Dell recently announced an agreement to acquire EMC [NYSE: EMC] — and with it, control of VMware [NYSE: VMW] — in a deal valued at $67 billion at the time of the announcement.

While analyses of the deal so far have been devoted to the (more straightforward) implications for the computing, storage, and networking industries or the (less straightforward) financing of the transaction, analyzing these threads together reveals a far more interesting story:

This is the first, big, over $50 billion transformative deal that we believe points the way to the future of many large public incumbent technology companies.

Many tech industry incumbents are stalling — in revenue growth, in investor interest, in strategic position — and something has to give. This deal is a new way for something to give.

How Dell and EMC put this deal together is interesting, as a lot of experts thought a buyout deal of this size could never happen — and certainly not in technology. The sheer size as a leveraged buyout is unprecedented. The amount of debt used to finance the deal is staggering. And all three companies involved were already incredibly complex — not just in their organizational and business structures, but in their ownership and capital structures as well.

So pulling the deal apart is a bit like opening a set of Russian nesting dolls, backwards: starting from the smallest detail to work our way outwards to the surface and current story…

The financial details of the deal

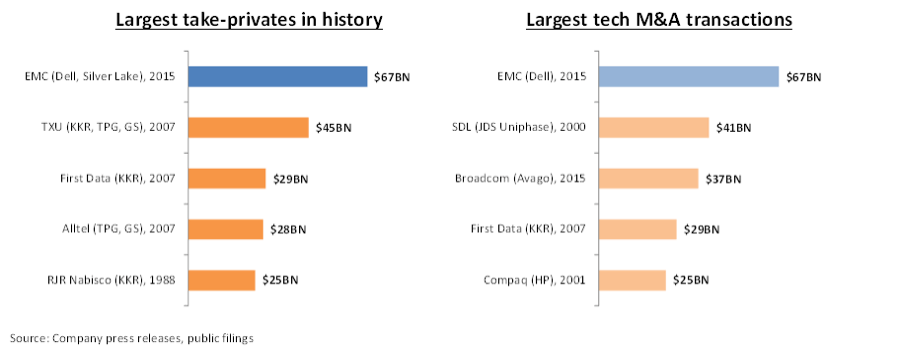

For those who don’t closely follow mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity, the Dell-EMC deal represents many superlatives:

* It’s the largest take-private in the history of buyouts — bumping from the top-five list Dell’s own $24B take-private transaction.

* It’s the largest technology acquisition in history — and the largest North American M&A deal in any sector this year, even amidst many other large M&A deals.

* It represents the largest financing commitment for a technology deal ever, with up to $50B in debt — more than twice as large as any previous deal in history.

The debt component of this deal is particularly dramatic. Because how else can the smaller python eat the much larger cow? Put in transaction terms, just how do you pull off financing a $67B deal with $4.25B in cash?

That is the (63) billion dollar question! We need to understand how EMC shareholders will receive, as announced, “a total combined consideration of” $33.15 per share [note, this is now $30.51 as of Friday’s close] with approximately 2B diluted shares outstanding.

It’s certainly possible that the combined Dell-EMC entity could sell assets to generate additional cash in the future, including anything from a partial sale of VMware (easiest to do as it is already publicly traded) or an IPO of Dell’s security business Secureworks (rumored to be on confidential file with the SEC for an offering worth $1B at the low end) to publicly floating Pivotal sooner than later (already expected to IPO at some point). But even though some asset sales are likely in the future, Dell-EMC management believes EMC will retain its federation-like structure.

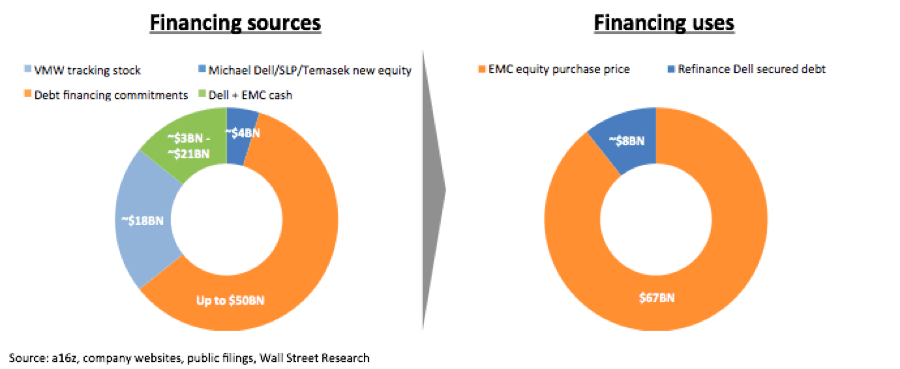

For now, the short answer is that Dell plans to fund the deal through a combination of (1) stock, (2) new equity, (3) debt, and (4) existing cash. We’ve attempted to simplify and show the proposed financing sources and uses below:

Think of the sources of these funds as a bit like a recipe — only one where you have wiggle room for how much you need of each ingredient, depending on how much you have stored in the kitchen cupboard.

The ingredients of the $67B deal — the $33.15 per share at the time of announcement — that EMC shareholders are to receive break down as follows:

(1) Tracking stock worth $9.10 per share in value at the time of announcement [note, this is $6.46 as of Friday’s close], which will be “linked to a portion of EMC’s economic interest in the VMware business”. This is a new (for VMware) class of stock that, as defined by the SEC, “tracks” based on the financial performance of a company division. More specifically, existing EMC shareholders are expected to receive 0.111 shares of new VMware tracking stock for each EMC share. (We share more on the implications of a tracking stock later.)

(2) New equity coming from Michael Dell and his personal investment firm MSD Capital, Silver Lake Partners, and Temasek, who together are contributing $4.25B — approximately $2.11 per share.

(3) Debt coming via Dell, which has lined up $49.5B in commitments (!). This committed debt will, according to management, later be paid down aggressively by the combined company’s cash flow and will be used to pay EMC shareholders for their shares (less the $8B that will be used to refinance Dell’s existing debt load). Exactly how much combined debt and existing cash (discussed below) Dell will use to fund the transaction hasn’t been specified yet and is subject to change. But the total amount will reflect $21.94 per share in value (to recap so far, that’s what’s left of the $33.15 in total consideration after subtracting the $9.10 in tracking stock and $2.11 in new equity).

