclosed value), or even the timing (all took place in just the last 30 days).

What’s notable is whether this recent wave of activity signals the arrival of more growth — as opposed to consolidation — deals by acquirers.

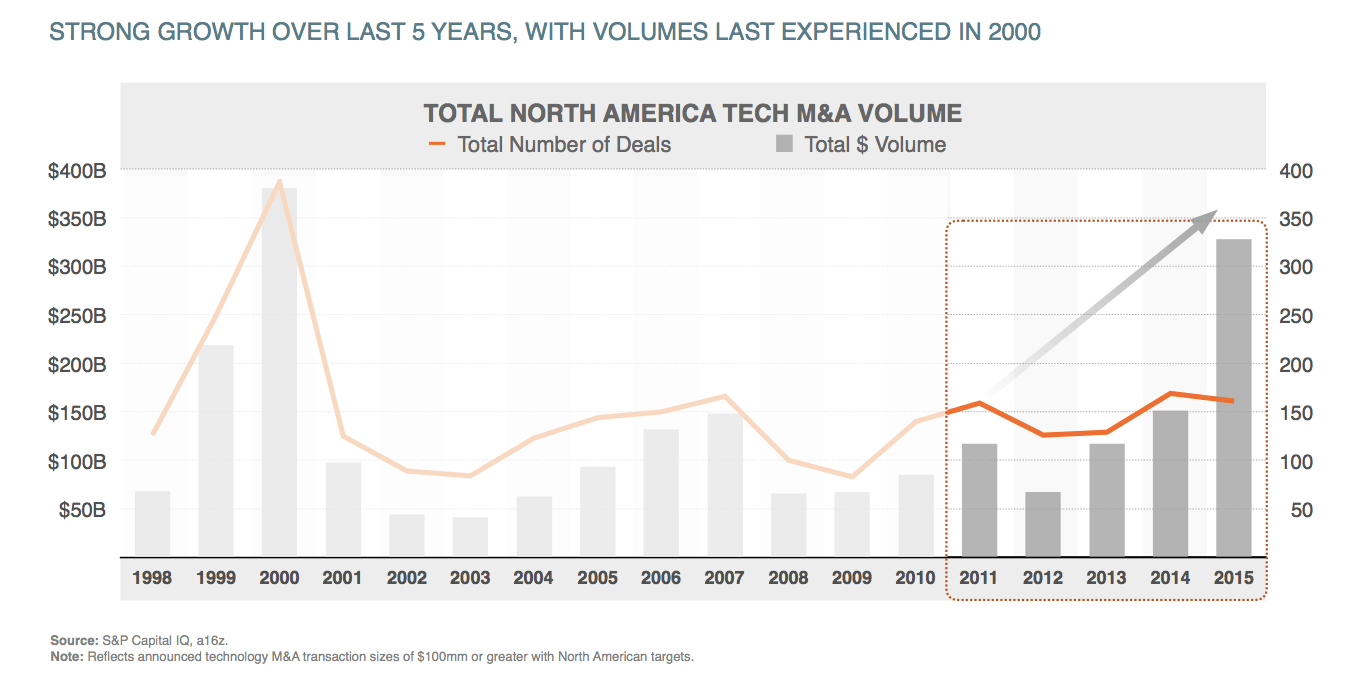

Why does that distinction matter? Well first, let’s take a quick look at the deals: four of the seven deals were private equity firms (Vista Equity Partners, Accel KKR, and Thoma Bravo) acquiring companies (Marketo & Ping Identity, Sciquest, and Qlik Technologies, respectively). That’s just business as usual in line with past tech M&A activity: Non-growth transactions in the form of going-private deals (or consolidation by large, established technology companies) have largely driven tech M&A volumes just shy of peak levels last seen in 2000.

