It’s time for your startup to fundraise. You prepare a deck, practice your pitch, and start reaching out to investors. If a first meeting goes well, it often ends with a request to share your “data room.” But what is a data room, and what should be included in it?

What is a data room?

The term “data room” is a holdover from the 1900s, when companies used to print physical documents and present them in secure rooms for investors and other prospective partners to review. Today, data rooms are virtual — but they’re still an important part of the diligence process.

Data rooms are also a key part of the preparation for other liquidity events like IPOs or SPACs, but here we focus on the importance of data rooms when raising venture capital. Here’s what founders need to know, including what data investors are hoping to see, the documents you don’t need, and red flags to look out for.

Data room 101

To start, a data room is a collection of documents that helps investors get up to speed on your business. The goal of a data room is to give investors the information they need to do their due diligence on your company (and eventually write an investment memo to discuss with the rest of their team). Here are the top five things we recommend including:

1. Pitch deck. This could be an entirely separate post! At a minimum, the deck should include your company’s thesis, product vision, competitive landscape, traction, and team, as well as a rough road map or plan for how you will use the funds.

2. Cap table. This should show the current investors in your company, how much they’ve invested, and how much ownership they have. Carta has some great free templates.

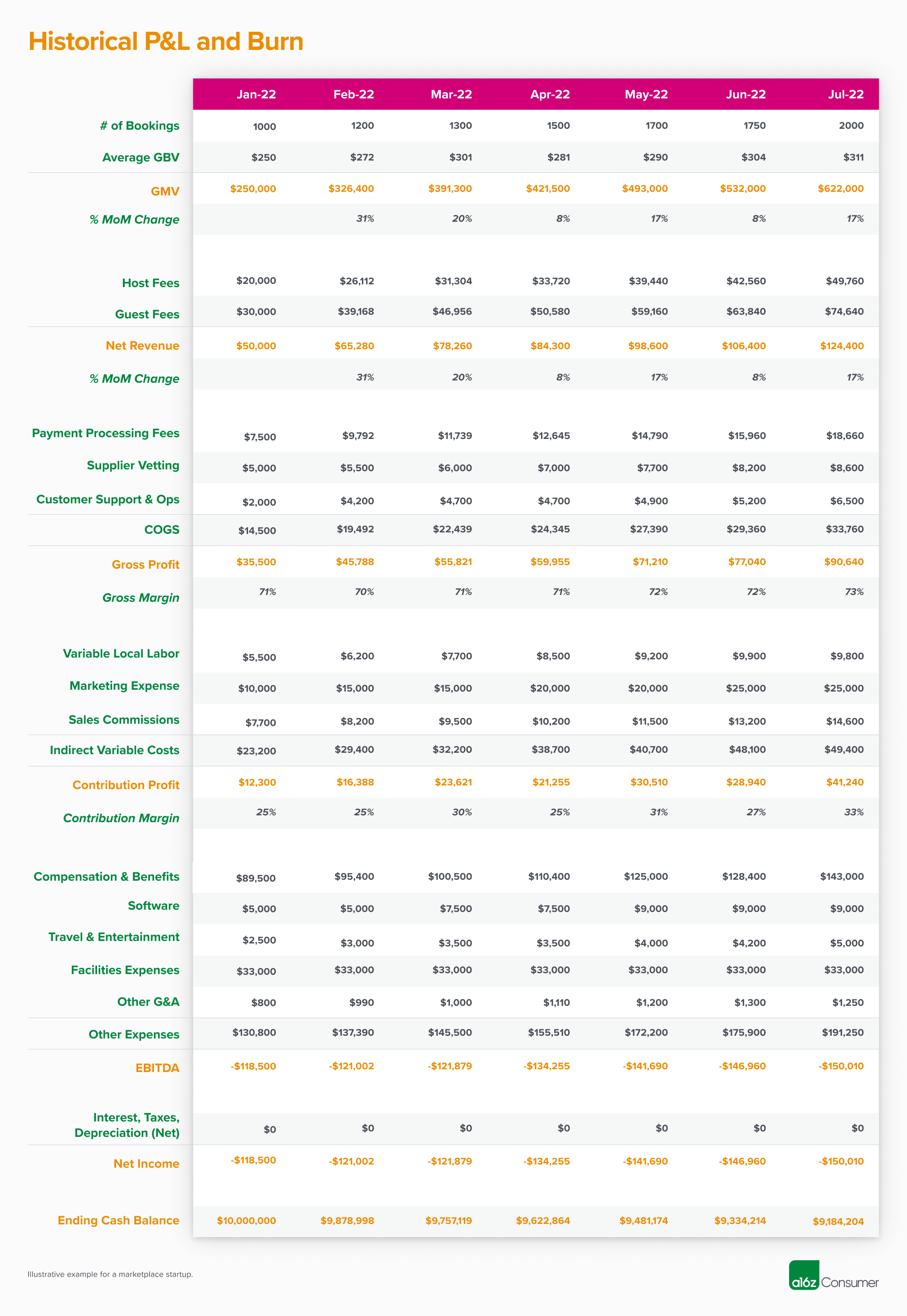

3. Historical P&L and burn. This should show the path from gross revenue through net income (loss) through cash outflow on a monthly basis. Make sure to break out different types of revenue (if applicable) and all of your major costs. It’s also helpful to add your cash balance, if you’re not including a balance sheet and cash flow statement.

4. Usage data. This data will vary based on the type of company (we’ll go into detail below on more specific metrics), but you’ll want to include data that illustrates the following:

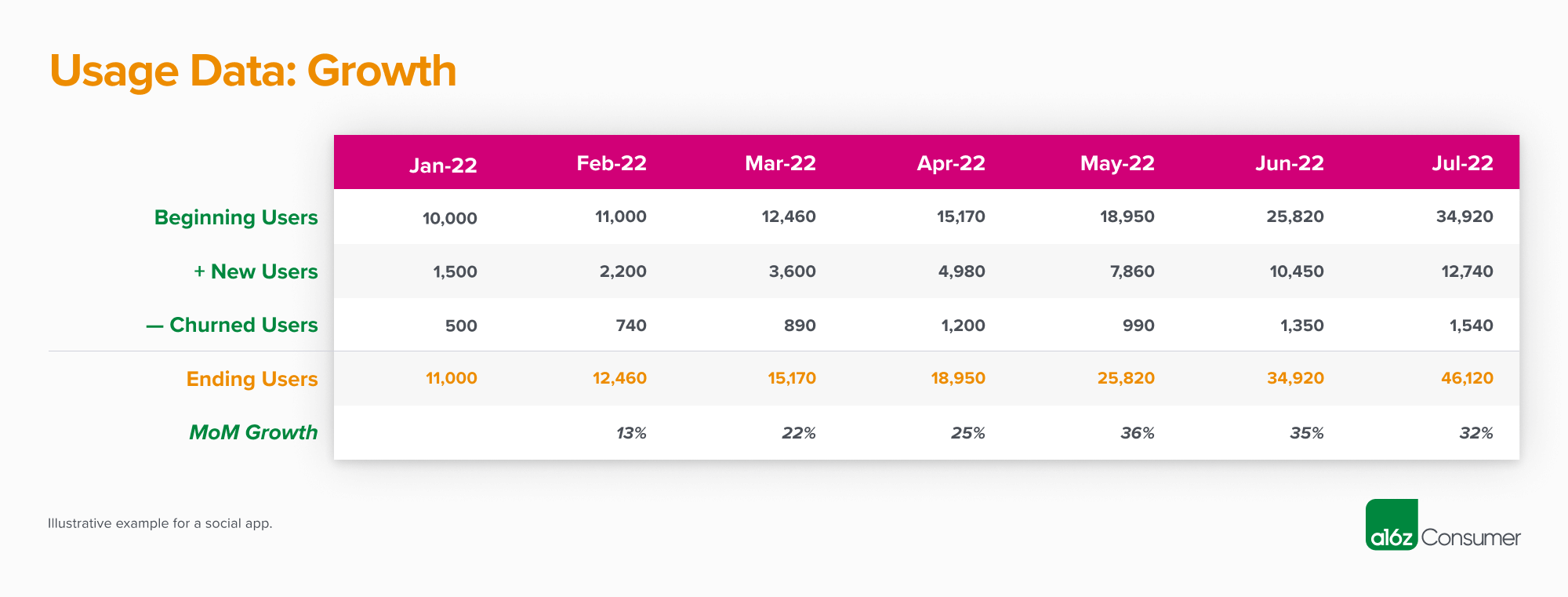

- Growth: How is your user base scaling over time, both in terms of signups and active users?

