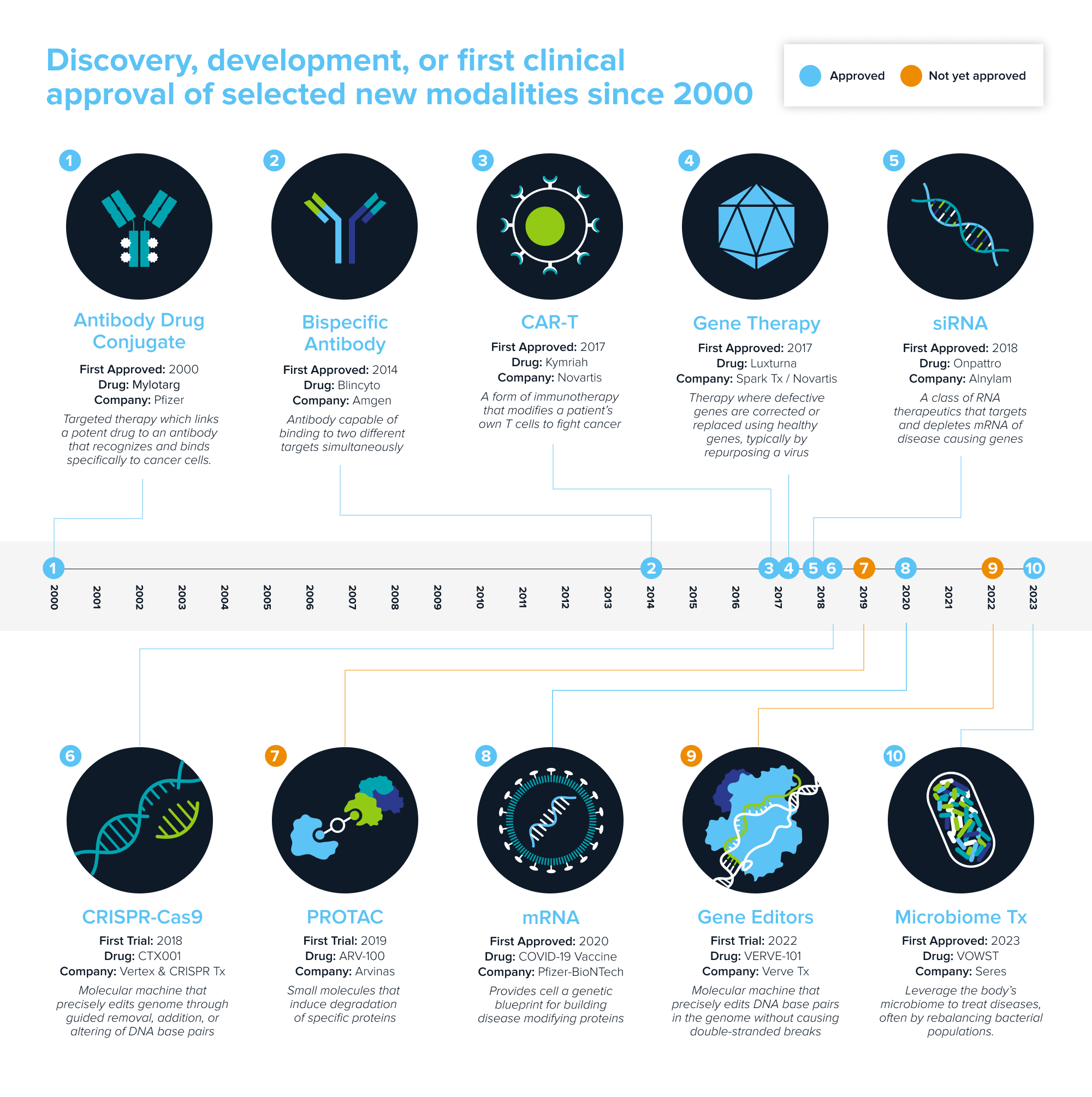

We are firmly in the century of biology. The last two decades have seen explosive advancement in biomedical and therapeutic innovations, like the Human Genome Project, the discovery of CRISPR, and the rapid development of Covid-19 mRNA vaccines, to name a few.

