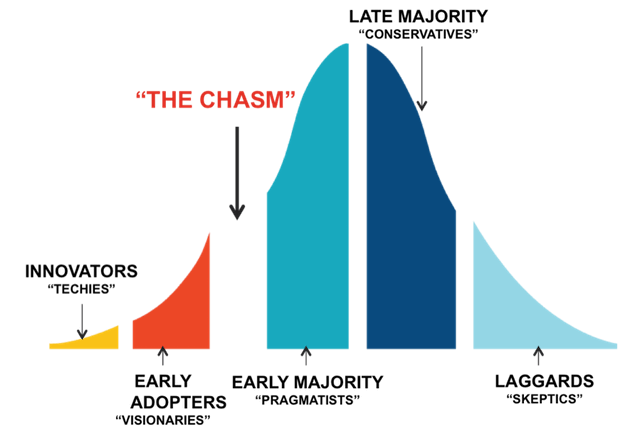

“Crossing the chasm” is a popular concept for almost all new products/startups, and is a useful lens for entrepreneurs to view the theory of innovation. The concept was first coined in the popular book title of the same name, which drew on another, earlier book about the “diffusion of innovations”. In short, both argue that there’s a gap between the “early adopters” and the “early majority” before the market for a given product matures, and until the startup crosses that chasm.

For tech founders, this model affects how to think about everything but especially how to think about sales. As the model goes, until the chasm is crossed, sales must be evangelical, sale cycles are long, and startups struggle with anemic productivity. But once the chasm is crossed, hallelujah! — those product-market fit issues are solved and the challenge now is to just keep up with demand. Because once you cross the chasm, your company goes from a difficult “push-based market” to one that is “pull-based”, where customers are naturally drawn in.

It’s a useful theory — I used it to think through my own company as well as lessons learned and shared — but in widespread practice, crossing-the-chasm almost never plays out. Worse, it gives countless startup founders the sense that it is merely a matter of time and waiting (“we’re just crossing the chasm now”) while in reality struggling to go to market for years. Moreover, given how fast technology is changing, more startups are spending more time in the chasm… and they may never exit. And guess what? That’s ok.

Sometimes even very large companies spend their entire lifecycle gutting out a push-based sale cycle all the way through IPO and beyond. Relatively young companies have been forced to introduce multiple products to navigate market shifts; others pivot into service companies; and still others go through low-margin, long, and complex sales cycles for years… and yet, can still be successful. Even in my own experience, we had to push hard into the market up to half a billion dollars in revenue and beyond. So how can you tell whether you’re in this kind of situation, and adjust board expectations and plans on growth accordingly? Below, I step through a number of examples of such situations — and assumptions — that keep companies in the fabled chasm looking for that elusive, large, pull-based market. But knowing where you are is half the battle to making it through that unending chasm.

Every new geography is a new (and often very different) market

I’ve seen a number of instances where, fueled by optimism of growth in the U.S., startups have also invested heavily in sales internationally. And then fail to produce results.

Just because a company has been able to monetize in the U.S. doesn’t mean the rest of the market is up for grabs. While this may sound obvious, entering EMEA, LATAM, or APAC is sometimes even more challenging than entering the very first market. It’s not uncommon for a company to surpass $50M revenue in the U.S. alone and still not yet crack global markets.

Often the sales leadership is blamed, but after one or two swaps of CROs, the company realizes it’s actually tackling an entirely different market, which changes how they then diagnose (and hopefully address) the issue. Is it the go-to-market strategy, or the product itself that’s causing the issue? Often it’s both: Different geographies have simultaneously different competitive environments and partner ecosystems, as well as varying pricing sensitivities and regulatory requirements that require significant product changes.

Fighting market incumbents might mean staying in the chasm indefinitely

It seems as if the competitive environment has hit a new level of treachery due to the position of the incumbents underpinning most routes to market on non-standardized platforms. In the consumer world for instance, Google and Facebook are notorious for knee-capping startups who rely on them for customer acquisition.

In the enterprise world, AWS routinely offers services that compete with its own users. Google is in the habit of trashing markets with open source. And even without these counter moves against startups, the traditional incumbents retain “account control” and a lock on the channel, which means startups are at a huge disadvantage when trying to supplant an incumbent — even if they have the better product.

All of the above means startups will face fierce and changing competition well into IPO territory, given the size of the markets relative to the size of a startup. But the whole point of this post is to argue that companies can still be successful despite never crossing the chasm, including IPO and beyond.

Markets aren’t always as large as anticipated

Another common outcome is that a startup executes very, very well and still winds up in a relatively small market. In these instances, the startup has actually crossed the chasm for that particular product, but the size of the market for said product doesn’t yield sufficiently appreciable liquidity.

