Your company’s compensation philosophy, process, and bands determine how most of your hires are compensated. Executive hires, however, are a little different. You’re often dealing with heated competition for a small pool of talent. Competitive compensation packages generally need to be more bespoke, and the challenge is putting together a competitive offer while also balancing the cost and consistency with existing leadership team compensation.

In this post, we cover some of the most important topics for late-stage companies putting together an executive compensation package, including:

- How to think about the mix of base, bonus, and equity

- Best practices for benchmarking

- Selling a candidate on the value of equity

- What you’ll need to disclose about executive compensation

- How to make the offer

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Compensation elements

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In the best hiring processes, compensation is part of the discussion between the candidate and executive recruiter from the very beginning, so that when you decide to make someone an offer, you know their expectations. Generally, it’s best to keep offer letters simple and focused on base salary, cash bonuses, equity or stock options, and change in control (CIC), which includes severance. If you offer other incentives or programs, you’ll typically discuss those elements separately.

As a note, while the board won’t usually need to approve the compensation package, they will typically approve the equity grant. It’s good practice to have your board’s compensation committee or the board members involved in the interview process advise on the comp package.

When putting together the offer, base salary, cash bonuses, and equity, each serves as a different incentive lever. A good offer uses those levers to get the executive to come on board and to align them to what you need them to do:

- Base salary establishes guaranteed compensation and fixed income. Growth companies tend to be in a stronger cash position than early-stage companies, so base salaries are generally higher. For the best executives, base salary is unlikely to be the reason they take the job, but it can be the reason they don’t.

- Bonuses incentivize short-term measurable goals (usually 12 months or less). They tend to become more common as a company matures into the later stages and try to balance their long-term incentives (generally equity) with short-term incentives. Sales teams will almost always have some sort of bonus structure as part of compensation, but not all companies have or want to run a bonus plan for non-sales roles. If you don’t already have a bonus plan in place, a new executive hire isn’t the time to implement one.

- Equity aligns an executive with your long-term vision and success. While competitive offers almost always include great base salaries, your vision—as represented by your equity offer—is what brings executives to the table. While a candidate may have a base salary range, a good candidate could likely get multiple offers in that range. The reason they say yes to your offer is more likely to come down to how much they believe in your vision, their ability to meaningfully contribute to it, and the value of their equity when they do.

- Change in control clauses go into effect if your company undergoes a significant change in ownership, such as a merger, acquisition, or sale. By ensuring that executives are financially secure in the event of a change in control that could affect their employment status, CIC clauses align executives with the best interests of the company. The specifics of these clauses vary widely, but executives typically negotiate severance, accelerated equity vesting, and double-trigger requirements. Overly generous CIC clauses can often lead to accusations of corporate excess, so as a CEO, it’s critical that you balance whatever provisions you offer against the interests of your company.

As you determine your mix of incentives, there are a few things to keep in mind.

What is the role?

Different executive roles tend to have different mixes of compensation, and typically, you’ll want that mix to match the time horizon to the role. Sales leaders, for instance, focus quarterly and thus have variable cash incentives in the form of a bonus or commission that may contribute up to 50% of on-target earnings (OTE). You want a sales executive motivated to hit quarterly goals and keep your company on track in the short-term. A product executive, on the other hand, works on a longer time horizon when building the product roadmap—often thinking 2–3 years out—so it makes more sense for their compensation to be weighted more toward base salary and equity than toward bonuses.

Strike the right balance with CIC clauses

CIC clauses ensure that executives are financially taken care of if the ownership of the company changes. While not all venture-backed companies have adopted these provisions, it’s important for CEOs and their teams to understand how they work for 2 main reasons: 1) many executives negotiate these clauses because they provide job “insurance” in the event of any strategic or organizational shifts caused by a change in the company’s control, and 2) CIC clauses can impact the price of a merger or acquisition, or derail it altogether, if the management team isn’t aligned on their roles post-acquisition.

As a CEO, it’s your responsibility to ensure that CIC clauses center the company’s best interests while also aligning your executive bench with the longer-term goals of the company. Because these clauses can be complex and require careful negotiation, we recommend that CEOs seek legal counsel when drafting these provisions to fully understand how the provisions included in CIC clauses might impact the business in the event of a change in control.