(4) Existing cash that both EMC and Dell have on their balance sheets, from $3–$21B. That’s a huge range, and how much more or less cash the companies end up using for the deal is important. It has implications not only for how much debt needs to be raised, but for how much cash a combined Dell and EMC need to run their businesses day-to-day; how well capitalized the business will be to make investments and acquisitions after the deal closes; and how much the new Dell-EMC will need to rely on future cash flow to pay down remaining debt. According to the investment bank Jefferies, Dell and EMC will initially need about $6B of cash to run the business, so any excess cash can be used to finance this transaction. Jefferies’ research also suggests a fairly aggressive debt/EBITDA ratio: 4.1x–6.0x (3.1x–4.4x net EBITDA), which makes the cash aspect of the deal a balancing act between reducing debt right now versus over time… while also trying to build a newly combined business.

This is quite a tightrope walk between leverage and opportunity! But going back to the entire premise of this post, something had to give for EMC. And this deal — complex though it may be — is a new, albeit dramatic, way for a big public company facing stiff headwinds to give itself the flexibility to operate more freely.

Ironically, though, the larger “public” company here (EMC) is the one going private; the smaller “private” company here (Dell) is the one going public, sort of (assuming they will be an SEC filer with public debt); and, they’re both doing so at the exact same time. For dealmakers, it just doesn’t get any more creative than this.

But who are Dell and EMC, really? Understanding this seemingly angsty question reveals both the acrobatic contortions the companies had to go through while on the tightrope to put this deal together, as well as the assets and potential synergies of the combined entity.

The organizational details of the deal

Who is Michael Dell? He is both an investor (through his initialed private investment firm MSD Capital — the lead investor in both the Dell and EMC take-privates) and an entrepreneur who literally started Dell out of his college dorm room. The company grew rapidly selling consumer and small business PCs initially and then expanded to selling to large enterprises as well. Of the $56.9B in revenue the company generated in 2013, only half was from client computing devices like PCs — the remaining revenue came from selling servers, networking, and storage hardware (19%); third-party software and peripherals (16%); and services (15%). In its mature state, Dell had become a full-spectrum provider of technology and services to consumers, small businesses, and enterprises.

However, as buyers began favoring cheaper commodity hardware and the shift to mobile and cloud kicked in, Dell began seeing sales decline in every category except for its server and networking businesses:

The company — which initially went public in 1988 — needed to restructure its business to adapt to these changing industry conditions. But it found that onerous to do under the quarterly scrutiny of the public markets.

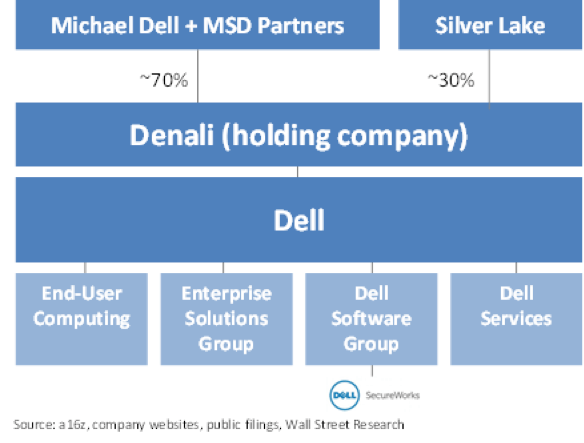

So, in 2013, after a tussle with shareholders, Michael Dell announced that Silver Lake Partners and MSD Capital would finance a take-private of the company, delisting it from Nasdaq and allowing it to operate once again as a private company.

So, in 2013, after a tussle with shareholders, Michael Dell announced that Silver Lake Partners and MSD Capital would finance a take-private of the company, delisting it from Nasdaq and allowing it to operate once again as a private company.

EMC Corp., meanwhile, which was founded a decade earlier in Boston by Richard Egan and Roger Marino, went on to become a global leader in storage, security, virtualization, and cloud computing solutions to the enterprise — with over $24B in revenue.

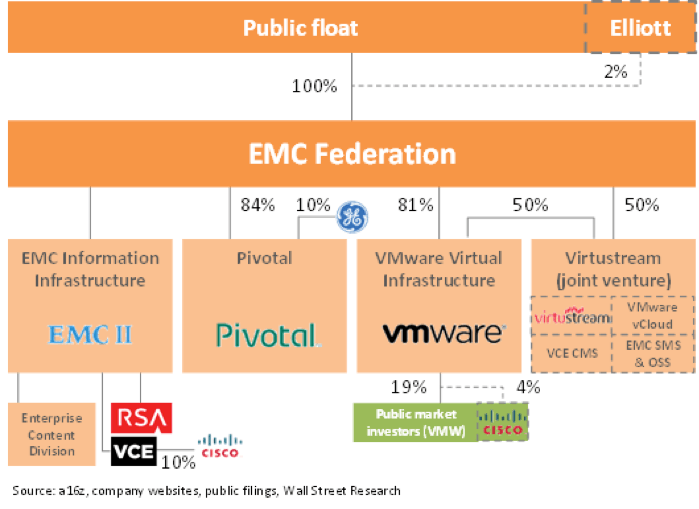

Last year, it was revealed that activist hedge fund Elliott Management had built up a ~2% stake in EMC — making it one of the company’s largest shareholders.

EMC operates as four federated lines of business: (1) EMC Information Infrastructure; (2) Pivotal; (3) VMware Virtual Infrastructure; and (4) the just-announced Virtustream unit. Let’s look at what each of these businesses do (based partly on EMC’s annual financial reports), to shed light on why they matter to Dell:

EMC Information Infrastructure, EMC’s core business line, offers a full-stack family of high-end and midrange storage systems and software solutions to the enterprise — including flash optimized storage, unified backup and recovery, storage-area networks (SAN), networked-attached storage (NAS), unified storage combining NAS and SAN, object storage, and/or direct-attached storage environments. The storage business alone has over $16B in revenue. Business units within EMC II include the:

Enterprise Content Division (formerly known as Information Intelligence), which came out of EMC’s $1.7B acquisition of Documentum in 2003. It provides document management solutions to the enterprise including capture, management, archiving, governance, and compliance. As data continues to grow in large enterprises, this is a very complementary, “sticky” business to EMC’s main storage business.

