There’s a new era of AI consumer-based apps spreading around the world, though starting from China.

TikTok, a short-form mobile video app, was downloaded on Apple’s App store more than 104 million times during the first half of 2018 — making it the world’s most downloaded app in that period. In fact, installs in the United States in the month of October [or more specifically, between 09/29/18-10/30/18] were higher than Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube, reaching a whopping 42.4% of downloads among those already popular apps. Yet much of the coverage on TikTok either compares it to Facebook’s direct competitor (Lasso), or incorrectly labels it as a lip sync app for teenagers. It’s more.

Not only is TikTok a China-based company whose product is winning hearts in the U.S. and around the world, it is, more importantly the first mainstream consumer app where artificial intelligence IS the product (I argue why below). It’s representative of a broader shift, where AI is transitioning from the discovery phase to the implementation phase.

So what happens when AI research comes to life in a mass-market consumer app? In this post, we’ll examine three examples of consumer apps, originally from China (though TikTok is already used beyond China) that are really drawing on AI to reshape product, provide trust in anonymity (yes!), and unlock massive cost savings and accessibility. AI is not a feature, but the product… and this phenomenon will spread around the world.

AI consumer app example #1: TikTok, and why it matters

Often misclassified as a lip sync platform based off its predecessor Musical.ly, TikTok is a mobile app that displays full screen short videos — a max of 60 seconds — and uses AI to personalize the user’s video feed. Clips play continuously, and users can swipe up if they want to skip ahead; there’s also commenting, liking, and the early seeds of a stranger-to-stranger social network. Recently, TikTok partnered with the NBA to show behind-the-scenes footage and highlights, as well as showcase celebrities (including Jimmy Fallon and Cardi B) to create fun “challenges” for community engagement.

It’s like TV, but without a remote control — thanks to AI

TikTok is fully reliant on AI, and that makes all the difference. Rather than asking users to tap into a video thumbnail or click into a channel, the app’s AI algorithms decide which videos to show users. The full-screen design of TikTok allows every video to unveil both positive and negative signals from users (positive = a like, follow, or watching until the end; negative = swipe away, press down). Even the speed at which users swipe a video away is a relevant signal.

Instagram, on the other hand, uses AI as a tool instead of the actual product. Although AI helps determine the recommended videos shown in one’s Instagram’s explore feed, the thumbnail presentation gives the platform less clear signaling of likes and dislikes. If someone didn’t click into a thumbnail, is it really because they wouldn’t like that video?

How is this different than platforms and products like Facebook news feed, Netflix, Spotify, and YouTube, which all also famously use recommendation algorithms to users on what to pay attention to (whether news, shows, music, or videos)? I’d argue that the approach that the apps mentioned in this post take a more AI-centric approach, each in different ways. TikTok, for example, never presents a list of recommendations to the user (like Netflix and YouTube do), and never asks the user to explicitly express intent — the platform infers and decides entirely what the user should watch.

This may be a matter of degree not just kind, but I’d also argue that even seemingly small differences shouldn’t be underestimated: Who thought disappearing stories would change so much of social networking as we know it? By taking such a fully AI-reliant approach, TikTok users are more likely to see short videos of topics they would never explicitly search or express interest in on YouTube (e.g., of manufacturing lines), opening up new routes to serendipitous discovery.

A broad talent and content pool

The diversity of content in TikTok is as wide as YouTube, with TikTok users competing to push the boundaries of what’s possible with short clips. Music and lip syncing is a portion of the content, but so is artwork, cookie-decorating, hair tutorials, DIY science experiments, jokes, and video memes that allow users to add their own twist to preexisting songs and videos. This format lowers the barrier to entry for content creation, facilitates a sense of shared community among users, and does not require a large song selection. Some musicians have also enjoyed broader promotion and distribution from TikTok memes: In the case of Deep Chills, the creator of the music clip behind #shoechange, his song has been used to create over 5.5 million videos.

15 seconds of fame

Since most TikTok videos are 15 seconds today, creators don’t need to speak, and some don’t even show their face. This allows a whole new crop of creators that would not succeed on YouTube and Instagram to find their internet followings, expressing themselves in new ways. Additionally, the lack of “voice” means a fair amount of platform content has global appeal without requiring translation. The short length also requires videos to be entertaining at the get-go, providing instant gratification and habit-forming predictability for users, as well as the incentive to keep trying new genres of content.