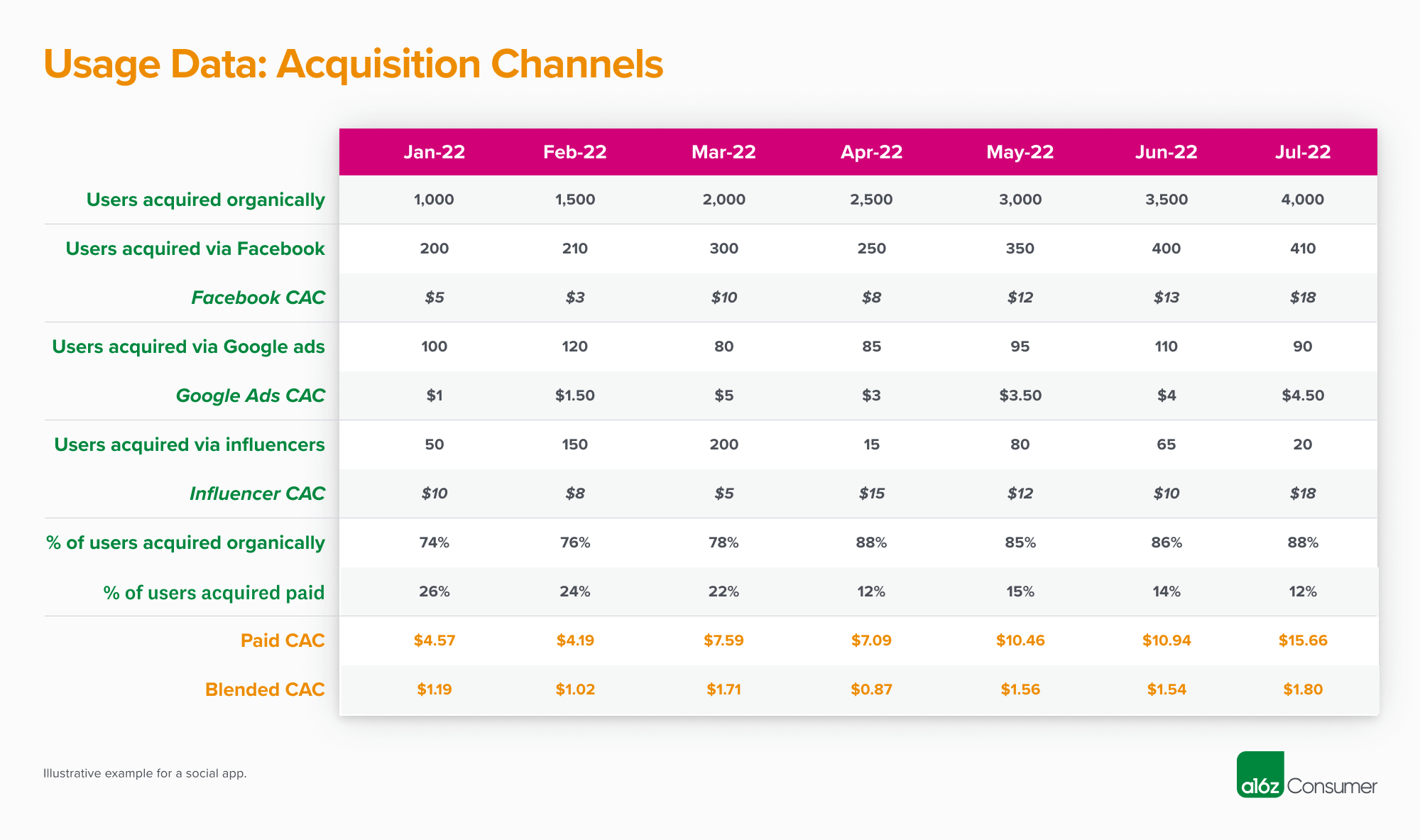

- Acquisition channels: Where are you acquiring users? How much does each of these channels cost you?