RSA Information Security division offers identity and data protection, security management and compliance, and security operations. In 2014, EMC bolstered its security solution by introducing the Advanced Security Operations Center (ASOC), an integrated set of technologies and services designed to help organizations identify threats before a breach can occur.

VCE, which was formed by Cisco and EMC in 2009 with investments from VMware and Intel; EMC subsequently acquired 90% of VCE in December 2014. VCE helps enterprises accelerate cloud adoption and reduce IT costs through converged infrastructure. It’s a way for organizations to centrally manage IT and quickly stand up a private cloud.

Pivotal, which was formed by EMC and VMware in 2013 (along with a $105M investment from General Electric), a joint venture designed to spin out some of EMC’s cloud computing solutions. These include platform as a service, agile software development services, and big data solutions such as enterprise data warehousing, database engine, and in-memory data grid.

VMware, the virtualization solutions company co-founded in 1998 by legendary Silicon Valley entrepreneur Diane Greene along with others; it is currently about 81% owned by EMC (more on this later). VMware’s virtualization offerings — hybrid cloud computing, end-user computing, and software-defined data center solutions — are important since they allow businesses to run and consolidate multiple operating systems and applications on a single server box, resulting in resource efficiencies and greater economies of scale. This was a significant technology platform shift from the previous model, where a different expensive server would have been dedicated to every single different application.

Virtustream, a cloud management company that EMC purchased earlier this year for $1.2B, which will now be spun out as its own unit operating independently under EMC while being half owned by EMC and half owned by VMware. Its financials will be consolidated into VMware’s results. The Virtustream unit will, according to their announcement, align with both EMC and VMware’s existing cloud capabilities to “complete the spectrum” of both on- and off-premise offerings — something that they argue will create “the industry’s most comprehensive hybrid cloud portfolio”. Management expects the business to deliver several hundred millions dollars in revenue by 2016 and to become a formidable competitor to other cloud infrastructure-as-a-service players.

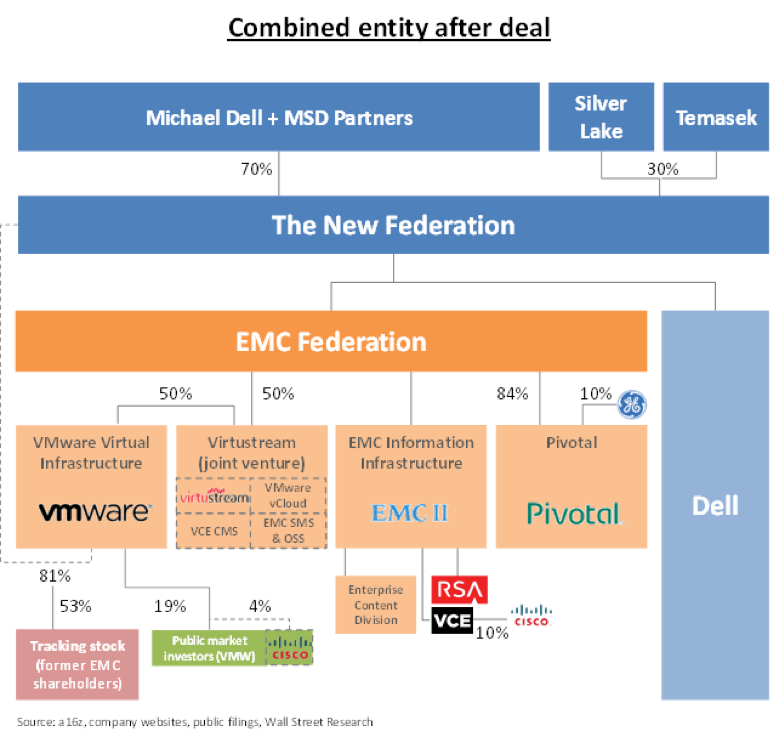

Putting all these organizational pieces together, the new Dell + EMC will look like the following:

But the bigger question is, does 1 + 1 = 2 … or 3? Is the sum of the whole greater than the solo parts? This, too, is the $67B question — particularly given how much debt, as outlined above, is being used to finance the deal.

Does 1 + 1 = 3?

A core assumption of the deal is that by marrying two (and with VMware, three) largely complementary franchises — which have an enormous installed base and market share — the combined company should generate both strong and stable cash flows. Management has also stated that they expect more than just cost savings as they combine the companies and remove duplicative functions: They expect significant revenue synergies from cross-selling solutions to each business’s customer base. Those revenue synergies are expected to be three times as large as cost synergies, pointing to over $1B in potential additional annual revenue. If true, this would imply ~$300M in potential cost synergies in addition to EMC’s existing restructuring plan to achieve $850M of cost savings.

An unexpected benefit of the deal — given the heavy reliance on debt to fund this transaction — is an improved credit profile. As Moody’s was quick to point out, the enormous cash-flow generation of the combined entity (as well as Dell management’s track record of aggressively paying down debt after its own take-private) will result in a more favorable credit position after the transaction closes. Assuming, of course, the successful execution of the rarely used tracking stock structure to finance part of the transaction.

Also important to note here is that in the last 12 months, EMC has spent $4.6B on dividends and stock buybacks, and VMware spent an additional $700M on stock buybacks … all of which will go away after this transaction. Let that soak in for a moment: Dell will spend less on the annual financing cost (interest expense and principal payments) of the $49.5 billion in debt used to purchase EMC, than EMC did on equity dividends and share buybacks in the last 12 months.

For Dell, the key drivers for the deal that could be really transformative for them include:

…complementary products and scale. Besides the obvious marriage between Dell and EMC’s combined hardware stack with VMware’s virtualization software, only IBM will be larger in revenue across the entire storage, server, networking, and virtualization landscape after the HP split is finalized next month.

