Growing up in Seoul, Korea, I used to love shopping at the night markets, where I’d go for the thrill of the chase of a good deal. None of the items were labeled with prices, and many items could be found in multiple stalls. You point to something and watch the shopkeeper squint her eyes and size you up for a second before naming an inflated price. You feign disgust and walk away but stop a few stalls down where they have the same item and ask for their price instead. Then you pit them against each other until you reach a satisfying number and make the purchase, maybe even picking up a few more if you can squeeze out a volume-based discount.

This is the same routine many patients contemplate when they’re told they need a specific medical procedure or drug, except the chase is anything but thrilling when it’s a matter of life or death, or at least a matter of wellbeing. You’ve likely seen stories about how the same healthcare service can vary by 3000% in price, sometimes between hospitals just a few miles from each other, and the excessive behaviors of hospitals suing patients for unpaid medical bills.

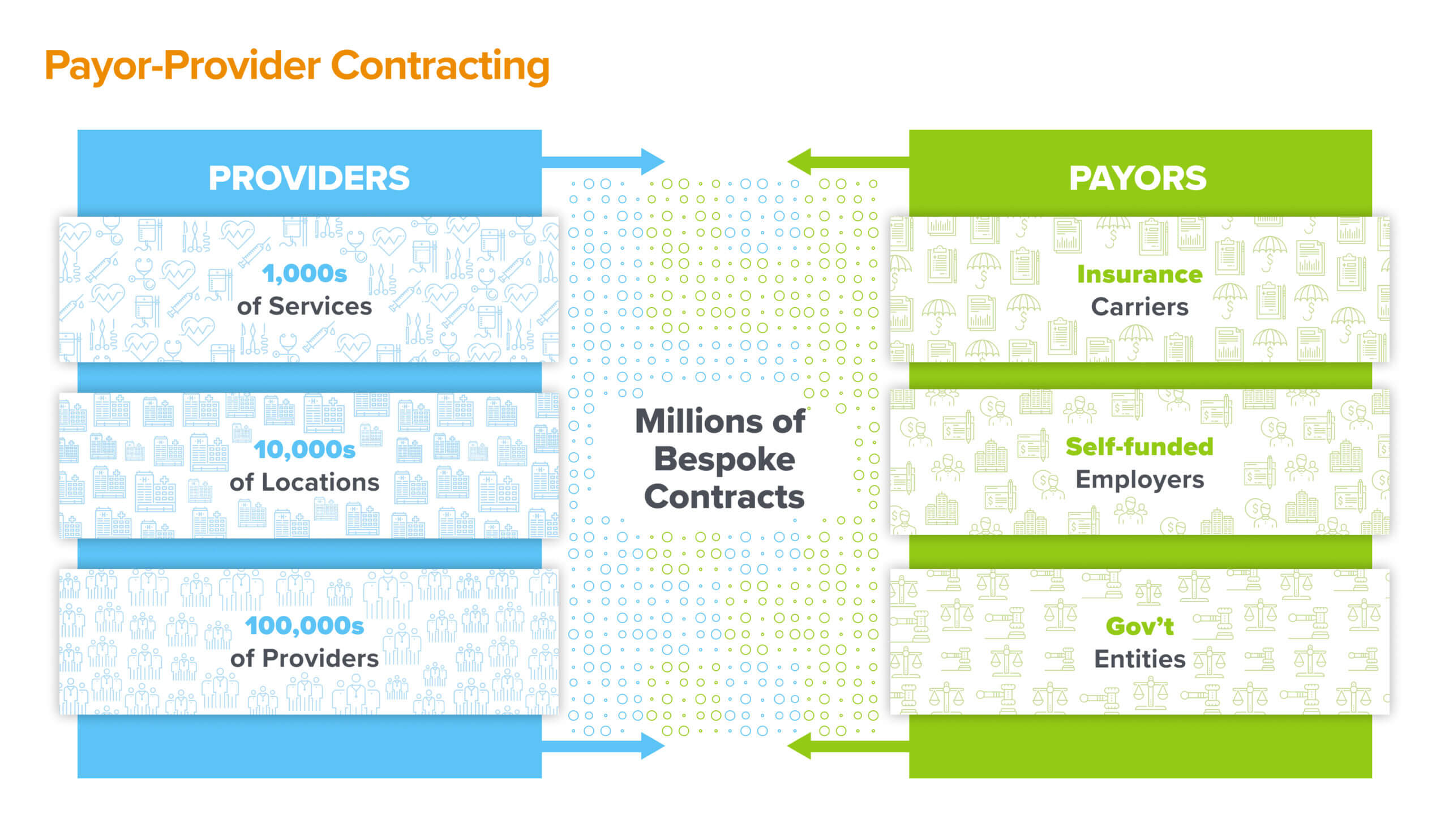

This is an artifact of our legacy payor-provider contracting system, in which the contracted rate of a given service is rarely a reflection of true underlying cost, quality, or market dynamics. Rather, they are the manifestation of the contentious balance of power between healthcare providers and insurers – with patients stuck in the middle. And since the majority of patients choose care by prioritizing two seemingly simple criteria – whether the provider accepts their insurance and what the care will cost – these payor-provider contracts end up driving most healthcare navigation decisions.

The contracts themselves are archaic and intricate. A given hospital system may have hundreds of different contracts across multiple payor entities; a given service might have over 50 different prices depending on payor product, site of care, and level of acuity. Value-based contracting only further complicates the issue. They also have numerous administrative policies embedded in them related to provider credentialing, claims submission, dispute handling, and payment terms. These high-stakes agreements are typically stored as monolithic PDF documents and fragile spreadsheets, which create significant inertia against dynamic renegotiations, repricing, and searchability of information.

