Today, about 90% of public SaaS companies and the 2019 Forbes Cloud 100 have subscription-based revenue models. Now new fintech infrastructure companies have made it possible for SaaS businesses to add financial services alongside their core software product. By adding fintech, SaaS businesses can increase revenue per customer by 2-5x* and open up new SaaS markets that previously may not have been accessible due to a smaller software market or inefficient customer acquisition.

This wave is happening first in vertical markets (meaning the market around a specific industry, such as construction or fitness). Vertical software markets tend to have winner-take-most dynamics, where the vertical SaaS business that can best serve the needs of a specific industry often becomes the dominant vertical solution and can sell both software and financial solutions to their core customer base. Moreover, while early vertical SaaS companies – Mindbody, Toast, Shopify – typically started by reselling financial services (primarily payments), they are now embedding financial products beyond payments – from loans to cards to insurance – directly into their vertical software.

In this post, we will look at why fintech is driving the next evolution of vertical SaaS, why it opens new vertical markets, and where and how different business models for fintech can be applied.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- With fintech, vertical markets are larger than most realize

- Fintech changes the CAC and LTV equation

- Embedding fintech (rather than just reselling) improves margins and makes the product stickier

- Overview of fintech models

- Fintech model: payments

- Fintech model: lending/financing

- Fintech model: cards

- Fintech model: insurance

- Fintech model: bank accounts

With fintech, vertical markets are larger than most realize

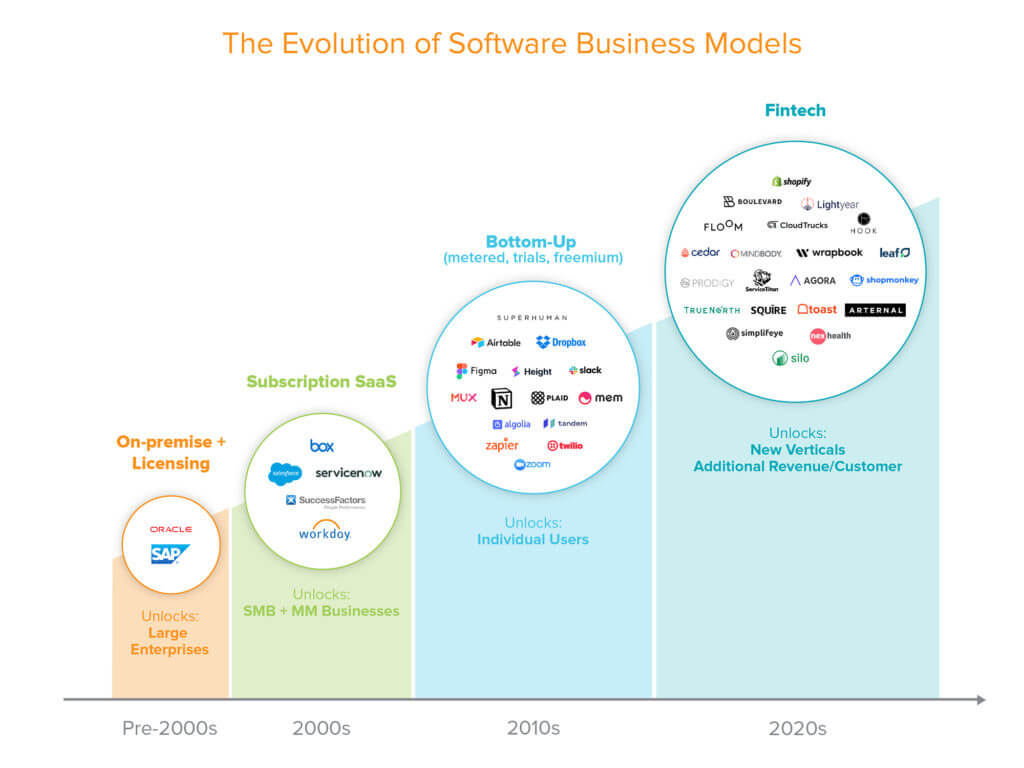

Every 10 years or so, we evolve how software is distributed and sold. Each evolution – from on-premise to subscription and bottom-up – has unlocked new markets and grown the overall software market. Until now, these software business models expanded the overall market by growing the user base, from large enterprises to small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) and midmarket companies to individual users. But the fintech business model increases the overall market for software in two additional ways:

- it increases revenue per user by 2 to 5x* versus a standalone software subscription, and as a result,

- it unlocks new verticals where previously the total addressable market (TAM) for software was too small and/or the cost of acquiring customers was too high.