This rapid innovation has been fueled by an unprecedented amount of investment. Despite the recent slowdown, venture capital investment in the biotech sector in the US ballooned to nearly $25 billion in 2022 from just under $4 billion in 2000. Pharma R&D investment likewise increased from $38 billion in 2000 to $83 billion by 2019.

These investments have yielded an extensive array of new types, or modalities, of medicines. Each new modality—like gene therapy or RNA-based medicine—gives us new capabilities that expand our therapeutic armamentarium. As they enter our pharmacopeia, they enable us to tackle disease in new ways and even pursue previously intractable conditions.

Source: Andreessen Horowitz research.

Each new modality needs to find its platform-disease fit—the diseases it is uniquely suited for. But finding fit has increasingly turned into a fight; many have crowded into the same indications. With an expanding arsenal to treat disease, how will patients, clinicians, and the market determine what tool to use?

Herding class

Drug development is a competitive sport. Typically, the first drug to get across the finish line, wins: first-in-class drugs become the standard of care, dominate market share, and tend to maintain that advantage even after new entrants arrive. Companies with first-to-market drugs are better versed on the market, and treating physicians like prescribing what they know. They’re the ones to beat.

“If you’re not first, you better be bringing something worthwhile. We spend a lot of time talking to doctors trying to really get a flavor for how satisfactory is that first mover? If the answer is pretty darn good, then it’s gonna be very hard to displace,” says Josh Schimmer, MD, of Cantor Fitzgerald.

If you aren’t first-in-class, you need to raise the bar and become best-in-class. Fast followers have caused “herding in the drug development pipeline;” 68% of targets pursued by top 10 companies face at least five competing assets. Crowding stifles innovation and bottlenecks clinical trials—there are 56 PD(L)1s currently in development! But late entrants have proven there’s opportunity in improvement, as demonstrated by the GLP-1 drugs vying for obesity’s massive market: Novo Nordisk’s first-in-class Wegovy and Ozempic will likely be overtaken by Eli Lilly’s recently approved and more efficacious Zepbound.

Class warfare

The arrival of new modalities can dramatically shift these dynamics. Potentially curative approaches, like one-and-done gene therapies, have raised the prospect of last-in-class therapies. With a curative therapy, the market could become fully captured as patients are cured. Earlier this year, eight clinical programs were pursuing sickle cell disease. After Vertex and CRISPR Therapeutics submitted their cell therapy for FDA approval, three rival programs were quickly shut down.

But the same rules may not apply when different modalities enter the same disease indication. The “best” therapy should win the market but it’s of course not that simple. Each modality brings its own pros and cons and different patient segments will weigh them differently. So in addition to bringing patients much-needed hope, these new medicines will offer them choice as well.

“Best” will become increasingly subjective, but here are some of the factors that can determine a new modality’s position on the commercial battlefield:

Affordability, accessibility, convenience

Drug affordability and access is a moral and economic imperative. New modalities are often challenging and expensive to develop and manufacture—gene therapy can be $2 million+ per dose! Many patients simply cannot afford or access them, so less expensive approaches like small molecules are more likely to reach those patients. Convenience matters too. Some may prefer a one-and-done gene therapy; others might find it more convenient to take a pill every day.

Curative potential and safety

The most safe and effective therapy should win. Gene therapy and editing approaches offer the promise of one-and-done cures, but they’re also permanent; patients cannot be taken off the drug if safety issues arise. Small molecules or oligonucleotides don’t have that same drawback but are less likely to be curative. Safety and efficacy can be two sides of the same coin.

