As new biological technologies shift the way we make new medicines — from “bespoke craftsmanship to industrialized drug development” — we are seeing bio platforms truly deliver a dizzying array of novel discoveries, tools, and therapies, and across a variety of different business models.

Before, virtually every company in biotech claimed to have a platform… but few delivered on the promise of producing multiple new therapeutics. Now, the bio platforms of this next wave are more productive than ever before. It causes a conundrum, though: The goose can finally lay the proverbial golden eggs — thanks largely to engineering approaches — but because the platform is so broadly applicable, it becomes even more difficult to know where to start.

Especially for bio platform startups with limited resources, it’s important to select one’s first few applications wisely, in order to demonstrate that the platform can actually solve multiple problems. That’s why all founders with bio platform companies need to understand a concept that we call “platform-disease fit” (PDF, for short!). Picking the disease that a bio platform is best suited to address is among the most critical decisions that will shape a bio startup’s destiny.

Along with that comes the other critical question, of where partnerships come in: Should the startup go it alone, or seek opportunities to collaborate with strategic partners? Such partnerships come with both possibilities and peril for early-stage bio startups. On one hand, partnering with biopharma companies (large and small) enables startups to leverage the partner’s brand, capabilities, and resources while they continue to build out their own pipeline of PDF candidates. On the other hand, it takes a lot of time and effort to align at reasonable terms and with common expectations.

So in this guide we offer advice — for founders, as well as those seeking to understand and partner with bio startups — on how to shape, craft, and value a deal. In other words, maximizing the impact of a bio platform is all about the journey to finding not just platform-disease fit, but platform-partnership fit.

Shaping the deal

As with any deal, you need to understand both what the other party wants and what YOU need. For biopharma companies, it’s access to innovations outside of their four walls. Science is difficult to predict, and failures are common and costly, so these companies are constantly trying to keep their pipelines hydrated with promising drug candidates, and looking for new ways to accelerate their own discovery and development efforts.

That’s where startups come in; for many, startups = external innovation. But the innovation that startups provide can take many forms, so startups need to find a prospective biopharma partner whose needs best match what they can provide. One way to approach this is to define the “unit of value” — is it: 1) a potential clinical drug candidate; 2) a promising drug target; 3) a high-value component for an advanced therapy (i.e. AAV delivery for gene therapy),;or 4) the data to support the surfacing of 1, 2, and/or 3?

The value of the startup’s innovation to the partner is a function of the extent to which the startup’s molecule, target, etc. has been validated and de-risked. The specific value attributed here will also vary by disease area, as well as by the overall supply-and-demand equation for that particular technology at that point in time. For instance, since oncology is considered a “target-rich” environment — there are plenty of options out there — the level of validation expected before partnering is much higher than “target-poor” areas (neurodegeneration, for example).

That value is also in the eye of the beholder: Each biopharma company has specific gaps they actively want to address via partnership. A company may want to acquire more drug candidates in a particular therapeutic area, branch into a new modality, or explore the applications of a new technology. Regardless of their reasons, however, it’s obviously much easier to convince someone on something they already want to do. Positioning your platform as a viable solution to your potential partner’s priority gap will help that counterparty more easily visualize the benefits of teaming up.

But for bio platform startups, it’s not just partnership for partnership’s sake — such companies have bigger ambitions, to be impactful and enduring independent companies — which is why we must go back to the original goal of the partnership: to more quickly build out a pipeline of PDF candidates.

Startups must therefore also ask not just what they can do for the partner, but what the partner can do for them.

So what can established biopharma players do for startups? For one thing, they can help startups acquire the proof required to validate their platform — and thus validate their company’s existence. Biopharma companies can also help translate the startup’s innovation into therapies that concretely benefit patients. But be sure that what the company offers is what will most help your company accomplish its long game. Below, we’ve outlined four key sources of value that startups should rank as they approach prospective partners:

But how do startups even find the right partner? Since this is a brief guide to business development 101 for startups: Start by scanning drug pipelines, therapeutic areas, and modality priorities; and research recent scientific presentations, analyst reports, and other outputs of biopharma companies in your domain. All bio platforms have an expiration date, and the hot new thing today may not be so hot tomorrow. But keep in mind that time is also of the essence for startups; a good deal today may indeed be better than the perfect deal late next year.

