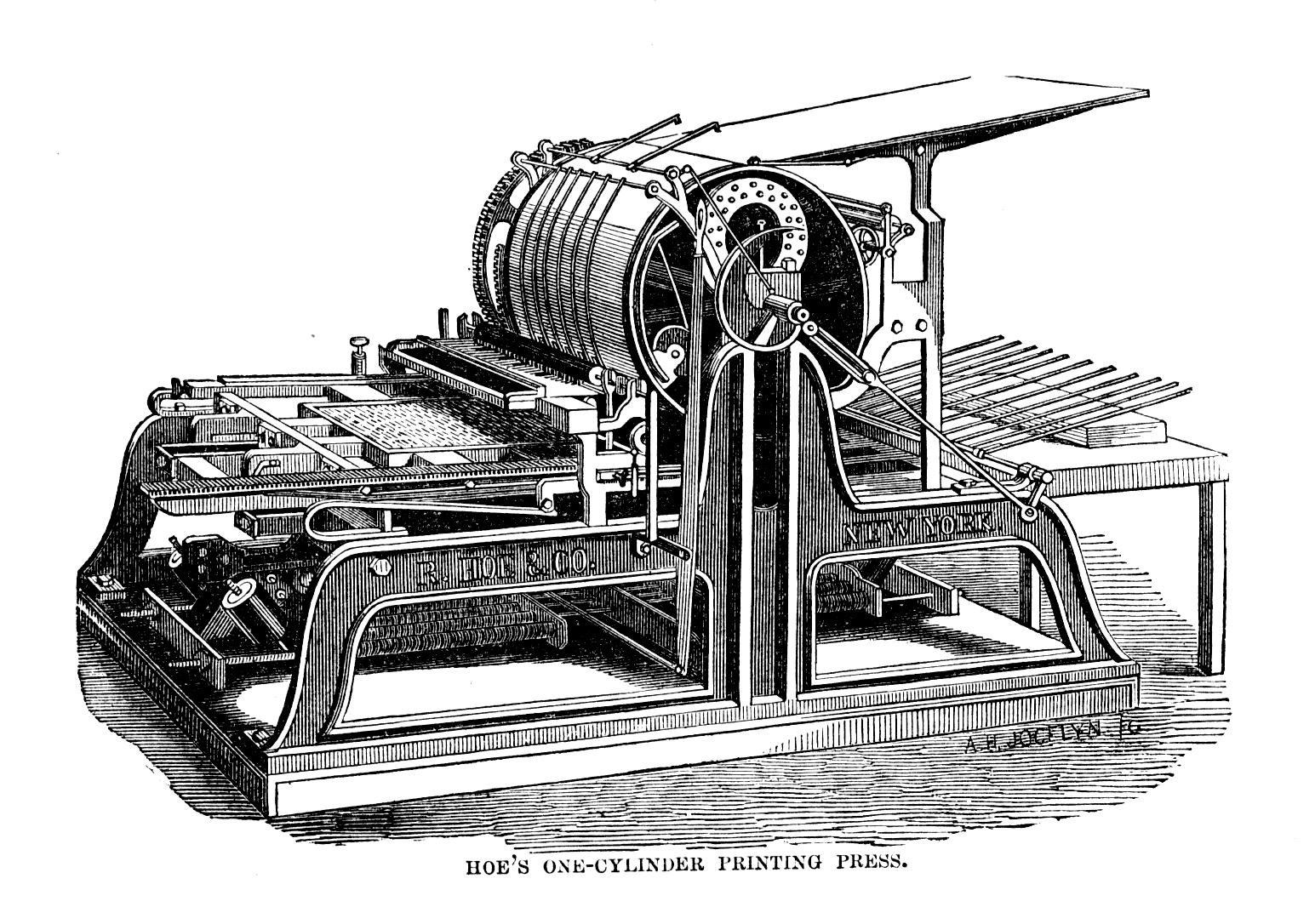

Reading — and especially writing — was once a privilege of the elite. In the medieval ages, the ability to create and distribute books was in the hands of very few: It would take weeks and even months for a scribe in a monastery to copy books, and only members of the church or nobility would then be able to read them. By the 1500s, however, technology had begun to democratize access to books and brought to light the information contained within them. The printing press not only brought books to more people, it brought more writers — philosophers, scientists, others — and other reading materials — like pamphlets, posters, newspapers, and novels — to the world, and in doing so, changed culture.

However, all this information — and the writers behind them — was still centrally distributed through the book publishers and media outlets that owned the relationship with the audience. Even though there was now a technology for creating and distributing information at scale, there was no business model for it. That is, until newspaper publisher Benjamin Day came along in the 1800s and invented a new, advertising-based model for the distribution of the written word. A newspaper cost 6 cents per issue (expensive at the time), but Day changed the economics: Charge a penny and lose money on each paper, and instead collect ad revenue on the increased circulation. The first such “penny paper,” Day’s New York Sun, was a huge success, birthing the modern media industry (and creating one of the earliest business models with multi-sided network effects). This model was quickly and widely copied. In fact, one of the Sun’s competitors, The New York Daily Times, still exists today; it just dropped the “Daily” from its name.

Since then, the internet has opened up new opportunities for media producers. A writer, streamer, or podcaster can now reach an audience of millions. Powerful tools have been created to make it easier to self-publish any format of content. Social media has allowed people to amass large followings of dedicated fans, creating a new class of jobs never thought possible: professional gamer, professional travel influencer, professional fan-fiction author, and much more.