The Happy Place

Because TikTok completely controls what users see, and uses AI to do so, it can optimize the video feed for user happiness. The platform can decide to show videos that are upbeat, funny, and/or wholesome — in fact, the entire vibe of the platform is largely under TikTok’s control because they, not users, decide which videos to display. Even if a user subscribes to a creator, there is no guarantee that he/she will see all of the creator’s videos. This product design ups the ante for the platform’s algorithms because a series of misses will cause users to close the app. Unlike other social networks where communication is part of the core value proposition, if a user stops using the U.S. version of TikTok, it is harder for TikTok to win him/her back.

A Trojan horse to social networking?

Just as the U.S. version of WeChat only showcases a subset of the app’s functionality, TikTok only has a subset of the features of its sister app in China, 抖音 (“Douyin”), which is more social. Instead of a dedicated notifications tab, Douyin has a news tab which is primarily a messaging inbox. Since videos in Douyin can be sorted by city, the introduction of messaging allows the platform to facilitate friendships in real life. Furthermore, a larger focus on livestreaming and ecommerce give creators financial incentives to broadcast and create great content through these mechanisms. So, it will be interesting to see how TikTok evolves on the social front.

TikTok is the first mainstream consumer app where artificial intelligence IS the product. It’s representative of a broader shift.

…It all comes down to AI

Because TikTok’s success hinges on the strength of its algorithms — it is not easy to otherwise curate hundreds of unique videos everyday for each user — the format of short UGC video, viewed on mobile, paired with AI personalized recommendations has created a sticky platform with global appeal. In China, daily use time is 31 minutes (over 120 videos); in the U.S., monthly usage in October 2018 was 6.8 hours.

More broadly, I believe TikTok’s rise signals a new era of AI consumer apps. Not only can the learnings from TikTok be applied to a vast range of consumer behavior — reading news, listening to music, making purchases — but also Chinese entrepreneurs are already applying learnings to new categories such as dating, learning, and recruiting. In the same way WeChat ushered in the era of “super apps“, TikTok’s parent company Bytedance is ushering in the era of AI consumer apps. But there’s more, beyond TikTok…

AI consumer app example #2: Soul, bringing back anonymity

In an ideal world, building relationships would be based on complementary personalities, interests, and values — and Soul, a more recently popular app in China, uses AI and anonymity as the cornerstones for facilitating such relationships. Popular use cases range from wanting to just talk or vent anonymously, to finding new friends and soulmates. As of May 2018, Soul had over 3.5 million MAUs.

When users join Soul, they answer a six-question quiz (with 50 optional further questions if so desired) with binary answers that serve as the baseline for the app’s AI matching algorithms:

- Would you prefer to be seen as firm or tenderhearted?

- Are you better at helping close friends understand emotions or making logical decisions?

- What is more important in conversations: maintaining interpersonal connections or reaching agreements?

- In your work, which do you display more: enthusiasm or perfectionism?

- Do you often forget trivial chores?

- Which better describes your life goal: seizing life’s opportunities to capture its brilliance or searching for the meaning and essence of life?