…extending its franchise into large enterprises. While Dell broadened its reach beyond consumers and small businesses to mid-size enterprise, it never fully staked its claim up-market. The addition of EMC and VMware gives Dell a strong footing in the large enterprise segment with a combined 28% of the worldwide enterprise storage market.

…a powerful enterprise salesforce. Most notably, the combined company will have a strong enterprise salesforce covering all the segments. Whether it remains siloed or integrates across product lines to cross-sell and upsell offerings, the fact remains that a very strong salesforce — especially an enterprise- and cloud computing-savvy one — is hard to find. These products do not sell themselves, and as anyone who has done enterprise sales knows, taking down big deals is like getting a bill passed in Congress.

Of course, the combined Dell-EMC entity could just end up as a bigger version of the same companies in the same industry facing the same stiff headwinds. But beyond the opportunity for synergies, VMware gives Dell — previously hamstrung for such growth — optionality for the future. And that’s the key here.

VMware: The key chess piece

One of the most notable aspects of the Dell-EMC deal is VMware — not just for obvious technological reasons but for transactional reasons as well — specifically, the use of VMware stock to effectively “pay” for a big part of the deal. This indicates the creativity/contortions/convolutions (however you want to look at it!) required for large public companies to make structural changes to themselves in today’s environment.

But the inclusion of VMware in the deal raises more questions than it answers, so here’s our attempt at explaining what’s happening:

Wait, so who owns VMware now?

EMC currently owns 81% of VMware, which equals 343M VMW shares. Those shares will get used as follows:

* Approximately 120M VMware shares will be retained by Dell for 28% VMware economic interest.

* Approximately 223M VMware tracking stock shares, representing 53% VMware economic interest, will be issued to EMC shareholders.

When the deal is complete, Dell will have full operational control of VMware with 97% voting rights (due to VMware’s dual-class stock thanks to EMC), even though it will directly own only a 28% economic interest.

Put another way, Dell will continue to own and control EMC’s 81% interest in VMware, although Dell will only retain direct economic interest in 28% of VMware after accounting for the tracking stock. Existing VMware public shareholders will retain the 19% VMware ownership they owned before the deal, along with their current 3% voting rights.

Overseeing the new VMware tracking stock will be the Dell Board and a three-person “Capital Stock Committee” that will be composed of at least two independent members.

Sound complex? It is!

What does it even mean to own ‘tracking stock’ in VMware?

Tracking stock, by definition, is stock that is intended to reflect the performance of an underlying business unit — in this case, VMware — and thus represents an economic interest in that business only. Tracking stock shares do not represent underlying equity ownership, associated shareholder voting rights, or other control.

The fact that existing EMC investors will receive tracking stock in VMware as part of the transaction is unusual, and not just because tracking stocks typically trade at a discount to actual equity shares (one analyst at Susquehanna projects a 5% to 10% discount for VMware tracking stock compared to normal VMware stock, due to the lack of voting rights).

Tracking stock is unusual because it’s rarely used today — even though it was common in the 1990s and early 2000s, with mixed results: For example, for the wireless units of large telecom companies like Sprint and AT&T; the digital divisions of large companies like Disney; and unique divisions in companies like Genzyme and Circuit City. The only notable example of a tracking stock structure used today is Liberty Interactive, which uses a few groups of tracking stocks for their interests in the QVC Group (including commerce assets such as HSN, QVC, and Zulily), Liberty Broadband, and the Liberty Ventures Group (including internet and media assets such as Bodybuilding.com, Evite, and interests in Expedia and Time Warner).

So why use the tracking stock structure in this case? There are two reasons:

One is that there are material tax implications of selling down EMC’s VMware stake, given the low cost-basis of the shares. However, if Dell wished to part with VMware, it would have the opportunity to spin it to shareholders tax-free and reduce the overall price tag for EMC at the same time. (Some analysts have called the tracking structure “stupid” and would have preferred to see a full spinoff.)

But the second, less obvious, and more important reason for the tracking stock structure is that by keeping the underlying ownership structure intact, Dell continues to benefit from the full consolidation of VMware’s results. This helps both in the near term for utilizing cash flow to repay M&A debt, and in the long term if Dell ever chooses to come fully public again — VMware’s revenue scale, margin structure, profitability, and relative growth would appeal to investors.

What does Dell want to do with VMware?

Dell wants to be “a larger, longer-term owner” of VMware over time, according to VMware CEO Pat Gelsinger on EMC’s post-announcement call with analysts.

In the same call, EMC CEO Joe Tucci noted that EMC and Dell together will have the “opportunity to significantly expand VMware’s revenue in areas such as the software-defined data center, the hybrid cloud, and in end-user computing”. There are clear opportunities for Dell to help pull VMware into the mid-market. However, the positive revenue synergies with Dell do come with potential negative consequences to VMware’s revenue flowing from other partners, such as HP, IBM, and Lenovo.

Yet Michael Dell directly reiterated in an open letter following the deal how committed he is to VMware’s operating independence, and that he does not plan to “place any limitations on VMware’s ability to partner with any other company” or “do anything proprietary with” the company. He further stated:

“VMware is a crown jewel of the EMC federation. Our intent is only to continue to help it thrive, innovate and grow, as an independent company with an independent and open ecosystem.”

Still, how competitors react to this shifting landscape — it’s not like these strategic questions simply disappear with a statement of independence! — may be among the most interesting side effects of the Dell-EMC deal. Will this deal lead to another round of consolidation among other larger tech industry players? How will those players behave differently now, faced with the prospect of a combined Dell-EMC?

Finally, it’s worth noting that in the event Dell is forced to reduce its debt load — remember, the company will have a significant amount of debt following the deal closing — selling part of its 28% direct economic interest in VMware could be one way to generate cash. However, the tax obligation of selling down Dell’s ~81% stake in VMware would run into billions of dollars; EMC purchased its stake in VMware in 2004 for $635M and it’s now worth ~$30B. Dell is likely highly motivated to consolidate VMware’s financials.