Programmability

Traditional modalities like small molecules are highly bespoke; one molecule has little bearing on the next molecule that gets developed. Newer modalities like gene therapy are inherently programmable—they can reuse components, like the delivery vehicles used to target specific cells while swapping out the genetic cargo, enabling several programs to be generated from the same underlying engine. Companies with programmable modalities may be able to develop de-risked drugs, faster and cheaper.

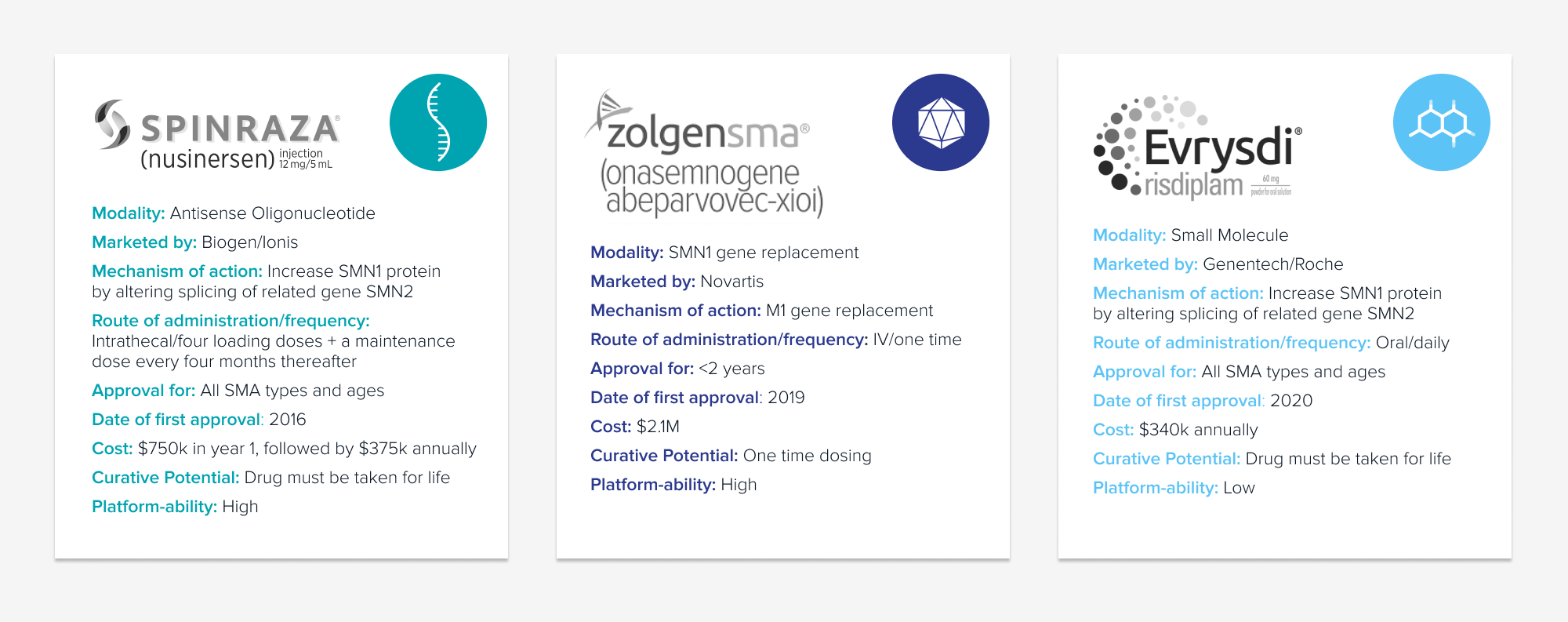

These dynamics are already playing out for a handful of indications crowded with differing modalities. Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a real-time example.

Working classes: the evolving SMA market

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a rare genetic disease that affects roughly 10,000-25,000 people in the US and is the leading genetic cause of infant mortality. SMA is caused by mutation of the SMN1 gene and results in loss of motor neurons and progressive degeneration. Treatment was historically limited to supportive care. The prognosis was bleak. But in recent years, three therapies that target the underlying genetic causes of SMA—by making more SMN1 protein—have emerged, each a different therapeutic modality.