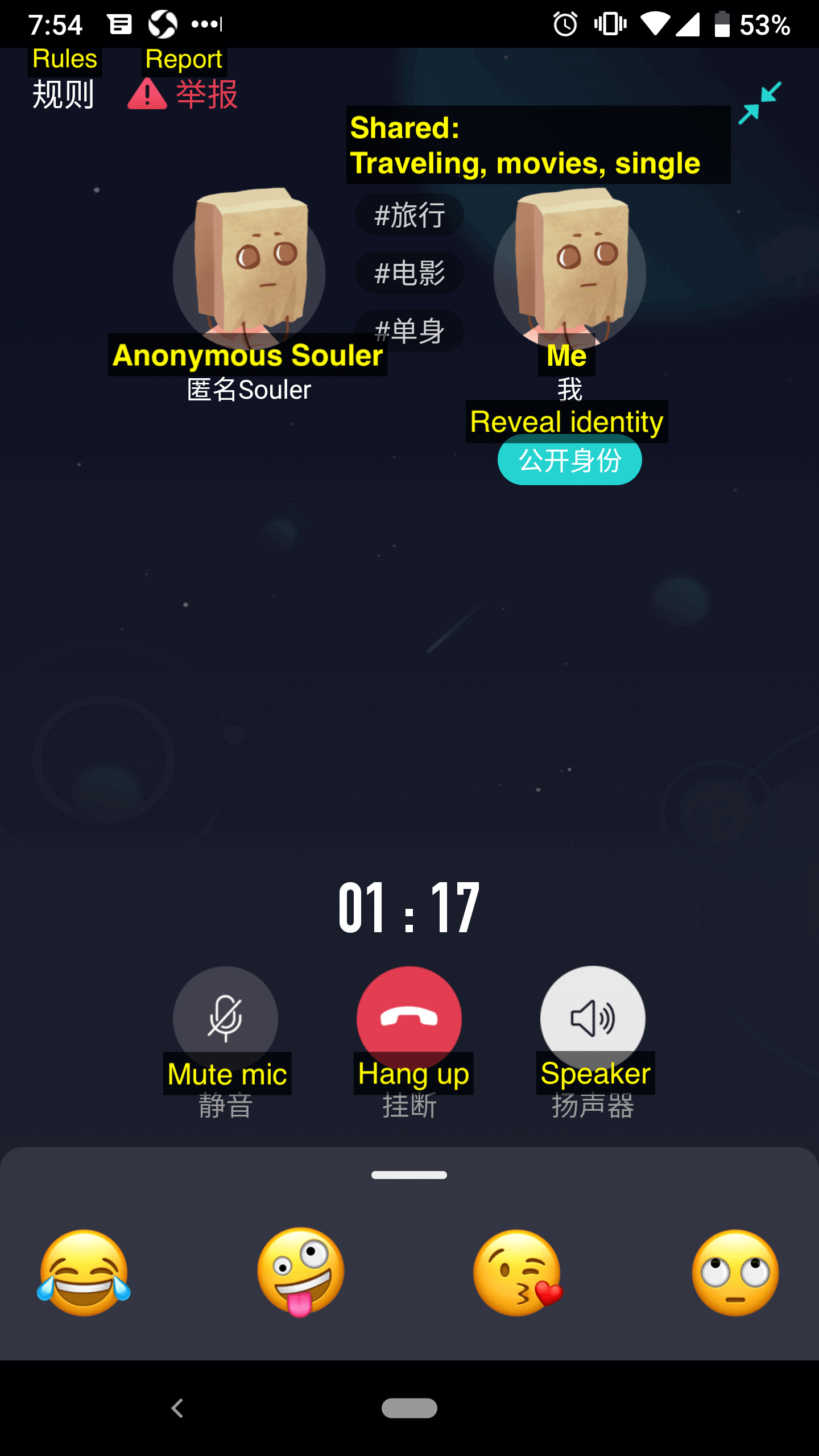

Once the quiz is completed, users are eligible to be matched and can choose to have a conversation with strangers via text or audio. Most importantly: no real names, photos, or even quiz answers are revealed — users actually have the option of changing their voice, and there’s even a paper bag that conceals the avatar heads! AI drives the matching algorithm based on at least an 85% compatibility score.

Chats begin immediately when two strangers are paired, and users are given suggestions on what to talk about. Either user can end the chat at any time, and after three minutes, both parties must decide whether or not to reveal their usernames to continue the conversation. The platform has full visibility into when and why the conversation fell apart.

It’s as if a dating service got to listen in on your first date and use that information to find your next match.

By using AI to generate matches, Soul also gives users more confidence that their matches are not random and have a decent chance of success. In other words, AI helps restore trust in anonymous chats. Soul’s approach has other benefits as well; for instance, by stripping the experience of video and relying only on voice and messaging, interactions are not based on physical attraction, so rejection is taken less personally. (After all, maybe the platform just made a bad match!)

The app draws parallels to Chatroulette, of which one in eight matches has questionable content. But on a platform molded with AI, “questionable” users are either weeded out or only matched with other users that they’re likely to still have a shot with. Soul’s popularity demonstrates how an AI approach can give new life to an old consumer app idea. How many other failed business models could be revisited with an AI strategy today?