But most of this is driven by advertising-based business models from the 1800s — the technology may have changed, yet the economic model is largely the same. And while advertising-based models will continue to be huge businesses, what if, in an alternate universe, Day’s experiment had not worked? What if individual writers had had the opportunity to figure out how to make a living selling their novellas, newspapers, and pamphlets directly to their readers?

This might not have been possible back then. But today, a direct relationship between creators and audiences can unlock a new generation of professional writers and content creators. That’s where Substack — which is building the leading subscription platform for independent writers to publish newsletters, podcasts, and more — comes in.

Substack, founded two years ago by Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi, has come along at a pivotal time in the history of mass communication — what we believe is the golden age of new media. What we love most about this age is that it can free many creatives, from all kinds of backgrounds, to pursue the type of creative work they love, and on their own terms. By “own terms” I mean making a living on your work; owning a direct relationship with your audience; and deciding how much you want to charge them for consuming your work (if you choose to)… without having to do all the hard parts.

Take my own experience: When I first moved to the Bay Area over a decade ago, I started writing a blog and newsletter that began as a journal of everything I learned while trying to break into the tech industry. In my early years, I wrote furiously, multiple times per week, while also meeting people and struggling to find my voice. But I couldn’t just focus on that part. I also had to deal with hopeless complexity in the tech stack powering all of this, from personally setting up the email list software and handling constant security issues with my content management system to custom-building welcome email sequences, figuring out and implementing SEO best practices, and experimenting with landing pages. And then, to monetize, I tried ads, affiliate links, and just about everything else. It was a hell of a lot of work for a blog that spent its first year with fewer than 100 subscribers (including my sister, my mom, and my former co-workers from my hometown of Seattle – thank you!).

I also learned a hard lesson when Google Reader shut down in 2013, and lost nearly 100,000 RSS subscribers as a result — I had to scramble to figure out how to make sure my readers and others still found me. If you really think about it, the main asset that any content creator is building up — besides the content, of course — is their relationship with their audience. Yet most writers don’t really own that relationship with their audiences; their parent media brands and other platforms do.

This is where Substack lets writers — of all kinds — directly connect with their readers. Because email is an open platform, it’s durable: It was invented almost alongside the early days of the internet, and is here to stay. It’s also portable: You can take your email addresses with you if you switch providers, offering a degree of control beyond what social media and even RSS offered in terms of audience portability (as I and many other niche content creators on the internet learned the hard way). The timeframe for building relationships over email is practically infinite; it’s not limited by how long a platform survives or switches its business model.

Most importantly, Substack handles all of the tech powering a subscription-based platform for writers to engage with — and grow — their audiences. So when Hamish first emailed me about the idea a couple years back, when I was still working at Uber, I got it right away: Substack would make it simple for anyone to focus on just their writing, instead of having to do all the other stuff I’d had to do over the years before the company existed. I began to recommend Substack to friends who were looking to start blogs or newsletters, or just wanted to share their writing in a trusted way.

I also soon began to see Substack everywhere. People were promoting it in their Twitter profiles. I heard about it at dinners from people who were using Substack to build their first newsletters and discover audiences for their words. It was amazing to see the success Substack was having, with writers well beyond the tech industry. Benjamin Day’s old competitor, The New York Times, praised it as an alternative to social media with better incentives and more reliable means of increasing readership.

So today, I’m pleased to announce that Andreessen Horowitz is leading the Series A investment in Substack, and I will be joining the board.

Talk about founder-market fit: CEO and co-founder Chris was formerly the co-founder and CTO of messaging app company Kik, where he learned firsthand how to build and scale a product used by over 300 million users. He also observed how there are sometimes tradeoffs between the incentives of users and platforms, and wondered if there was a way to positively align all those incentives so that the whole thing would get better for everyone: If more people choose to pay writers directly, more writers would join, and more readers would follow. CTO and co-founder Jairaj was a head of platform at Kik and a principal developer there who also observed firsthand the importance of incentives; he and Chris met at Kik but are from Canada, both graduates of the University of Waterloo. Last but not least, co-founder Hamish is a former journalist who has written for newspapers, magazines, and websites — as well as worked as a former freelancer (he met Chris and Jairaj doing some communications work for Kik). So he gets the exact culture of writers Substack aims to empower with their company. Hamish was also the lead writer at Tesla from 2014-2015, which led him to later write a book that Booklist described as “a must-read for everyone interested in cars, entrepreneurship, alternative energy, and deeper insights into out-of-the-box thinking, working, and living.”

As I got to better know Chris, Hamish, and Jairaj, it became clear that not only are they the right team, but that Substack can solve the structural issues between publishers/writers and readers in a way that aligns the incentives between all of them. This is the moment the next generation of media is being built, so we’re proud to be working with Substack to support the writers and creatives who already use it… and who will find and use it as the company builds even more features and tools to help their writers and readers. In just two years and with only three people, more than 50,000 subscribers now support Substack creators with millions of dollars of funding, and top writers are making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Substack not only strengthens the broader ecosystem around subscription media, but lets all kinds of writers — whether journalist, blogger, analyst — to share their thoughts and expertise with an audience where they’ve built a direct relationship. And whether that list is small or big doesn’t matter. Whereas before you needed the scale of newspaper stands and bookstores to reach your audience, now, with the internet — and a better business model — every creative can build an engaged audience at any size. Substack is pioneering a new “business model for culture”, and we’re super proud to help support them.

image: Wikimedia Commons

—