Vertical markets are particularly good candidates for a SaaS+fintech business model. While customers in horizontal markets often try different software vendors, resulting in multiple winners in a market segment, customers in vertical markets prefer purpose-built software for their specific industry and use cases. Once one software solution demonstrates its value, the customer base will consolidate around that company for all its software needs. As a result, vertical SaaS businesses are able to quickly become the dominant solution in a particular industry – for example, Veeva, a CRM for pharma, has over 50% market share – and then layer on additional products (software and financial). Servicetitan began by offering software to home services businesses, but it has since layered on financial products such as payments and lending.

Let’s assume the average vertical SMB customer spends about $1,000/month on software and services. Of that, $200 per month will typically be on traditional software (e.g., ERP, CRM, accounting, marketing), and the rest on other financial services (e.g., payments, payroll, background checks, benefits). In a traditional vertical SaaS business, the only way to capture more revenue from the customer was to upsell software. This left the $800 per month potential revenue from financial services to other vendors.

But with SaaS + fintech, a vertical SaaS company can capture a customer’s traditional software spend as well as the spend on employee and financial services.

- Traditional SaaS expansion – Upsell software products or add software modules

- Fintech opportunity – Add financial services, such as payments, cards, lending, bank accounts, compliance, benefits and payroll

In our hypothetical above, a vertical SaaS company that adds, or even embeds, financial products, can potentially 5x the revenue per customer from the $200/month software spend to the full $1000/month for software and services.

Vertical markets are particularly good candidates for a SaaS+fintech business model because customers prefer one piece of purpose-built software for their specific industry and use cases.Fintech changes the CAC and LTV equation

Fintech also impacts the go-to-market channels for vertical SaaS by growing the revenue per customer and making the product stickier. Put another way: fintech holds, or even lowers, the cost of customer acquisition (CAC), while increasing the lifetime value (LTV). (Read our primer on startup metrics and acronyms.)

Mindbody, for example, earned ~$250/customer per month; while it charged ~$150/month, or ~$1800/year on average for its software plan, it earned an additional ~$100/month from payments revenue.** Thus, payments meaningfully increased the lifetime value (LTV) of the customer, while the cost of customer acquisition (CAC) remained the same, if not lower, since the additional value provided to the customer could accelerate the sale.

Lowering CAC while increasing LTV makes a direct, inside sales go-to-market possible where it previously wasn’t, meaning SaaS companies can acquire new customers that would otherwise have been too expensive. At >$5,000 average revenue per customer, vertical SaaS companies can afford to hire an outbound inside sales team instead of relying on less costly channels, like word of mouth and paid acquisition.

In fact, fintech’s potential to dramatically increase LTV means that vertical SaaS companies can offer their SaaS product for less (or even for free) to wedge into an initial customer base that may be otherwise reluctant to digitize, before layering on fintech products as the main monetization lever. For example, Silo, an operating system for wholesale food distributors, currently doesn’t charge its customers for its software, which has allowed it to successfully land customers in a market historically resistant to adopting software.

Fintech holds, or even lowers, the cost of customer acquisition (CAC), while increasing the lifetime value (LTV) in vertical SaaS.Embedding fintech (rather than just reselling) improves margins and makes the product stickier

The vertical SaaS companies who initially added financial services primarily resold financial services from a third-party. For example, Mindbody offered lending by referring customers to Lending Club.

With new fintech infrastructure players, however, companies can now go from reselling to embedding a variety of financial services, not just payments, directly into SaaS products.

Reselling remains a viable option, and can be easier to launch or used as an on-ramp to embedding financial services. However, embedding results in higher margins and a stickier product overall. It creates a more seamless customer experience: a loan through a familiar interface rather than being redirected to a third-party site. With an embedded service, the software provider can draw on a proprietary set of data – such as contractor sales to inform lending or product information for better warranties – to underwrite risk, factoring in things like seasonality to better tailor the service to each customer’s needs and risk profile. Ultimately, that produces better margins on fintech products and new go-to-market options.