Based on all of the above, prioritize your outreach list by stack-ranking against YOUR top needs from a prospective partner — remember, just as they’re buying innovation from you, you’re effectively absorbing experience from them.

Crafting the deal

After a startup has identified the best prospective partners per the above criteria, the next step is to package and position the platform as a solution to a key need of the biopharma company. We recommend doing this through a structure that can be easily understood, absorbed, and transacted on by the counterparty in the deal, and develop it through the following process: 1) find your fit, 2) find your friends, and 3) find the win-win.

Step 1: Find your fit

Biopharma companies are massive, conglomerate-like operations composed of many subunits, departments, and smaller research teams — each with their own set of targeted interest areas, business priorities, and funding. So the first challenge is to precisely identify which team within that biopharma that would put the technology to best use, AND that is willing to offer the partnership terms that the startup is seeking.

To find the right team, look up the online presences of individual team members: their recent publications on PubMed.gov, their research blogs, and even their Linkedin and Twitter profiles. These can provide clues for what the group is looking for, as teams within a biopharma company will often have a primary orientation toward a specific therapeutic area, target, or technology.

Step 2: Find your friends

The above can also provide pointers to specific individuals interested in your work; however, interest alone is not enough. Startups seeking to partner with biopharma need to find the right business or scientific leader within the company who can serve as an internal champion for your platform (this is not unlike traditional enterprise sales, in fact). While this deal may be one of the most important things to your company at the moment, it’s likely competing with several other good ideas, and priorities, within the biopharma company. Thus, having someone committed to marshaling it to the finish line is essential.

The right sponsor will have the influence, the budget, and the mandate to accelerate the startup’s deal across the finish line. So when searching for the right internal champion, consider metrics such as company tenure, previous deals completed, and their genuine excitement about the technology. (A startup’s board and investors can help with back-channel references here as well.) It also helps to have a “high-low” strategy when it comes to champions: Have buy-in at the senior-most levels (e.g., Chief Scientific Officer) — but also have a true believer on the ground at the operational levels who can manage the day-to-day tactics of the deal and help get it done. (This, again, is not unlike how enterprise sales deals happen as well.)

If you don’t yet have your own networks, leverage others’ networks. Your investors, advisors, partners, and so on can often help with a warm introduction to the right leader. Attending the big conferences (e.g. JPMorgan, BIO Partnering, ASCO, etc.) can also be helpful for expanding your network and meeting a high volume of business development (BD) professionals. We’ve even heard success stories from cold outreach messages on LinkedIn leading to real BD opportunities, likely because when there’s a precise match between needs/wants, people will pay attention.

Step 3: Find the win-win

Should a startup have a pre-baked proposal, without having heard the other side’s needs yet? Often, yes, because even if the startup is wrong in its analysis of what the biopharma company needs, it’s better than forcing the company to envision from scratch what the startup’s platform can do for them.

Again, the packaging of the opportunity (from the startup) matters; remember: The startup is the one that’s best positioned to help the biopharma company imagine how their technology can help, especially because most such deals die due to a failure of imagination.

The proposed win-win may not be exactly right up front, but at least it will provide a jumping-off point for fruitful discussions that lead to the desired alignment. Don’t try to be everything to everyone, but do run a structured process so that you are moving conversations with multiple companies at once. Not only will running a good process force you to be more disciplined on what you want as well, but you’ll likely also have more partnership choices at every step.

Valuing the deal

With so many factors that go into whether a deal ultimately reaches the finish line, the entire deal-making process appears daunting — especially since many of the factors are out of a startup’s control. Startups should focus on the factors that are within their control, including the following considerations, which we have found are critical to successfully landing a deal.

How much should I charge?

The financial payouts of any deal are typically gated by either time and/or contingency factors. Below are five components that make up most deals.