AI consumer app example #3: LingoChamp, providing affordable education

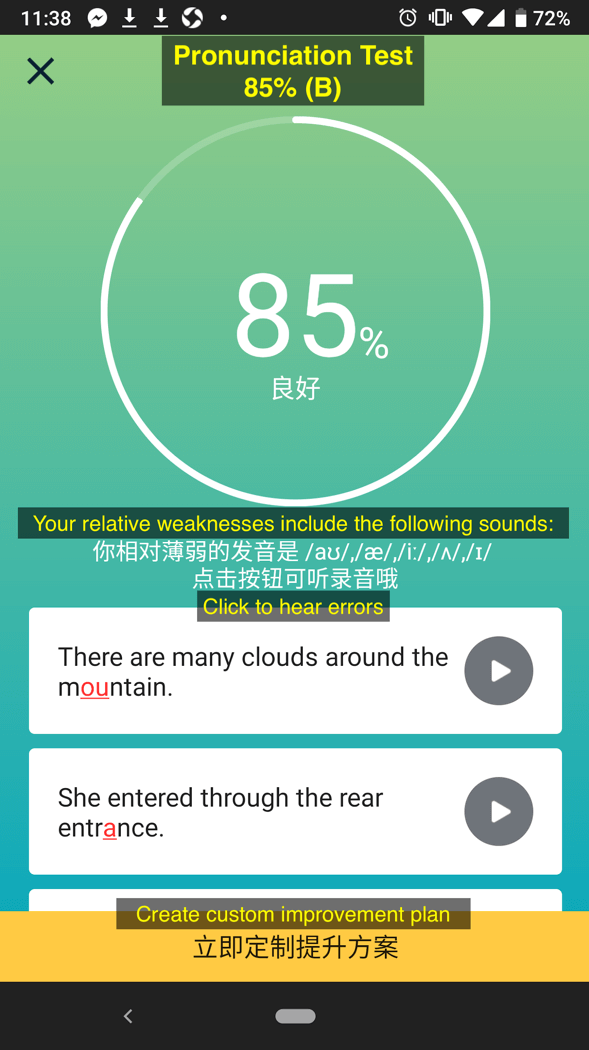

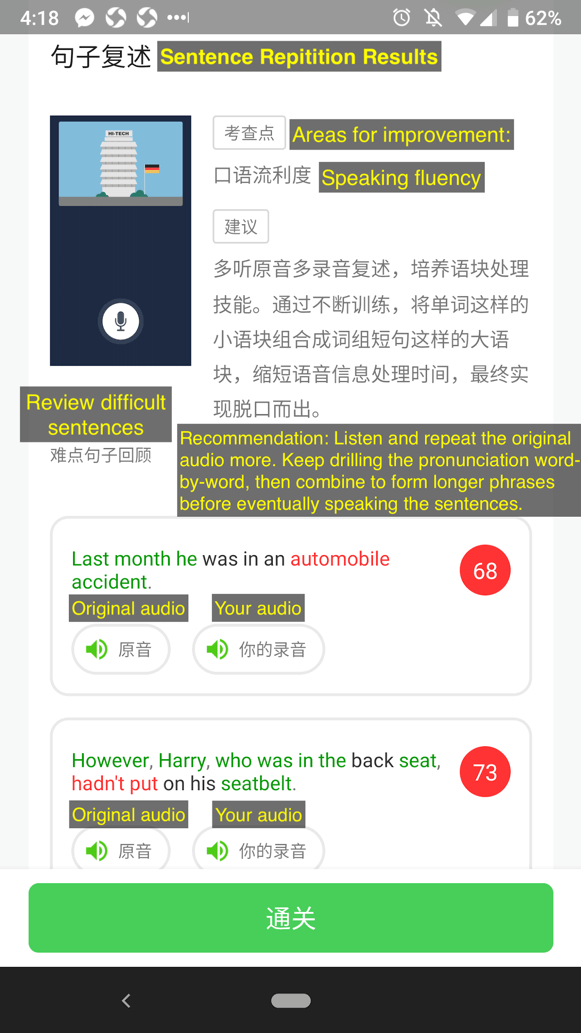

Imagine an English tutor that can give you feedback on pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and overall fluency — that kind of 1:1 tutor could easily cost upwards of $40/hour in first-tier Chinese cities. But LingoChamp is an AI English tutoring app that charges users $14/month for unlimited access to tests, courses, and personalized curriculum. In Q3 2018, the app had 97 million total users with over 870,000 paying customers (158% growth YOY) — the equivalent of $26.3 million in net revenue and 73.4% gross margins.