CIC clauses can vary widely from hire to hire, but they generally include:

- Severance clause: this clause generally provides for special severance benefits in the event of a change of control. This could include a lump-sum payment, accelerated vesting of unvested stock options, continued health benefits, or other provisions.

- “Triggering” event clause: this clause specifies what events qualify as a change in control. Generally, a triggering event occurs when 50%+ of the company’s voting power is transferred as part of an acquisition, merger, sale, or other disposition of the company’s assets.

- “Double trigger” clause: in some cases, the change of control clause might include a “double trigger” provision, which stipulates that 2 events must occur for certain benefits, like, severance, to be granted to an employee. This second trigger typically involves termination of employment under specific conditions—sometimes referred to as “good reason” (more on this below)—involuntary termination, or a significant change in the employee’s role.

- “Good reason” clause: in the event that an executive’s role changes significantly after a change in control, “good reason” clauses allow them to trigger their CIC agreement without being formally terminated by the company. “Good reason” clauses generally include significant changes to an employee’s compensation, role, or work location, specifically:

- Protection against a change in role or duties, which ensures that an executive’s role stays relatively the same after a change in control

- Protection against material change, which prevents the company from adjusting the executive’s salary lower than 10%

- Protection against relocation more than 30 miles from their current location that materially increases the commute time from their residence

Creating incentives, not disincentives, with bonuses

When it comes to bonuses, it’s important to understand what incentives and disincentives a bonus creates, both for the executive and their team, when including it in a compensation package. You should expect that an executive and their team will optimize for whatever you’re measuring—the bigger the potential bonus, the more they will optimize. For instance, if your company-level goal is a certain topline revenue number, and you tie a bonus to hitting pipeline targets in the next 6 months, your teams will likely be hyperfocused on pipeline generation during that time. If you don’t have a clear process for inspecting and qualifying the pipeline, you may be creating a perverse incentive to generate poorly qualified leads in order to make the number.

Another failure mode with a bonus program is paying out when an executive or team doesn’t hit a goal. Even if the team worked very hard or came close to hitting their targets, by paying a bonus even though the measure wasn’t hit, you’ve created an expectation that future bonuses will be paid, regardless of performance. At this point, your team may come to expect bonuses, which may no longer work as short-term incentive levers. Be very clear up front about what level of performance is necessary for an executive to receive a bonus.

If you want to avoid all-or-nothing payouts, you can set thresholds at which someone will get 50% or 75% of their bonus. You can also use a structure like this to incentivize continued performance once the goal is met, so that as someone hits a target, the bonus outcome levers up. If you do this, you’ll want a clear perspective on the financial impact if an executive blows past the initial target. For instance, if you set a sales target of $1.5M and then see increased demand for your product, so that you’re on track to 2x your targets, it could become too costly to the company to have a straight line on bonus pay. It’s better to set a maximum payment and then use discretion about whether to exceed it.

Benchmarks ≠ compensation philosophy

Competitive market benchmarks are among the key inputs to putting together an offer. While useful, benchmarks alone are not enough to determine an executive’s compensation. Rather than a blanket approach of “paying in the 75th percentile,” we recommend having a consistent philosophy on how you position executives against the market. When you need to vary from the baseline, that philosophy is there as a sense-check for your rationale. For instance, if you want to pay an executive at the 90th percentile for their base salary, that might mean paying someone an extra $150,000 and giving away another half-point of equity, which could be the cost of an early career engineer. Is that where you want to invest your cash and equity? The compensation for that hire may become visible once you’re public, so make sure you can explain to everyone why you pay them what you do.

The smaller or more competitive the talent pool and the more critical your need, the more likely you’ll have to pay a higher benchmark. For instance, a company who wants to hire a chief human resources officer (CHRO) from a public company to lead a shift to a remote-first workplace and ramp up the recruiting process may find the pool of available talent is small given the high level of burnout with HR leaders. To compete for talent, you may need to pay in the 90th percentile. On the other hand, if you’re a company with a single SaaS app product looking to hire a VP of engineering, you may pull from a larger pool of qualified candidates and be able to get the caliber of leader you want by paying in the 50th percentile.