With new fintech infrastructure players, companies can now go from reselling to embedding a variety of financial services, not just payments, directly into SaaS products.Fintech models: payments and beyond

While financial services can add a lot of value for customers, ultimately, a vertical SaaS company acquires and retains its customers because of its differentiated software, not the financial services it offers. In many cases, it works best to launch fintech products after customers have made the SaaS offering core to their operating system, giving the SaaS business the customer usage data to decide which fintech products add the most value.

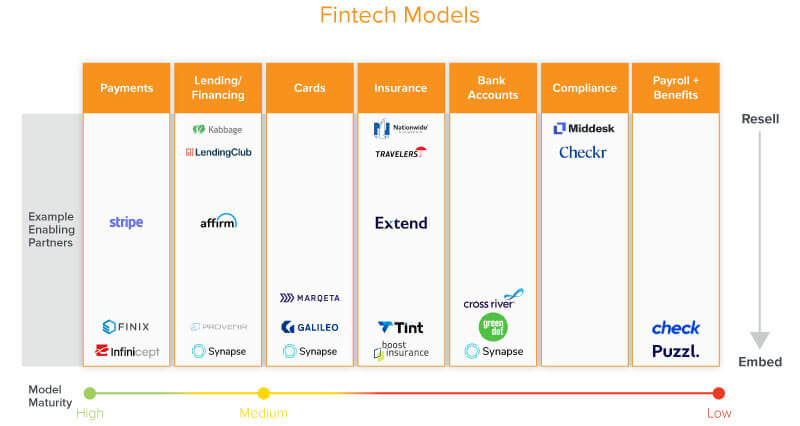

While payments are the first place that embedded fintech has emerged, and they remain an under-tapped opportunity, there are a host of embedded financial services, such as lending, cards, and commercial insurance, that go beyond payments. And we are starting to see additional services, such as payroll and benefits, emerge that can also be embedded rather than resold.

Perhaps, best of all, while payment processing is often the simplest option to add first, companies can layer financial products and services based on the needs of their vertical market. Shopify, for instance, began offering lending products to merchants because they had the data to assist with underwriting and knew that many of their merchants had to go through the painful process of securing a loan at a traditional bank.

In this section, we cover the different models that we’ve seen emerge, how each works, where it works best, what new opportunities it opens, and enabling technology partners you can leverage.

Payments

- What it is: Payment processing (e.g. enabling the business to accept credit and debit card payments from its customers)

- Referral solution: Out of the box payments processing solution for flat fee + % of transaction; SaaS business may pass through costs to its customers with a slight mark-up

- Embedded solution: Become a payment facilitator (e.g. perform merchant underwriting and onboarding, compliance, reporting etc. in house), usually with the help of other software vendors; SaaS business then has better payment economics by lowering overall costs.

- Embedded works best when: there is enough scale to justify the set-up cost, usually >$50M of gross merchandise value

Many vertical software companies have waited to monetize payments until their core business was scaling. Servicetitan, for instance, didn’t launch payments until well into tens of millions ARR. And Shopify, the prototypical example, originally launched without direct payments and primarily provided software to help small shops manage online storefronts. When it realized that merchants needed to process payments and had to go through a third-party – often a complicated and painful process, Shopify decided to leverage Stripe’s API to make it easier for merchants to manage their checkout flow.

Reselling or white labeling payments from payment service providers (PSPs) is one path. However, it can be difficult to monetize through additional mark-up fees without passing additional costs on to the customer. Companies that have made this work either have sufficient transaction volume to negotiate a better rate with their PSP (e.g., Shopify) or offer a tangible reason to transact over the platform instead of over other methods (e.g. Bill.com v. physical checks).

Other businesses, however, have embedded payments to become payment facilitators (“payfacs”) themselves. These payfacs take a more active role in processing payments and can capture 0.75-1% on the transaction volume in exchange for taking on the risks and operations associated with collecting payments.

In the same way that cloud computing services democratized the ability to launch software products, emerging infrastructure players like Finix are making it possible for SaaS companies to become payfacs. However, it still requires some scale (often ~$50-100m in gross merchandise value) before it economically makes sense to devote resources to the licenses, vetting capabilities, transaction and risk management, etc involved in becoming a payfac. Additionally, whether the SaaS business is global or U.S. only; online only or online with brick and mortar stores; or if payfac is the gateway to other financial services, such as lending, should be taken into account when deciding between reselling and embedding. becoming a payfac.

