Nobody puts Baby in a corner — especially if Baby happens to be fragmented financial services data. Historically, the key to building a successful financial services data company has been to extricate and analyze valuable but difficult-to-access resources like public filings, diligence materials, research reports, conference call notes, and news. Now, with the advent of large language models, such previously shackled information might soon be easily and widely available to everyone, ushering in a new LLM-powered era that could shift the financial services landscape.

That said, the financial services data market is currently dominated by several billion-dollar companies that, given their scale and other advantageous moats, are extremely entrenched. But Bloomberg, Morningstar, and Verisk — three prominent examples — didn’t become market leaders in a vacuum. All initially followed a specific three-step playbook at the dawn of the digital age, whereby they 1) identified large, fragmented pools of data in valuable markets; 2) found a way to bring that data into a relational database; and 3) charged for access to that information. In doing so, each built the beginnings of what are now category-defining businesses.

For new entrants looking to take advantage of the advent of LLMs and disrupt the status quo by going upstream of these incumbents, we’ve done a deep dive into Bloomberg, Morningstar, and Verisk’s stories. Here we’ve pulled out several instructional lessons for startups, as well as posed a few questions about issues that you should be thinking about. Let’s get started:

Bloomberg

Michael Bloomberg famously founded Bloomberg L.P. in 1981 after he was fired by Salomon Brothers, where he had been responsible for analytical tools for sales and trading. Having seen the massive amount of paper the investment bank had gone through to update their daily trades and prices, Bloomberg used his $10 million severance package to build an independent IT solution, initially called Innovative Market Systems, to bring firms that needed it the same type of data and simple analytical tools.

Prior to Bloomberg — and its aggregated financial data — entering the scene, firms had to collect data independently, often relying on calculators. By being the first one to accurately and quickly capture this data in a digital format, Bloomberg was able to gather users in a way that allowed his business to add on additional products and features, most important of which became communication.

Though Bloomberg was able to continue building his business by acquiring offline businesses like John Aubert’s Sinkers, which published corporate bond prices in a reference book, the big unlock came when the company took on Merrill Lynch as their first design partner. Not only was this association critical for brand trust and recognition, but by powering Merrill’s growing bond trading operation, Bloomberg was able to acquire real-time data from a market leader. And because this data ended up being better than what all the other platforms had at the time, Bloomberg ended up powering the daily bond prices for the Wall Street Journal, even though Dow Jones, the WSJ’s parent company, provided a competitive product.

What Bloomberg realized, and what set it apart from competitors like Datastream (now Refinitiv), was that a data advantage built on information that cannot be cornered won’t last forever. So the company was quick to couple its early lead with additional services, such as news and communication tools. Without the data and distribution that the terminal provided, Bloomberg would never have been able to compete with Dow Jones and Reuters, the two largest incumbents at the time.

Despite the incredibly rich data feeds, analytical models, and real-time news, the most valuable aspect of Bloomberg is the social aspect. The data and news brought all of the appropriate users onto the terminal and created a network effect lock-in that rivals any other social network.