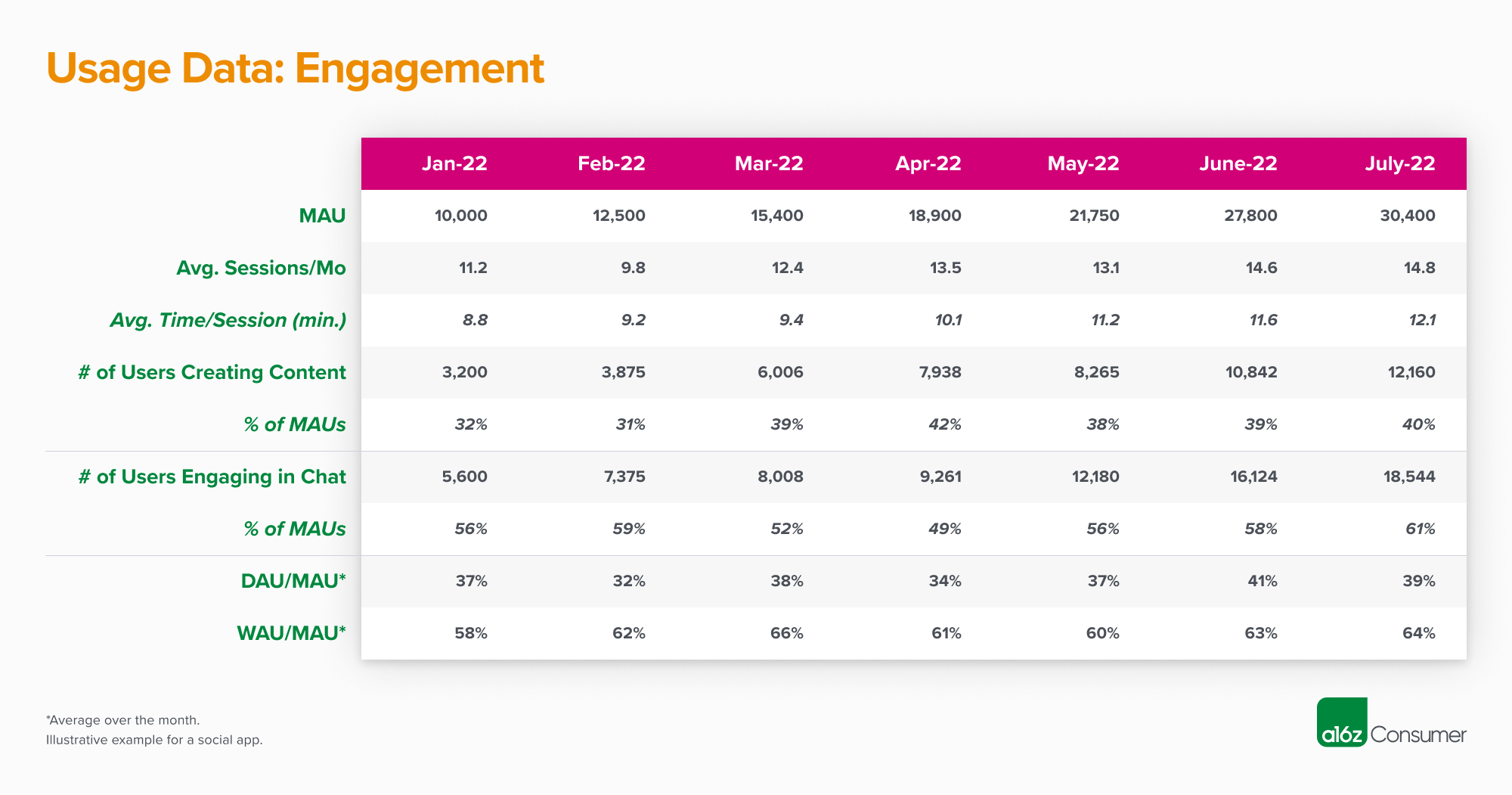

- Engagement: How often are users engaging with the product? How long do they spend on it, and what are they doing?