Despite the massive impact of these three drugs on patients, there is still work to do in SMA. Patient access and newborn screening remain a priority.

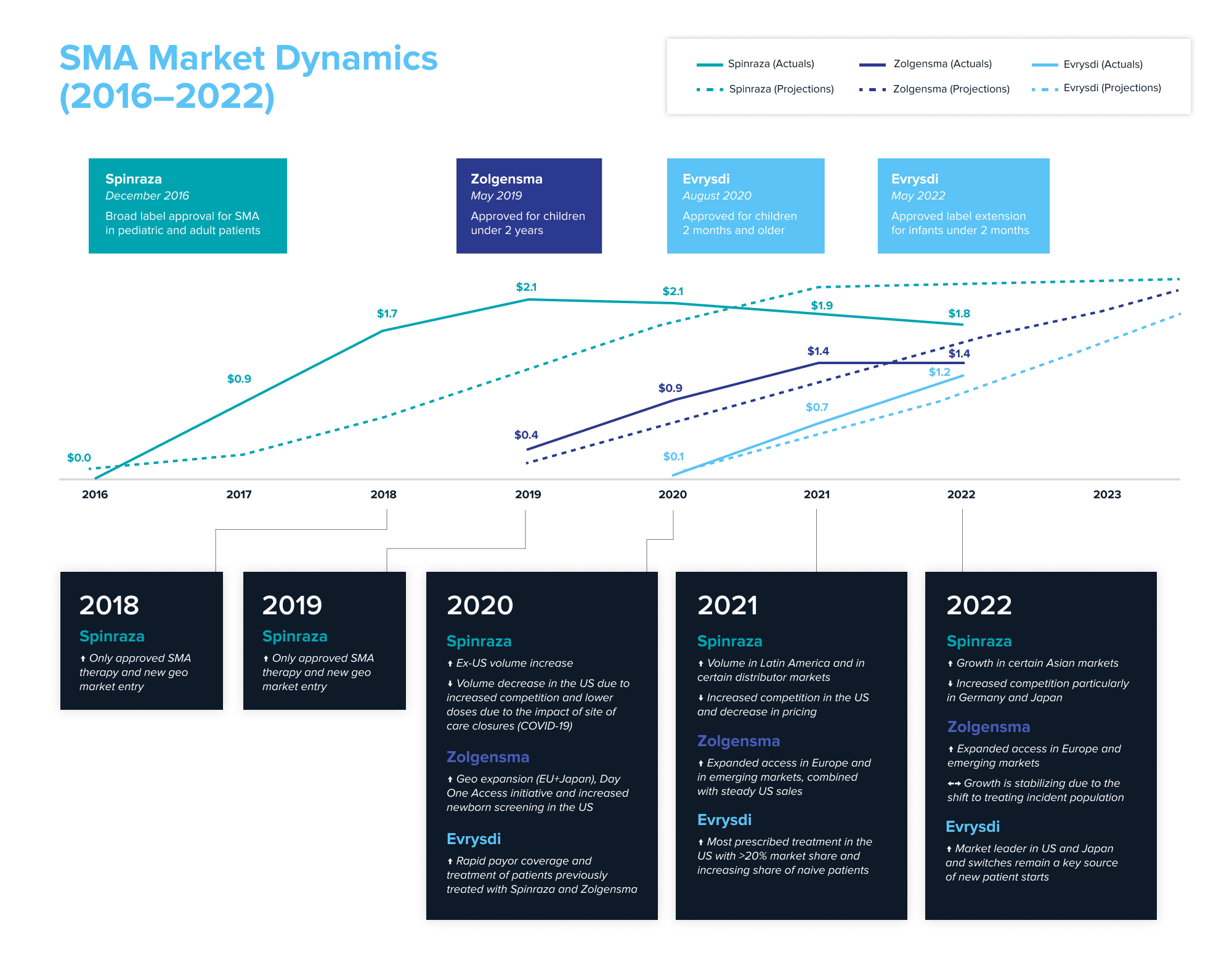

First approved in 2016, Biogen and Ionis’ Spinraza is an antisense oligonucleotide that revolutionized the treatment of SMA. Even though it’s administered through an invasive spinal injection every four months throughout the patient’s lifetime, Spinraza had a first-to-market advantage in a market with significant unmet need. In its first year after launch, Spinraza generated $884 million in worldwide sales, growing to ~$2.1 billion by 2019.