Lessons for Startups

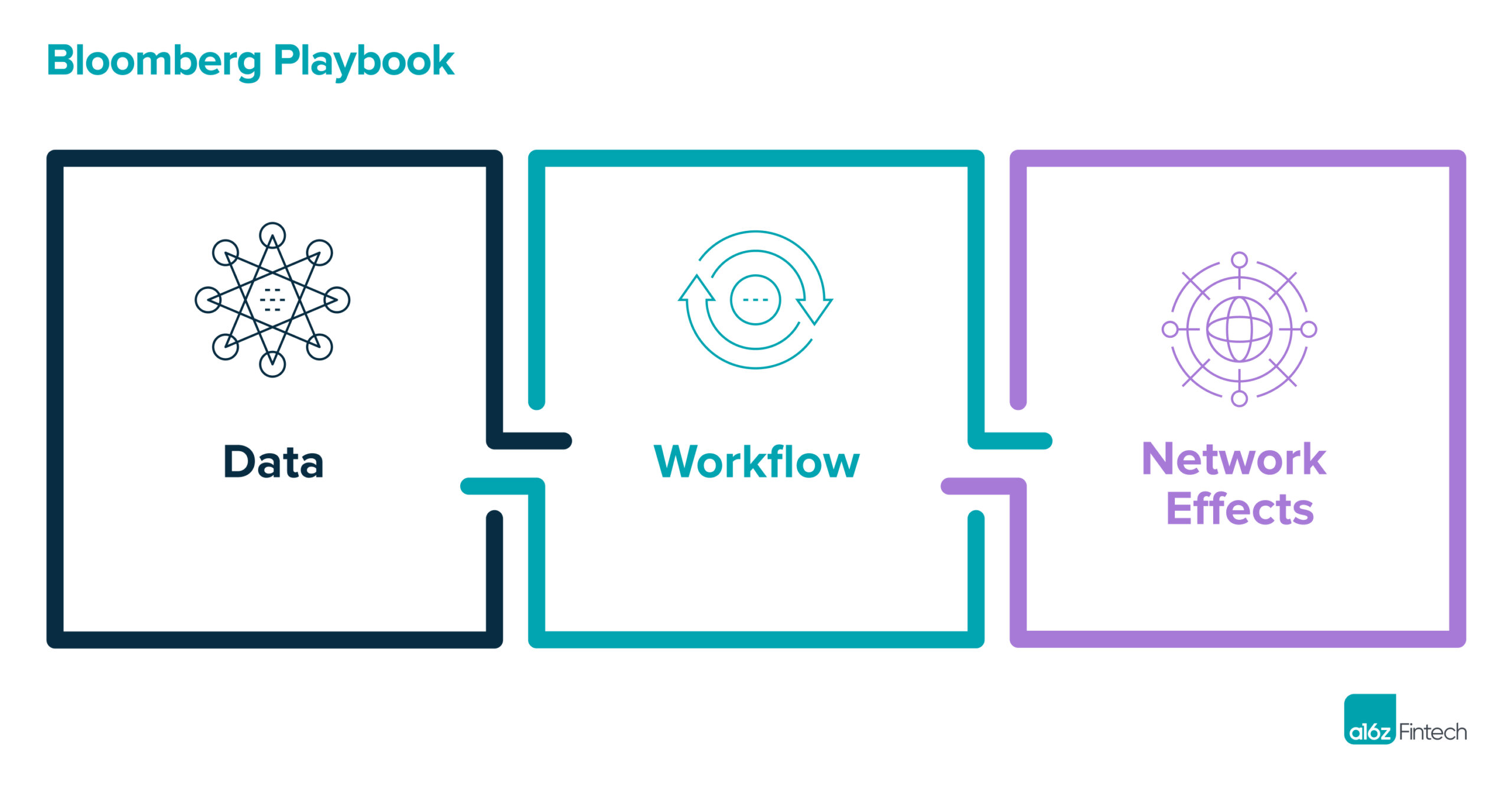

Bloomberg’s initial insight was to corner hard-to-access data and give it to customers in a usable format. To do so, it acquired a legacy offline business and used that to partner with a large player to further its data advantage. Bloomberg’s greatest insight, however, was that beyond continuing to innovate in financial data, its most significant value came from owning workflows and creating network effects driven by its communication tool.

Questions for startups:

- What data is Bloomberg not capturing properly today?

- Is there a workflow that isn’t well captured by Bloomberg?

- Are there groups your product serves that might benefit from a closed network communication center?

Morningstar

Morningstar was founded by Joe Mansueto in 1984 after he realized that mutual funds were on the rise but there was no good system to assess the quality of them. The holdings and reporting data needed to accurately assess the quality of mutual funds existed in various prospectuses, shareholder reports, and price histories, but acquiring this data was painful; analysts had to physically write to each fund’s managers to get access to their reports. After Mansueto realized that everyone who wanted to invest in mutual funds — from retail investors to large limited partners (LPs) representing many smaller investors’ capital — had to go through the same process, Morningstar was born.