EMC and VMware have been living with uncertainty ever since activist shareholder Elliott Management announced its stake in EMC and agitated for a sale or spinoff of VMware. So the acquisition by Dell answers the immediate question of what happens with VMware — but does not answer the longer-term question of whether VMware belongs as a quasi subsidiary within the federation, as a wholly owned subsidiary of Dell, or as a truly independent entity.

And what does VMware have to say about all this?

VMware management opened the Q&A in their recent earnings call by sharing that while there had been speculation and ambiguity about its future, “the good news is the ambiguity is now gone, because we know we’ll remain an independent company”.

While reiterating that its mission and strategy “remain unchanged”, VMware further noted that it was “very optimistic about the long-term value” for itself in the Dell-EMC merger and that it “sees opportunities for revenue synergies which could exceed $1B over the next several years” — repeating Tucci’s message in the analyst call after the deal was announced. Oh, and that they’re excited about the new Virtustream cloud unit, which they believe will become one of the top five cloud providers worldwide.

Something else of note on the Q3 earnings call — which signals the larger factors at play in the Dell-EMC deal — is the fact that VMware license bookings were below consensus estimates. While growing 7% on a constant currency basis, it was a small deceleration from the 9% growth that the company achieved in the previous two quarters.

To explain this, VMware’s COO explained (among other reasons) that “not just VMware, but the entire industry as a whole is seeing a massive secular shift right now in the market”. This bookings deceleration, which causes concern for analysts, is important to watch as it may be due to broader factors in the competitive environment — particularly the impact of containers and the public (i.e., not just “private” and “hybrid”) cloud. The platform wars, as many have argued, have now moved to the cloud … which itself is a diverse and multi-layered thing that is rapidly changing.

Rock (big company), meet hard place (activists): Why and how did EMC do this deal?

So far, this deal seems like lot of work! But legacy player EMC was hamstrung in its ability to do much else. And the reason comes down to something buried in the current narrative around the deal: the role of activist investors.

Behind the scenes of the Dell-EMC deal — years before it happened, actually — both companies had fought significant battles with activist shareholders. Dell had engaged in a lengthy and contentious battle with Carl Icahn before its take-private was completed with Silver Lake in 2013. EMC, meanwhile, had battled its own year-long activist shareholder campaign from giant hedge fund Elliott Management until a temporary standstill was reached in January 2015. That so-called truce between EMC and Elliott expired last month.

It’s worth examining Dell’s history and previous experience with activist investors, which may have played a significant role in teeing up the current deal. A key tactic in Michael Dell and Silver Lake’s fight against Carl Icahn to gain control of Dell was a change in the voting structure during the deal negotiations. This tactic changed votes from shareholders who didn’t vote — who ignored or didn’t care about the proxy packets they received in the mail — into counting as mere abstentions instead. Not voting shifted from “no” to “not counting”; in other words: the rules were changed in the middle of the game.

The results of the vote therefore favored the take-private by Dell and Silver Lake — because Michael Dell, as founder of the company, still controlled 16% of the equity, and as CEO had enough shareholder support to then win the vote. Since Icahn’s $2B stake was not enough to top Dell’s bid, Icahn was forced to drop his proposal, later reportedly complaining that Michael Dell and Silver Lake got Dell at a steal. (Icahn still walked away with an additional $500M for his stake, as Dell eventually raised his takeover offer in exchange for a change in voting rights.)

Michael Dell, meanwhile, was quoted at the time as saying that “We’re the largest company in terms of revenue to go from public to private. In another week or two we’ll be the world’s largest startup.”

And that’s the crux here: The people most personally and passionately vested in the company (Michael Dell could have just as easily walked away, yet didn’t) want the freedom to operate in a nimble, I’m-playing-the-long-game way. Activist investors, meanwhile, focus on extracting money in the short term regardless of the actual long-term business strategy — as Michael Dell put it, for activists, it’s more about the “poker game” than the company.

The Dell voting tactic is instructive in this case because it made the fight simply about who controls the vote, instead of focusing on different arguments around business direction, valuation, and fairness. Only this time, another big public company was seeking to do the same thing Dell did: Elliott-embattled EMC.

Elliott had been calling for a spinoff of VMware and a break up of EMC’s federation model as a way to unlock more value for EMC shareholders in the short term. Elliott’s thesis was simple: a fully independent VMware was worth more on its own — free from capital and competitive constraints — than it would be under EMC. Of course, this was the last thing EMC wanted for its more longer-term business goals; EMC had committed to the federation strategy as a way to “stitch together” different products to sell more integrated cloud solutions in what had become a very competitive industry environment.

Given this context, the Dell-EMC deal is a way for EMC to act on strategic growth plans while going around activists. EMC is using this deal to go private and restructure themselves outside the glare of the public market.

And the dealmakers — all veterans of previous activist fights — were shrewd: They included a 60-day “go-shop” clause — a provision that ensures better offers if any exist — in their merger agreement. Not only are they using the go-shop clause to convey that they are indeed doing their “duty to make sure we get the best deal for the shareholders” (to quote Tucci), it’s also protecting them from having to fend off shareholder lawsuits after the deal closes.

In other words: EMC and Dell are confident this is the best deal available, so let’s see who can match it or come up with anything better!

The dramatic irony, of course, is that the 45-day go-shop period in Dell’s own case is what invited activist Carl Icahn into their shareholder mix in the first place. As for Elliott, it claims to “strongly” support the current Dell transaction.

Even the timing of the deal, which has been in the works for over a year, is shrewd. There are not many industry players who could execute an acquisition of this size, and it just so happens that two of the only other potential candidates are digesting strategic transformations of their own right now: HP, which is splitting into two separate entities; and Lenovo, which is digesting two large acquisitions (IBM’s server business and Motorola Mobility).

The remaining bigger picture questions, then, are why, how, and why now are activists getting more involved in more tech deals?

Activist investors have been around for a long time, but activism has now become one of the fastest-growing asset classes in institutional investing. Assets managed by activist hedge funds rose by 269% over the last five years, and the number of activist deals rose an average of 34% a year in about the same period. Activist investors may now control almost 10% of total hedge fund capital.