When benchmarking compensation, we recommend benchmarking the overall size of the compensation package, as well as the specific elements that make up that package, against your competitors for talent, not the whole market. For earlier-stage companies, capital raised will typically be the best way to identify similarly sized companies. In the later stages, as the company starts to generate revenue and self-fund cash compensation, we recommend using revenue to scope market data. It’s also important to consider your industry. A company in a more capital intensive industry, such as a biotech company working on drug discovery, tends to raise more capital than similarly sized companies in traditional tech. In these cases, it can be helpful to identify companies with headcounts similar to yours. If you’re looking to recruit from a public company, you’ll also want to understand benchmarks for relevant public companies.

When it comes to actually making the offer (which we discuss in more detail in the Making the offer section), we generally see companies go in at 90%–95% of their maximum on cash and 85%–90% of their maximum on equity and use the promise of equity to move the meter.

We’ve generally seen high-quality benchmarking from Pave, Carta, and Radford. It’s also important to benchmark your company’s compensation against industry standards, for which there are a range of tools available, for industries ranging from biotech to gaming.

Titles

Finally, a note on titles. There’s been a lot of discussion around title inflation in recent years, and we’ve written about some of these perspectives. Some leaders think that when you inflate titles—especially in the early stages—you’ll likely end up paying for it in the later stages. For instance, if you give your sales leader a chief revenue officer (CRO) title and a corresponding compensation package when you have only 70 employees and a handful of sales people, and later you need to bring in a more experienced CRO, the original leader will need to be leveled or perhaps leave the company. This can be particularly difficult if your original leader has been with the company since the early days and is, for instance, a particularly good steward of your company culture or especially talented at a particular part of sales.

Others, however, find that offering a high-level title can be the key to closing a critical candidate who can jump in, roll up their sleeves, and get your company to where it needs to go. Titles don’t correlate to more equity or necessarily more compensation, and they can be an easy way to get a leg up against the competition in the hiring process. You might need to level or let that executive go in 2 or 3 years, but this isn’t an uncommon position to be in.

So which approach is better? It depends on your business and how well you can attract the talent you need. In either case, however, it’s critical to run a rigorous hiring and compensation practice. As we emphasize in The Hiring Process, if you can’t define it, you shouldn’t hire for it. The best way to get the leader you need is to define the role clearly and then work with your HR leader to determine the title and reporting structure that make sense, given the scope of responsibilities. From there, you’ll be able to identify executives in similar roles and establish a compensation range for the position up front.

Structuring equity

Equity is the most complex compensation element, and often the most consequential, when hiring executives. When structuring equity, the most common practices for vehicle type, vesting schedule and triggers, and the post-termination exercise period are:

Vehicle type. When it comes to giving an executive equity, companies typically use three vehicles: incentive stock options (ISOs), nonqualified stock options (NSOs), and restricted stock units (RSUs). ISOs and NSOs give the executive the option to purchase stock at a set price (known as the exercise price) once they’ve met predetermined vesting requirements. When you exercise stock options, the difference between the option’s strike price and the fair market value of the shares at the time of exercise is considered taxable income. For options, ISOs are preferable to NSOs, because ISOs are generally taxed only when an individual sells their shares, whereas NSOs are taxed when the executive exercises the option. The IRS limits how many ISOs you can grant an individual, and once that limit is reached, ISOs convert to NSOs.

Unlike stock options, which have a strike price (the price at which the option can be exercised), RSUs are granted at no cost to the employee in a fixed number of units that will convert into company shares upon vesting, which is usually based on 2 triggers: time and a liquidity event (IPO or sale). RSUs are designed this way so that the executive does not have a tax obligation without the ability to use their liquid stock to cover the tax obligation.