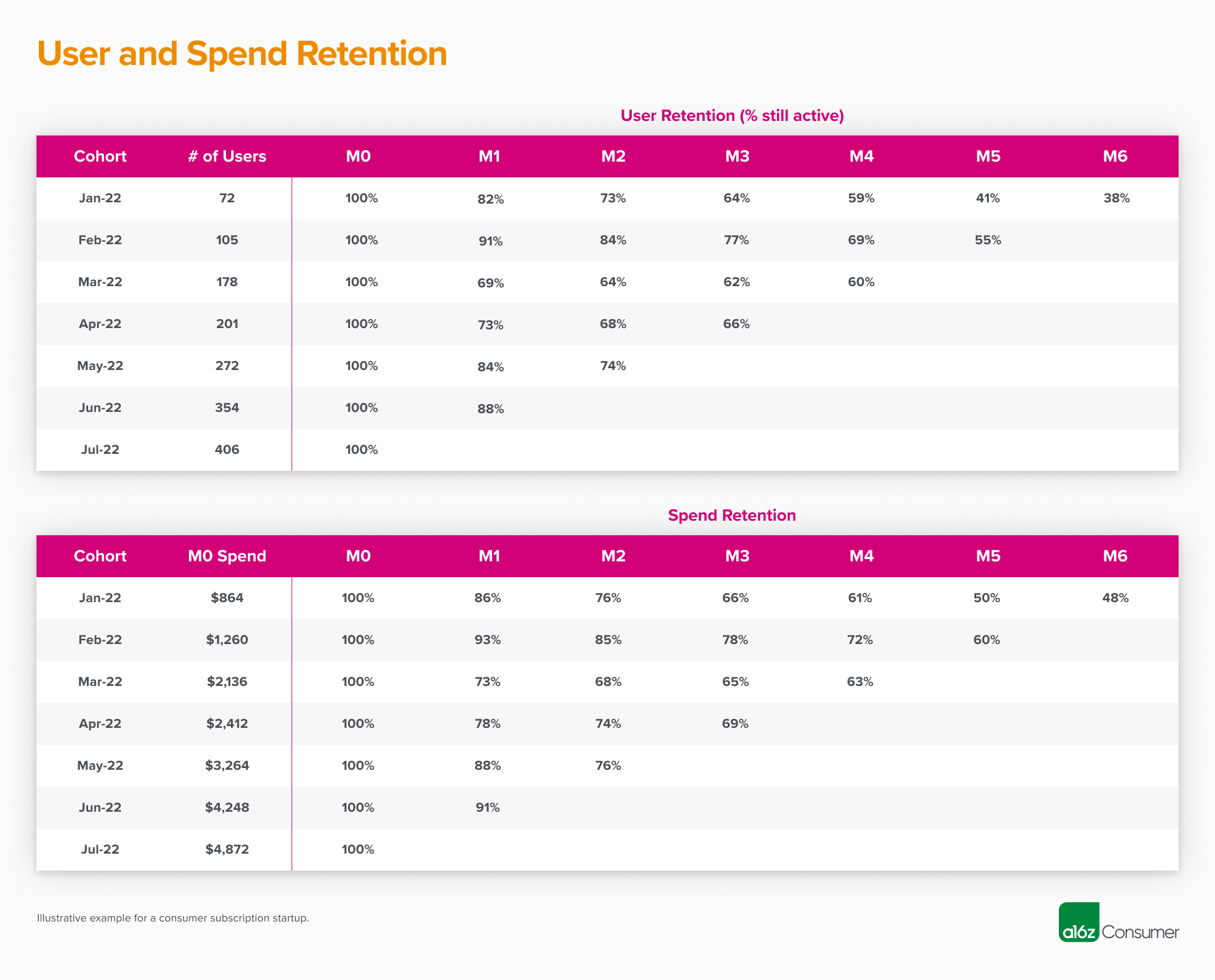

- Retention: How are users retaining over time? This usually takes the form of monthly cohorts and looks at both number of users and spend. Depending on the natural usage frequency of the product, we may also be looking for daily or weekly retention. We’ll dive into this further below for social apps.