In 2019, Novartis’ Zolgensma became the second approved drug. An AAV-based gene therapy with potential for a one-and-done lifetime cure, it was approved for infants less than two years of age. But it comes with a hefty price tag of $2.1 million and questions about its safety and lifetime durability. Regardless, Zolgensma emerged as the market leader in newly-diagnosed infants upon approval, generating $920 million in its first full year after launch. It became the physicians’ preferred medication; no doctor was inclined to wait before initiating treatment.

In 2020, Genetech’s small molecule Evrysdi entered the treatment landscape. Evrysdi is taken orally daily and must be taken throughout the patient’s lifetime. It was an instant hit in the US—one year from launch, it became the most prescribed SMA treatment with over 16% market share. In the first full year after launch, Evrysdi generated over $650 million in worldwide sales, almost doubling its sales the following year.

To understand the success of the launch of the three marketed medicines, we examined equity research analysts’ product projections within a year of launch and then compared it to the actual sales each one of them generated. Source: Annual reports and company filings; projections from equity research reports.

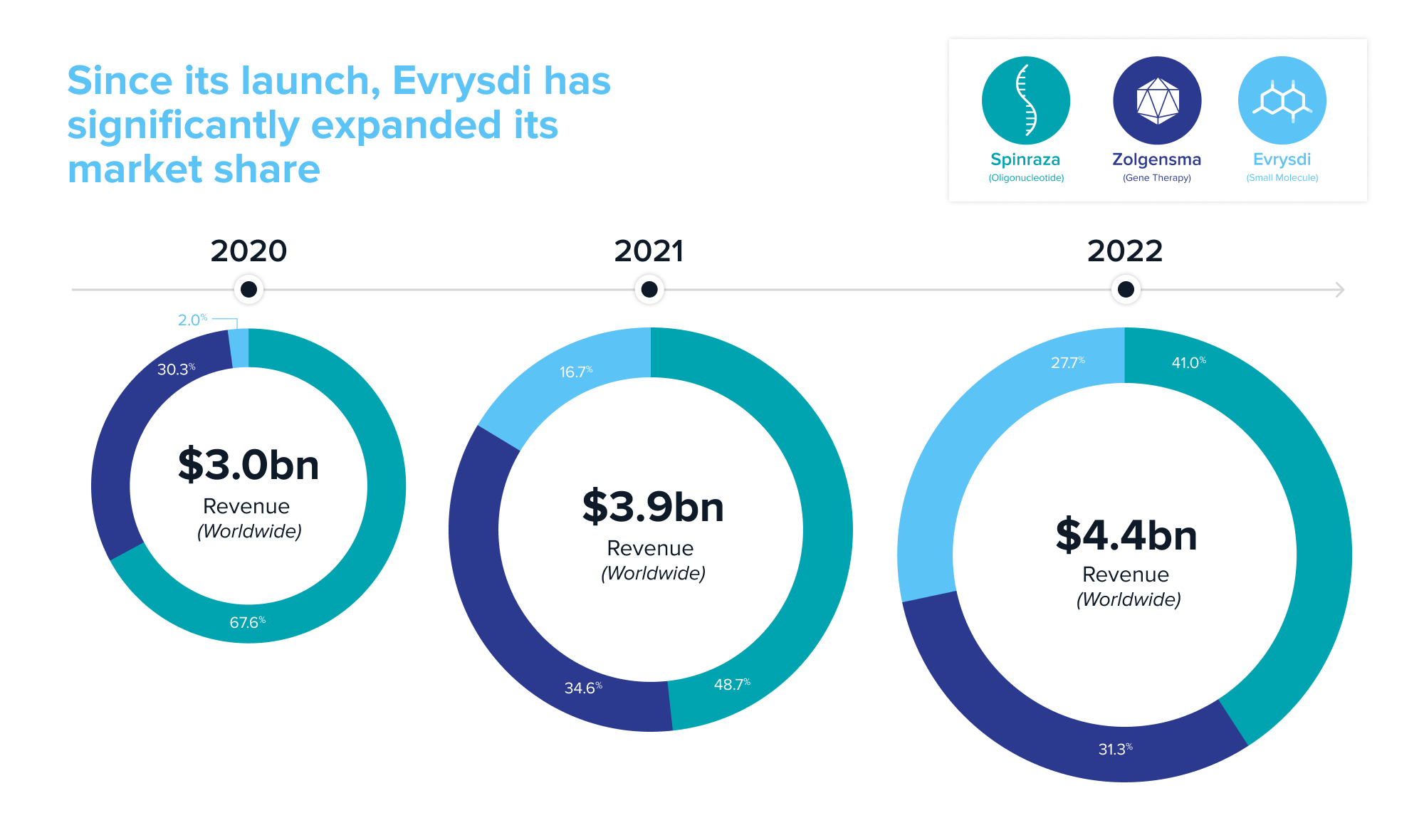

What can be learned from the market dynamics playing out in SMA? The first-mover advantage was real for Spinraza. Biogen remains the revenue leader, having generated approximately $10 billion over Spinraza’s lifetime (as of YE2022)—value creation that resulted in a recent $1.1 billion royalty deal. New entrants with better long-term efficacy potential and convenience are catching up with Spinraza. Despite difficulties with patient access and its high cost, Zolgensma has become a blockbuster. Convenience of dosing helped Evrysdi quickly gain market traction. While the newer entrants took and will likely continue to take market share from Spinraza, the arrival of new modalities has expanded the total market by nearly 50% in just two years, from $3.0 billion in 2020 to $4.4 billion in 2022, as more patients get access to treatment with each new drug.

Source: Annual reports and company filings