overall tech M&A volume has been robust

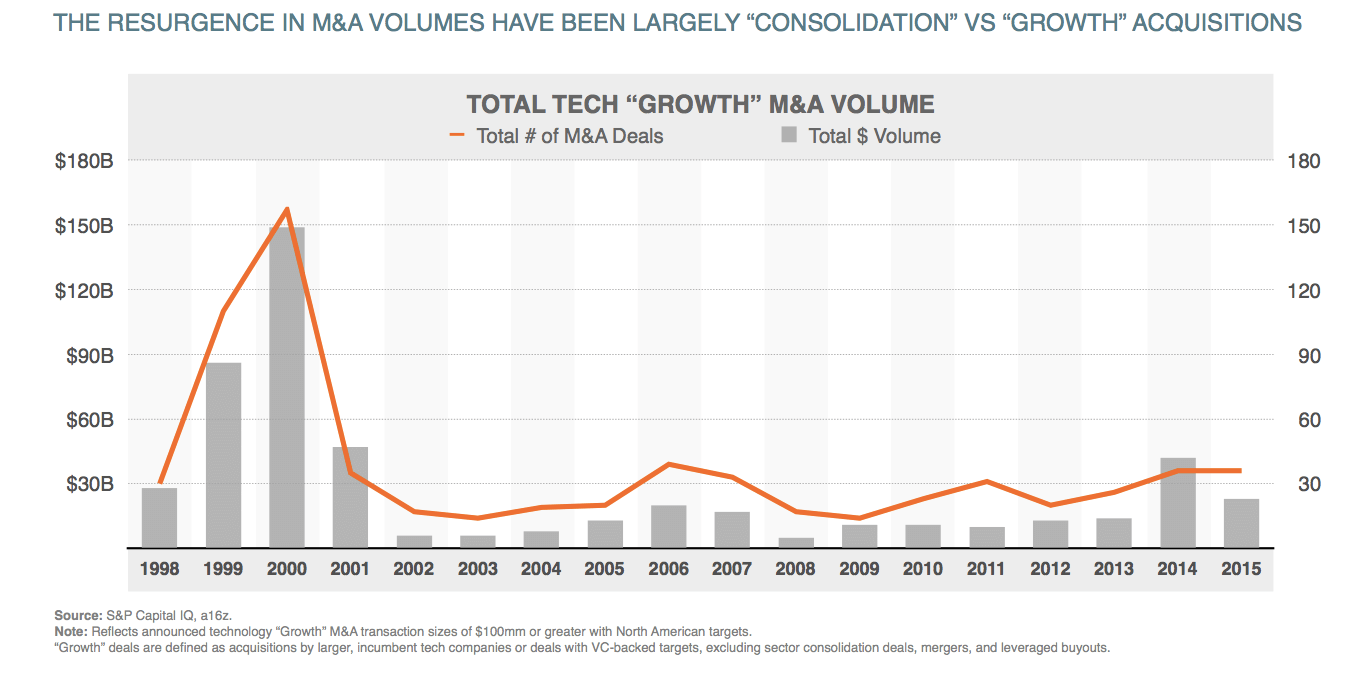

Since not all M&A is equal, the difference between non-growth and growth M&A is important as it signals forward-looking investment in a broader platform shift and new product cycles.

That’s why the other three recent cloud services deals — Salesforce.com’s $2.9B acquisition of ecommerce software platform Demandware and Oracle’s acquisitions of customer engagement and energy efficiency company Opower and construction contracts/payment management company Textura — are the ones worth paying attention to. They represent growth deals — product-line extensions, geographic extensions, and so on — orchestrated to increase top-line growth for the acquirer. As I’ve written about before, this has been a lagging area of tech M&A for the past 15 years and belies what was really happening underneath the superficial increase in M&A activity in 2015 (i.e., growth volumes represented only about 20% of peak 2000 levels).

But is there now more growth M&A activity on the horizon?

The question is whether the recent acquisitions by Salesforce.com and Oracle foreshadow the impending arrival of more “growth” acquisitions from other large tech incumbents, such as the likes of Cisco and Microsoft. To answer this question, it helps to look at the broader context of what conditions tend to drive M&A —

Condition #1: Declining core revenue growth

Tech is, by definition, a product-driven business. Products have cycles. Revenue tracks cycles. So when a company gets to the other side of a product cycle, revenue growth rates decline until the company finds a way to re-invigorate that cycle or, more likely, to invent — or acquire — a new product that is on the leading vs. lagging side of its product cycle.

IBM’s 16 straight quarters of declining revenue growth are an example of what happens when a company is on the lagging side of a product cycle. What remains to be seen is if their long-term bets in A.I. and blockchain (CEO Ginni Rometty recently revealed that they have over 200 experiments going) can help get them to the other side. With most companies in this position — that is, in between short-term product cycles and long-term investment payoff or seeking new directions altogether — we might expect them to look to M&A as a way to address that gap and decline in core revenue growth.