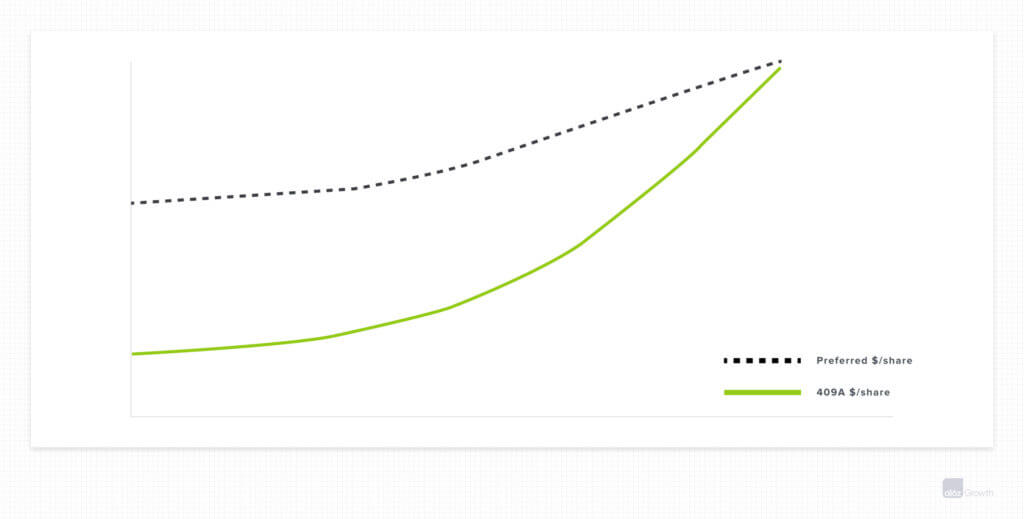

In the early stages, a company will generally offer stock options rather than RSUs, because stock option holders will benefit from a gap between their stocks’ preferred value (what investors typically invest at) and the 409A value that determines the strike price on options. Granting stock options rather than RSUs takes advantage of this “cheap stock” gap. Over time, if the company’s 409A valuation increases, this gap diminishes and the strike price on options increases.

Since an executive only realizes the upside on options if the eventual value of the company’s stock goes above the strike price, a higher strike price constrains that potential upside. Additionally, the volatility and market dynamics following an IPO could put more recently granted stock options on the open market with a strike price higher than the stocks’ trading price. RSUs don’t necessarily hedge against market volatility directly, but they are a more stable form of equity. RSUs are granted in a fixed number of units and don’t have a strike price. While the value of the underlying shares could still be affected by market volatility, the lack of a strike price means that executives don’t need to worry about their RSUs going underwater (i.e., having a strike price higher than the market price). As a result, in the later stages, companies transition executives from options to a mix of options and RSUs—for example 75% options (NSOs and ISOs) and 25% RSUs.

When a company chooses to shift from options to RSUs, it’s important to determine an appropriate conversion ratio and adjust grant guidelines for executives accordingly. Stock options require that you pay a strike price, but with RSUs, you’re just issued the full share outright, with no obligation to pay a strike price. Typically, 1 RSU replaces 2–4 stock options. When calculating the exact conversion rate, consideration should be given to the intrinsic value of current stock (preferred value less 409A value), the lack of downside risk for RSUs with the lower potential upside based on the smaller number of overall RSUs granted (relative to stock options), and the impact on your share pool reserves.

Typically, we offer companies the guidelines below for when they should consider a move to RSUs:

- Actual company value exceeds $1B, supported by significant revenue growth

- Will reach a head count of 700+ employees within the next 6 months

- Clear path to liquidity in 18–24 months

- Nominal gap between preferred value and 409A value

- If they have dilution concerns and high equity burn, and/or an unusually high 409A relative to preferred value, a company may find it makes sense for them to transition to RSUs, even if they don’t meet the criteria above

Vesting schedule and triggers. The vesting schedule determines when an executive can exercise options. Typically, ISOs and NSOs vest incrementally over 4 years, contingent on continued employment. Vesting is usually incremental (known as a cliff), with the most common structure being a 25% cliff after the first year and monthly thereafter. In other words, after a year of employment, the executive could exercise 25% of their options.

In the case of RSUs, vesting occurs and stock is granted automatically once certain conditions are met. Vesting conditions can be either single- or double-trigger. We strongly recommend setting up double-trigger vesting, with the primary trigger being time-based and tied to continued employment, and the secondary trigger usually related to a liquidity event (e.g., an IPO, acquisition). If RSUs carry only a single trigger of time-based vesting, employees who vest prior to a liquidity event will have taxable income without the ability to easily sell shares to cover their tax liability.