As such, the CMS price transparency rules (e.g. the Hospital Price Transparency Rule and Transparency in Coverage Rule) that mandate public disclosure of contracted rates by hospitals and payors have created a massive headache for all involved due to both the technical challenges of assembling, cleaning, and systematically publishing the data and the resulting scrutiny over who is getting paid what, by whom, in what context. These rules, in addition to the No Surprises Act, have also been a forcing function for the industry to contemplate how it will systematize, scale, and ultimately industrialize the manner in which it conducts business, as it relates to reducing overall healthcare costs while improving customer experience.

Over the last few decades, the traditional markets in Seoul began to scale to larger mainstream shopping crowds through globally accessible e-commerce storefronts and distribution networks. Prices became set, transparent, and market-driven. For stores managing more than a few SKUs, it’s no longer tenable to set one-off pricing schemes or ignore competitive pricing dynamics for widely available commodity goods. Across the entire e-commerce industry, modern tech platforms have emerged to enable everything from product catalog management to bundles design, online distribution marketplaces to standardization of pricing and descriptive metadata. Retailers are now forced to differentiate based on the unique packaging of goods and tailored user experiences.

Turquoise Health is doing the same for healthcare pricing and contracting – provider organizations (health systems, medical groups, and digital health companies), payors (health plans, self-funded employers, and government entities), and even drug manufacturers are using the Turquoise platform to digitize their healthcare services catalogs and pricing, as well as assemble data-driven and modular contracts for individual services and bundles. It also automates the data collection, curation, and publication process to help payors and providers comply with their respective price transparency regulations. Ultimately, we believe that Turquoise is poised to become the system of record and B2B marketplace for payor-provider contracting that enables more intelligent, market-driven pricing practices and lays the path to transform care navigation and health experiences for patients.

We’re thrilled to continue backing Chris Severn and Adam Geitgey, the founders of Turquoise Health, by leading their Series A and supporting their efforts to create an atomic understanding of the economics of our healthcare markets at the thorny but critical intersection of payor, provider, and consumer.

***