Mansueto’s original idea was realizing that just aggregating all of this data into one, searchable place was a product in itself, and his first product was a book that was marketed in Barron’s and available 4 times a year; eventually, this database became the digital Morningstar product. Over time, Morningstar has leveraged its initial advantage in data aggregation and moved into additional verticals. This has predominantly happened through acquisitions, and Morningstar can immediately increase the value of these businesses as it has an established sales channel and an industry-leading brand.

One early driver of Morningstar’s success was mutual fund LPs insisting that their funds use Morningstar for their analytics and reporting. These LPs needed an easy way to explain to their investors what they were investing in and why, and they knew they could trust Morningstar’s research and data due to the business’ early expertise and reputation. Once LPs started driving this requirement, the industry standardized around it and Morningstar’s brand positioning was cemented.

Despite not owning any core workflows or collaborative element, Morningstar has a near monopoly on fund characterizations, and it has used the higher profit margins that come from a powerful brand to continue to acquire other businesses that have cornered interesting pools of financial data. Perhaps the most interesting of these acquisitions is Pitchbook, which both has unique data and is a workflow tool that might help Morningstar create a more Bloomberg-like relationship with its customers.

Lessons for Startups

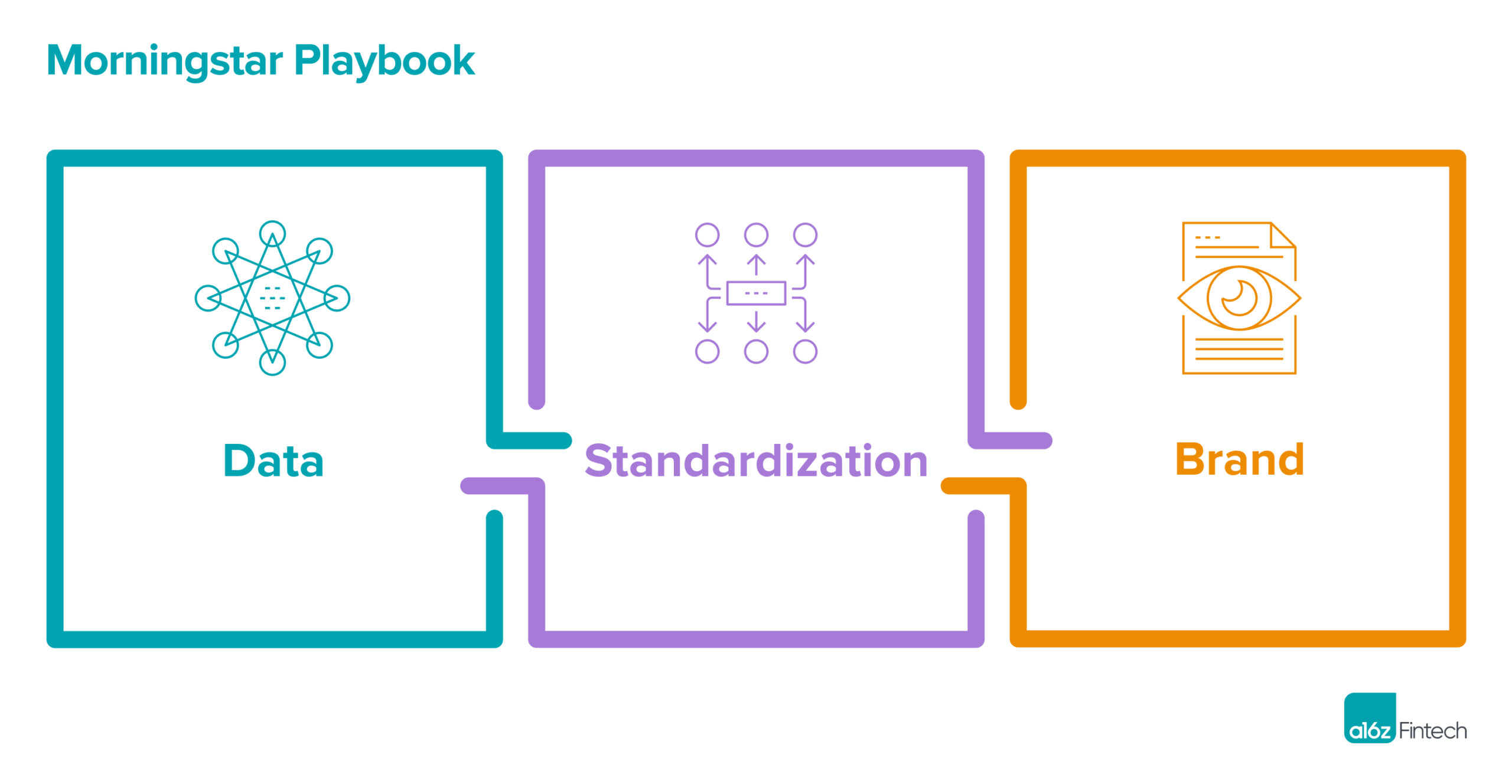

Morningstar is another classic example of an early financial services player understanding the value of aggregating challenging-to-access financial data and making it available in real time.

What is unique about their strategy is how they leveraged LPs to push the industry toward adopting their offerings. At the end of the day, mutual funds serve at the pleasure of LPs. When enough large, institutional LPs push for a certain reporting requirement, it happens and funds standardize, creating a brand moat.