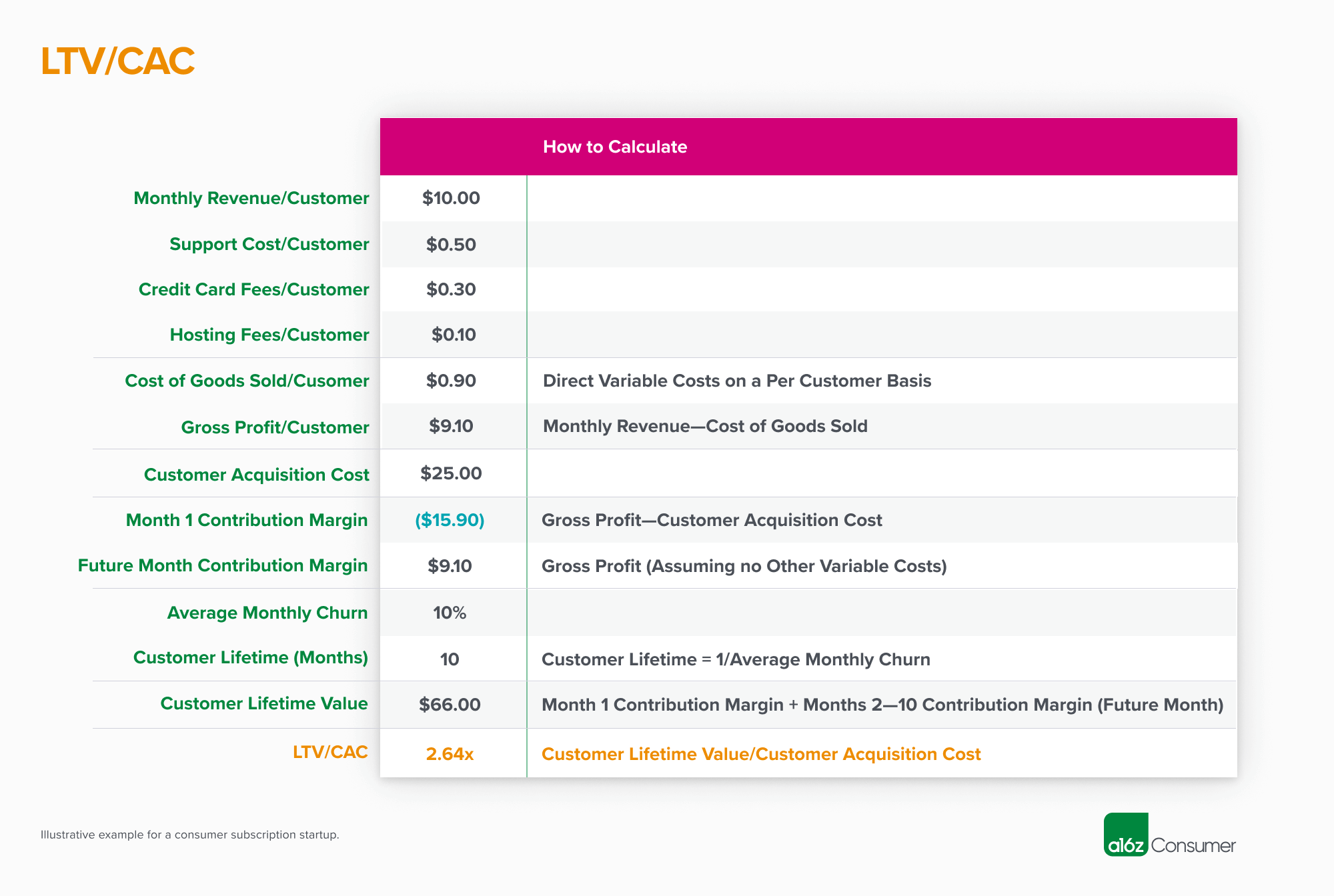

5. LTV / CAC and payback period. For many consumer companies, investors are looking for the answer to a simple question: “Are you making money on the average customer, after accounting for the costs of acquiring and serving them?” This is where LTV (lifetime value)/CAC (customer acquisition cost) comes in. LTV is a measure of contribution profit generated over the customer’s lifetime. Contribution profit is different from gross margin — it incorporates other variable costs like sales and marketing that aren’t included in COGS. An LTV/CAC > 1 indicates you’ll make money on that customer, as the profit generated by the customer exceeds the cost to acquire them.

For CAC in this equation, we recommend using blended CAC — though it can also be a valuable exercise to do with paid CAC, as it gives you a sense of whether your paid marketing efforts are profitable.

LTV is often more difficult to calculate. You’ll likely need to estimate how long a customer will retain on your product and how much they’ll spend over time. We recommend using historical data to guide these decisions, and clearly laying out your assumptions for investors to understand.

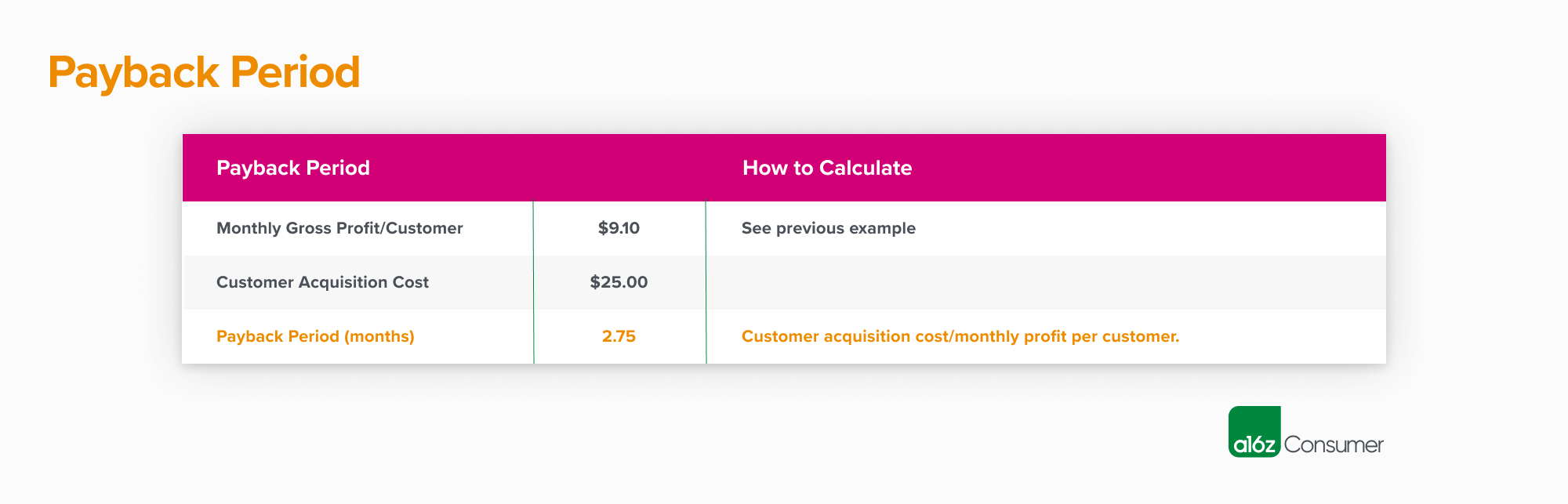

We also look at payback period, which is a measure of how long it takes for the profit generated by the customer to “pay back” the cost of acquisition. The numerator here will be customer acquisition cost. The denominator will be a measure of profit: either gross margin, assuming you have no indirect variable costs aside from sales and marketing, or contribution margin excluding sales and marketing.