The bottom line: there is still a lot of white space for payments in vertical SaaS, and the next wave of payments in SaaS will likely see more becoming payfacs rather than reselling payments from a third-party. Additionally, many of the new software providers integrating payments will have even more complex payout flows – for instance, managing payment flows across multiple stakeholders, such as multiple contractors on a construction site or media production team.

There is still a lot of white space for payments in vertical SaaS, and the next wave of payments in SaaS will likely see more becoming payfacs rather than reselling payments from a third-party.Lending / Financing

- What it is: Loans of various types to the SaaS company’s customers (e.g., invoice factoring, 6-36 mo term loans, etc.)

- Referral solution: Link to another company that offers loans to your customer base (e.g. Mindbody referring customers to LendingClub for SMB loans); monetize by receiving a referral fee

- Embedded solution: Leverage your data to better underwrite and integrate the customer experience (e.g. Toast Capital); monetize typically by receiving % of loan value (based on risk of loan and who bears risk)

- Embedded works best when: Software company owns the transaction data needed for underwriting risk, and the category is one not well understood by a traditional bank

The loan opportunity varies greatly by type of loan, but tends to be most effective in industries with high upfront working capital and uneven spend, such as logistics / supply chain, transportation, consumer goods, food / agriculture, construction, telecom, and advanced industrial equipment customers. Vertical SaaS companies often have rich, dynamic transaction data and can understand the dynamics of the industry and customer base better than a traditional bank can. As a result, they can offer loans to businesses that were either unable to access lines of capital or tended to receive unfavorable rates – just as Shopify’s SMB customers were before Shopify began offering loans.

Historically, the primary way to offer a loan was through referral, with the SaaS companies referring customers to a lender like Kabbage or Lending Club in exchange for a referral fee. More recently, software players have started working directly with a bank partner to embed a lending program, manually managing the integration of data to underwrite and service the loan.

For example, Toast launched Toast Capital last year, to provide $5,000-$250K loans for restaurants, by partnering with WebBank. The loans are underwritten using Toast’s transaction data, making the application process faster and simpler, and repayment is automatic and adjusts based on the restaurant’s incoming cash flow, taking into account seasonality, something a traditional bank would not be able to do.

In the future, we anticipate software providers will be able to develop lending programs more easily, as today’s nascent lending-as-a-service infrastructure players mature. Whether partnering directly with a bank or building on lending-as-a-service infrastructure, monetization is typically through a profit-sharing model – the software company is more involved in the underwriting and shares some of the risk to capture a couple percentage points more of the loan value.

Cards

- What it is: Issue cards for employees or contractors of the end customer to use

- Referral solution: Referral fee

- Embedded solution: Work with card issuer to white label cards; monetize via interchange fees (% of transaction)

- Embedded works best when: Customer employees / contractors need to spend autonomously and frequently

Companies that offer virtual and physical cards have grown rapidly in recent years, with spend management software providers, like Brex, Divvy, Airbase, Teampay, and Ramp, all competing for wallet share within the high-growth technology customer segments.

Many vertical markets, however, could also benefit from virtual or physical cards. This is particularly true in industries with a large number of contractors and employees who are frequently traveling or have individual spending needs. We’re likely to see a wave of card fintech in vertical SaaS for construction, for example, so subcontractors can buy materials and tools in the field, rather than needing to spend out of pocket or wait for the general contractor to provide. There is also considerable opportunity in trucking, media, health & wellness as well, where there are contractors or a distributed workforce.

By partnering to issue cards, a vertical SaaS company can typically capture up to 1.75% on transactions, while making it easier for a finance team to monitor expenses as they happen rather than after. The infrastructure to issue cards is evolving into a mature category, with startups like Synapse and Marqeta streamlining the process.

Insurance

- What it is: Offering insurance (e.g., property insurance, workers’ compensation)

- Referral solution: Link to another company that offers insurance to your customer base; monetize via lead generation fee

- Embedded solution: Leverage your data to better underwrite insurance and improve the customer experience; monetize by receiving % of premiums sold

- Embedded works best when: Software company owns the transaction data needed for better insurance underwriting

Vertical SaaS companies can also provide insurance to their customers. For example, a SaaS company serving restaurants could provide general liability insurance insurance to its restaurant owners and worker’s comp for their employees. While all companies are mandated to buy some forms of insurance, such as worker’s comp, industries (e.g. construction, manufacturing, healthcare, media, and hospitality) that have more complexity in assessing risk, such as workplace hazards, stricter employment or legal requirements, or expensive real assets to protect will likely most appreciate a vertical SaaS solution.