Refresh and promotion grants. You don’t want to end up in a position where an executive’s equity is predominantly vested. Generally, executives with more than 2 years of tenure who are performing in their role should be eligible for a refresh grant, or a grant that layers on additional options.

Refresh grants for executives tend to be around 0.25x, or even as high as 0.3x, of the new hire grant. For comparison, the average employee will typically be refreshed at 0.10x–0.15x (for top performers 0.15x–0.20x). Executive refresh grants are generally greater than those of broad-based employees because employees are still growing into their roles. For a growth-stage executive, the expectation is that if they’re still there, they’re performing.

Post-termination exercise. For RSUs, an executive will have the right to any vested shares with no taxable income recognized until a liquidity event (assuming RSUs require a double-trigger vesting). For ISOs and NSOs, you may choose to extend the post-termination exercise window beyond the standard 90 days. If you do take this approach, a best practice is to use an executive’s years of service to determine how long after employment ends an executive has the ability to exercise options (i.e., a post-termination exercise window). The most common structure provides an incremental year of post-termination exercise after 2 years of service. Companies that extend the post-termination exercise window out over years run the risk of carrying “dead equity,” putting additional pressure on dilution, and so, many companies cap the window at 2–3 years.

Selling the value of equity

Because equity and stock options are based on an uncertain future, equity is only as valuable as a candidate believes it is. If a candidate believes in your vision and your ability to execute it, they believe in the value of their equity. Since selling the value of equity to a candidate is really selling your vision, it’s a conversation best handled by you, the CEO.

If you’re recruiting an executive, especially one from a public company, and find yourself debating the current value of your equity, you’re having the wrong conversation. Your candidate is chasing a dollar amount on the company’s current value, but unlike shares in a public company where most of the value has been realized, the real value of your equity is the future upside if you succeed.

Instead, the conversation you want to have focuses on the overarching goal of your company and how it’s structured to hit those goals. You want to lay out your vision and the key milestones you’ll have to hit to get there (i.e., revenue, key customers, product adoption, efficacy) and connect those milestones to your candidate’s role. If you provide a clear understanding of how your company is set up to become a $10B company, and your candidate believes in your ability to get there and their ability to help you get there, the conversation isn’t about the current value of their equity, but rather their ability to realize that value.

Once the candidate is sold on the value of your vision, then you can dig into the specific scenarios and potential value of the equity. Here, it’s helpful to walk through the most recent fundraise and valuation, why investors found it compelling to invest in the company, different exit scenarios, what the company would need to achieve for each of those scenarios, and the resulting value of the executive’s equity compensation. When highlighting specific outcomes, the more you can explain the potential for the executive to impact the company’s future outcomes, the more compelling the equity becomes.

If the market has changed recently and you’ve had to adjust your 409A valuation, we typically suggest you explain to candidates that valuations reflect more about the market than about company performance, then focus on selling your ability to create value in the long term.

