This post is all about network effects and critical mass. But it’s also about applying those concepts as important mental models in business, so I will share a short story about a business decision I once made that required me to consider network effects.

The Internet bubble had popped by 2002, and a lot of people were looking for the next big thing. One day that summer, my friend told me about the idea behind Friendster, which sounded promising: “system, method, and apparatus for connecting users in an online computer system” (according to patent number 7,069,308).

The Internet bubble had popped by 2002, and a lot of people were looking for the next big thing. One day that summer, my friend told me about the idea behind Friendster, which sounded promising: “system, method, and apparatus for connecting users in an online computer system” (according to patent number 7,069,308).

Friendster was pioneering what would become known as a social network.

By the time I was evaluating this potential investment in 2002, I had become a disciple of Charlie Munger’s “lattice of mental models” approach to making decisions. One of the best descriptions of mental models I’ve seen is Nobel-prize winning social scientist Herbert Simon’s original framing of the concept, where he states that better decision makers have at their disposal repertoires of possible actions; checklists of things to think about before acting; and “mechanisms in mind to evoke these, and bring these to conscious attention when the situations for decision arise.”

So a mental model isn’t a passive framework, it’s something to actively use in making decisions. In each case you must decide not only which mental models to apply, but which ones are most important. Each model is like a different filter or tool. The mental models are applied in parallel and not in a serial, step-by-step way. The process is necessarily analog in nature since in most cases assumptions are rough, the systems involved are complex adaptive systems, and different models can be self-reinforcing. The process is also based on experience: The decision maker is usually applying judgment most often acquired from when he or she made mistakes in the past.

a mental model isn’t a passive framework, it’s something to actively use in making decisions

One of the most important mental models in business is the concept of network effects. This is especially true today, when other factors that can create a moat against competitors — brand, regulation, supply-side economies of scale, and intellectual property (like patents) — are under threat. As software continues to “eat the world,” network effects become even more important as a factor in creating a moat since that’s the primary way software companies build a barrier to entry against competitors. That’s why venture capital firms investing in software-based startups include network effects in the business attributes they are looking for

Nothing scales as well as a software business, and nothing creates a moat for that business more effectively than network effects.

Network effects don’t always lead to direct financial or long-term value, however. For example, a standard like Ethernet generates network effects and benefits that last longer than one would expect for supply-side economies of scale. But Ethernet also illustrates that sometimes no one directly financially benefits from the standard itself (since it is owned by no one). And even if network effects are strong initially, as with DEC, Palm, and BlackBerry — they can be brittle and disappear relatively quickly, as those businesses discovered.

Nothing scales as well as a software business, and nothing creates a moat for that business more effectively than network effects

Network effects as a mental model

Network effects exist when the “value” of a format or system depends on the number of users. These effects can be positive (for example, a telephone network) or negative (for example, congestion). They can also be direct (increases in usage lead to direct increases in value to users, as with the telephone) or indirect (usage increases the production of complementary goods, as with cases for mobile phones). Network effects can protect valuable markets, or not much of a market at all in terms of financial value.

Network effects can exist in settings that are not obvious. Take ESPN for example. It has demand-side economies of scale (aka network effects) — most notably for SportsCenter — since the more people who watch the ESPN channels, the more valuable the channels are to each user because those particular images will be the basis of discussion for sports fanatics. Partly due to those network effects, ESPN has a competitive advantage compared to Fox and other sports channels that have a hard time replicating the demand-side effects. When someone says “did you see X do Y in the Z game?” if you watched the Fox version of SportsCenter, you may not have seen the particular video clip.

In tech, significant market adoption of a proprietary format or system can create a network effect and a competitive advantage for a business that is similar to supply-side economies of scale. But network effects are potentially more powerful. Unlike supply-side economies of scale, the benefits of demand-side economies of scale can increase in a nonlinear manner, especially in software businesses. This means that the benefits realized by a Google are far larger than those realized by a large steel or cement producer based on supply-side economies of scale. Google has at least two beneficial demand-side economies of scale — one for search and one for advertising targeting — that are mutually reinforcing and accordingly give it a strong moat. As Munger has observed: “I’ve probably never seen such a wide moat” and “I don’t know how you displace Google.” Om Malik writes about this winner-take-all dynamic as well.

For the owner of the platform, such as Google in this case, the networks effects form the basis of a powerful moat that bestows sustainable competitive advantage. A company may have revenue without some form of a moat, but it is highly unlikely it will be sustainably profitable over time without one.