Why is the activist asset class — an asset class just like any other — growing so fast? Among other reasons, the activist strategy:

…is more liquid. By getting involved with public companies most in need of operational change, activists are in some ways doing what private equity (PE) firms would do after a take-private — only they are doing it in the public markets. And while activists lose out on the full benefit of restructuring a private company (missing out on a greater reward for greater risk), an activist, unlike a PE firm, can “sell down” or dispose of the stake relatively easily. The duration of the typical holding period is much shorter as well: Activist campaigns are measured in quarters, while take-privates are measured in years.

…requires less capital. Elliott Management was able to agitate for change at EMC while owning only 2.2% of shares outstanding worth less than $1B. This is a far less capital-intensive proposition than owning, say, 100% — which in the current deal’s terms, required $4.3B even with the massive benefit of leverage. And unlike most other shareholders, who would passively buy what they consider to be undervalued companies and wait for the market to close the valuation gap, activists are more, well, active. They don’t even have to build up a majority voting rights position; they need just enough to exert their voice — and there certainly isn’t a shortage of media coverage and megaphones to amplify this “investment-drama theater” (as one of our partners dubbed it).

…has plentiful targets. A take-private requires agreement from shareholders and the board, and also often involves a premium on the current market value. Activists, on the other hand, acquire and divest stakes in public companies freely — and without management’s support. And activists aren’t only going after distressed companies; even stock-market darlings like Apple aren’t immune.

It’s not always clear whether an activist is a “reformer” (like Elliott pushing for significant structural changes at EMC) or an “agitator” (like Icahn, who Michael Dell accused of not knowing whether Dell “made nuclear reactors or french fries”). One thing is clear though — activists will continue to play a significant role in the evolving technology landscape. Especially as tech itself matures as a category.

So what now? The drama is just beginning…

The announcement of the deal was just the beginning. It could take as long as a year to receive the necessary shareholder and regulatory approvals to close the Dell-EMC deal, and there is still a risk that it doesn’t close at all. The risk is material, though we do expect the deal to pass government review given the minority combined market share.

We can expect some other upcoming drama, too.

…with EMC shareholders

The transaction still has to pass EMC shareholder approval. If EMC shareholders don’t feel they are receiving a substantial enough premium, they could vote against the deal.

However, assuming a valuation for each share of tracking stock of $81.78 (the intraday volume-weighted average price for VMware on Wednesday, October 7, 2015), EMC shareholders would receive a total combined consideration of $33.15 per EMC share. This would result in a 20% premium to Monday’s October 19 closing price of $27.72/EMC share, or even more relevant, a 35% premium to shares of EMC trading at an average of $24.64/share over the past 30 days.

The mandated 60-day “go-shop period” should also ensure that EMC shareholders receive the best deal available.

…with VMware shareholders

But what about the VMware shareholders — couldn’t they throw a fit and try to upset the deal? Don’t they get a say in all this? They certainly do.

As majority shareholder of VMWare, EMC will be casting 97% of votes due to the dual-class voting structure. That’s partly what makes the drama in this deal interesting, along with the associated price volatility in VMware shares (see appendix for an analysis of why this happened). Due to that share price drop, each EMC shareholder has theoretically seen an asset they own 81% of devalue by 41% partly as a result of the merger announcement — which could cause them to try to block this deal in its current form unless the initial market reaction proves overblown. The total value of the transaction is now $30.51 vs. $33.15 at announcement.

As for Elliott: The timing of their EMC purchase is not known because there was no requirement for an SEC filing at their ownership level. But at the last close immediately prior to disclosure, when EMC shares were $26.40 per share, this transaction is only a modest premium on their purchase price (although ahead of the S&P 500’s 1.3% decline). So Elliott will likely walk away less than satisfied, especially since they failed to break up the EMC federation and spin VMWare out. They will now move on to other targets, which is part of the activist model.

But how did VMware shareholders get into this position? The history of the EMC-VMware tie-up goes back to 2004 when EMC acquired privately-held VMware for $640 million in cash. A few years later, EMC sold 13% of VMware to the public through an initial public offering that valued the company at $19.1B. So if you are a shareholder of VMware today, you purchased your shares knowing that EMC controlled the majority of the vote and was thus in control of VMware’s destiny.

In fact, at the time of the VMware IPO, EMC detailed this very risk in the S-1 filing with the SEC. There were 14 different risk factors — not to mention 17 sub-bullets pertaining to corporate actions — attributed to EMC’s control alone; to put that number in perspective, a typical S-1 filing for an IPO details ~25 risk factors total. Every shareholder who thus knowingly bought VMWare post-EMC has no rights in any M&A transaction. Even activist investors are constrained in this way.

The creative structure of this deal is what makes it possible, and the structure wouldn’t be possible without control of VMware. It’s almost as if someone designed the whole thing up front, putting all the pieces in motion years ago. Knowing that VMware was the key chess piece, and seeing EMC’s control of it, may be what led Dell to cleverly come up with only $4.25B in equity for the deal (instead of an additional $18B in equity) through the clever tracking stock. It’s using a relic from the past to give them all a future.

…with the players and other potential bidders

In addition to the 60-day go-shop period, the transaction also includes a bilateral breakup fee arrangement whereby EMC owes Dell $2.0–2.5B and Dell owes EMC $4.0B, respectively, if the transaction is broken by either side. This arrangement creates an economic incentive for each party to follow through with the deal.

In any case, there are still only a handful of traditional IT companies that have the size to consider an acquisition of EMC — think Cisco, IBM, Microsoft, Oracle in addition to HP and Lenovo. As mentioned most of these players are too busy with their own acquisitions, and Cisco had once already stated it wasn’t interested. And another private equity buyer for EMC is unlikely due to the size of the deal and lack of cost and revenue synergies as a stand-alone acquisition.

…with regulators

There are still several regulatory milestones to pass before closing.

The first that will provide insight into the deal is the filing of the preliminary proxy statement. This is a required filing with the SEC that will include a narrative of the steps that led up to the deal, insight on negotiations, and a look inside the respective boardrooms of Dell, EMC, VMware, and associated parties.