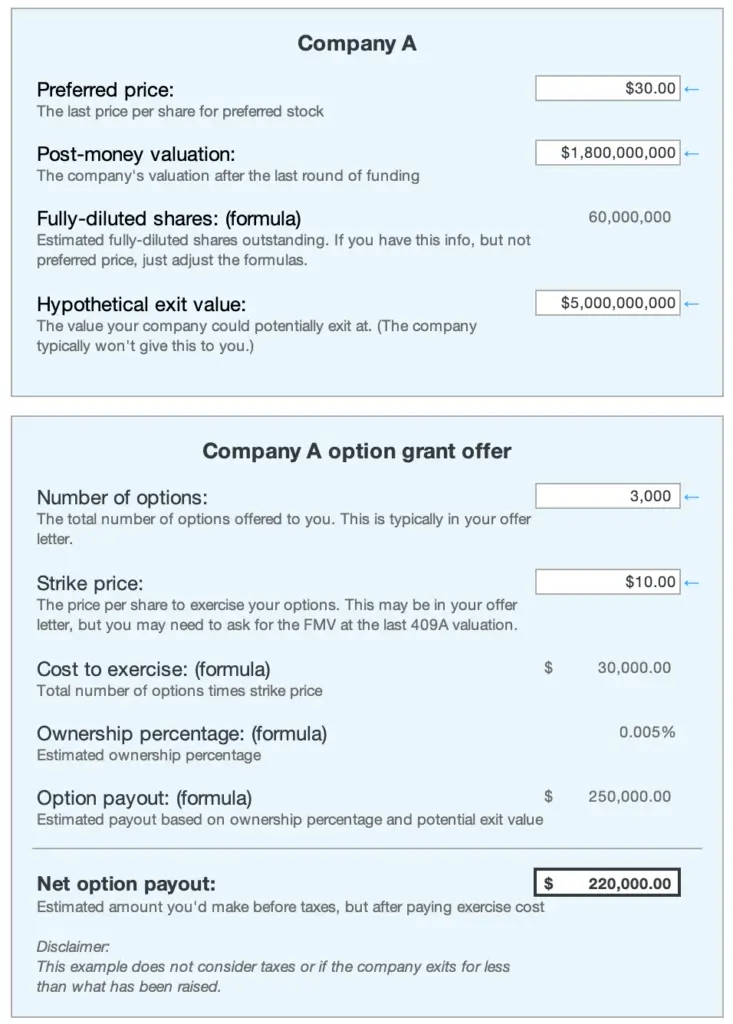

Finally, while the strike price matters, candidates sometimes get hung up on differences that won’t have as material an impact as they expect. Models and visualization tools (we give one below, from Carta, for calculating the value of stock options) can help present different outcomes and the impact on stock options.

In these instances, it can help to play out the math on different strike prices to highlight that the value you create matters far more than a few dollars in the strike price. The bigger the exit, the more valuable the options become and the less relevant the strike price. For instance, let’s compare a set of 10K options granted with a strike price of $1 to 10K options granted at a strike price of $3:

- If a liquidity event occurs at $20 a share, the $1 options are worth $190K, while the $3 options are worth $170K.

- If a liquidity event occurs at $50 a share, the $1 options are worth $490K, while the $3 options are worth $470K.

IPO: disclosures & dilution

For late-stage private companies approaching a potential IPO, executive compensation becomes particularly important for 2 reasons: the need to disclose executive compensation and the need to transition from stock options to RSUs to avoid overly diluting your existing equity.

Disclosures

A good rule for executive compensation is: if you don’t want it out there in the public, don’t do it.

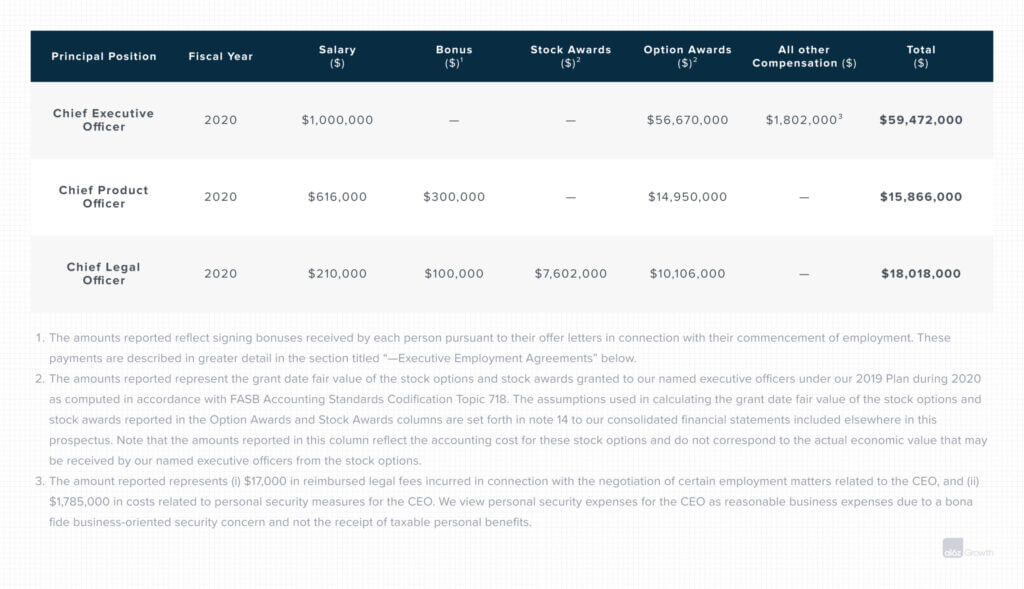

As you approach a potential IPO, you’ll be required to disclose some of your executive compensation on registration statements, most typically an S-1. While the specific requirements vary with the size of the company, you should be prepared to disclose the compensation of your CEO, CFO, and next 2–3 highest-paid executives. (We include a sample compensation summary table below.)