Questions for startups:

- Is there a tailwind “why now” moment for the data you are capturing to become more valuable?

- Are there players (customers, regulators) in your industry that want to help drive adoption of your product?

- Is there whitespace for a brand around what you are offering?

Verisk

A non-profit consortium of 7 large property and casualty insurers founded the Insurance Services Office (ISO) in 1971 to be a neutral third party that could help with statistical and actuarial services, insurance programs, and state regulatory requirements. Realizing the significant value in standardizing and aggregating the large swath of insurance ratings bureaus, ISO, now a subsidiary of Verisk, was able to consolidate a massive amount of data. That gave carriers who accessed it greater economies of scale when it came to pricing and underwriting risk, and it was the start of Verisk’s data flywheel.

To further solidify and grow its data advantage, ISO expanded beyond ratings bureaus themselves and began standardizing ratings and forms. Modifying ratings schedules was particularly important in hard-to-insure categories like fire risk, where ISO created a single nationwide fire rating schedule that is still used today. At the same time, ISO created a vastly simplified personal lines (home and auto) insurance policy document that made it easier for a policyholder to understand what was covered by a policy. This standardization increased brand awareness and trust, as well as gave Verisk ownership over the data ingestion format.

Outside the obvious financial incentives, the advent of the internet and the ability to share its information online was a main driver behind converting ISO from a non-profit organization to its current for-profit status as Verisk Analytics. In the late 1990s, ISO launched ClaimSearch and combined additional claims datasets with what it already had and became the industry’s largest claims database. In becoming the first provider of online claims and pricing information, ISO continued to acquire more users, and data, further increasing its positioning as the leading provider of insurance data solutions.