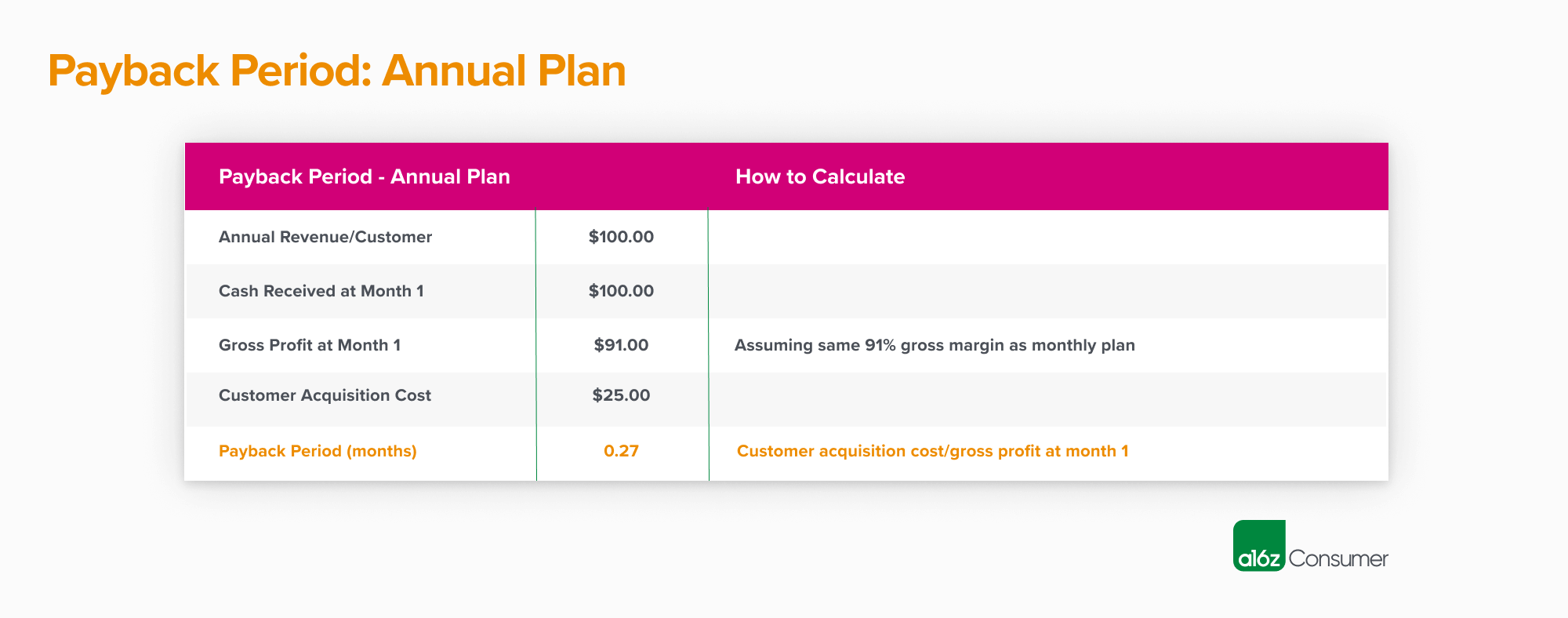

In rare cases, you may receive a cash inflow before you recognize revenue, which can shorten your payback period. The above subscription app example would look different if a customer purchased an annual plan — the upfront payment yields a payback period of <1 month.

What shouldn’t you include?

Constructing a good data room is a balancing act. You want to provide the information investors need, but you don’t want to waste your own time putting together documents or data they aren’t going to look at.

Here are five things that we often see in data rooms but wouldn’t recommend including, unless an investor specifically asks for them:

1. Org chart and/or team bios. We definitely want to understand the background of the founding team and other executives, but we generally use LinkedIn for this.

2. Detailed 3- to 5-year financial projections. This may be a controversial one, but it’s often difficult to model forward-looking financials for early stage consumer companies. We love to hear the key milestones you’re looking to hit in the coming 12-18 months (and what you’ll need to get there), but we don’t expect a fully-baked model.