SMA is just one example where different modalities battle for market share. Moving forward, we expect emerging competition within Factor XI anticoagulation, hypercholesterolemia, Alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency, CD19+ tumors and autoimmunity, among many others.

Class dismissed

The advancement of new therapeutic modalities is great news for patients. But how should company builders and investors think about indications crowded with modalities? Aside from identifying new and better targets to pursue, the easy answer is that it’s complicated and context dependent. But here are a few takeaways:

Efficacious and safe drugs win

Perhaps an obvious statement, but in a world with many different modalities, the best patient outcomes should always win.

It pays to be first, so get there quickly

There is immense value to be gained from arriving first to a market, even if your market share is eventually supplanted.

Your new modality could be last-in-class

A first modality on the market may not necessarily prevent other modalities from entering, but is positioned to become “first and last-in-class” within the same class (i.e. the first curative gene therapy may prevent other gene therapies from entering).

Don’t forget about the patient

The physician and patient experience is critical when developing an innovative new modality. Convenience, pricing, and patient/clinician risk tolerance should be considered from the outset.

Small molecules can do big things

A general rule of thumb: all things being equal, a small molecule is preferred. Convenience and price point are big factors. Newer modalities may raise the bar but small molecules are beginning to achieve many feats previously only thought possible by other modalities.

There’s room for multiple modalities

Due to differing patient risk appetite, physician preference, and affordability, several modalities could be viable in one space. To make a dent in an indication space, companies must be able to clearly articulate what value their new modality brings and why it is differentiated from others.

Thank you to Josh Schimmer, MD, and Jonathan Strober, MD, for agreeing to speak with us and sharing their perspective on this topic.