Condition #2: High cash balances

M&A requires money. A measure of a company’s ability to make acquisitions is the amount of cash on the balance sheet divided by the market capitalization of the company; if the result is high then that means the company has more degrees of freedom to use cash to fund acquisitions.

So, all things being equal, we would expect more M&A activity when companies have a high percentage of cash relative to market cap. The most innovative companies, after all, are the ones that re-invest their cash into future growth — not just as dividends to stockholders — so they can continue to stay ahead and build even greater value.

Condition #3: Increasing (or at least stable) PE multiples

Every company wants to make acquisitions when its stock is trading at all-time high price-to-earnings (PE) multiples. Especially relative to the target company’s PE multiple. Why? Because the earnings that the company acquires from the target company are valued post-deal at the acquirer’s PE multiple, which makes the deal more palatable to the existing company’s shareholders. Earnings dilution is bad and deters M&A.

But, if you can’t have all-time high PE multiples (as we saw in the 2000 tech bubble), then you at least want stable and increasing vs. decreasing multiples. Volatility in PE multiples makes it hard for boards to forecast dilution or accretion from M&A and thus makes them more likely to sit tight until multiples stabilize.

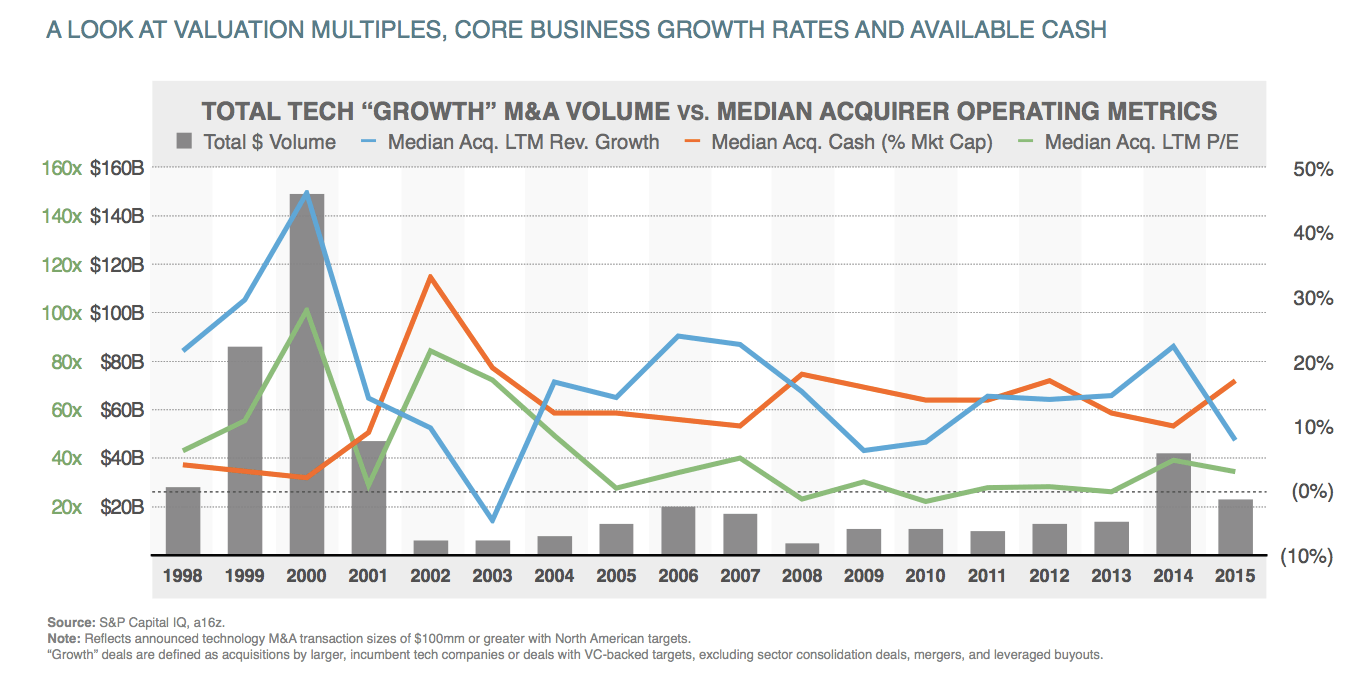

Given our above conditions framework for thinking about tech M&A, let’s take a look at what’s happening among the potential “incumbent” acquirer class.

Every successful startup, after all, goes on to become the new incumbent — and at faster time scales than ever before.