Users start by selecting level of schooling; purpose for using the app (international business, travel, karaoke, watching movies, IELTS exam, study abroad, etc.); and then they complete an assessment exam. Once the users’ level is determined, they can take bite-sized courses on how to say hi to foreigners or how to ask for employee benefits, or simply reading a children’s storybook. The platform gives users audio playback of any mistakes as well as smart analysis and suggestions for improvement.

Users start by selecting level of schooling; purpose for using the app (international business, travel, karaoke, watching movies, IELTS exam, study abroad, etc.); and then they complete an assessment exam. Once the users’ level is determined, they can take bite-sized courses on how to say hi to foreigners or how to ask for employee benefits, or simply reading a children’s storybook. The platform gives users audio playback of any mistakes as well as smart analysis and suggestions for improvement.

LingoChamp therefore has the world’s largest dedicated database (as of Q2 2018) of English spoken by Chinese at various proficiency levels — it has trained its AI model with over 1.3 billion minutes of conversation and 17.5 billion sentences. Lingochamp then uses this data to predict user success and tailor questions to be challenging, but not discouraging. Finally, LingoChamp’s parent company LAIX also offers a free International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam app that uses their AI engine to give advanced feedback for practice exams.

All this data, combined with AI, provides the company’s moat against competitors. According to iResearch, China’s AI-powered online education market reached approximately $568 million in 2017 and is expected to surpass $26 billion in 2022 overall. But the bigger picture here is about AI enabling scale and access: In a country where there’s a huge deficit of English teachers (70% of primary and secondary schools in Yunnan province alone lack English teachers), the app is not just making English learning orders of magnitude cheaper, but truly more accessible to all. As founder Yi Wang observes, “The variable cost is so low that it’s negligible. This is a whole new model of really pushing the boundary of human learning forward.”

All this data, combined with AI, provides the company’s moat against competitors. According to iResearch, China’s AI-powered online education market reached approximately $568 million in 2017 and is expected to surpass $26 billion in 2022 overall. But the bigger picture here is about AI enabling scale and access: In a country where there’s a huge deficit of English teachers (70% of primary and secondary schools in Yunnan province alone lack English teachers), the app is not just making English learning orders of magnitude cheaper, but truly more accessible to all. As founder Yi Wang observes, “The variable cost is so low that it’s negligible. This is a whole new model of really pushing the boundary of human learning forward.”

Imagine how such AI knowledge sharing could be extended beyond English tutoring. As such, AI is a cost-effective solution to scaling education to make it both accessible and inclusive.

How many other failed business models could be revisited with an AI strategy today?

* * *

These are just three examples — for short video, anonymous chat, and English learning — of AI consumer apps. Other examples include Boss Zhipin and VIP Peilian: the former uses AI to match job applicants and employers, optimizing its recommendations to increase the chances of an applicant landing a job; and the latter uses AI for music education, evaluating how each song is played based on pitch and rhythm. Because both apps use an AI-driven approach, the app (in the case of Boss Zhipin) can recommend a long tail of potential employers, and the app can also (in the case of VIP Peilian) be much cheaper — a fraction of the cost of an in-person instructor.

What all these apps show is the earliest innings of a new wave of consumer startups where AI is the product. Everyone talks about TikTok — and Toutiao, China’s leading news app that uses AI to deliver a personalized feed to each of its users (both created by the same company) — but the question we should ask ourselves is not whether these apps stay at the top, but what other problems for consumer behavior can AI solve?

In his recent book AI Superpowers, former NLP researcher/ technologist Kai-Fu Lee argues that “Much of the difficult but abstract work of AI research has been done, and it’s now time for entrepreneurs to roll up their sleeves and get down to the dirty work of turning algorithms into sustainable businesses.” But as I’ve outlined in this post, the implementation phase has already begun. So what’s coming next in this new era of Consumer AI apps?

acknowledgements: with thanks to Avery Segal for his research and other help on this post