With all these variables, how do you know you’re not mispricing your deal?

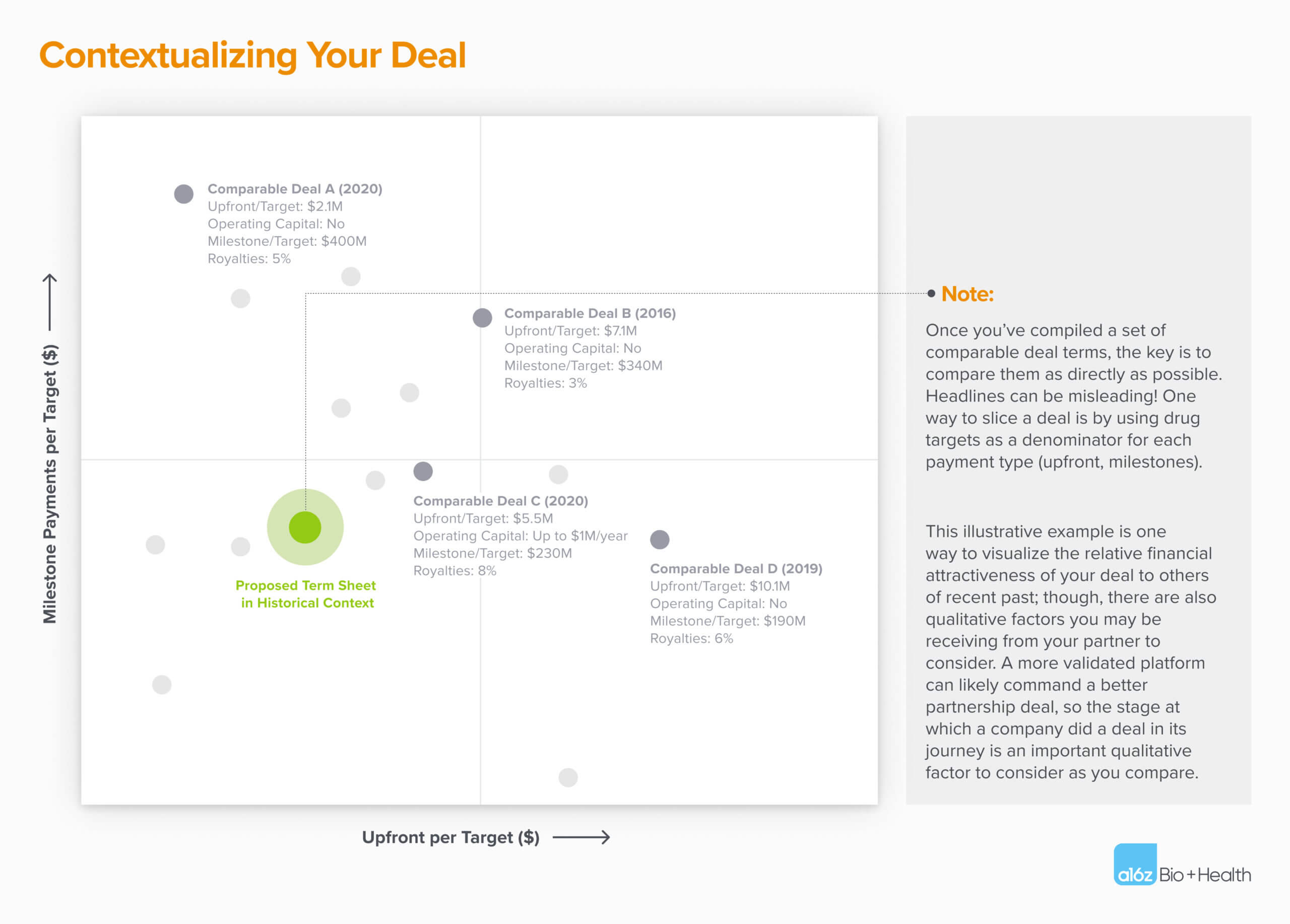

One way is to research recent deals of a similar type (technology, modality, therapeutic area, etc.) because those deals will typically set a precedent for price in your negotiations. Your counterparty will have almost certainly done this analysis; so being prepared is to your benefit! Tools such as GlobalData, BioSciDB, Cortellis, and EvaluatePharma — as well as investor analyst firm reports — will also have unredacted deal terms, or other useful deal information, often in a searchable format.