Note, when we talk about the “incumbents”, we mean large tech companies that have been public company leaders in their respective domains for a long time — EMC (now Dell-EMC), Google, HP (now Hewlett Packard Enterprise and HP Inc), Microsoft, Oracle, Salesforce.com, SAP, VMware (also part of Dell-EMC), etc. We’d contrast these with the “new incumbents” — companies that have gone public in the past five years or so that are now establishing themselves as potential new leaders — Facebook, LinkedIn, Servicenow, Splunk, Workday, etc. Every successful startup, after all, goes on to become the new incumbent — and at faster time scales than ever before.

what drives M&A?

The graph above shows the trends among the top tech incumbents against the three M&A conditions I outlined:

- Declining core revenue growth — Check! In fact, from the bubble peaks, where revenue growth was around 40%, this group is now looking at ~10% trailing revenue growth.

- High cash balances — Check! Cash as a percentage of market cap is approaching 20%, near the highs of the last 17-years. We haven’t seen levels higher than this since 2002, when we were in the doldrums of the post-bubble crash and market caps were near all-time lows.

- Increasing/stable PE multiple — Somewhat. While we are a ways off the peak 2000 PE levels of 140x, PE levels are still very robust and, most importantly, stable. Stability is more important even without super high multiples, because volatility is the enemy of M&A activity.

So if conditions are ripe for tech M&A among the incumbent group, why haven’t we seen more growth M&A to date?

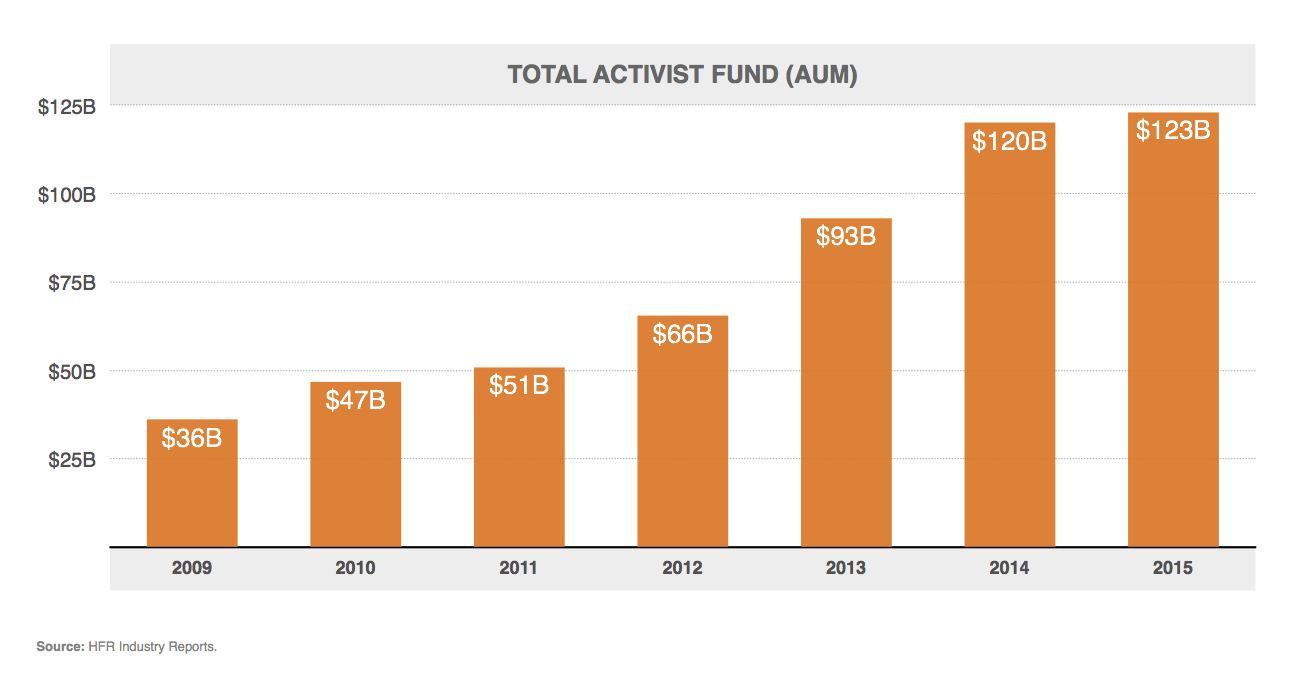

Well, it turns out that many of the same market characteristics that favor M&A also make companies prime targets for the activist shareholder crowd. Activists screen for declining core businesses with high cash balances because they want that cash returned to shareholders in the form of dividends or stock buybacks. This means those activist targets can no longer invest in growth — in the form of new product-cycle M&A or internal R&D — because doing so would depress their near-term earnings and consume excess cash.