Some network effects are strong and some are weak. For example, Google’s moat in the advertising-serving business is strong. Yahoo’s moat in the financial news market (Yahoo Finance) is very weak. Some markets impacted by multi-sided makers with network effects are big and lucrative (e.g., ESPN or Bloomberg’s terminal business) and some are not (Yahoo Sports).

Some companies have both demand and supply-side economies of scale. Amazon has both, and they reinforce each other. For example, the more people who provide comments on Amazon the more valuable it becomes to other users due to demand-side economies (everybody knows to find reviews on Amazon). Amazon also has huge advantages on warehouses and the supply chain on the supply-side, which it passes along to its customers in the form of lower costs.

In fact, most companies have both supply-side and demand-side economies of scale. However, these fall along a continuum of weak to strong. The Holy Grail for an entrepreneur is demand-side economies of scale that can cause a market to “tip”, giving almost the entire market to one company (winner-takes-all). Markets are more likely to tip if scale economies are high and the consumers have a low demand for variety. At one point, demand for online auctions tipped strongly to eBay. Over time that tipping phenomenon has weakened.

But the reality is that most demand-side economies do not cause a market to “tip” and yield a single winner. For example, the rental car industry has a number of providers since weak demand-side economies in that business were not strong enough to make the market tip.

When applying network effects goes too far

When I was applying the mental model of network effects to the Friendster decision back in 2002, I saw potential for a big financial upside. My experience in the wireless industry led me to conclude that the more people who used Friendster, the more valuable it would become.

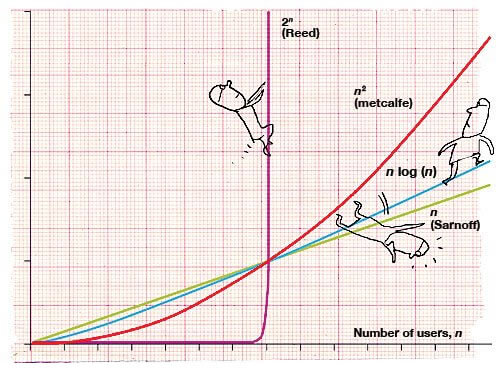

But I had just come through the Internet bubble and seen how people had taken the concept of network effects too far — and without sufficient depth — led by “Piped Pipers” of financial doom like George Gilder, who first formulated Metcalfe’s Law. An article by Briscoe, Odlyzko, and Tilly describes the folly:

“By seeming to assure that the value of a network would increase quadratically — proportionately to the square of the number of its participants — while costs would, at most, grow linearly, Metcalfe’s Law gave an air of credibility to the mad rush for growth and the neglect of profitability. It may seem a mundane observation today, but it was hot stuff during the Internet bubble.”

The article goes on to propose that more realistically:

“the value of a network of size n grows in proportion to n log(n). Note that these laws are growth laws, which means they cannot predict the value of a network from its size alone. But if we already know its valuation at one particular size, we can estimate its value at any future size, all other factors being equal…. The fundamental flaw underlying… Metcalfe’s law is in the assignment of equal value to all connections or all groups.”

The point is that the strength of network effects is not just determined by the number of participants in a network. Affinity between participants, and the value of trade between those participants, matters. As the authors of the article referenced above observe, the increasing value “lies somewhere between linear and exponential growth” — and where exactly it fits will vary from case to case, as amusingly shown by this illustration from Serge Block [via Thoughts Illustrated]:

(As an aside, I had found Andrew Odlyzko’s ideas to be particularly useful in the past, most notably when he wrote important papers debunking claims about the rate of Internet growth. For example, it was while reading Odlyzko’s paper in November of 2000 that I realized: “Holy crap, Cisco’s Internet growth numbers are rubbish.”)

the strength of network effects is not just determined by the number of participants in a network

Ultimately, I decided not to invest in Friendster due to potential conflicts in some other work I was doing at the time. But my instincts about it benefitting from network effects turned out to be correct: By June 2003 the service had 835,000 registered members; four months later, there were more than two million.

Yet growth would eventually stall. And Friendster would be overtaken first by MySpace and then conclusively by Facebook. Why?