The intent behind this filing is to give shareholders (in this case EMC shareholders) all necessary information to help them to cast an informed vote either for — or against — the transaction. Given the complexity of this transaction and the multiple parties involved, we expect this to be an interesting read. As a partner of ours noted: “This thing is going to read like a novel!”

…in the stock market

How the stock market digests the deal will primarily be expressed through how VMware stock — and to a lesser extent EMC stock — trades over the coming weeks and months. To understand how and why VMware [VMW] stock dropped sharply after the deal was announced and has fluctuated since, see the appendix.

In general, a lack of clarity tends to send stock prices in only one direction — down — and this deal and its structure were already difficult to digest. As the deal is better understood and more informed risk assessments are made, we expect the stock market reaction to be more measured and meaningful. Watchful eyes will be on each quarterly earnings call for EMC and VMware. (Unfortunately for deal watchers, Dell issued all of its take-private debt as “144a issues” and is therefore exempt from public filings.)

The proposed VMware tracking stock is a critical element of delivering value to EMC shareholders, and is therefore an important element of this transaction to, well, track!

…with the broader financial markets

The market has been anxiously awaiting Fed action on interest rates. A decision to raise interest rates could have a direct and significant impact on this deal. The current interest rate environment is very favorable to large M&A deals, and at this level of debt any movement higher in interest rates will make the deal more expensive.

Another component of the financing market to consider is the new debt issuance market and the ability of high-yield issuers — a more fickle market than investment-grade bonds — to finance such deals. Unlike highly rated and high quality companies (the likes of Google) that can finance a deal like this almost any time and in any environment, high-yield debt markets are subject to more narrow windows. Those windows crack open and shut more frequently for new issuers and are more in line with IPO windows in that sense. So if the demand for high-yield new issues dries up and new issues become sparse, that window could negatively impact closing this deal.

Finally, the IPO market — and an IPO of Secureworks — could be a component of transaction financing, easing reliance on other forms of financing.

…with competitors

VMware works closely with, and derives significant revenue from, industry partners such as Cisco, HP, IBM, Lenovo, and NetApp, among others, and several significant channel partners. So how will Lenovo, a direct competitor of Dell in PCs, work with a Dell-controlled software business? Will HP stop co-selling with VMware as a result of the deal? NetApp will now become the largest independent storage company — do they go on offense and acquire competitive, next-generation capabilities to expand their business and be a more attractive EMC alternative for the “anti-Dells”? Will Cisco finally move into storage and expand its data center offerings in a meaningful way?

It’s possible that customers won’t be affected. Connie Guglielmo reported that “Throughout the go-private saga, Dell never lost a big customer.” That may be true here, too. Still, this transaction is likely to affect the customer base in future as competitors grappling with a more formidable, combined Dell-EMC make their own ninja moves towards those customers.

…with VMware

Finally, the remaining paradox involving VMware is growth: VMware was seen by the market as the most promising growth engine for EMC, and is now viewed the same way for the combined Dell-EMC.

Yet growth investments at VMware could now be substantially curtailed, slowed, or even halted for a period. Given the required leverage pay-down, it is unlikely that VMware can invest and acquire for growth while also meeting the parent company’s mandate of debt reduction.

But if Dell curtails investment in the VMware growth and innovation engine, does it then erode a meaningful portion of the very value it’s acquiring?

And then of course there’s the broader question of virtualization as a trend — virtual machines aren’t dead, but can they keep up with the requirements of microservices, containers, and next-generation applications?

* * *

The ultimate question is — will it work? Are all these financial acrobatics going to deliver on the promise of the Dell-EMC deal as the two companies walk a high-altitude tightrope?

We’re not sure what else companies on the backside of their growth curves can do when competing with more nimble competitors, other than to consolidate, split, or restructure. We have players like IBM and Microsoft aggressively acquiring new companies to make a shift to new platforms as their core businesses decline; HP and others bifurcating themselves into more focused, slimmer, and presumably more agile players with streamlined operations so they can better address secular platform shifts; and now, we have Dell + EMC (+ VMware) consolidating their businesses to stay competitive in a rapidly changing world.

The ripple effects of all this may be far more profound than anyone currently thinks. As investors in this ecosystem, we will be watching with great interest!

APPENDIX: What’s going on with VMware stock?

If VMware is one of the “crown jewels” of this deal, why did VMware stock fall sharply after the deal was announced?

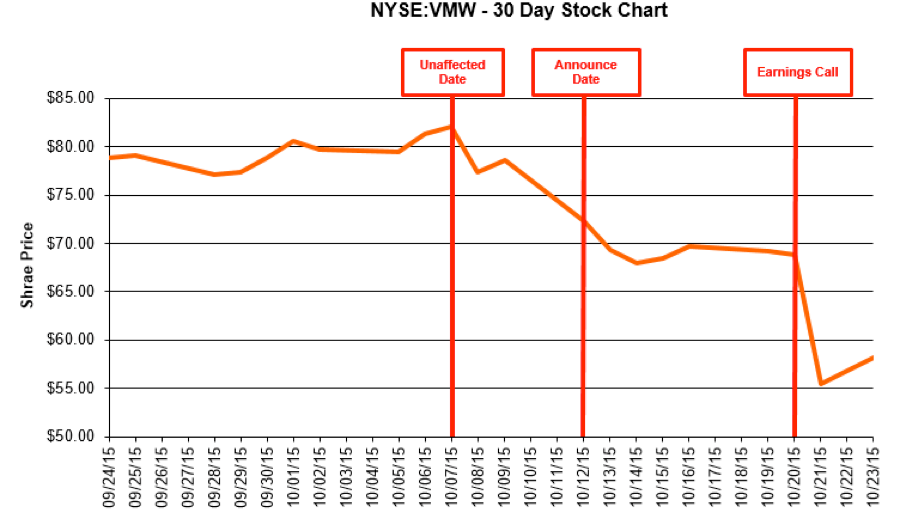

Let’s first go back to the baseline. When analyzing the impact on a company’s share price caused by an M&A transaction, investors tend to look to the “unaffected” share price, which represents the price prior to any rumors or speculation about a transaction. For VMware, the unaffected date was October 7th, when the price per share was $82.09.