To prepare for these disclosures, we’d recommend setting up a board compensation committee and partnering with an independent third-party consulting firm to help prepare for the needed disclosures about 1–2 years before an IPO. These disclosures are often broad and go beyond just base salary, bonus, and equity to capture anything and everything—club memberships, relocation assistance, travel reimbursements, legal fees, security costs—that an executive receives from the company, even if you don’t consider it part of the executive’s compensation package.

You’ll usually need to make these disclosures for the current year, as well as a year or 2 prior. Once you’re public, you’ll be required to make those disclosures going forward. If you think there’s a compelling business reason for a particular executive expense, have a clear compensation policy that you can use to explain it on the registration statements.

Dilution

When you’re about 2 years from an IPO, equity dilution can become a major gating factor for executive talent, and you’ll want to manage your options pool and equity burn rate carefully. Some companies will set an options pool at 5% and top it up at the end of year, so they can negotiate with talent without having to manage additional shareholder negotiations.

Additionally, around 18 months pre-IPO, most companies transition from stock options to RSUs. The company’s HR team, in collaboration with the finance, legal, and board compensation committee, will provide recommended grant guidelines based on market competitive grants, as well as a proposed conversion ratio from stock options to RSUs (typically 1 RSU for 2–4 stock options). As a best practice, you’d regularly provide your board with a grant budget and track budgeted versus actual grants in conjunction with the board’s standard grant-approval process.

Making the offer

If you’ve run an effective hiring process, by the time you’re ready to make a candidate an offer, both you and the candidate should be aligned on expectations for salary, equity, and bonus. When it comes to actually making the offer, we typically open the conversation by asking, “Specific details of the offer aside, are you ready to say yes? Are you clear on and excited about the outcomes you need to drive, what you’ll need to do, who you’ll need to work with, and what you need to be successful?” Once we know the candidate is ready to say yes, we walk them through the offer verbally and follow up by sending the offer letter.

If you’re extending an offer to a candidate who works for a company known for aggressive counteroffers, you’ll want to help the executive prepare to resign and avoid a counteroffer. When you’re ready to make an offer, discuss the possibility of a counteroffer and ask the candidate: 1) What’s their motivation for joining your company? and, 2) Is there anything their current employer could offer that would convince them to stay?

If you believe the candidate sincerely wants to join your company, and no new role or amount of money would make them stay at their current employer, then make the most compelling offer possible. Once you agree on a compensation package, hold your ground and stay close with the candidate to support them in resigning effectively and onboarding to your company.

Relocation assistance

If you have an executive candidate who will need to relocate, we typically recommend that you have a strategy for relocation, set expectations early in the process, and then include a relocation package with their offer. As part of the early conversations around relocation, try to assess whether they’re planning to move for the job or were already planning to move. If they were moving anyway, you might not need to offer as substantial a relocation package.

Generally, a company can provide 3 different types of relocation policies:

-

- You provide a lump sum. By offering a lump sum of money, you’re telling the executive to “do what they wish” with the money. They might end up pocketing some of the money if they’re able to move under budget. Either way, it’s an easy hands-off approach that usually satisfies both parties.

- You reimburse the executive for relocation costs. It’s important to set a limit on the total amount of the move, which could otherwise quickly get out of control. This option also requires the executive to retain all receipts from the move, which is more work for them. It also requires a dedicated person at the company to monitor the move and expenses. If you’re concerned about offering a lump sum, this might be the next-best option for your company.

- You hire a third-party relocation firm to handle all the details of the move. Third-party relocation is an outsourcing of all move logistics, which might even include covering the costs involved in selling a current home (see below section on suggested expenses). This solution is recommended when: a) The company has the time and money to afford this option, and b) The executive is a critical hire to the company, and you need to make everything as seamless as possible for them.