Critical mass as a related mental model

There are a number of autopsies written about what went wrong with Friendster. The only thing they really share in common is that they are all guesses about the outcome of complex adaptive systems. So opinions on “what happened to Friendster” are like belly buttons — everyone has one, and they are all different. Wired magazine summarizes the conclusion of one opinion, citing David Garcia, a professor with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology:

“What they found was that by 2009, Friendster still had tens of millions of users, but the bonds linking the network weren’t particularly strong. Many of the users weren’t connected to a lot of other members, and the people they had befriended came with just a handful of their own connections. So they ended up being so loosely affiliated with the network, that the burden of dealing with a new user interface just wasn’t worth it. ‘First the users in the outer cores start to leave, lowering the benefits of inner cores, cascading through the network towards the core users, and thus unraveling,’ Garcia told us.”

Garcia raises an important issue related to network effects here, though: that of critical mass, which is yet another mental model.

The term “critical mass” came into use around 1941 though it originally had a very limited definition: the minimum amount of a given fissionable material necessary to sustain a nuclear chain reaction at a constant rate. While not the first to use the term in a physics setting, the physicist Leo Szilard is said to be the first person to propose that a chain reaction could be created starting from a critical mass of uranium. And that’s the critical point behind the concept as we apply it today.

Soon, other disciplines began to use the term “critical mass” as a mental model. One of the first people to apply it to the social sciences was the same person who created the mental models construct — Herbert Simon. His influential essay on critical mass, “Bandwagon and underdog effects and the possibility of election predictions”, was published in 1954. (Simon later went on to win the Nobel Prize “for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations”.)

Other definitions of critical mass exist for other disciplines. In business, critical mass refers to “the size a company needs to reach in order to efficiently and competitively participate in the market. This is also the size a company must attain in order to sustain growth and efficiency.” In a technology business, critical mass refers to the level of users that are required to help create a set of network effects that are so strong, that they build a moat for that particular business. Sometimes there is no second place in a market when network effects are that strong.

Critical mass is present in a platform business if a sufficient number of users adopt an innovation in a system so that adoption of those innovations becomes self-reinforcing. The classic example people cite to illustrate this point was the competition between the Beta and VHS videocassette formats in the 1970s. Beta was considered to be the superior format in terms of quality but VHS reached critical mass first. A research paper by Sangin Park notes:

“The tipping and de facto standardization of the VHS format in 1981-1988 is believed to have been caused by network externalities [aka network effects]. In the time period, watching prerecorded videotapes such as movie titles became the most important reason to use VCRs. Hence an increase in the users of VHS VCRs could raise a variety of available movie titles and thus the demands for VHS VCRs. That is, indirect network externalities became signification in the home VCR market.”

Getting to critical mass when creating a multi-sided market is sometimes called overcoming the “chicken and egg problem”, which can be stated simply as: How do you get one side to be interested in a platform until that other side exists (and vice versa)? How did someone sell the first ever fax machine when there was no one on the other end to receive the fax yet? (Obviously that salesperson had to sell at least two machines.)

But in the case of complements that are different — such as game developers making games for Sony consoles before there were even a lot of consoles out there — how do you get one side (developers or console buyers) on board in the first place? In Sony’s case, it sold game consoles at a loss to build up a base of users that would attract developers. As with all network effects, this eventually resulted in a flywheel effect where enough developers made enough games to attract enough users (players) which in turn attracted more developers and thus resulted in more games for more those players and a stronger user base for developers and so on.

How do you get one side to be interested in a platform until that other side exists?

What happens if a market does “tip”… but it’s the competitor that reaps those benefits? Well, that’s what happened to MySpace with Facebook. MySpace started to monetize before the social networking market “tipped”. Facebook held off monetizing until its moat was secure. Zuckerberg was patient about waiting for the market to tip whereas Rupert Murdoch was not. So MySpace paid the price and Facebook reaped the rewards.

Some mental models should be weighted more than others

The mental models approach is simpler than it seems. There are about 100 important mental models (which come from multiple disciplines) that a person should use. “Fortunately,” as Munger says, “it isn’t that tough because 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.”

I’d argue that network effects and critical mass are two of these mental models that carry a lot of weight.

You do not need to know every mental model or even know them all deeply to make better decisions, but you do need to understand how most of them work at a basic level at least. Speaking about that importance of balancing depth vs. breadth, Charlie Munger recently said “The trouble is you make terrible mistakes everywhere else without [extreme specialization], so synthesis should be a second attack on the world after specialization. It is defensive, and it helps one to not be blindsided by the rest of world.”