Data collected by the vertical SaaS company can assist in underwriting – for instance, using restaurant reviews and other data to better underwrite workers compensation risk, or customer data to better price warranties. In the early days, we anticipate that referral fees will continue to be the primary mode of monetization, but eventually as SaaS platforms embed insurance, they could get a percentage of insurance premium sold.

Bank Accounts

- What it is: End customers can create transactional accounts to hold money

- Referral solution: Not common

- Embedded solution: Leverage platform’s data to better underwrite and integrate to the customer experience; monetize through flat monthly fee and/or interest sharing

- Embedded works best when: Customers transact (both depositing and spending) frequently enough on the software platform to merit opening an account

Bank accounts make sense if end customers are both collecting and making frequent payments via the platform and would benefit from a place to maintain a balance for those funds, rather than making constant bank transfers. Usually payments come first, and then bank accounts help manage the inflow of payments. This works particularly well in service industries (e.g., restaurants, hospitality, health / wellness / beauty) and e-commerce.

Bank accounts can be enabled through some partners (e.g. Synapse, GreenDot), with more banking-as-a-service providers emerging. Earlier this year, Shopify announced that it would launch Balance bank accounts, one of the first companies to offer this product. The bank accounts allow their merchants to easily collect frequent payments and also pay for Shopify services through one account, without needing to leave Shopify’s software and waiting for bank transfer times.

Other Services

Below are a number of other services that a vertical SaaS customer is already using or offering, but that the SaaS company can provide more seamlessly. Overall, these services are far less mature than financial services, and today, vertical software companies are simply resellers who refer customers to third-party services for a fee. However, we anticipate that shifting more towards embedded services, as more infrastructure providers emerge.

- Payroll / taxes – This is compelling in industries where work or pay is irregular, such as contractor or project-based work, and payment is based on percent completed rather than a fixed salary. This includes professional services (e.g. accounting, legal, and finance) as well as creative industries (e.g.media). Additionally, industries that rely on freelancers and cross-border employees (e.g., design, engineering, customer support) often have complex tax implications that require an industry-specific solution.

- Compliance – Background checks are one potential option. This could be a fit for industries with frequent hiring (e.g., retail, restaurants, health / wellness / beauty, construction), or with agents that require periodic credential verification (e.g., insurance). Another opportunity in compliance includes KYC (know-your-customer) checks.

- Benefits – This could be most beneficial in industries, where benefits (e.g. health insurance, retirement savings plans) have typically been difficult to provide, perhaps due to contractors or time-bound work that needs limited-duration benefits that traditional providers do not offer.

It’s just the beginning…

Fintech is unlocking a new era for vertical SaaS, where the majority of revenue comes from financial services. As SaaS companies add financial services, they not only increase revenue per customer (often by 2-5x), but they open opportunities in markets previously deemed too small, or not cost efficient to acquire customers, to be viable.

And this is just the beginning. As more companies incorporate financial services into their SaaS offerings, we look forward to seeing more markets open, and to backing the next generation of companies that will scale to even greater heights.

As investors, we are excited to combine SaaS + fintech expertise to help the next generation of vertical software businesses to realize their enormous potential.

—

*How did we calculate this? Market research and conversations with vertical SaaS companies. In our conversations, most vertical SaaS companies charge between $50 and $1,000 per month for software ($200 per month is a commonly accepted price point), and most end customers in vertical markets spend $500 to $1,500 per month on software and services (which we’ve averaged to $1,000 per month). Consequently, there’s around a 2-5x larger market opportunity when expanding out from just the software portion alone.

**Source: https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2018/11/06/mindbody-inc-mb-q3-2018-earnings-conference-call-t.aspx

Photo by Morning Brew on Unsplash

-

Kristina Shen is a former General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz where she focused on enterprise and SaaS investing.

-

Kimberly Tan is an investing partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on SaaS and AI investments.

-

Seema Amble is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on investments in B2B software and fintech.

-

Angela Strange is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on financial services, insurance, and B2B software (with AI).