Lessons for Startups

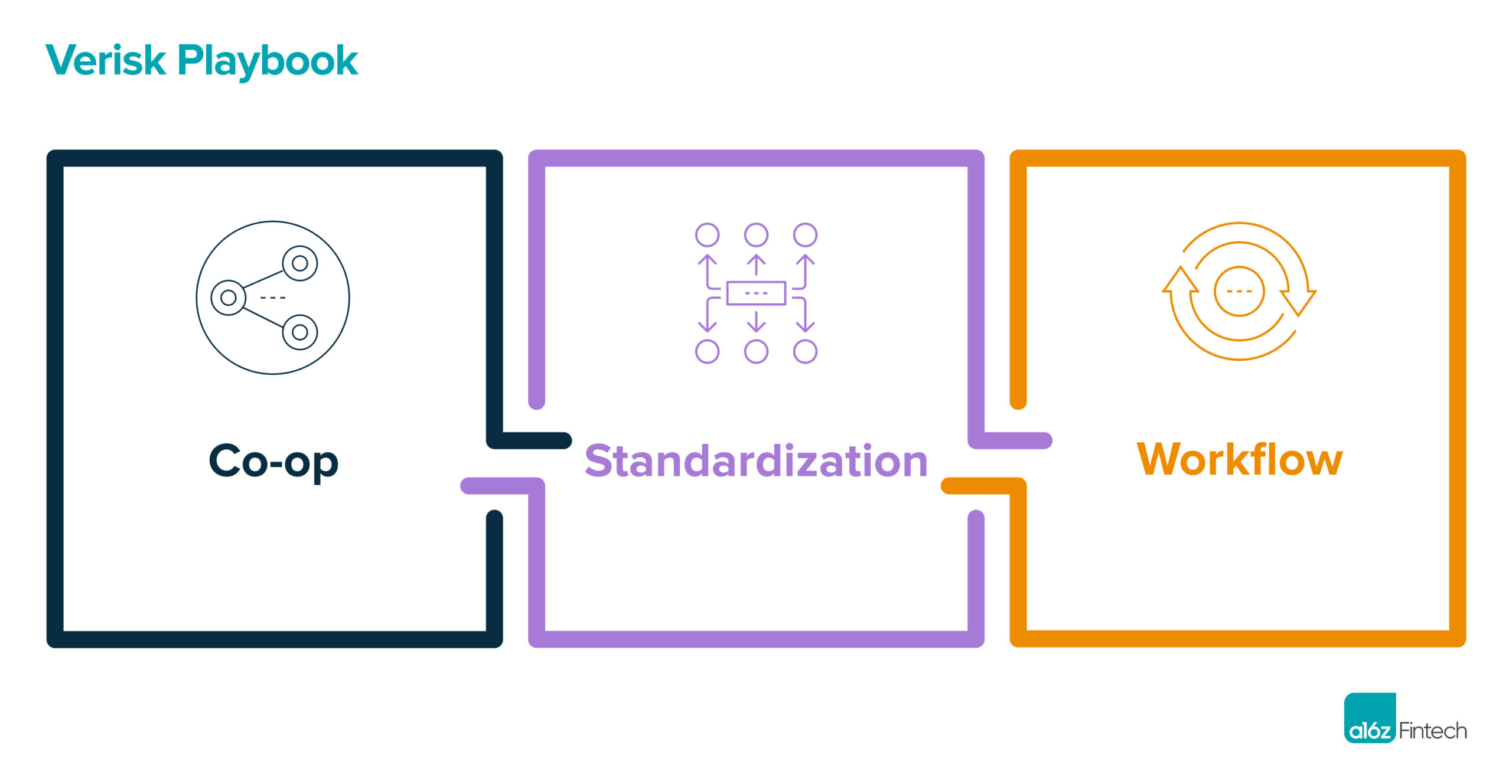

Verisk is unique as it started as a nonprofit dedicated to helping insurers better understand risk and claims data. At the time, the regulatory environment created the fragmentation of data, and building a new business was the best way to fix that problem. Offering better claims and risk data by creating a powerful give-to-get data exchange model solved the cold start problem of getting data that is valuable to carriers and regulators. In turn, carriers and regulators helped push the industry toward Verisk and cement its scale advantages.

Questions for startups:

- Are there significant data issues in your space that require industry collaboration but need a neutral third party?

- Do regulators want to drive substantial change in your industry? How might you position your company to be their instrument to drive forward this change?

- Is there a way you can drive standardization of fragmented workflows that leads to interesting data exhaust?

Conclusion

The rise of dominant market leaders Bloomberg, Morningstar, and Verisk has been characterized by a playbook centered around identifying large, fragmented pools of data and leveraging technology to provide valuable insights and solutions.

These companies have built category-defining businesses by capturing historical data, standardizing it, and offering it to customers in a simplified, accessible format that is enhanced by additional services and features that drive home defensibility. The advent of LLMs heralds a new era in data analytics and financial services. With the potential to unlock previously inaccessible data sources, LLMs may create opportunities for new players to emerge and disrupt the status quo by going upstream of these incumbents.

*A special thanks goes to Tom Elnick, the Co-CEO at Tegus. Tegus is one of my favorite products and a fantastic new example of success in this mold.