In business, specialization helps acquire comparative advantage. But not being wise can bite you in the rear end.

The application of a mental model from physics to other disciplines – as well as business or life questions — is intended to be a method of improving general thought. But it’s pure folly to assume that formulas from physics can be applied in human affairs and produce the same predictive outcomes. As Richard Feynman says, electrons do not have feelings like people. The real world — which is a nest of complex systems — can’t be modeled like a physical system. The trick is to apply the basic ethos of physics in your metal model without assuming that the real world can be modeled with formulas containing Greek letters.

Ultimately, the goal is to use mental models — like network effects and critical mass — to increase the probability of correct decisions. It is far better to be roughly right rather than to be precisely wrong in doing so.

12 x 2 quotes on network effects and critical mass

Network effects

1. “When the value of a product to one user depends on how many other users there are, economists say that this product exhibits network externalities, or network effects.” Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian

2. “A network effect exists when the value of a good increases because the number of people using the good increases. All things being equal, it’s better to be connected to a bigger network than to a smaller one. Adding new customers typically makes the network more valuable for all participants because it increases the probability that everyone will find something that meets their needs. So getting big fast matters, not only because it creates more value, but also because it assures that competing networks never take hold.” Michael Mauboussin

3. “Network effects are tricky and hard to describe but fundamentally turn on the following question: Can the marketplace provide a better experience to customer “n+1000” than it did to customer “n” directly as a function of adding 1000 more participants to the market? You can pose this question to either side of the network – demand or supply. If you have something like this in place it is magic, as you will get stronger over time not weaker.” Bill Gurley

4. “Businesses [can] create barriers to entry through “network effects”, in which the value of a service to a user increases as others use it. This can potentially arise in a number of ways: for example a proprietary data asset; the marketplace dynamics of having a robust set of sellers and buyers; or through the development of a community that openly shares and exchanges information. In an era where the initial cost to develop the prototype of a product has been dramatically reduced, where there are mature and scalable open source tools and services to utilize for that development, and where cloud infrastructure is available on demand and at a variable cost, defensibility may no longer be found in the technology underpinnings — the code or IP — of a service. Defensibility may however arise through the growth of service that gets more valuable, and more interesting, with each new participant.” Union Square Ventures

5. “A popular strategy for bootstrapping networks is what I like to call ‘come for the tool, stay for the network.’ The idea is to initially attract users with a single-player tool and then, over time, get them to participate in a network. The tool helps get to initial critical mass. The network creates the long term value for users, and defensibility for the company.” Chris Dixon

6. “Network effects can be powerful, but you’ll never reap them unless your product is valuable to its very first users when the network is necessarily small….Paradoxically, then, network effects businesses must start with especially small markets. Facebook started with just Harvard students–Mark Zuckerberg’s first product was designed to get all his classmates signed up, not to attract all people of Earth. This is why successful network businesses rarely get started by MBA-types: the initial markets are so small that they often don’t even appear to be business opportunities at all.” Peter Thiel

7. “…there are what I call groove-in effects tied to customers and consumers. Basically, this means that the more I use a product, the more I’m familiar with that product, the more convenient it gets for me. I use Microsoft Word. There might be a better program out there, but I know all the tricks with Word that I mastered over several years and I am very reluctant to give that up to start over with another product.” Brian Arthur

8. “The answer [to creating a flywheel] lies in two essential variables: the size of the market and the strength of the value proposition. Any growth goes through an exponential curve, then flatters with saturation. If the ceiling of the market opportunity is $200 million, even if you get a flywheel, it will take you from twenty to sixty or seventy, then peter out because you saturated the available space. The bigger the market the more runway you have — so if you hit that knee of the curve, you can grow exponentially and keep going for a long time. Doubling a business of material size for three to four years leads to a really large, important company. That’s a key element in the flywheel idea.” Roelof Botha

9. “In marketplace businesses, sell-through rate can also go by “close rate”, “conversion rate”, and “success rate”. Regardless of what it’s called, sell-through rate is one of the single most important metrics in a marketplace business. As investors, we like to see a relatively high rate so that suppliers are seeing good returns on the effort they put into posting listings on the marketplace. We also like to see this ratio improving over time, particularly in the early stages of marketplace development (as it often indicates developing network effects).” Andreessen Horowitz, 16 Metrics