What should I include?

Scope matters. As a startup quantifies the impact of a potential partnership per above, there’s another question that should be asked: How much can they accomplish with one partner versus how much from other potential partners in the future? As a modern bio platform startup, the platform will hopefully produce a vast array of programs and applications, many of which could be partnered on in the future.

The key therefore is to create “zones of exclusivity” such that you can maximize the value and number of partnerships, while also retaining enough for yourself. As an example, if your platform is applicable across a range of indications and targets, these would be some zones to consider:

Single-target, single-indication: This zone poses the least risk of your giving away too much in one deal. The challenge here is that — with so much unknown at the earliest stages around what will eventually be commercializable — it’s difficult for the biopharma company to justify investing the time, energy, and resources to interrogate a single target, without being able to benefit from any transferability of the work across indications. (One modality breaking this trend recently is gene therapy, where the delivery vehicle and genetic cargo are developed specifically to modify a single genetic target for a specific disease; business development partnerships in this field therefore reflect that.)

Single-target, multi-indication: A more common deal type is for the biopharma to have some commercial rights across indications for the target-oriented work the startup did in partnership. This is usually a reasonable tradeoff to make, as long as the startup scopes the magnitude of the terms proportionately to the addressable market for treating those patient populations.

Multi-target, single-indication: This deal is usually the most attractive to biopharma partners looking to build a dominant franchise in a single therapeutic area. These companies typically specialize by therapeutic area or tissue/ cell type, and they will look for as many high-quality “shots on goal” as possible, diversified across targets and modalities. (Examples of this are Gilead in liver/NASH and Biogen in CNS/ neurodegeneration.) As long as you are thoughtful about your platform’s therapeutic area roadmap, this can be an effective deal type for a win-win.

Multi-target, multi-indication: This is nirvana for biopharma partners because it allows them to preserve the most optionality for the investment they make in working with a startup. The obvious problem for the startup is locking up significant portions of their company’s value. Even if the startup has scoped enough targets and indications for itself, the market (including other prospective partners and future investors) may wonder whether their platform has been cherry-picked for the areas in which they have the greatest Platform-Disease Fit. In this scenario, the startup can be perceived as having effectively sold the value of the company without selling the company — the industry sometimes refers to this as an “encumbered asset.” Avoid this situation.

All of the above zones of exclusivity apply to asset- and target-discovery-oriented deals. For deals in which the startup is transacting access to some proprietary dataset, they can view the zones as areas where they’re either providing “exclusive” or “non-exclusive” access to said data for specific use cases. Still, the same general principles apply even for these kinds of data companies; the challenge (and opportunity) is to balance the value the startup grants, and the areas they retain, in a way that is attractive to both parties… aka the win-win.

Getting to the finish line

Getting a business development deal done with biopharma can be like getting a bill through Congress — it requires a steady, but not overwhelming, cadence of communication in order to maintain momentum. Some ways the best startups manage this well:

- Being disciplined on deliverables and deadlines that are set throughout the process conveys an ability to execute effectively. A startup’s performance in the business-development process is seen as a proxy of the company’s and technology’s performance; any avoidable delays can make the counterparty lose confidence in the startup’s ability to execute on time.

- Using a “breadcrumb strategy” can keep the counterparty interested over the long journey of a deal process. Instead of waiting to show the company parts A, B, C, and D of the technology platform, validation data, and applications — all at once — the startup can trail breadcrumbs to smooth the ebbs and flows in deal momentum. Showing parts A and B, knowing full well you’ll have an opportunity to engage on C in a month, and D a few months after, can be an effective way to re-engage the company over time with new information.