And that’s exactly what’s happened in tech: As the amount of assets under management by activists has grown…

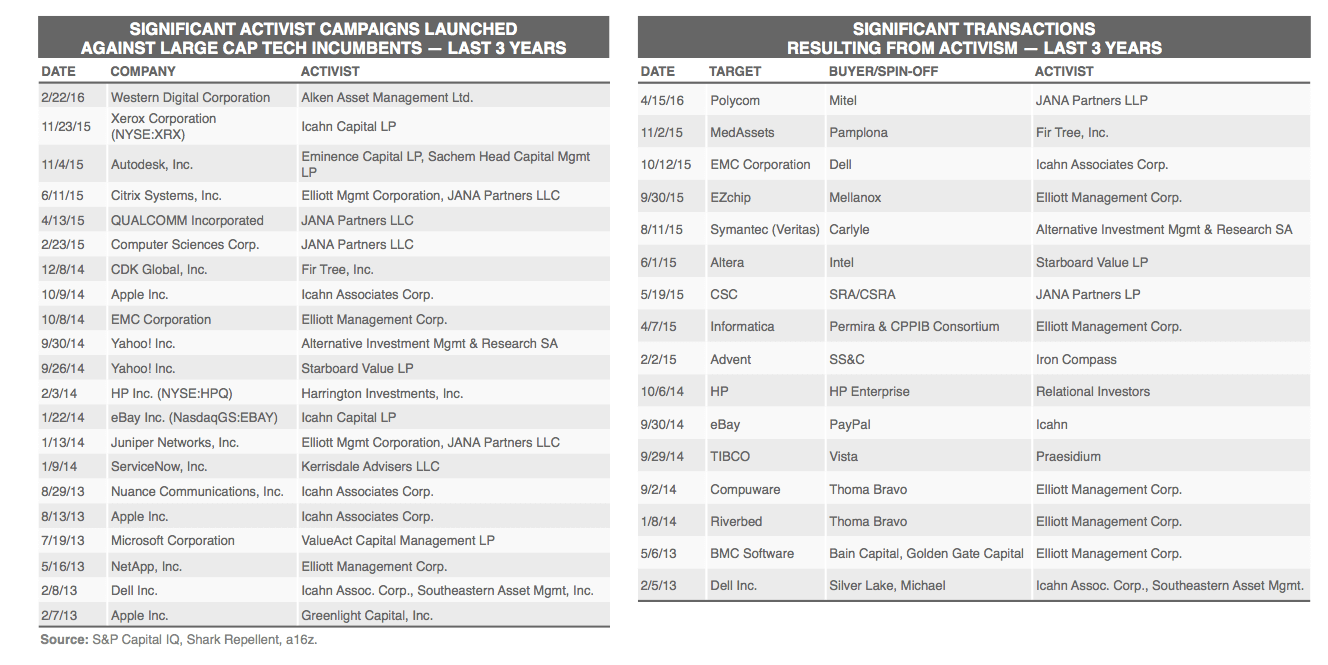

…so too has the level of activist engagement among the tech incumbent crowd.

activist targets

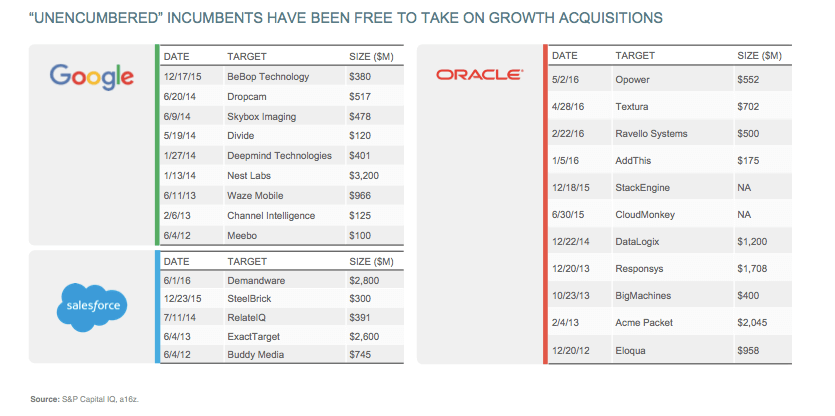

Notice what names are absent from the list of recent activist engagements above however — Salesforce.com and Oracle, both of whom feature prominently among the recent M&A activity.