10. “Because the long-run success of a song depends so sensitively on the decisions of a few early-arriving individuals, whose choices are subsequently amplified and eventually locked in by the cumulative-advantage process, and because the particular individuals who play this important role are chosen randomly and may make different decisions from one moment to the next, the resulting unpredictably is inherent to the nature of the market. It cannot be eliminated either by accumulating more information — about people or songs — or by developing fancier prediction algorithms, any more than you can repeatedly roll sixes no matter how carefully you try to throw the die.” Duncan Watts

11. “Ultimately, we’re all social beings, and without one another to rely on, life would be not only intolerable but meaningless. Yet our mutual dependence has unexpected consequences, one of which is that if people do not make decisions independently — if even in part they like things because other people like them — then predicting hits is not only difficult but actually impossible, no matter how much you know about individual tastes. The reason is that when people tend to like what other people like, differences in popularity are subject to what is called “cumulative advantage,” or the “rich get richer” effect. This means that if one object happens to be slightly more popular than another at just the right point, it will tend to become more popular still. As a result, even tiny, random fluctuations can blow up, generating potentially enormous long-run differences among even indistinguishable competitors — a phenomenon that is similar in some ways to the famous “butterfly effect” from chaos theory.” Duncan Watts

12. “Network effects can be classified along a spectrum, with stronger and weaker forms.” Michael Mauboussin

Critical mass

1. “The notion of a critical mass — that comes out of physics — is a very powerful model.” “Adding success factors so that a bigger combination drives success, often in non-linear fashion, as one is reminded by the concept of breakpoint and the concept of critical mass in physics. Often results are not linear. You get a little bit more mass, and you get a lollapalooza result. And of course I’ve been searching for lollapalooza results all my life, so I’m very interested in models that explain their occurrence. An extreme of good performance over many factors.” Charlie Munger

2. “We don’t have automatic competitive advantages. We’re seeing some more insurance volume, mainly from General Re, and Cort and Precision Steel have momentum, but we have to find future advantages through our own intellect. We don’t have enough critical mass and momentum in place at Wesco, so investors are betting on management.” Charlie Munger. He is saying that he does not like a situation where he does not have critical mass in the business or businesses he controls and that sometimes we must rely on having better management. He would prefer to have business that even an idiot can run successfully but sometimes that is not the case.

3. “There will be certain points of time when everything collides together and reaches critical mass around a new concept or a new thing that ends up being hugely relevant to a high percentage of people or businesses. But it’s really really hard to predict those. I don’t believe anyone can.” Marc Andreessen

4. “One clear lesson in the history of technology and business is that once an open standard gains critical mass, it is extremely hard to derail. The x86 computing architecture and the Ethernet networking standard are two salient examples of this truism. Once a single inter-operable standard gains the acceptance of multiple vendors in a marketplace, a consumer bias toward compatibility and scale economics create an increasing returns phenomenon that is nearly unassailable.” Bill Gurley

5. “Economies of scope and agglomeration are obtained by the presence of a critical mass of consumers…. Using a chemistry analogy, we hypothesize that (see Stuart Kaufman and Brian Arthur), a critical mass of consumers and producers, a ‘soup’ with sufficient diversity of consumers, producers, ideas, skills, at a sufficient scale and critical mass will become autocatalytic. Economic activity, newly catalyzed business activity, and other surprise will emerge. Emergent behavior, surprising and unplanned, is a well-known behavior of complex systems and a manifestation of the invisible hand of Adam Smith.” Vinod Khosla

6. A tipping point is “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point.” Malcolm Gladwell

7. “Phase transitions are unusual points in the ‘phase space’ of possible states, while most of this space is occupied by stable states.” “There seem to be ‘laws’ [of] social systems that have at least something of the character of natural physical laws, in that they do not yield easily to planned and arbitrary interventions. Over the past several decades, social, economic and political scientists have begun a dialogue with physical and biological scientists to try to discover whether there is truly a ‘physics of society’, and if so, what its laws and principles are. In particular, they have begun to regard complex modes of human activity as collections of many interacting ‘agents’ — somewhat analogous to a fluid of interacting atoms or molecules, but within which there is scope for decision-making, learning and adaptation.” Philip Ball