We typically recommend the relocation policy cover:

- The cost of moving household goods and personal effects, including 2–3 months of storage

- The cost of traveling (including lodging), limited to 2–3 trips

- The cost of moving household goods and personal effects to and from storage—limited to 2–3 months

We recommend it not include:

- Any part of the purchase price of a new home

- Expenses of buying or selling a home (including closing costs, mortgage fees, and points)

- Expenses of entering into or breaking a lease

- A loss on the sale of a home

- Mortgage penalties

When setting a budget for relocation packages, keep in mind that much of the time, the executive will come back to you asking for $2K–$5K more than you originally offered, due to unforeseen costs toward the end of their move. In the case of a C-level executive hire, we find third-party relocation is often the best method, but be prepared that it will cost $50K–75K. If the executive will be commuting before relocating permanently, you should decide whether that will be part of the relocation budget or a separate expense line item as a part of regular business travel. Additionally, keep in mind that employees will be taxed on all reimbursements, and you may need to consider the after-tax benefit. When setting expectations, it’s important you communicate whether this is a gross, net, or after-tax amount.

When incorporating a relocation package into an offer, it’s a good idea to have a clawback clause in the offer letter for a prorated payback to the company if the executive leaves voluntarily or is terminated for cause, usually within the first 12–24 months. If someone is terminated without cause (such as layoffs), then the relocation money would not be required to be returned.

Next, let’s look at Scaling Your Technical Org, Scaling Your Go-to-Market Org, and Scaling Your Operational Org.

Further reading

We’ve drawn insights from some of our previously published content and other sources, listed below. In some instances, we’ve repurposed the most compelling or useful advice from a16z posts directly into this guide.

16 Things to Know about the 409A Valuation, Caroline Moon

The 409A valuation is what you use to grant your employees options on a tax-free basis. But what is it? Moon offers insight into the 409A, how it’s evolved, and the steps you can take to get started with your 409A valuation.

How Startup Options (and Ownership) Work, Scott Kupor

Do you understand your company’s employee option plan and, more importantly, can you communicate that to a potential new employee? Kupor breaks down the dynamic process of company ownership and what you need to know about the economics behind startup options and ownership.

A Better Job Offer Letter, The Carta Team

No candidate wants to parse legal jargon in your offer letter. These are some approaches to simplifying your offer letter, especially regarding equity and compensation, to give your candidate a clear understanding of the offer that’s on the table.

What Are Stock Options and How Do They Work?, Adam Lewis, Carta

Many companies offer stock options as part of their compensation package. Learn about different types of stock options, vesting schedules, and what happens to those options when an employee leaves the company.

Compensation Isn’t about Paying the Most, It’s about Being Consistent, a16z podcast with Thanh Nguyen and Shannon Schiltz

You can’t afford to take a short-term approach to compensation. You need to develop your philosophy early to create a consistent compensation method, and getting it right sooner can save you a lot of trouble later.

All Things Compensation, a16z podcast with Steve Cadigan, Greg Loehmann, Thanh Nguyen, and Shannon Schiltz

You need to be competitive in the hiring market, but your compensation has to be sustainable for your organization. Take a deep dive into all things compensation, from your philosophy to stock options, to gain clarity on what compensation actually means.

Guerilla Recruiting: Combatting the Counteroffer, Scott Weiss

Putting in the effort to recruit a candidate doesn’t stop at the offer letter. Here’s how to design a great hiring process, take control of the offer process, and put in the work to woo the candidate even after the offer is made.

Titles and Promotions, Ben Horowitz

Nearly every company makes mistakes regarding titles. Sooner or later, someone will be promoted to a role they’re not ready for, or employees will benchmark their performance against the worst performer at the level above them. Avoid these mistakes by defining your promotion process and title structure.

-

Brandon Cherry is a partner on the People Practices team focused on advising portfolio companies on compensation strategies.

- Follow

-

Phil Wong is a partner on the Legal and Compliance team focused on venture and growth investments and portfolio companies.

-

Caroline Horn is a partner on the Talent Network team, focused on executive talent.

- Follow