3. Tax returns, audits, and legal docs like office leases or employee offer letters. We’re not lawyers or accountants! If we have a concern, we’ll request the documents we need.

4. Board meeting minutes. Unless we have a specific question, we’re generally not poring over these meeting minutes (and they tend to be heavily redacted anyway). However, we will usually take a look at board decks if they’re available.

5. Market sizing. We’ll do our own work sizing the market. There are rare cases where you may want to include this (for example, if you’re in an obscure market and it’s hard to find publicly available data).

Data rooms by category

The specific metrics that investors want to see will vary based on your business model. Below, we’ve outlined the key metrics we like to see for the categories of startup we typically look at. Keep in mind that for each of these items, investors generally want to get a sense of how they’ve changed over time (if at all), not just the current state.

Marketplaces (e.g. Airbnb, Instacart)

- Transactions, GMV, and net revenue

- Monthly new sellers and buyers added to the platform

- Active sellers and buyers

- CAC on both sides of the marketplace

- GMV retention and user retention for both buyer and seller cohorts

- GMV concentration each month in the top buyers and sellers

Social apps (e.g. Snap, Facebook)

- DAU, WAU, and MAU

- Daily retention cohorts – D1, D7, D30, D60, D90 retention

- Weekly retention cohorts – W1, W2, W3, W4, W6 retention

- Acquisition split between organic and paid users on a monthly basis, and paid CAC

- Time spent and session time per user

Subscriptions (e.g. Calm, Noom)

- Monthly active free users and paid subscribers

- MRR and gross margin

- Conversion rates for each step in the flow: install to registration to trial to paying user

- Acquisition split between organic and paid users on a monthly basis, and paid CAC

- % of users on each type of plan (e.g. monthly vs. annual)

- Monthly retention cohorts — paid user retention (% of users still paying for a subscription at X month), and active user retention (% of users still using the app at X month)

E-commerce (e.g. Cider, Rothy’s)

- Monthly web traffic, number of buyers, number of purchases, and transaction volume. (There are sub-metrics that will come out of this, like conversion rate and AOV)

- Return rate

- Customer repeat rate and frequency of re-purchases

- Gross margin and contribution margin

- % of new customers by acquisition channel

- CAC, estimated LTV, and payback period

Frequently asked questions

What if my company is pre-launch?

In this case, a data room typically includes a deck, information on your team, and a roadmap for what you’d like to accomplish before the next round. If you have a beta or have done a pilot of the product, including data on that can be helpful as well.

I never worked at an investment bank — how do I build a financial model?

That’s okay! We don’t expect founders to be Excel whizzes. Start with identifying the key drivers of value for your business. For example, that might be new users, monthly retention, and average revenue per user. Then try to project what these metrics might look like moving forward, using your historical data as a guide.

In most cases, your projections shouldn’t be vastly different from the historical data. If MAUs have grown ~20% MoM for the past six months, it’s probably unrealistic to assume 200% MoM growth for the next year. However, there are some cases where it’s reasonable to assume that your metrics will improve at scale — for example, many delivery businesses see cost per delivery fall as their network becomes denser.

On a related note, make sure that you’re fairly confident in your ability to achieve your projections. If an investor passes on your current round but wants to reconnect for later rounds, you want to be able to say that you beat or exceeded your plan.

When should I have my startup’s data room ready?

If possible, try to have your data room prepared before officially kicking off your fundraise. Putting together a data room may help you get ready to pitch investors. You’ll likely use the data in your deck, and you’ll come out of it with a better understanding of your numbers.

Having a data room ready in advance will also keep your fundraising process moving. Consider it a work-in-progress, as you’ll likely add more as you get questions from investors.

What are some red flags I should be aware of?

We don’t expect data rooms to be perfect, but there are a couple of things that may raise investors’ eyebrows:

- Numbers that aren’t consistent with what’s in the deck. For example, your deck says $2M in ARR, but your model shows $1.5M.

- Numbers that aren’t consistent across tabs or spreadsheets. One way to fix this is building one comprehensive model (instead of many different spreadsheets) and linking across tabs — so if you change a metric in one place, it changes everywhere.

- Limited historical financials. For example, you only show three months of data when your company is three years old, or you show quarterly but not monthly revenue. And make sure it’s clear where historicals end and future projections begin by highlighting projections in a different color, or adding an (A) after actuals and a (P) after projections.

- Selectively presented metrics. When you present retention or engagement data, don’t cherry-pick your best cohorts of users. Include the full data — though we also like to see “bright spots” (e.g. “Users who add 5+ friends spend 20 minutes on the app every day”).

When constructed effectively, a data room is a great opportunity to augment the story and vision behind your business with the “receipts” of what you’ve accomplished to date.