8. “At a certain scale, a system reaches a critical mass or a limit where the behavior of the system may change dramatically. It may work better, worse, cease to work or change properties. Small interactions over time slowly accumulate into a critical state — where the degree of instability increases. A small event may then trigger a dramatic change like an earthquake. A small change may have no effect on a system until a critical threshold is reached. For example, a drug may be ineffective up until a certain threshold and then become effective, or it may become more and more effective, but then become harmful. Another example is from chemistry. When a system of chemicals reaches a certain level of interaction, the system undergoes a dramatic change. A small change in a factor may have an unnoticeable effect but a further change may cause a system to reach a critical threshold making the system work better or worse. A system may also reach a threshold when its properties suddenly change from one type of order to another. For example, when a ferromagnet is heated to a critical temperature it loses its magnetization. As it is cooled back below that temperature, magnetism returns.” Peter Bevelin

9. “Silicon Valley has evolved a critical mass of engineers and venture capitalists and all the support structure — the law firms, the real estate, all that — that are all actually geared toward being accepting of startups.” Elon Musk

10. “Startups with a customer base need to maintain an ongoing dialog with their customers — not make a set of announcements when the founder thinks it’s time for something new. This is why entrepreneurship is an art. When you have a critical mass of customers, there’s a fine line between sticking with the status quo too long and changing too abruptly.” Steve Blank

11. “If you tell Facebook about your startup before you reach critical mass, you are an idiot.” Jason Calacanis

12. “Critical Mass.” Dr. Evil

This post was syndicated by permission of the author. About the author: Tren Griffin’s professional background has primarily involved areas where business meets technologies like software and mobile communications. He currently works at Microsoft. Previously, he was a partner at private equity firm Eagle River (established by Craig McCaw) and before that, a consultant in Asia. Griffin’s latest book, Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor is about the legendary Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman, and how he invokes a set of interdisciplinary “mental models” involving economics, business, psychology, ethics, and management to keep emotions out of his investments and avoid the common pitfalls of bad judgment.

notes and sources

Describing People as Particles Isn’t Always a Bad Idea http://nautil.us/issue/33/attraction/describing-people-as-particles-isnt-always-a-bad-idea

Metcalfe’s Law is Wrong

http://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/networks/metcalfes-law-is-wrong

A Lesson on Elementary, Worldly Wisdom As It Relates To Investment Management & Business https://old.ycombinator.com/munger.html

Is Justin Timberlake a Product of Cumulative Advantage? http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/magazine/15wwlnidealab.t.html

Sangin Park: Strategic Maneuvering and Standardization: Critical Advantage or Critical Mass? http://repec.org/esFEAM04/up.4969.1080375989.pdf

All Markets Are Not Created Equal: 10 Factors To Consider When Evaluating Digital Marketplaces

http://abovethecrowd.com/2012/11/13/all-markets-are-not-created-equal-10-factors-to-consider-when-evaluating-digital-marketplaces/

Investment Thesis at USW

https://www.usv.com/blog/investment-thesis-usv

Essays on Network Effects

http://yaya.it.cycu.edu.tw/online/Thesis-revised.pdf

16 More Startup Metrics

https://a16z.com/16-more-startup-metrics/

Dynamic Oligopoly with Network Effects http://www.stern.nyu.edu/networks/Dynamic_Duopoly_with_Network_Effects.pdf

An Interview with W. Brian Arthur

http://www.strategy-business.com/article/16402?gko=8af4f

A Conversation with Three Scientists

http://www.katarxis3.com/Three_Scientists.htm

Philip Ball Critical Mass

http://www.amazon.com/Critical-Mass-Thing-Leads-Another/dp/0374281254

The Innovator’s Ecosystem

http://www.khoslaventures.com/wp-content/uploads/RISCNov.2003.pdf

The Rise of Open-Standard Radio: Why 802.11 is Under-Hyped http://abovethecrowd.com/2004/02/02/the-rise-of-open-standard-radio-why-80211-is-under-hyped

A Dozen Things I’ve Learned from @pmarca

http://25iq.com/2014/06/14/a-dozen-things-ive-learned-from-marc-andreessen/

Notes for a history of the critical mass model

http://yaya.it.cycu.edu.tw/online/Thesis-revised.pdf

Critical Mass

http://www.comnetwork.org/2009/01/critical-mass/

Critical Mass Investopedia

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/critical-mass.asp#ixzz3yr6eE7DR

Critical Mass Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_mass_%28sociodynamics%29

What Ever Happened to Critical Mass Theory http://www.uvm.edu/~pdodds/files/papers/others/2001/oliver2001.pdf

Latticework of Mental Models: Critical Mass

http://www.safalniveshak.com/latticework-mental-models-critical-mass/

-

Tren Griffin