As soon as investors heard about the Dell-EMC merger, however, VMware’s stock began to fall… and not just a little bit. Immediately following the announcement, the price of VMware dropped 12% to $72.27, and as of close Friday October 23nd, the stock was trading at $58.18 — down a staggering 41% from just 11 days prior:

While there’s often an initial knee-jerk reaction in such situations, there’s more happening here.

Supply of shares and the role of tracking stock

Currently, approximately 70-80 million shares — representing 19% of VMware — trade publicly.

Dell issuing approximately 223 million shares of VMware tracking stock significantly increases the public float of VMware. This is effectively a massive post-IPO lock-up expiration on the order of 53% of total shares outstanding (65% of 81%) — approximately ~$18B of value at $81.78 per share.

So the coming dramatic increase in supply of floated VMware shares probably caused some downward pressure on its stock price.

Tracking stock creates a playground for traders

Short-term stock trading is a game of speculation. After the transaction closes, speculators will not only have VMware stock, but also VMware tracking stock, as arbitrage instruments for trading the expected value of VMware.

The tracking stock may not always track the common stock tick by tick, because the tracking stock is subject to its own supply and demand, and thus will invite extra activity by short-term speculators — potentially further pressuring shares. Even prior to deal closing, merger arbitrage traders have the opportunity to short VMware and go long EMC, knowing that their EMC shares will deliver 0.111 shares of VMware tracking stock. This will provide a synthetic short cover to their VMW short, and invite additional interest in shorting VMW and therefore driving down its price in the interim.

VMware’s lackluster Q3 earnings and concern about “massive secular shifts”

VMW just reported quarterly results largely in line with estimates and expectations, but with softer billings growth than investors wanted to see. The company lowered their license revenue guidance for the year.

Furthermore, management pointed to secular headwinds impacting the business. The company is observing increased competition from private data center solutions and public cloud providers like Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services. For example, after the announcement of the transaction JMP analyst Patrick Walravens pointed to General Electric’s comments that it plans to shift 60% of its workload to AWS over the next three years.

Uncertainty over the merger and its impact on VMware

We’ve just written at length about the deal and the potential implications, some of which include uncertainty over whether or not the deal will actually get done and exactly how it will be structured. While Dell and VMware continue to contend that VMware will continue to operate as normal and not be impacted by the potential merger, investors do not always see it that way and tend to be skeptical of synergy claims.

And the the merger itself could be distracting to management as they try to focus on execution; there could be a disruption to customers that allows competitors to negatively sell against VMware.

Investors are also concerned about potential restrictions on VMware’s ability to invest in growth — especially if their cash flows are constricted (Dell made it clear that they intend to aggressively pay down their debt), and even if Joe Tucci said that “no VMware cash flows or debt capacity will be used to finance the transaction”.

Financial impact of the Virtustream business unit

EMC and VMware announcing the spinout of Virtustream as a joint venture and new business unit should have positive impact on VMware’s revenue due to its being consolidated into VMware’s financial statements.

But the new Virtustream business unit is also expected to have a negative impact on the company’s profitability or free cash flow (FCF) since cloud businesses tend to have much higher capital expenditure requirements than software businesses.

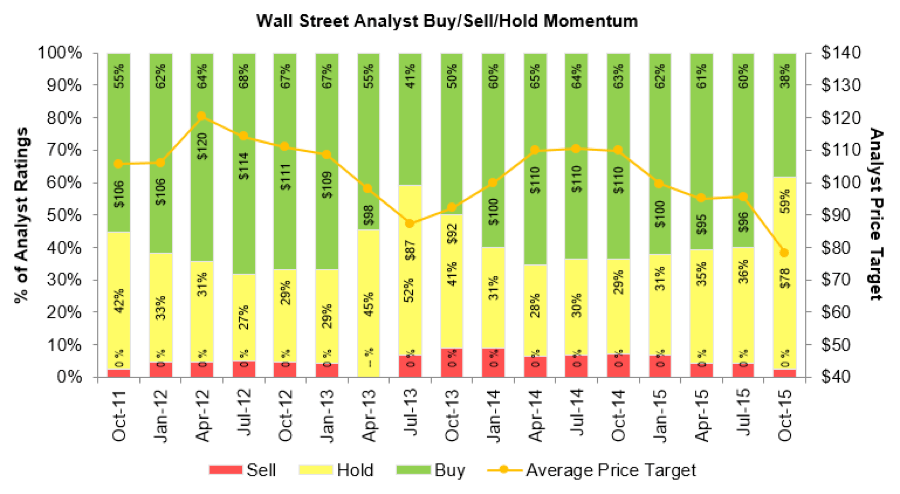

Ever-changing analyst sentiment

Preliminary commentary from Wall Street analysts wasn’t positive for VMware for all of the reasons cited above; their reactions were perhaps even more negative after the company’s earnings call.

While some of this can be considered just opinion (even if well informed) as opposed to fact, many public shareholders rely on Wall Street analysts to help them judge a company’s future prospects — most simplistically summarized as a Buy, Sell, or Hold rating. As shown in the chart below, a number of analysts have shifted their sentiments since the merger announcement about where VMW will ultimately trade based on their views about the company’s intrinsic future value:

Low float and implied volatility

Finally, the severity of the drop in VMware’s share price is somewhat exacerbated by the fact that only 17% of VMware shares are freely floating shares, i.e. available for trading.

Typically, low-float stocks have more volatility as there are a smaller number of shares to ultimately move the stock price. Which is a bit ironic given that one of the reasons for the increased trading activity is the potential for an increase in tradable stock (as a result of the merger and issuance of the tracking stock)!

Editor: Sonal Chokshi @smc90

- 16 Minutes on the News #1: Neuralink & Brain Interfaces, TikTok, FaceApp, iHeartRadio

- All about Direct Listings

- a16z Podcast: On Recent IPOs and Comparing Private vs. Public Valuations

- a16z Podcast: Dealing with Corporate Dealmakers — When to Talk to Corp Dev

- Actually, Founders Should Engage Corporate Development