- Checking in periodically with your friends at your prospective biopharma partner can reveal organizational dynamics and shifting priorities that may slow your deal. One big pharma executive told us that deals often die on the vine due to a lack of continued internal sponsorship — as opposed to any genuine disagreement on technical validity or commercial terms. Deals are done by people, not companies, after all.

Finally, be patient. The average business-development deal in biotech can take 9 to 12 months to close! But how can a startup tell whether there is still real interest in the deal or if it’s losing steam? These are three tell-tale signs that we’ve seen, as well as some advice for heading it off:

Tell-tale scenario 1: “You’re good at X, but can you do Y?”

In this situation, the counterparty is interested in the startup’s technology — but only for a specific application, which is of limited strategic interest to the startup. While it can be difficult to decipher whether there is genuine interest in partnering in area Y — or if it’s an offhand suggestion without intended commitment — exploring the new path can be a major time sink for a startup. And without the potential upside they were originally seeking from that partner!

The diversion from X to Y can also be a result of a mismatch in capabilities or interest in area X. In this scenario, it’s worth pausing to ask: Is this partner actually able to and interested in providing the sources of value that my startup needs?

Tell-tale scenario 2: The science team loves it, but the business team doesn’t

In this situation, the research scientists and principal investigators (PIs) are compelled by the startup and its technology, but the business development leads don’t have the same level of conviction. This results in either decreasing deal momentum and/or a deal offer with far less attractive commercial terms for the startup.

Since the BD lead on their end is trying to calculate the financial return on their investment of time, energy, and resources by partnering with the startup — all while earning buy-in from multiple internal stakeholders — the startup can make the BD lead’s job easier by doing the calculation for them. Include a detailed financial projection and project plan in the proposal outlining the resources required and benefits of the partnership. No matter how compelling the deal is, the deal champion will hit roadblocks internally; make sure to arm them with the tools they need to shepherd the deal and run through the internal walls for the startup.

Tell-tale scenario 3: The business team loves it, but the science team doesn’t

This situation is the inverse of the above, where there’s lackluster interest from the science teams, despite a clear portfolio fit with the biopharma’s company strategy and interest from the business development side.

The question here is whether the lack of interest is due to a genuine misalignment in strategy, or something else? If it’s something else, a common failure mode is that there’s an internal team attempting a similar approach to the startup, so the potential partnership is competing directly with an internal effort — also known as “Not Invented Here” (NIH) syndrome.

Since the insiders have an obvious home-court advantage, it’s time-consuming to resolve these sorts of delays. One way to mitigate this and align objectives is to identify the business leader of the organization where the internal effort is happening, and then frame the partnership as an additional, complementary experiment that can collectively help them achieve the business objectives for their group (i.e. getting a promising candidate into the clinic, etc.).

On a related note: Company culture will affect the deal execution as well. Signing one’s first partnership with a biopharma partner is an exciting milestone for a startup, but it’s only the beginning. While such partnerships are memorialized on paper, they are borne out through the very human interactions between the organizations. The most successful partnerships are those that bring two different cultures together. So before signing the agreement, clearly define the individuals from each organization who are responsible for each activity, handoff, decision, and milestone approval. Making this a part of the negotiation can be revealing, too: If the two parties have trouble aligning on a reasonable operating model before signing, it probably won’t be a happy marriage!

* * *

This guide is meant as a starting point for bio founders looking to explore their increasingly productive platforms in collaboration with larger biopharma companies, but there are many other questions remaining: Who should you hire as a business development leader within your own company, and when? How do you keep partnerships on track, and avoid scope creep? How do you navigate the tensions and challenges that inevitably arise when a startup collaborates with a larger company?

There’s a lot more nuance to consider when crafting and executing your business development strategy. But if you take one thing away from this guide, remember: Platform-partnership fit is a means to an end, not the end in itself. Business development partnerships are just one tool to accomplish the ultimate mission, which is to harness the full potential of your technology platform to build an enduring company that impacts many lives for years to come.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to our friends at Camp4 Therapeutics and Scribe Therapeutics (both a16z portfolio companies), as well as Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, and others for their contributions in reviewing, shaping, or pushing our thoughts here.