So why have they escaped the wrath of the activists? Salesforce.com has, quite straightforwardly, done a great job growing the business. Even though their revenue growth rate has slowed over the past 5 years, they’ve still grown the top line roughly 5x over that time period. That kind of growth is kryptonite to the activists. And Oracle, despite having basically flat top-line growth, is roughly 25% controlled by its founder, Larry Ellison. That kind of shareholder control is another kind of prophylactic that protects against activist intervention. It’s for these reasons that Google, too (with its tri-class voting structure) has been an active acquirer among the incumbent crowd since it doesn’t have to spend time fighting activists.

“unencumbered” incumbents

The good news is that activists might now be dialing back their tech activity overall. Besides obvious reasons like declining returns/poor performance for this asset class, many tech incumbents that would otherwise be attractive activist targets are on the other side of the activist cash curve. Or as I like to think of it, they’ve already “given at the office” — most of them survived the activist cashectomy by returning cash to their investors in the form of dividends and buybacks, or by splitting themselves (as eBay and HP did). Which means those companies’ boards now have the freedom to re-constitute their shareholder base and pursue a growth agenda.

In fact, the M&A activity reveals a number of strategic growth deals on the heels of requited activist campaigns. Post-split, we’ve seen eBay make two acquisitions (Cargigi, Twice); Paypal make three (Cyactive, Modest, Xoom); and HPE make three of its own as well (Aruba, Contextream, Stackato). And maybe it was mere coincidence, but within days of notorious activist investor Carl Icahn announcing that he had fully exited Apple stock, Tim Cook announced Apple’s $1 billion investment in Didi Chuxing.

So the sky appears to be clearing when it comes to activists. But what then of the argument that regardless of the broader macro and incumbent picture, SaaS is inherently harder to acquire than classic on-premise software companies? Besides the evidence of $8.6 billion SaaS deals in the past 30 days, my experience on the other side — not just as an investor but as a former manager of HP’s global software support business — suggests that isn’t a likely deterrent to M&A.

While it’s true that it requires a higher customer success standard to be a SaaS vendor — you have to support a run-time environment for your customers instead of dumping on-prem software onto the company’s IT operations team to manage — it’s actually easier to integrate SaaS companies when it comes to acquisitions. Why? Because of the “versioning debt” problem inherent in the on-premise alternative. Simply put, on-prem software requires huge engineering, support, and professional services costs to maintain multiple, legacy versions of the software. And, perhaps more significantly, these costs become multiplicative when you add in acquisitions.

At HP, we had to support ‘n’ versions of every legacy product family — not just HP’s own Openview system, but products acquired from Opsware (which was how I came to HP), Mercury Interactive, Peregrine Systems, SPI Dynamics, and so on — each with its own unique configurations, integrations, and supporting back-end systems. The compatibility matrix of supported combinations made Microsoft’s massive device driver library look like a beach-read novelette!

Software-as-a-Service rids us of the versioning debt problem

SaaS mostly rids us of the versioning debt problem by shifting the onus from the customer to the vendor, who determines the size of the compatibility matrix. (Not to mention that the SaaS vendor also has the data across multiple clients to make sure things really work given the inherent multi-tenant architecture of SaaS).

None of this is meant to trivialize the support required of SaaS vendors to ensure customer success, but it does reduce a barrier to M&A activity relative to traditional on-premise solutions. And owning the responsibility for the success of your customers — as SaaS vendors must do — is a great form of long-term customer-relationship management and stickiness. Instead of sitting on the shelf unused as often happens with on-prem software, SaaS products are actually used — tying the runtime success of the customer to the success of the vendor. There’s no better example of an alignment in incentives that ensures SaaS M&A would be more successful in the long run.

* * *

Ultimately, when it comes to software, SaaS, or any other M&A it’s useful to view it through the lens of “growth or non-growth?”; we can’t treat both the same when it comes to objectives and outcomes. You can’t judge a SaaS deal book by its cover.

And only time will tell whether “growth” M&A among the tech incumbents is on the rise — or whether the activity of the past 30 days is simply a flickering mirage in a long-dry desert. But, if conditions remain ripe and the activist barrier is indeed on the decline, growth may be on the horizon.