These startups therefore have to enter another market chasm, by either augmenting the current offering (best case) or even introducing a second product. While this is exceptionally difficult to do — it’s tricky to figure out the if, when, and how of building more than one product in a startup — sometimes the company has no choice. Better to armor up and re-enter the battle than endure as the living dead with no route to liquidity.

Some markets will never become pull-based

It’s simply a fallacy to believe that in all cases a market matures and starts to “pull” a product rather than requiring a continued “push” from the startup.

Some products are simply difficult to sell — or “insert” — all the way to market dominance. By “insert” I mean position the product within the company doing whatever technical or educational work is required. But there are a number of ways in which product insertion can be disruptive to customers: It may, for example, require large data migration from legacy systems; or perhaps it requires a lot of custom work to tie into legacy operational environments; or worse, it requires insertion into an ongoing product- or system-development process; and so on.

Whatever the reason, a product in these markets won’t be become repeatably “easy” to sell until well after it has reached hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. If you have such a product, that’s ok. In these situations, I generally recommend leaning into services. If the product is difficult to insert, you can reduce that friction by making the work to insert the product a core competency of your startup. While margins will be impacted, and sales cycles are likely to remain long, you’ll have more control of your destiny this way. If you’re lucky, over time as the market and partner ecosystem matures, you may be able to offload the integration work to a partner.

The buyer in your market is very difficult to sell to

You know you’re in a hard, sometimes un-crossable market when it takes a lot of effort to build a business based on the ideal buyer for your product. In my experience, the two most common examples of these are: (1) non-“tech” verticals and (2) tech selling to struggling industries.

For (1) non-tech sales, many traditional verticals simply don’t know how to buy software. A common example cited for this on the consumer side is if Lyft/Uber had tried selling their software to taxi companies first; the industry simply didn’t have the ability or process to absorb the tech that would have helped them. And even when an industry does have a process for buying software, that process often doesn’t match the standard buying model most software companies are used to. Take for example state and local governments (procurement alone is a hoary beast to navigate); industries such as agriculture and mining (which are exceptionally price sensitive); etc.

To be clear, it is definitely possible to build large companies that cater to these buyers. But be aware that growth can be slower, customer acquisition cost or CAC higher, and the annual contract value (ACV) lower. There are many reasons for all this: The customer may need more education. The industry may be more price sensitive. The partner ecosystem may need a lot more education (which is often the case, and if so, they should be involved in a deal).

Another issue that crops up with these sorts of buyers is that they typically don’t have a central buyer. Even if you’re able to get a deal with the organization somewhere, you’re not able to later upsell or cross-sell, leaving you with low net-dollar retention over time. (I’ve experienced this most often selling to state and local governments.)

Finally, a common trend I’ve observed is that as (2) tech disrupts so many industries, it dramatically changes the buyer landscape, impacting all companies selling in those markets. (Common examples of this today are media and retail.)

Every time I see a startup whose primary logos come from struggling sectors, I immediately recognize that they’re going to have a harder time going to market — their customer base is under duress. Even with a compelling product that has strong ROI for those customers, the churn of a buyer undergoing disruption will be reflected in the numbers. Budgets dry up, champions leave their jobs, projects are canceled, and so on. The hardest part for founders to to accept here is that all this can happen independent of how well a startup executes on its go to market in those markets.

The point of this reality check on buyers isn’t to avoid those customers! It’s just to set your (and your board’s) expectations accordingly, keeping your valuation and burn inline with those realistic growth projections. But the courage to enter a tough market others are avoiding can sometimes be rewarded with leading the market.

* * *

It’s great if an enterprise startup manages to find product-market fit and ends up with a repeatable sales model in a large market, getting to a point where the market pulls them (and not the other way around). In that case, scaling fast is everything.

But many companies will have to bob and weave every quarter, struggling with repeatability and more. Buyers change, competitive environments change, markets end up being smaller than anticipated, the ability to monetize is more complicated than expected, insertion can be inherently tough. Furthermore, there’s more talent and money flowing into the startup ecosystem than ever before, which means good ideas get commoditized quickly and devolve into all-out execution battles that cannibalize a market before it’s mature.

Why bother then? Because it is always possible to fight your way to success, to have a shot at building something great. Most enterprise companies are built brick by (often miserable) brick. As my former board member and now partner Ben Horowitz once said it best, “There is always another move”.

So the goal of this post is to help you focus your moves, by first dispelling the myth that all successful companies cross the chasm before having meaningful outcomes. The other subtext of this post is to put a premium on survival. Seems obvious, but it’s not: The winner is often the one that simply makes it through, by being the best at weathering the transitions and anemic periods. When the opportunity to capture the market exists, step on the gas… but also be aware of the situations outlined above and adjust your assumptions — and therefore moves — accordingly.